The Year of the Horse Chengyu

This is my second “Year of the Horse” Chinese New Year in China, and there’s one thing I’ve noticed: a certain chengyu (Chinese idiom, typically 4 characters long) gets thrown around like crazy in Chinese New Year’s greetings.

That chengyu is 马到成功.

There are a few interesting things about this chengyu, and some points worth exploring.

Is it worth knowing?

Like many learners, you may not want to junk up your brain space with too many useless chengyu. So is this one worth it? Well, it sure gets liberally tossed around at the beginning of the Year of the Horse, that’s for sure.

But aside from that, it’s not a terribly uncommon chengyu. I’ve learned it without trying just by living through one Year of the Horse CNY, and you probably can too, if you live in China or if you’re tuned into Chinese media for the holiday. Tons of repetition of this chengyu.

What does it mean, really?

The nice thing about 马到成功 is that its components are so easy:

– 马: horse (easy!)

– 到: to arrive (easy!)

– 成功: to succeed (not bad, intermediate-level vocab)

It’s all high-frequency vocabulary, so that’s great. What does it really mean, though? “Horse arrives, success!” Something is missing. Is there some mystical luck-horse that runs around providing success to all it encounters? Not exactly.

If you look up 马到成功 in a dictionary, you get something like this:

> win instant success

Or, more literally:

> win success immediately upon arrival

OK, so if you take 马到 to mean “instant,” than isn’t it just the same as 马上, “immediately?”

But it’s not. At Chinese New Year, the chengyu is used in New Year’s wishes to others. If you were wishing people “马上成功” it sounds like they’ve already started something, and you want them to succeed immediately (like really soon!). Wishing them 马到成功 is wishing a speedy success to whatever endeavor someone undertakes. That makes a lot more sense.

OK, but does that explain why it’s 马到? Not really. Fortunately Baidu has the answer (in Chinese, of course). The chengyu actually refers to ancient warfare, in which cavalry played an important role. If your cavalry could get there on time right as the battle began, you’d frequently be assured a swift victory. (There’s a more complicated story behind the chengyu which Baidu relates, but it’s related to cavalry.)

This isn’t to say that Chinese people have images of cavalry slaughtering their enemies as they wish their friends 马到成功. In fact, most Chinese people probably aren’t aware of the origin of the saying. If you Baidu image search it, you see a whole bunch of images of horses frolicking around, not an enemy soldier in sight.

Using it

Even though the 马到成功 literally means “swift success,” you can also use it by itself to wish someone success in the New Year. You don’t need to add 祝你 in the front for “I wish you” (even though it’s not wrong to say that).

A common greeting that won’t stretch any intermediate learner’s abilities is:

> 新年快乐,马到成功! (Happy New Year, and swift successes!)

And with that, I wish everybody a 马到成功 in their Chinese studies!

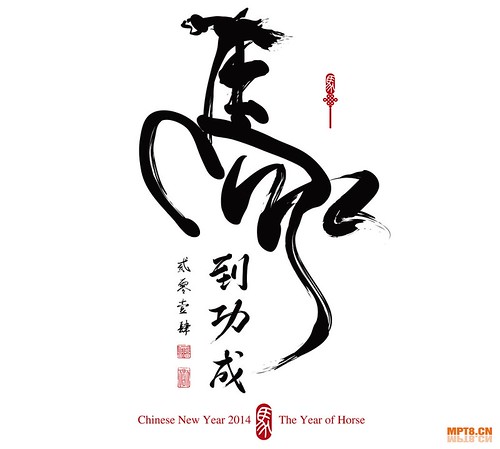

You didn’t mention that in the calligraphy the order of the characters is different: 马到功成, which is how I was taught the chengyu, but the native speaker who taught it to me couldn’t explain why.

Charles,

Sorry, I’m not sure what you mean… it’s all the same order, no? 马到功成.

I think this is what Charles is getting at:

马到成功 – chengyu as written in the article.

