17

Apr 2014FluentU: a Producer of Original Videos for Learning Chinese (2)

As I mentioned in Part 1 of this review, FluentU is showing a lot of potential as a learning platform and a content producer. In this review I’ll look more closely at FluentU’s self-produced video series, and finish with an interview of content director Jason Schuurman (my ex-co-worker at ChinesePod).

Fluent-U’s Video Series

So, assuming you have a FluentU account, where do you find the FluentU-produced videos on the FluentU site? It’s not quite as obvious as you might think. They’re not aggressively recommended. But if you go into “Courses,” you’ll notice that some course names start with “FluentU.” Those are the ones FluentU has produced on their own. Unfortunately they’re not really grouped together for easy identification, so I went ahead and listed out all the ones I could find currently available on the FluentU website:

1. FluentU: A Good Morning (Newbie, 8 clips adding up to 2:07)

2. FluentU: Table for Two (Elementary, 7 clips adding up to 3:48)

3. FluentU: Making Friends and Drinking Coffee (Elementary, 12 clips adding up to 3:01)

4. FluentU: A Trip to the Supermarket (Elementary, 7 clips adding up to 4:50)

5. FluentU: Studying on Campus (Intermediate, 8 clips adding up to 4:58)

6. FluentU: An Evening Get-together (Intermediate, 8 clips adding up to 8:20)

7. FluentU: Dinner with a Friend (Intermediate, 9 clips adding up to 6:42)

8. FluentU: Shopping at the Clothing Store (Intermediate, 7 clips adding up to 6:34)

9. FluentU: A Basketball Afternoon (Intermediate, 8 clips adding up to 6:13)

10. FluentU: Going in for a Job Interview (Upper Intermediate, 9 clips adding up to 7:13)

So only 1 Newbie series, 3 Elementary, a whopping 5 Intermediate, and 1 Upper Intermediate. I was hoping for more video at the lower level, but at least I got to see what FluentU created across 4 levels.

One of the things I really like about these series is that although they’re broken up into short episodic clips, there’s also a “full” version that ends each series, putting all the clips together. This is great for review, and it also meant that I could easily watch each series without having to watch them one by one. (Watching a series on FluentU isn’t quite as easy as watching a playlist on YouTube.)

The video themselves are professionally made, using young, attractive actors. There’s a bit of a Taiwanese flavor to them all (unsurprising, since they were all shot in Taipei, I believe), which may upset the Beijing-centric putonghua police. I think it’s fine, though, the videos seem to be designed to be universally applicable to mainland China learners as well. I didn’t encounter any Taiwan-only vocabulary, pronunciation was pretty standard (although not perfect, by Beijing standards). There was also some Taiwan-style usage of sentence-final modal particles, like 哦, 啦, and 咯, but I didn’t find it too distracting.

At the lower levels, it’s clear that the creators slowed down the speech and added additional pauses for lower level learners. While this is nice, it has a funny effect, making some scenes feel quite awkward. You know those conversations where neither side is quite sure to say, and there are long awkward silences? There’s a lot of that feeling in some of the lower-level video series. Even within just the Elementary series, though, we quickly see the awkwardness in one series–FluentU: Making Friends and Drinking Coffee–fade to a much more natural rate of speech in FluentU: A Trip to the Supermarket. By Intermediate, the language is a lot more natural, while still being quite clear. I found the Upper Intermediate surprisingly accessible (read: not difficult), meaning it will be more useful for more learners, which is a good thing. (Other material marked “Upper Intermediate” on FluentU is usually quite a bit more challenging.)

I noticed that the writers also went to great pains to make the dialogs full of high-frequency words and phrases. While it’s usually easy to pick out words that aren’t useful in most videos or even standard textbooks, there really aren’t many at all in FluentU’s videos. In fact, the language is usually so simple and everyday that the videos don’t really through you any cureveballs at all. There aren’t “twist endings” like you frequently find in ChinesePod dialogs. One thing that keeps the videos interesting, though, is a pervasive flirtiness running through many of the male-female dialogs. You kind of expect the video to devolve into a “what’s your number?” or “we should hang out sometime,” but they stay innocent.

In fact, it’s the flirtiness, combined with an amusing awkwardness, that makes these original videos memorable. Probably my favorite example of this is the elementary video where the cute flirty waitress informs the young protagonist where the bathroom is, immediately followed up by a cutesy “don’t forget to wash your hands!” (Ha ha, wut??)

Then there’s also the very awkward pre-interview high-five (between strangers) in the Upper Intermediate job interview lesson:

(The girl and guy from that video are going to end up as co-workers, and if that sexual tension doesn’t later erupt in a sequel series, I really don’t know what the writers are trying to do here.)

Overall, I enjoyed the videos. Especially at the lower levels, they still feel like “studying,” but they’re very usable and easy on the eyes. I can see these being useful in the classroom, especially for college students.

Interview with FluentU’s Content Director, Jason Schuurman

Me: Although it’s a very different service, FluentU kind of reminds me of ChinesePod in that it offers a lot of material and tools, and it’s up to learners to put them together in the way that makes sense for them. Can you comment on how that might work at FluentU, and how different types of users use the service?

Jason: Yeah, we definitely provide a lot of freedom and flexibility. We feel this not only allows for a broader range of users to benefit from the site, but it also let’s our users take their learning into their own hands and not get bored with materials they weren’t interested in learning in the first place.

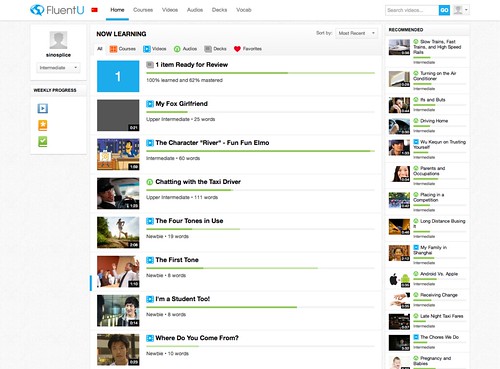

That being said, we still do provide structure for those who want it in the form of recommended content and more specifically, ‘courses’. Courses at FluentU are something like a playlist-meets-lesson plan, and guide users through various sets of content ranging from multi-part video series, to topically related materials and textbook vocab lists.

As far as users go, on one end of the spectrum, you have users who only use FluentU for the content itself. Our library of videos and audios is very large and already organized for you, translated into English, and completely annotated. These users usually already have a system for review they prefer, prefer not to review at all, or are in Chinese classes already and looking for engaging authentic content. Most of these users are intermediate and above and subscribe to our Basic subscription plan.

On the other end of the spectrum, are the users who use FluentU as their single source for most or all of their language learning and are Plus subscribers. Not only do they get all the content, but they have access to and can create decks (vocab lists), and are able to actually learn everything within the FluentU library using our personalized review tools. Learn mode integrates videos you’ve watched and tracks your progress so that we can do things like make sure clips you see are comprehensible to you and do an even better job recommending you content. All that adds up to a pretty complete learning package.

How big is the video library, exactly? How many FluentU-produced videos do you have now?

Jason: Our total count in the video library as I write this is 1251 videos, with 65 at newbie, 86 at elementary, 138 at intermediate, 257 at upper intermediate, 360 at advanced, and 340 at native. Of those, we’ve produced 10 ‘Courses’ of videos of our own, each about 5-10 videos apiece. Though, it’s ever-increasing because we publish at least 12 videos a week, sometimes more.

In addition to that we also produce our own audio dialogs, which we call ‘Audios’. They’re similar to some videos, but are more lesson-like and practical, and of course, don’t require the user to actually watch anything, which is great for mobile. (They’ll also be available offline on our upcoming mobile app.) Right now we have 228 of those spread across the levels, and also publish around 10 a week.

And as for ‘Decks’, which are vocab lists of various types available for learning via the Learn Mode, we have 124, and continue to publish more as well.

How have you been growing the library? Are you focused on particular levels, or topics, or styles of video? What are the plans for that?

