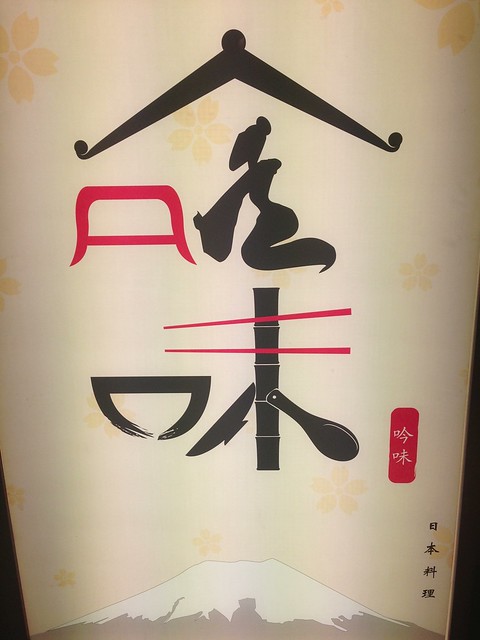

Chinese Character Picture Logo for “Yin Wei”

I definitely don’t like this logo as well as the 永久 logo, but this one is still noteworthy:

The Name

The name of the Japanese restaurant is 吟味. This is kind of a strange name to me; the only Chinese word I’m very familiar with that contains the character 吟 is 呻吟, which means “moan” or “groan.” It has numerous sound-related meanings, like “sing,” “chant,” and “recite.” 味, of course, means “flavor.”

In Japanese, I found an entry for 吟味 (ぎんみ) which means “testing; scrutiny; careful investigation.” I guess a name like that could be comforting in a country so beset with food safety issues?

The Pictures

I found it interesting how the mouth radical (口) is used in the same logo to form two very different pictures. The first one is of a table reminiscent of ancestral forms of the character 口, except upside down. The second one looks like a bowl, and although looking more modern, resembles a few of the other ancestral forms of the character 口 (and not upside down this time).

The right side of 吟 (the roof combined with the kneeling Japanese figure) to me really looks more like the character 令 than 今 in certain calligraphic styles.

Logos like this are interesting, but to me highlights an important point: Chinese characters are not pictures. They’re not even very much like pictures. If characters were really “like pictures,” this kind of logo wouldn’t work.

Certain Chinese characters and character components are historically pictographic in nature, yes, but you can see how even a basic pictographic element like the mouth radical (口) is actually very plastic. To me, what’s so fascinating about characters is not that they’re “like pictures,” but that they’re a ridiculously complex (and yet still viable) alternative symbolic system to alphabet-based writing systems.

I’ll write more on this subject later.

Would you say that, in addition to being ridiculously complex, Chinese characters are also more rigid and resistant to gradual natural change than alphabetic writing systems? It can be so easy to mispell English words, and obviously if error becomes common and persistent enough it will eventually become the new “correct” form. I feel like it’s more difficult to “mispell” a Chinese word however, since most words are condensed into a couple of characters, rather than a multitude of letters with often very different sounds depending which other letters they’re paired with.

I’d say no, certainly not. One reason is things like the logos John has featured in the last two posts and other creative reinterpretations of characters, like the old anti-drink driving sign that featured a 酒 done to look like a drunkly driven car with a red “no” line through it, even Daoist lucky charm characters. And besides, science has required the creation of new characters – look at the names of all the new elements that have been discovered over the last couple of centuries, for example. They had to be written somehow. Also, look at all the different calligraphy styles and how simplification was actually done – using common shorthand forms of characters was one of the ways of simplifying characters that was used. There are also many alternate versions of characters.

And “misspelling” Chinese is as easy as falling off a log. Just get the wrong strokes or miss a stroke or substitute a radical from a similar character or just plain write a similar-looking but wrong character.

I’m no expert on this topic, but it’s an interesting question, and I can offer a few opinions.

Characters were less resistant to change before the advent of the printed word, at which point “standard forms” and fonts had to be nailed down.

Nowadays, characters are encoded into the Unicode standard, and there are different forms specified in the standard for simplified Chinese characters, traditional Chinese characters, and Japanese kanji.

But what do you mean by “change”? Characters have traditionally defined readings and meanings. But those readings definitely change over time. And then you have the phenomenon of characters being used for new meanings (囧 being a good example).

So now the forms of the characters seem relatively stable (especially when young people these days are typing more than they’re writing by hand), but neither the readings nor the meanings are totally resistant to change.

Why is it so hard to type using the iPad? Is it the keyboard is just too big or too easy to touch somewhere else on the screen and wreak havoc on your post? Or maybe its “d”, all of the above.

Anyways, liked this post. But at the moment had my fill of China and Chinese. Momentarily

disillusioned by the shear impossible fealing associated with many things including learning to read, write, speak, understand Chinese, albeit these issuses are trivial when considered in the context of the bigger picture.

So, a Haerbin beer and some non Chinese music, combined with browsing sinosplice seems to be the dose for now.

Related/unrelated, John… for some reason looks like your pinyin plugin for the characters doesnt work when browsing via chrome/ipad.

Well I guess other than rambling I should say something real about this post… wait, I already did… I like it. Why? Characters are cool. Creative use of characters are even cooler.

I love music and art.

Chinese and charcters I feel have a bit of both built in. The logo above seems to me a fine display of how easy or should I say, compatible, Chinese characters are with art/creativity.

Not sure if qualifies as a mis spelling but rather an intentional “alternate use”… but today my teacher told me about using 杯具 vs. 悲剧. Why? As it was explained, 杯具 conveys the meaning, without the depressing feeling wrapped up in 悲剧.

Reminded me of how 去世 and so many other things are said instead of just saying 死亡,死了,等。

Nice post. Thanks John. Blogs are a labor of love and I haven’t felt much love for my own recently… you are a fine example for all wanna bloggers, including myself.

Another meaning of 吟味 in Japanese fits the characters and probably the intended meaning here better: “recite and savor [poetry]”. The earliest cite in the Nihon Kokugo Daijiten is a couplet by Li Qunyu 李群玉: “持甌黙吟味 揺膝空咨嗟”

Ah, thanks, that makes more sense.

Great to see a comment from you on here, after all this time. It’s always good to have an expert weighing in on something like this!

I’ve been reading for years! I just usually don’t know enough about China or Chinese to contribute anything worthwhile. But Japanese lexicology, that I can’t resist.

(Er, that is, their earliest cite is from Chinese, but they also have cites from Japanese after that. I don’t know how best to analyze the usage in Li Qunyu’s couplet, but the two-character combination was borrowed into Japanese as a single word.)