马到功成 – as written in the picture (calligraphy), and in your reply to Charles’ comment above.

The order of the last two characters is different, though I’m assuming it doesn’t change the meaning at all?

Thanks John!

Wow, I totally did not even notice that. It’s just a case of seeing what you expect to see, I guess.

Anyway, according to the dictionaries I consulted, the meaning is the same, although 马到功成 is not used much in modern times. 马到成功 is the norm.

John,

Great post! I wonder it was a typo: the meaning of 成功 is “not bad”?

Also, when you mentioned why not 马上, I thought you were going to talk about the popular “pun” this year, as in “马上发财“ or “马上有钱” etc. I’m sure you heard of those 🙂 So I guess you CAN actually say 马上成功 to follow the trend. (but it might be too confusing for beginning leaners…)

well, ignore my second comment, just saw one of your previous posts of mashang…

Oops, I made a mistake there. “Not bad” was supposed to refer to the difficulty of the word (compared to the other two, which are totally “easy”). I totally left out the meaning of the word by accident. Thanks for pointing it out! Fixed.

Yeah, true, there’s lots of 马上 going around, but it’s a lot easier to understand, and the exact meaning of 马到成功 used to bother me, so I thought I’d write about that.

Nice post John!

Right, the calligraphy is 马到功成. The structure is: If A, then B, like saying “as soon as the horse arrives, the deed succeeds.” Similar Chengyu 水到渠成

I’m confused by these people saying 马到功成 is “the calligraphy”. Surely calligraphy is the collection of artistic styles of writing, and 马到功成 and 马到成功 are two variant forms of the same 成语?

And looking at the two variant forms now, would I be right in thinking 马到功成 looks like an older, more Classical version of the 成语, and 马到成功 like a modern reinterpretation? Perhaps not – a cursory glance at my 中华成语大词典 has a citation of the 成功 version dated to the Yuan, and no cites for the 功成 version. Still, considering that typing 马到功成 into Baidu gets this: http://tinyurl.com/lt58hhb as the first suggested search term, I guess there’s a fair bit of confusion out there.

Here: http://tinyurl.com/mzgerfs is the tiny little bit Baidu Baike has to say on 马到功成. I note it does not describe this version of the 成语 as “the calligraphy” or “书法”.

Hi Chris, the calligraphy is mentioned because John was going to talk about the Chengyu 马到成功 while the picture (it happens to be a calligraphy work by the way) he quotes, slightly unnoticeable, is 马到功成.

As much as I can understand, both of them are Chengyu. The usage of 马到成功 is more common though, because it follows regular (modern Chinese) grammar.

You may encounter some variant forms of the same Chengyu, don’t be surprised. For example, 水滴石穿/滴水穿石, 受益匪浅/获益匪浅 etc.

Ah, thanks, but now I feel silly. I hadn’t noticed that’s how it was in the calligraphy at the top of the post.

Don’t feel bad, Chris… there was a lot of not noticing going on surrounding this post. 🙂

Dude. They are not referring to “the calligraphy version” generally. There is NO SUCH THING as a calligraphic-only version of a chengyu. They are just pointing out that the particular picture featured in this blog entry (which happens to be done in calligraphic style) uses the variant 马到功成, but in the text explaining the chengyu only the OTHER variant 马到成功 is used. They are explaining this specific case of inconsistency to the author.

Thanks for your insights, John! You might find 歇后成语 (xiehouyu which have a chengyu as a second part) a valuable source for getting hints on the literal meaning of chengyu. Because such xiehouyu deploy the method of reviving the literal (= original?) image of the second part (i.E. chengyu) through their first, descriptive part to create a pun, like in this example:

樊梨花下西凉 —— 马到成功

(The Turkish woman warrior) Fan Lihua takes Xiliang –– (lit.) she wins the battle as she arrives by horse, (fig.) immediate success.

There´s a special dictionary containing as many as 4.500 xiehouchengyu (though not the one above): 王士均,陈靓:歇后成语词典, 上海辞书出版社 2006.