Jason: We’re always looking for and preparing new videos. In general, we make sure to cover a wide range of topics and formats, and also keep difficulty in mind so that we can continuously publish a good mix of content. Though we also keep things like the overall library balance and user feedback and requests in mind as well. So far this has worked really well, so while we have no plans to change much in that regard.

How should learners decide what videos to watch on FluentU?

Jason: Browse! The videos in our library are divided into different topics, formats, and difficulties, which help users choose what to watch based on their interests and Chinese level. We also display the percentage of vocabulary the user already knows for each video, which allows them to chose videos that are more precisely at their level.

In addition to that, we have “Courses”, which if you don’t know exactly what to you want to watch or are looking for more structure, organize the content into playlists for you. Courses are also popular because they’re longer forms of content. You can slowly pick away at a course, with your next video, deck, audio, or learn mode session waiting for you every time you sign in, meaning you don’t always have browse for new content.

How do your difficulty levels relate to textbooks or other online services like ChinesePod or the Chinese Grammar Wiki?

Jason: We based our difficulty levels on a lot of things, but mostly a combination of our own knowledge and expertise (bolstered of course via sources like the Chinese Grammar Wiki), and other helpful standards like the new HSK levels. When actually determining difficulties, we consider things like speed and clarity, but linguistically we place a strong emphasis on frequency and usefulness to ensure that lower-level videos are filled with the stuff you really need when starting a language.

Can you explain the process for how you went about creating and filming your original video series?

Jason: When we first started compiling our library of videos, we realized there was a lack of quality, entertaining, video content for lower-level learners. There’s certainly stuff out there, as our current library reflects, but nothing as well-produced and linguistically-minded as we would have prefered. The stuff out there was either very entertaining but not practical, or very practical, but not entertaining. We wanted both, and so we decided to just make them ourselves. Essentially, we wanted to make sure our lower-level learners were getting as great of a video-learning experience as our more advanced users, and making some of our own videos was the best way to do that.

To produce them, we teamed up with a small independent film production company who we felt really understood our ‘vision’ with the videos. From there, we decided on what scenarios were most needed/wanted, wrote the scripts with our pedagogy in mind, and produced the videos.

You say the FluentU video series is for “lower-level learners.” Can you explain that a bit more? Is it for someone with a year of formal Chinese under their belt, or is it an absolute newbie, or someone who’s learned pinyin and a few basic phrases but nothing else, or what?

Jason: We’ve produced our own video series at the newbie level all the way up the upper intermediate level, but we made sure to produce more at the newbie, elementary, and intermediate levels simply because there’s less good material at that level.

The ‘newbie’ level courses are meant for learners with a little bit of understanding as to how the Chinese language works in particular in terms of tones, pinyin and characters, but without any prior master of them. Through a combination of the scripts, which are written for language learning, and a filming style that is meant to take full advantage of the video-learning format, we wanted to make understanding the content just come naturally, which is very important for newbies. To do that we emphasize things like repetition of key vocab, visual cues, slightly slower speech, etc.

The video player and learn mode also allow the user to start with pinyin first, and graduate up to characters when they’re ready. And finally, we also other courses meant specifically for learners who aren’t familiar with, or who need more practice with, things like tones and pinyin.

I’d say with a year of formal Chinese under your belt, you’d be just about at our ‘intermediate’ level. With ‘elementary’ being somewhere in between that, and what I’ve just described above.

How are your own videos different from other video-based learning material? What makes them special?

Jason: Well, I think for one we put a ton of care into making sure they were not only useful, educational, and pedagogically sound, but also interesting and worth watching. I think the biggest problem with a lot of language learning video series, is not unlike the problem that many textbook dialogs have, in that they end up being either boring, or unnatural and feel somewhat stilted in the end. We tried really hard to make sure ours were visually interesting (and hopefully even sometimes funny!) and also that our actors did their best to speak and act naturally, while still maintaining the clarity of speech that is so important to a language learning video. That’s probably the biggest difference in my mind.

That’s the end of this two-part review of FluentU. Check out Part 1 if you missed it.

15

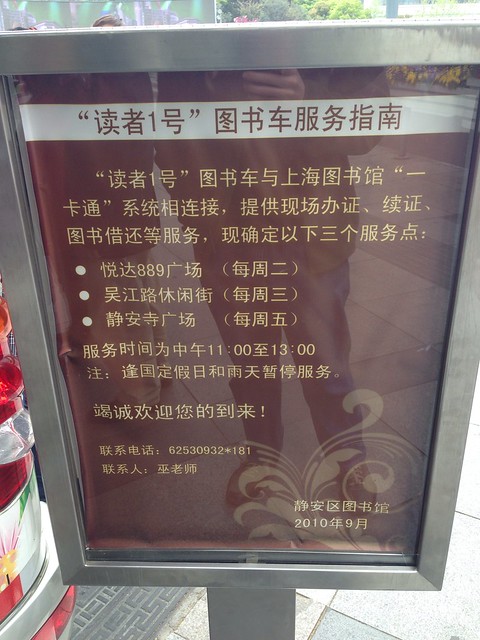

Apr 2014Shanghai’s Mobile Library

I was surprised to see a library-on-wheels in Shanghai’s Jing’an Park the other day. The vehicle is called “Reader No. 1” in English, “读者1号” in Chinese.

The mobile library visits various spots in Jing’an District three times per week, for two hours each time. According to the sign, this has been going on since 2010? I had no idea.

I wonder how many foreigners are using this service?

10

Apr 2014FluentU: a Developing Video-based Platform for Learning Chinese (1)

FluentU has quickly become the most talked-about video service for learning Chinese online. The site sports a clean, modern feel, and the team have been very responsive over the past year, as user feedback has informed a number of nice changes. Although I’ve been following FluentU’s development (and even met with the founder a while back), I haven’t reviewed the service myself until recently. It’s not a coincidence; I’m actually a bit skeptical of video-based learning (it’s really hard to get right), and I wanted to wait until FluentU got a few more features out before I reviewed the service.

For the most part, I’m going to assume that most of my readers have already heard about FluentU (it’s certainly not new anymore!), and I won’t provide an in-depth introduction to how the service works. This is part 1 of a 2-part series.

Why video?

Why video? This is a really important question. Working at ChinesePod, we were often confronted with the “why don’t you guys do video?” question. The logic seemed to be: “if audio is good, video is better.” ChinesePod has done a few experiments in video over the years, but never fully committed to it. The reasons are:

1. Professional video is much more labor-intensive than audio (by a factor of 5-10)

2. Users often say they want video, but don’t really want to pay extra for it (poor ROI)

3. Many users use audio material in a way that doesn’t work with video (e.g. listening while working out, or while driving)

What conclusions can I draw from this? Not a whole lot. Maybe video is just not a good fit for the ChinesePod brand. Building up a big fanbase over years and years, all centered on audio, probably doesn’t naturally lead to demand for video. If ChinesePod were to really commit to doing video, it would have to be a concerted, long-term effort, and more than just a few experimental videos.

FluentU, on the other hand, has focused on video from the start. In its early days, it utilized tons of clips from YouTube, which meant its resources could go into translation, vocab management, and other tools (rather than video production). More recently, FluentU has started producing its own professional video content.

Video is great for providing the full visual context of language, including both cultural elements and body language. This is especially powerful for learners not in China (learners which can also take advantage of the unblocked internet and faster speeds for viewing FluentU videos).

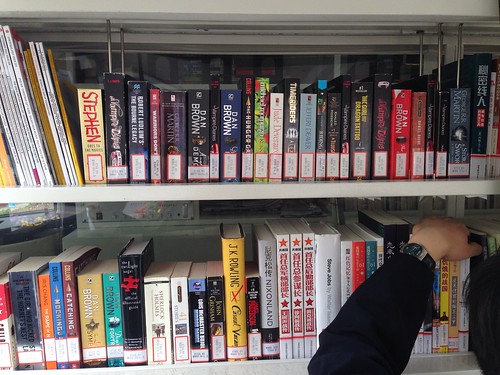

FluentU: the Video Player

FluentU does a great job of presenting video. The player is great, right down to all sorts of tiny details. If you know FluentU at all, you know this, so I won’t say too much here.

Some specific details I like:

1. Being able to loop a specific clip within a video.

2. Color coding in the video timeline so you can see where the dialog happens in the videos and where there’s no speaking going on.

3. Hovering on the subtitles automatically pauses the video, so you can check the meanings or pinyin of the words you’re hearing.

4. When you first select a video, you’re presented with the entire video transcript up front (which you can also download). This is especially useful for intermediate and above; if you can read enough to get the gist of the transcript, you don’t have to suffer through 5 minutes of a video before discovering it’s not what you want.

But there’s a catch… because FluentU makes extensive use of YouTube, it doesn’t work flawlessly in China. I have a VPN, of course, but it’s still a little slow. It’s usable, but the lag is quite annoying, I must admit. I imagine using FluentU on a fast (unfiltered) internet connection would be pretty awesome, though.

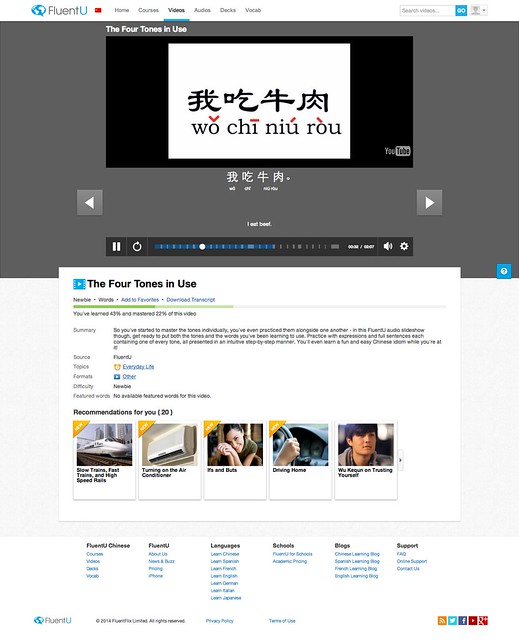

FluentU: Learn Mode

The is one of the key features I want to focus on. It wasn’t around in FluentU’s early free/beta days, and it has a lot of potential. Basically, “Learn Mode” is FluentU’s take on SRS, an idea which isn’t so great all by itself, but holds a lot of promise for enhancing other methods of learning.

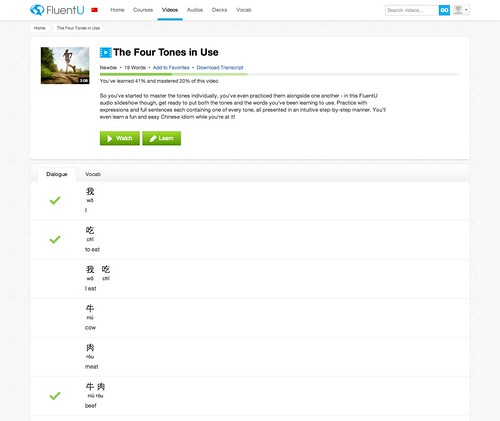

When you choose a FluentU video at your level that you’re interested in, you can choose between “Watch” and “Learn.” “Watch” is just watching the video, as expected. “Learn” takes you to a new interface which is focused on figuring out which words in the video you actually know, and familiarizing you with the ones you don’t know. This process should feel very familiar to anyone who’s used Anki or other SRS vocabulary review software, but FluentU has done its own take on SRS.

When you don’t “know” a word, you have the option of watching one or more short video clips which include the word. It’s a very cool cross-section of the word in action across all kinds of video content and contexts. Imagine that all those sample sentences you love so much in your favorite dictionary (or Chinese Grammar Wiki) were all mini video clips. That’s what it does, complete with transcript for each individual sentence.

After you “learn” the word and continue, the system will cycle back and test you on the words you should have “learned.” There are multiple-choice questions, fill-in-the-blank, and straight-up translation mini-quizzes for each word.

So I’m totally on board with the idea of extending SRS into something more interesting, and I like seeing innovation around the boring SRS model, but there are a few issues (which I’m sure FluentU is working on). First, if you’re in China using a VPN, the lag issue is even worse for these tiny clips than for the full videos.

Second, the “Learn this word” vs. “Already Know” dichotomy may be a little hard for some types of learners to deal with. There are just so many words we learners are working on in learning, which fall in that fuzzy region somewhere between “Learn this word” (as if it were new) and “Already Know,” that being forced to choose may be just a little agonizing.

If you choose “Already Know,” then BAM, that word is forever (?) on your “known” list, which might make you feel like you damn well better know it before clicking “Already Know.” Perhaps that’s the idea: getting you to browse clips more, and make fuller use of FluentU’s archive of annotated video. Fair enough. I just think it will be hard for some users (read: super-serious learners with perfectionist tendencies, like I used to be) to confidently click on “Already Know.”

One thing is for sure: the “Learn” mode offers a much more focused way to “study” FluentU’s video content, rather than just casually browsing. It really is a very different experience from the site’s main video-watching experience, more similar to a quiz than enjoying a TV show. I can see how this might attract some users and turn off others.

If FluentU can get “Learn” mode right and get more users actually using it, it has huge potential. Any learning service that can accurately determine what its users “know” is very well poised to offer an amazing, personalized learning experience. Right now, FluentU offers a little green strip next to every video displaying what is “known” (based on feedback from “Learn” mode). There’s a lot of potential here.

Mini-Interview with FluentU’s Founder, Alan Park

Me: The FluentU video player is fantastic! How did you design/develop it?

Alan: Thanks for the kind words! We designed/developed it through the same way that we develop the rest of the site: by going back and forth with our users and adjusting based on feedback, until they loved it. And then adjusting it some more.

FluentU has some great video content, but it seems to also be branching out into audio too. Are you having second thoughts about a “pure video” approach?

Alan: Our team doesn’t have many “sacred cows.” We experiment a lot and are always trying new things to make the best language learning site possible. We started with real-world videos because video has many advantages. Video is exciting, and it opens your eyes to a whole new world and culture. People talk naturally on video. It’s memorable and helps words stick. And most of all it’s fun. On the other hand, audio has 2 huge benefits: it’s cheaper to create than video, and it doesn’t require as much active engagement for the user as video. We’ve found that there is definitely a place for audio alongside video.

Is FluentU primarily aimed at individual self-study learners, or at schools and other institutions?

Alan: Our focus is individual learners, but many schools and institutions tell us that their students are loving FluentU.

You’ve launched other languages on the FluentU platform. What does this mean for Chinese? Will Chinese get any “special treatment” going forward, or are new features now “all or nothing”?

Alan: Chinese is our first language, so it will always get “special treatment.” And by virtue of the fact that there is pinyin and Chinese characters there is no way around it. Besides, it’s my favorite foreign language.

The “Learn” feature on FluentU is a unique take on spaced repetition. Is it popular with your users?

Alan: Yes, they love it. Instead of saying that it is a take on spaced repetition, I would say that spaced repetition is just one small part of it.

The “Learn” feature is really a personalized quiz for learning vocab through video contexts. Instead of learning vocab through flashcards, why not learn them through short video clips which are handpicked for you?

What’s next for the “Learn” feature?

Alan: We’re making it mobile friendly. Right now, it involves a lot of typing, which wouldn’t translate well for smartphone. Stay tuned!

Conclusions

Just a few takeaway points:

– FluentU has a great, learner-centric video player with awesome features and real attention to detail

– FluentU may not work well in China, even if you have a VPN

– FluentU has “Learn” mode, which may not be for all users, but it definitely takes FluentU well beyond “a site with a bunch of videos,” and looks very promising

In part 2 I’ll be looking at the FluentU-produced video series, with a more in-depth interview with Content Director Jason Schuurman.

04

Apr 2014A Realistic Look at the Challenges of Reading Chinese

The following is a guest article written by a Sinosplice reader, Julian Suddaby. I have followed it with some commentary of my own.

Warning: if you’re a member of the “Chinese is super easy” faction, this article might annoy you a little, but be sure to read through to the end!

How Many Characters?

by Julian Suddaby, 2014-02-13

Introduction

I asked Google “how many chinese characters do I need to learn” and the best sites I found pointed to linguist Jun Da’s website and used his data to argue that 3,500 characters should be enough for most people, being that you’ll know around 99.5% of the characters in general circulation. [1] Is that really enough?

Well, if you’ve got to that point, congratulations. It’s an achievement. But you may not want to stop accumulating characters just yet. Indeed, sad to say, at 3,500 you won’t even be able to read Jun Da’s name, being that 笪 is way down at frequency #5,231. [2] So how many, then, do you need to learn? Well, that depends on one question that you should ask yourself: what exactly do you want to read?

A Newspaper

Students often want to read Chinese newspapers. The Southern Weekly 南方周末 being a popular choice, I took the ten most popular articles over the previous thirty days and ran them through a computer program that checked them against Jun Da’s most frequent 3,500 characters. The results are fairly encouraging for the Chinese student, I think: if you knew the 3,500 you’d only encounter forty-four new characters over the course of those ten articles, and twenty-nine of those you’d only see once and so would probably just take a guess at from context and move on. But you’d possibly want to look up 甄, a pseudonymous surname given to the subject of one of the articles (and thus appearing thirty-five times); 闰, used in the name of a Zhejiang corporation which appears to have buried five hundred tons of poisonous chemicals in their backyard (seven appearances); and 驿, used in the name of a company involved in a online security breach (also seven appearances). [3]

So, while you probably shouldn’t throw out your dictionary just yet, it does seem that trying to read a newspaper won’t be a disheartening experience.

A Children’s Book

Children’s novels are another popular choice of reading material for language students. Shen Shixi is a well-regarded children’s novelist, whose Jackal and Wolf has recently been translated into English by Helen Wang. I ran an analysis on another of Shen’s novels, 《鸟奴》(lit. “Bird Slave”). This is, character-wise, much more difficult than the newspaper articles, with two hundred and one characters not in the top 3,500. Ninety of those are used more than once. As you’d expect from Shen, the “king of animal fiction”, animal-related vocabulary is one particular problem here, and you’ll probably end up very confused if you don’t look up 鹩, used two hundred and eighty-four times; 喙, used thirty-six times; and 獾, used twenty-two times. [4]

The novel is about two hundred and forty pages long, and so you should expect to find a character you don’t recognize on most pages.

A wuxia novel

Jin Yong’s novels remain firm favorites. Rather than starting with the four volumes and 1,300 pages of The Legend of the Condor Heroes 《射雕英雄传》, students might perhaps try A Deadly Secret《连城诀》, which is just four hundred pages or so. In those four hundred pages you’ll encounter two hundred and ninety-six characters not in the top 3,500.The most frequently used are from the protagonists’ names (水笙, 水岱, and 万圭), but there are plenty of new common nouns and verbs used multiple times as well. [5]

On a page-by-page basis, you should recognize more characters than in the Shen Shixi novel above. In terms of total characters, however, A Deadly Secret is more of a challenge.

A modern classic

Lu Xun’s A Call to Arms 《呐喊》, despite collecting stories he wrote at a very early stage of modern Chinese literary vernacularization, should not be much more difficult than the two novels above—at least in terms of basic character recognition. Two hundred and thirty unseen characters in total, with 闰 (remember that one from above?), 珂 (used in a name) and 锵 (a sound) taking the top three spots. [6]

Conclusion

Even from this very cursory analysis, it appears that if your goal is to read Chinese fiction comfortably without a dictionary, you’re going to need to recognize more than 3,500 characters. Chinese writers use characters well into the four or five thousand frequency range very regularly.

So although reaching 3,500 is worth celebrating, I wouldn’t stop trying to acquire characters just yet. Keep reading and dictionary-checking, and don’t abandon memorizing/spaced repetition if that’s something you find helpful. [7] You’ll still be coming across new characters for a long, long time…. [8]

- See http://lingua.mtsu.edu/chinese-computing/statistics/index.html.↩

- 笪 Dà (a surname here, but means “a coarse mat of rushes or bamboo”, with 旦 dān providing the phonetic). Here and later I’m using Wenlin as my main reference for character glosses.↩

- 甄 Zhēn (a surname here, but originally meaning “to make pottery” and thus composed of 垔 and 瓦, but with no phonetic clue), 闰 rùn (used in a name here, but means “intercalary”; the much more common 润 shares the same pronunciation), 驿 yì (used together with 站 to mean “post/courier station”; right-hand side is the phonetic, as in 译).↩

- 鹩 liáo (“wren”, with the left-hand side providing the phonetic), 喙 huì (“snout; mouth; beak”, with both 口 and 彖 radicals semantic; no phonetic clue), 獾 huān (“badger”, with the right-hand side phonetic).↩

- 笙 shēng (“reed-pipe instrument”, bottom is the phonetic), 岱 Dài (“Taishan mountain”, top is the phonetic), 圭 guī (“jade tablet”, cf. 挂 or 桂 for the pronunciation).↩

- 珂 (“a jade-like stone”, right-hand side is the phonetic), 锵 qiāng (“clang”, right-hand side is the phonetic).↩

- For the more technologically-oriented student, another option may be available: thanks to the increasing availability of texts in machine-readable formats students could run their own frequency analysis on a text they wanted to read and pre-learn characters they don’t already know. It’s a pity there don’t seem to be any easy-to-use programs or websites that offer this functionality.↩

- It should also be noted that single character recognition is only part of reading Chinese, and is not on its own a good measure of reading proficiency. That said, the relative ease of measuring character recognition and frequency may justify its limited use as a self-diagnostic and motivational tool for learners of Chinese.↩

The following is my response:

Interesting! This sort of helps make a case for the importance of graded readers. (Have you seen Mandarin Companion?)

While I know your intent is to SEEK THE TRUTH, the overall tone of the article is, unfortunately, a little discouraging for struggling learners. For me, this totally highlights the need for materials that give the learner a sense of accomplishment for having reached 300, 500, 1000 characters, rather than an incessant message saying, “STILL NOT GOOD ENOUGH.”

His response:

You’re quite right, I suppose I am a little too rigidly 实事求是 in the piece! I completely agree with you about the need to avoid the demotivating “still not good enough” feeling and message that permeates most Chinese teaching materials (how I remember my exasperation when the 高级 textbook still required fifty plus new vocabulary items per short text!). There’s really a huge need for more good reading materials with limited character/vocabulary ranges, and your graded readers look fantastic.

01

Apr 2014The Laziest Animated Movie Title Translations Ever

I remember when I first moved to China, I used animated films to practice Chinese quite a bit. I quickly discovered that Disney did an especially good jobs with translating (my favorite was the Chinese version of The Emperor’s New Groove). But I also started noticing something strange about a lot of these animated films’ Chinese titles… the word 总动员 appeared, somewhat inexplicably, way too often.

What is 总动员?

It was almost like a formula. In one word, what’s the movie about? That’s the main theme. Then just apply this formula:

[main theme] + 总动员

What was going on? I asked a number of native speakers abut this phenomenon, and none of them had paid the issue much notice. One bit of helpful information they did give, however, was that the word 总动员, in mainland China, is tied in the minds of many to some popular variety shows that came out around the year 2000. Specifically, they were 欢乐总动员 (“Joyous Zongdongyuan“) and 全家总动员 (“Whole Family Zongdongyuan“). Both were loud, fun, programs with lots of active people.

Pleco‘s dictionaries give the following definitions for 总动员:

- General/total mobilization

- General (or total) mobilization

- General mobilization (for war etc)

OK, obviously those aren’t the meanings they’re shooting for in the titles of cartoon movies.

Native speakers seems to have trouble giving an exact definition of this use of 总动员, but the feeling is clear: exciting, happy, lively, 热闹, with lots of people.

The Rise of 总动员

Not appearing in dictionaries did not stop this word from popping up in animated feature titles all over the place, starting shortly before 2000. Many were Disney films, but not all:

- Toy Story, Toy Story 2, Toy Story 3 (1995, 1999, 2010) 玩具总动员: “Toy Zongdongyuan“

- Joe’s Apartment (1996) 蟑螂总动员: “Cockroach Zongdongyuan“

- Finding Nemo (2003) 海底总动员: “Bottom of the Sea Zongdongyuan“

- Looney Tunes: Back in Action (2003) 巨星总动员: “Megastar Zongdongyuan“

- The Incredibles (2004) 超人总动员: “Superman Zongdongyuan“

- Cars, Cars 2 (2006, 2011) 赛车总动员: “Race Car Zongdongyuan“

- Ratatouille (2007) 美食总动员: “Gourmet Zongdongyuan“

- Bee Movie (2007) 蜜蜂总动员: “Bee Zongdongyuan“

- WALL·E (2008) 机器人总动员: “Robot Zongdongyuan“

- Planes (2013) 飞机总动员: “Airplane Zongdongyuan“

- Free Birds (2013) 火鸡总动员: “Turkey Zongdongyuan“

- Minuscule: Valley of the Lost Ants (2014) 昆虫总动员: “Ant Zongdongyuan“

This is not a complete list; rather, it’s an attempt to try to capture some of the biggest titles and the range that “zongdongyuan” covers.

OK, some of these seem to work OK… Specifically, Cars seems to deserve the treatment. I can’t help but feel that “Gourmet Zongdongyuan” (Ratatouille) could have been a much better title, though, as could have “Robot Zongdongyuan” (WALL·E).

To be fair, most of these movies actually do have multiple titles, and a casual check seems to indicate that the translators over in Taiwan are putting a bit more thought into the translations of animated feature film titles. Still, I’ve been seeing these zongdongyuan translations for years, and it especially stands out for Disney films, which tend to have excellent translations for the actual movies themselves, despite the total cop-out titles.

The Fall of 总动员

I was thinking the linguistics nerds like me were the only ones that gave this kind of issue any consideration, but fortunately at least some Chinese movie fans are also getting fed up:

最烦动画电影的中文翻译!动不动就什么什么总动员,总动员个屁呀!!有点技术含量行不行,不会翻译就直接用英文名也比这个好吧,都是文化人,怎么那么俗啊?这几年的电影都被总动员了,汽车、玩具、海底、美食、机器人,你知道什么是总动员不?我了个呸!!!!!看见这么二货的翻译就来气,这么好的电影弄了个蹩脚翻译!气死我了!想起来就来气。。。

A rough translation:

I’m so annoyed by the Chinese translations of animated films. It’s just this zongdongyuan, that zongdongyuan… screw zongdongyuan! Can’t you have just a bit of skill? If you don’t know how to translate, directly using the English title is better than this. You’ve all got culture, but now why so crude? In recent years all movies have been zongdongyuan-ized: cars, toys, bottom of the sea, gourmet food, robots… Do you even know what a zongdongyuan is? Bloody hell! When I see a shoddy translation like this it sets me off. How can such a good move have such a lame translation? I’m so pissed off! I get mad just thinking about it…

Anyway, the good news (for us translation purists) is that in recent years zongdongyuan seems to have worn out its welcome, and quite a few animated movies (including Disney/Pixar films) that almost certainly would have gotten zongdongyuan-ized 5 or 10 years ago did not: Brave, Tangled, A Bug’s Life, Madagascar, Rio, Up, Happy Feet (not 企鹅总动员!), Turbo, Mr. Peabody & Sherman, Despicable Me, The Croods (疯狂原始人, “crazy primitive men” rather than 原始人总动员!)… all escaped zongdongyuan-ization. (Whether or not those films’ titles have good Chinese translations, though, is another question… but at least they’re not quite so lazy.)

So did anyone else notice this lazy translation trend, or was it just me?

25

Mar 2014Sun Moon Eyeglasses

I recently noticed an eyeware shop called 日月眼镜 (literally, “Sun Moon” Eyeglasses”). This is a good example of a name that plays on common knowledge of characters and character components. The glasses themselves, of course, are unrelated to celestial bodies, but when you put the characters for sun (日) and moon (月) together, you get 明, a character which means “bright.”

Why “bright”? There are two reasons:

1. The word 明亮 (“bright”), is frequently used to describe attractive, alert, healthy young eyes. So it’s a good association.

2. Another association, although less direct, is that 明 can refer to eyesight itself. There’s a word 失明 (literally, “lose brightness”) which means “to lose one’s eyesight.” Logically, then, 明 can refer to eyesight, but there’s no word (of which I am aware) other than 失明 which uses 明 to mean “eyesight.”

Have you noticed any other Chinese shop or brand names that use “deconstructed characters” in their names?

20

Mar 2014Don’t Let the Air In

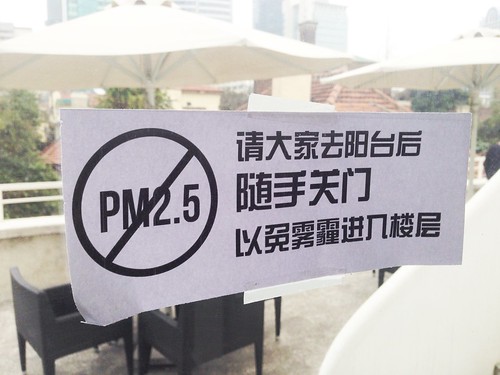

I saw this sign on the door of the AllSet Learning office building that leads out to the patio:

Here’s a closeup:

It reads:

> 请大家去阳台后

随手关门

以免雾霾进入楼层

Translation:

> Please, everyone, when going out on the balcony

close the door behind you

to prevent smog from entering the building

A young Chinese guy (presumably the one who put up the sign) came by our office to call our attention to the sign and ask for our cooperation. It was a little awkward because our window was open at the time (oops).

It’s weird… there’s a very traditional Chinese belief in a need for “fresh air” (even in the depths of winter). This air pollution problem is now quite visibly butting heads with that belief.

18

Mar 2014What Makes Bad Characters Readable?

I recently stumbled upon an interesting blog post titled The persistence of comprehension, which focuses on this handwritten Chinese note:

Now before you go too crazy trying to read it, know this:

Some time ago, Instagram user jumppingjack posted the above image of a note she left to her mum. She said that her brother secretly added extra strokes to the characters in the note. The result is interesting though: even though extra strokes were added, the note is still readable to most competent Chinese speakers.

That brother is kind of awesome. That is the kind of mischief I would have been all over as a kid, if only I had had Chinese characters at my disposal. The character substitutions are pictured at the right. (Note: not all of them are real characters.)

(Also, I totally sympathize with jumpingjack for writing the character 期 wrong, with the two sides swapped. I have done that way too many times myself.)

Try having a Chinese friend read the note and take note what gives them the most trouble. Read the original post for the note’s original content (in electronic text) and the author’s analysis and conclusions.

13

Mar 2014Ad to “Save More”

省 means “save” (as in “save money,” 省钱) or “conserve” (as in “conserve electricity,” 省电).

I feel like I’ve been seeing this particular in-store advertisement in Carrefour forever, but it’s time I pointed it out, because it’s a nice simple example of characterplay:

The text reads:

> 省更多

Which means, “save even more” (or “saving more”). (Check out this Chinese Grammar Wiki article on 更 if it’s new to you.)

Obviously, the clever part is sneaking the ¥ sign (representing money) into the 省 character.

11

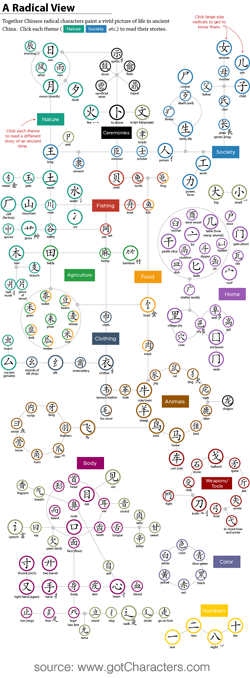

Mar 2014Interview with Kathleen of gotCharacters.com

I recently discovered gotCharacters, the personal project of Kathleen Ferguson. I was impressed by the logical organization of the character components, and the clean, attractive design of the site. It was clear that a lot of work went into the site, and it’s all available for free! The following is my interview with her.

What made you decide to create a new resource for learning Chinese characters?

I came to Chinese in 2006 as an adult learner and struggled to remember even the simplest of characters and pinyin. There were few resources that suited my learning style, so early on I started developing my own mnemonics. I’m sharing them on gotCharacters.com with the hope that it will make someone else’s learning experience easier.

How is your work on gotCharacters different from that of “Chineasy” (of TED Talks fame)?

Based on ShaoLan Hsueh’s TED Talk and a quick look at the Chineasy website, I think we share the same goal: offering ways, like visual aids and other mnemonics, to make characters stick and to make learning Chinese less intimidating.

In developing gotCharacters, however, my perspective is different. English is my first language, and I’m a Chinese language learner (an adult learner at that); to me, my content represents material I would have liked to have had earlier in my learning curve. As an example, gotCharacters includes lookalikes—characters that look similar (like 人 and 入, or 千 and 午). To the experienced eye the differences are clear, but for a newbie these characters can be indistinguishable (as they were for me).

How did you create all the content on gotCharacters? Do you have a team? Do you have Chinese teachers involved?

Most of the content started out as reams of handwritten notes accumulated over the years. With the benefit of time and mulling, an idea evolves and it’s sketched on a yellow pad. Then I use a variety of tools like graphics, Flash animations, audio recording, and eLearning software to develop the online content. Cecilia Lindqvist’s book China: Empire of Living Symbols and Claudia Ross’s Modern Mandarin Chinese Grammar are my two bibles.

I’m a visual learner, and animating characters brought them to life for me. My first animations were in 2010; in my mind’s eye, I could visualize 人 (person) walking, 飞 flying, and 马 rearing back on its hind legs and neighing. Every time I would come across these characters, as part of another character or as a stand-alone, I remembered the animation and thus the character.

Some ideas take time to come to fruition. I created the “Radical View” map (www.gotCharacters.com/radical-view) in 2011 as an independent project for class. Two years later I presented a more fully formed version at a World Language Teachers conference (my topic was “Overcoming the Challenges of Learning Mandarin: An American Student’s Perspective”), and the Chinese teachers’ enthusiastic response inspired me to make a color-coded, interactive version for the website, which was launched just this month.

As far as a “team” goes, I’m it. My family is supportive of my passion for Chinese and my desire to share that with others. My first Chinese professor, Wu 老师 at Central Connecticut State University, and several Hanban and StarTalk teachers, including Wang 老师, who currently teaches Mandarin at our Newtown High School, have been strong supporters as well.

How far have you come with your Chinese studies?

I’ve come a long way since 2006 when learning everything was a struggle and remembering how to count to ten was elusive. I’ve taken four college classes and continue to self-study using podcasts, books, Chinese movies, and anything else that helps me to learn and remember Chinese.

My reading proficiency is good, and I can carry on a basic conversation with a native speaker as long as they speak slowly and deliberately. My goal is to become fluent in Chinese, and though I have a long way to go, I’m enjoying the journey a great deal.

Did some of the characters you learned at a more advanced level influence how you designed the material for beginners to learn characters?

Technology has actually had the greatest influence on how I designed the material. With the evolution and easy availability of software and web tools, I can do more today than just a few years ago to extend the functionality and versatility of the content.

What’s next? Is this a growing business, or a side project?

It is my passion and avocation (I’m doing what I love), and I hope that I can make a living with it at some point. There is much more content coming to gotCharacters, and I look forward to opportunities to collaborate with others, to develop course curriculum, and maybe someday to teach characters. My mother always told us “Your goal should be just out of your reach” so my goal is for gotCharacters.com to become for Chinese what Kahn Academy is for math.

04

Mar 2014Translation Challenges: Roof Repair

I recently spotted this sign on the stairs leading to the roof of the AllSet Learning office building:

Here’s the Chinese text:

> 屋顶检修中,暂停使用,谢谢!

Literally, that’s:

> rooftop / examine and repair / in the middle of,

temporarily stop / use; usage,

thank you!

The translation offered:

> The roof is during maintenance. Stop using temporarily. Thank you!

The translation, while not great, is understandable. What stood out to me, though, were two issues frequently encountered in Chinese signs which can give translators a hard time:

1. Use of 中 after a verb

2. Signage etiquette

First let’s look at the first part: 屋顶检修中. The translator was on the right track with “during” for 中, and in adding “to be” into the English (its absence in Chinese is key to the difficulty of the translation), and also in converting the Chinese 检修 verb to a noun form for the English. But it still came out weird, because the translation demands a certain amount of linguistic flexibility with the concept behind 中. It’s hard to come up with a stock translation for this 中 that’s going to work in most cases. “During,” “in the middle of,” “in progress,” “underway,” “undergoing,” “in the midst of,” “currently” are all possibilities, but they’re certainly not easy for a non-native speaker to choose between, and not all are prepositions or prepositional phrases, either.

For the second part, 暂停使用, although the English is correct, it doesn’t contain the necessary degree of politeness we expect and demand from our signage in the English-speaking world. Chinese signs, while formal, just don’t feel as polite, and everyone is cool with that.

I have to give the translator props for converting the Chinese commas into periods in English, though. The Chinese “legal run-on” sentence being translated into an (unacceptable) run-on sentence in English is one of the most common mistakes made by beginner Chinese-English translators.

Anyway, a better translation would be something like:

> The rooftop is currently undergoing repairs. Please do not use it at this time. Thank you!

Obviously, that can be polished more.

It’s easy to laugh at bad Engrish, but in this case there’s nothing funny, and difficulties translating from Chinese to English (that go beyond simple word choice) can be indicative of difficulties that learners of Chinese will face with Chinese.

28

Feb 2014There Can Be Only One Lunch Time

After having lived in China for over 13 years, how has China changed me? Some changes are more subtle than others.

Photo by Yoshimai

Here’s a short exchange I had with a friend recently:

> Me: So are we doing lunch?

> Him: I can’t come at 12pm. How about 1pm?

> Me: OK, so after lunch?

> Him: What time do you eat lunch then? You’ve been in China too long…

It’s true that the Chinese are pretty rigid about their eating schedules, and now I realize that I have been reprogrammed. I think of 12pm as “the lunchtime,” with deviations as early as 11:30am or as late as 12:30pm acceptable.

Recently I had an evening meeting with an American AllSet Learning client that wrapped up around 10pm. He and his wife (also American) went out for dinner after the meeting, and I was a little incredulous that that was normal for them.

I realized that I now think of 6:30pm as “the dinnertime,” with deviations as early as 6pm or as late as 7:30pm acceptable.

This cultural norm for mealtimes also affects my business. Occasionally AllSet Learning clients want to do 2-hour Chinese lessons starting at 11am or 5pm. Those time slots make it impossible for the Chinese teacher to eat lunch or dinner at an even remotely acceptable time, so I have to explain that for cultural reasons, those are bad times for lessons.

I’m not sure exactly how “Chinese” my eating habits are, or if they’re sort of a hybrid of my original American ways and my Chinese life. One habit I’ve yet to “go native” on is breakfast. I like some Chinese breakfast (煎饼 in particular), but I frequently skip breakfast. This, of course, horrifies Chinese friends.

I think I used to fight this kind of change, these insidious creeping ideas that attempt to slowly win over my brain. This one is kind of hard to fight, though. The stomach wants what the stomach wants, and China’s been whispering in its “ear” for quite a while now.

25

Feb 2014Frozen’s “Let It Go” in Chinese Dialects

I was a little late to the party, but I finally saw Disney’s Frozen recently, and was very impressed. Later I did a bit of searching for different language versions of the movie’s hit song, “Let It Go,” and aside from discovering an impressive 25 language mashup version of the song, I also made another interesting find: Chinese dialect (/fangyan/topolect) versions of the song!

Of the videos included below, only the English, Mandarin, and Cantonese audio versions are official Disney productions. The others are fan creations, and as such, vary widely in quality. Some are translations of the original, while others are spoofs (恶搞) or partial spoofs. I’ve got them roughly in order of quality below (the worst at the bottom), so don’t say I didn’t warn you! (Links go to Chinese video sites (with ads); embedded videos are Disney’s official audio versions with fan-added subtitles from YouTube.)

- So here’s the original English version:

- Mandarin version (普通话版):

Note: Includes subtitles - Cantonese version (粤语版):

Note: Includes subtitles - Shanghainese version (上海话版): http://www.56.com/u55/v_MTA3MDEzNjc2.html

Note: Starts ut like a straightforward translations, but gets “Shanghainese creative” with certain parts - Taiwanese version (台语版): http://www.iqiyi.com/w_19rrck2e75.html

Note: male vocals, pretty hilarious in parts if you can read the Chinese subtitles - Chongqing-nese version (重庆话版): http://www.56.com/u47/v_MTA3MTc0Nzk2.html

- Changsha-nese version (长沙话版):

http://video.sina.com.cn/v/b/126402865-2708257315.html - Wuhan-ese version (武汉话版): http://www.56.com/u67/v_MTA2OTc3MzQ0.html

Note: male vocals - Dongbei version (东北话版): http://www.56.com/u88/v_MTA2OTU0OTI1.html

- Hangzhou-nese version (杭州话版): http://www.56.com/u50/v_MTA3MDEzNjcx.html

- Wenzhou-nese version (温州话版): http://bilibili.kankanews.com/video/av965714/

- Dalian-ese version (大连话版): http://www.56.com/u59/v_MTA2ODc3NjMy.html

- Sichuan-ese version: (四川话版): http://www.56.com/u16/v_MTA2ODYwNjA1.html

I’m no expert on any of these dialects/fangyan, so if anyone has any corrections to make, please leave a comment.

[Side note: it was kind of weird adding “-ese” or “-nese” to some of those place names, so I used a hyphen to make it clearer which places the dialects/fangan came from.]

21

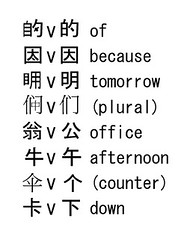

Feb 2014Letters Embedded in Characters

Here’s a creative use for the alphabet:

The Chinese reads:

> 笨苹果的

英语

学习法

…or, “Stupid Apple’s English Learning Method.”

(Hopefully it’s not just hiding letters in Chinese characters.)

19

Feb 2014V-Day Marketing Opportunism

I’ve grown accustomed to interesting examples of Chinese capitalism (I often say the Chinese are more capitalist than us Americans), but I was presently surprised to see this (sorry it’s not the greatest photo):

So on Valentine’s Day, demand drives the price of roses up to something like 30 RMB per flower (give or take). Normally it’s around 10 RMB (which is already kind of high).

Well, this real estate developer decided to give away free roses on the evening of February 14th, right on the street near Zhongshan Park, with this heart-shaped advertisement attached. Quite clever!

I know for a fact that most people immediately removed the ad and kept the rose, but I do wonder if the tactic proved fruitful for them or not.

13

Feb 2014A Pinyin Typing Shortcut for Crazy Characters

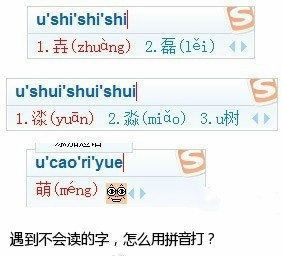

Pinyin is generally great for typing (learn it!), but there’s not much it can do for you when you’re trying to type a character you don’t know how to pronounce. This has always been the case, until recently, when a few of the popular pinyin input methods have started adding a few new tricks.

Basically, you first type “u” (a letter no valid pinyin syllable begins with), and then you type out the common names of the character components. You can see it in action in the image (the apostrophes are inserted by the pinyin input method itself to show how pinyin syllables are interpreted).

More text-friendly breakdown of what the image shows:

– 壵 (zhuàng) = 士 (shì) + 士 (shì) + 士 (shì) = u’shi’shi’shi

– 磊 (lěi) = 石 (shí) + 石 (shí) + 石 (shí) = u’shi’shi’shi

– 渁 (yuān) = 氵 (sāndiǎnshuǐ) + 水 (shuǐ) + 水 (shuǐ) = u’shui’shui’shui

– 淼 (miǎo) = 水 (shuǐ) + 水 (shuǐ) + 水 (shuǐ) = u’shui’shui’shui

– 萌 (méng) = 艹 (cǎozìtóu) + 日 (rì) + 月 (yuè) = u’cao’ri’yue

[Side note: best English translation for the slang word 萌 “adorbs”??]

The bad news is that this doesn’t seem to work on Mac OS X or iOS. I hear from reliable source that it works on Sogou pinyin for PC and Google Pinyin (for PC). Does it work on Android devices running Google Pinyin?

Let me know in the comments if it works for you, and share some interesting examples of what works and what doesn’t work. Thanks!

07

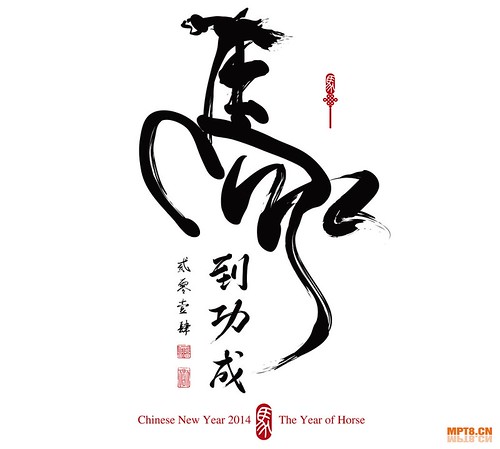

Feb 2014The Year of the Horse Chengyu

This is my second “Year of the Horse” Chinese New Year in China, and there’s one thing I’ve noticed: a certain chengyu (Chinese idiom, typically 4 characters long) gets thrown around like crazy in Chinese New Year’s greetings.

That chengyu is 马到成功.

There are a few interesting things about this chengyu, and some points worth exploring.

Is it worth knowing?

Like many learners, you may not want to junk up your brain space with too many useless chengyu. So is this one worth it? Well, it sure gets liberally tossed around at the beginning of the Year of the Horse, that’s for sure.

But aside from that, it’s not a terribly uncommon chengyu. I’ve learned it without trying just by living through one Year of the Horse CNY, and you probably can too, if you live in China or if you’re tuned into Chinese media for the holiday. Tons of repetition of this chengyu.

What does it mean, really?

The nice thing about 马到成功 is that its components are so easy:

– 马: horse (easy!)

– 到: to arrive (easy!)

– 成功: to succeed (not bad, intermediate-level vocab)

It’s all high-frequency vocabulary, so that’s great. What does it really mean, though? “Horse arrives, success!” Something is missing. Is there some mystical luck-horse that runs around providing success to all it encounters? Not exactly.

If you look up 马到成功 in a dictionary, you get something like this:

> win instant success

Or, more literally:

> win success immediately upon arrival

OK, so if you take 马到 to mean “instant,” than isn’t it just the same as 马上, “immediately?”

But it’s not. At Chinese New Year, the chengyu is used in New Year’s wishes to others. If you were wishing people “马上成功” it sounds like they’ve already started something, and you want them to succeed immediately (like really soon!). Wishing them 马到成功 is wishing a speedy success to whatever endeavor someone undertakes. That makes a lot more sense.

OK, but does that explain why it’s 马到? Not really. Fortunately Baidu has the answer (in Chinese, of course). The chengyu actually refers to ancient warfare, in which cavalry played an important role. If your cavalry could get there on time right as the battle began, you’d frequently be assured a swift victory. (There’s a more complicated story behind the chengyu which Baidu relates, but it’s related to cavalry.)

This isn’t to say that Chinese people have images of cavalry slaughtering their enemies as they wish their friends 马到成功. In fact, most Chinese people probably aren’t aware of the origin of the saying. If you Baidu image search it, you see a whole bunch of images of horses frolicking around, not an enemy soldier in sight.

Using it

Even though the 马到成功 literally means “swift success,” you can also use it by itself to wish someone success in the New Year. You don’t need to add 祝你 in the front for “I wish you” (even though it’s not wrong to say that).

A common greeting that won’t stretch any intermediate learner’s abilities is:

> 新年快乐,马到成功! (Happy New Year, and swift successes!)

And with that, I wish everybody a 马到成功 in their Chinese studies!

04

Feb 2014May the Horse Be With You

I wasn’t expecting Star Wars to get in on the CNY festivities, but here it is:

The pun is (in traditional characters originally):

> “星”年快樂

In simplified, that’s:

> “星”年快乐

新年快乐 means “Happy New Year.” The pun replaces 新 (xin: “new”) with 星 (xing: “star”). The two are both first tone, and do sound very similar in Chinese (in fact, many native speakers don’t carefully distinguish between the “-n” and “-ng” finals of many syllables), and Star Wars in Chinese is 星球大战 (literally, “Star War(s)”).

Thanks, Jared, for bringing this video to my attention!

28

Jan 2014Advertising the Year of the Horse

It’s almost the Year of the Horse (马年) in China, and you can see it in advertising all around China. Here are three examples from Shanghai:

This first one incorporates the traditional character 馬 (horse) into the design.

Using the word 马上 (literally, “on horseback,” it means “right away”) is the easy way to go.

This one uses the internet slang 神马 (literally, “god horse”), which is sometimes used in place of 什么 (“what”).

Happy Year of the Horse!

23

Jan 2014Chinese Grammar Points Used by a 2-year-old

My daughter is now two years old, and she’s well on her way to simultaneously acquiring both English and Mandarin Chinese (with a little Shanghainese thrown in for good measure). We’re using the “One Parent One Language” approach, and it’s working pretty well.

I’ve taken a keen interest in my daughter’s vocabulary acquisition, but recently I’ve also been paying close attention to her grammar in both English and Chinese. Those that follow the debate regarding order of acquisition and whether or not a child’s natural acquisition should be closely mirrored by language learning materials should not be surprised to learn that her grammar pattern acquisition is all over the place. What I mean is that the grammar patterns she can or cannot use do not match well to what a beginner learner of Chinese should or shouldn’t be able to use after a year of study.

So what I’m going to do in this post is briefly comment on her mastery of some well-known grammar points, and also highlight some of the more surprising ones. I’ll be using the Chinese Grammar Wiki’s breakdown by level for reference (the order, low to high, is: A1, A2, B1, B2).

Grammar Points My Daughter Can Use

- Measure word “ge“ (A1)

So she’s counting things the Chinese way, with 个. Picked this one up pretty quick, it seems. - “Er” and “liang” (A1)

I was wondering how quickly she’d master the use of 二 and 两, but she had it down easily, before she was two. (Obviously, she has no need for most of the fringe cases; she just needs to count stuff.) I know her waipo (maternal grandmother) practiced this one with her a lot. - Expressing possession (A1)

It took her a while to get the hang of 的 for possession, just as it took her a while to get the hand of “‘s” for possession in English. Neither is totally consistent (she sometimes forgets to use them), but she’s basically got them down. - Questions with “ne“ (A1)

When an adult learns Chinese, you learn the pattern “____ 在哪儿?” to ask where something is. My daughter totally skipped that, and uses 呢 exclusively to ask where things are. This is a use of 呢 you don’t normally learn as an adult student of Mandarin until a bit later, but there’s no arguing that it’s simpler! Kids like linguistic shortcuts. - “meiyou” as a Verb (A1)

She doesn’t know that 没 is a special adverb of negation used with 有. She just knows what 没有 means as a whole. And it works! - Negative commands with “bu yao“ (A1)

Yeah, two year olds can be a bit demanding and uncooperative. 不要 is a key tool in her arsenal of terribleness, and it’s one of the few Chinese words that she likes to use when she’s otherwise speaking English, as well. - Standard negation with “bu“ (A1)

Again, very useful when she wants to be contrary. She uses 不 pretty indiscriminately, putting it in front of verbs, verb phrases, and adjectives, but sometimes also nouns. - Expressing “with” with “gen” (A2)

I say she “knows” this, but she uses it exclusively with the verb 去, for talking about “going with (someone).” Again, it gets the job done! - Change of state with “le” (A2)

This is another one of those grammar points that she has a very limited mastery of, but makes good use of. She knows and uses the phrases “来了,” “走了,” and a few others. (Interestingly, she often uses “来了” as a substitute for the existential 有, meaning “there is.”) - Negative commands with “bie” (A2)

Again, a great pattern for the terrible twos. - Reduplication of verbs (A2)

She uses this with specific, high-frequency verbs, like 看 (看看). - “-wan” result complement (B1)

Obviously, she has no clue how to use complements. She learns phrases, and the phrase “吃完了” gets used a lot. (Her English equivalent for this is “finished” or “done,” not “finished eating” or “done eating.”) - Expressing the self-evident with “ma“ (B1)

嘛 (not 吗) is notoriously tricky for adults to get the hang of, but my daughter jumped right in and started using it early. Sometimes it feels like she’s not using it quite right, but clearly that doesn’t faze her. You’ll notice that any Chinese 3-year-old uses 嘛 pretty liberally, so it’s clearly something that kids pick up really quickly, and adult learners over-analyze.

Grammar Points My Daughter Cannot Use

- Personal pronouns (A1)

This might seem surprising, but these ubiquitous, abstract words for expressing “I” (我), “you” (你), and “he/she/it” (他/她/它) are totally unnecessary in the beginning and ignored by kids for quite a while. My daughter is just know starting to use “I” and “我,” but she’s still just experimenting. (Previously, she used “baby” and her own name instead of “I.”) - “Can” with “hui” “neng” and “keyi” (A2)

Here’s something elementary learners spend quite a bit of time mastering, but my daughter has decided to shelve the use of modal verbs 会, 能, and 可以 altogether, for the time being. (She seems to be making some progress on English “can,” however.) - Basic comparisons with “bi” (A2)

Doesn’t need it, doesn’t use it. She confines her “comparisons” to just nouns and adjectives. - “Shi… de” construction (B1)

Yeah… doesn’t need 是……的, doesn’t use it. She hears this pattern in questions all the time, however. She’s slowly soaking up the input. - “Ba” Sentence (B1)

This one is notoriously difficult for adult learners, and kids avoid it for a while, too, as it turns out. My daughter definitely understands the structure, though, whether or not she even notices the presence of 把 in the sentences she understands. She never uses it. - “Bei” sentence (B1)

She definitely doesn’t use 被. No need for passive at all, and she doesn’t hear it much either, at this point. I’m sure linguists have studied at what point kids acquire passive constructions and why, but it’s clearly a lower linguistic priority for kids.

Conclusions

None of this is scientific; these are just casual observations. Watching my daughter simultaneously acquire two languages, I’ve done a lot of thinking about the differences between the way children and adults acquire languages. Whether or not there are neurological limits is still being debated, but it’s clear to me that there are differences, in practice.

What I’m seeing:

- Kids can get by without pronouns. Without pronouns! How many adults could do that, even after being told they’re not high priority? I’ve personally observed quite a few people that try to start learning a language by translating the English of what they want to say, and their first question is frequently, “how do I say ‘I’?” You don’t need to start this way, but adults feel they need to.

- My daughter was not at all tripped up by measure words, but after mastering numbers 1-10 in both languages she zoomed ahead with her Chinese numbers, while the irregular teens in English (“eleven,” “twelve,” “thirteen,” etc.) really slowed her down.

- By putting utility above all else, my daughter frequently starts “using grammar patterns” before she understands how they work at all, simply by learning phrases. I don’t mean she doesn’t intellectually understand grammatical concepts (of course she doesn’t), I mean she doesn’t even know that she can put 完 on the end of other actions; she just knows how to say 吃完了 when she finished eating, because that’s all she needs from 完 at this point. The memorized phrase will be generalized into a “pattern” when it becomes necessary. This is actually a point that adults should really learn from: over-analysis frequently slows adults way down and delays meaningful communication. This is also the logic behind the approach to learning 了 on the Chinese Grammar Wiki; learning patterns in a gradual process is actually the best way to learn how to use 了. And it’s usually best to memorize a phrase you need first, then generalize later.

There’s a lot I could say here, but I’ll stop now. Comments are welcome! I’m especially interested in hearing about relative order of grammar acquisition of my readers’ children.

UPDATE: Grammar points at 2 and a half