Time, Textbooks, and Podcasts

I’ve been in China 18 years now, and started working at ChinesePod over 10 years ago. I remember when we first started, we were creating lessons about simple everyday interactions which simply did not exist in any available textbook. The one that comes to mind is a Newbie lesson from 2006 called Using a Credit Card. The super useful question was:

现金还是刷卡? [Cash or credit?]

This lesson was so useful because credit cards had only fairly recently been introduced to China, or at least only in recent years become common. No textbooks taught 刷卡 (“to swipe a credit card”) because textbooks typically needed something like 10 years to catch up with development of that sort. So they weren’t even close, happy to focus on iterations of the classic “Going to the Post Office” chapter, which was rapidly becoming irrelevant in modern life.

In the years to follow, ChinesePod did lots of lessons involving 手机 (“cell phones”), and later 智能手机 (“smartphones”). I observed over time as textbooks struggled to update to even include the word 手机 at all.

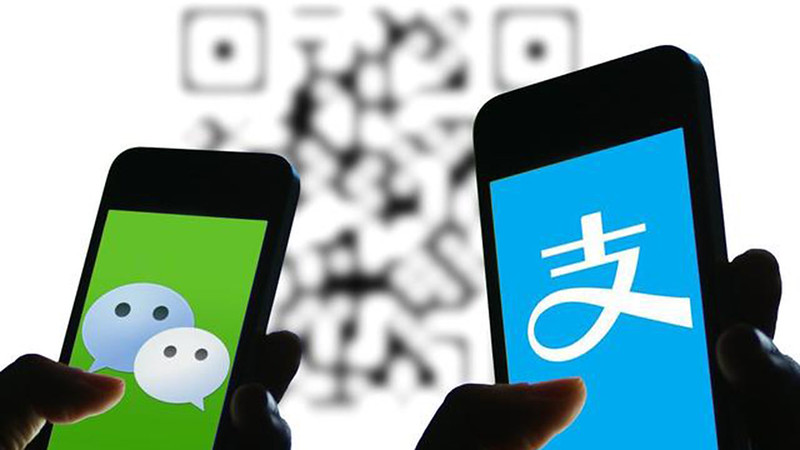

The irony is that in 2018, even the lesson Using a Credit Card is now almost irrelevant itself. It’s so easy to bind your bank’s debit card to your WeChat or AliPay account, and Chinese consumers, for the most part, don’t like living on credit. So now the most important question you always hear when you buy something is:

支付宝还是微信? [AliPay or WeChat?]

It doesn’t appear that ChinesePod has this exact Newbie lesson yet, but it should. This new trend is especially important to point out to China newbies because in this particular regard, China is actually ahead of western countries, a fact which takes a lot of visitors by surprise.

I oversaw lesson production at ChinesePod for almost 8 years, and one thing became clear about the business model: the ChinesePod users wanted new lessons continually added. There were some in the company that considered this a problem, because the archive had already grown large enough to meet almost learner’s needs. Looking back from 2018, it’s easy to see that a lot of those lessons weren’t actually targeting serious communication problems for learners. On the other hand, some regular new content is also necessary in this age of rapid technological growth, where Chinese society develops quickly in new directions that no one can anticipate. Textbooks might find keeping up impossible on a traditional publishing cycle, but even for internet companies, it’s a challenge.

共享单车 is another incredibly useful topic that didn’t exist back in the day!

Totally, and it’s another good example of something that’s different in China from what’s available in the west (for most western cities, anyway).

Speaking of rapid technological growth, the topic of the lesson could be 共享电动滑板车

扫码 is word that I also learned only when trying to pay somewhere… I frequently travel to China, but don’t live there, so I do not have a Chinese bank account and thus haven’t figured out how to use WeChat or Alipay to pay, which makes me feel like being a country bumpkin of some sort. If they 刷不了 (yikes!) my foreign credit card, I have to pay cash, which nowadays is almost embarassing…

And you are right about Chinesepod’s need to keep up to current developments by adding new content. However, also their database is an amazing source of spoken language that can help you build a solid foundation. After that at some point, you will have to jump into the real world anyway and pick up the stuff you need where you need it.

I’ve noticed the problem with old content not getting refreshed even more acutely in similar monthly membership sites aimed at programmers. Whereas *most* Chinese you learned 20 years ago is still useful, a lot of content revolving around web frameworks from 2 years ago is already dated.

A lot of sites also tend to resist redoing introductory lessons, in favor of trying to cover more new topics, too. This is usually good for marketing and search engine traffic in the short term, but it’s somewhat self-defeating in the long run since beginners keep pouring in and the introductory content gets viewed the most.

I think CPod’s model is fine. Continuing to make content while large numbers of customers continue to pay each month can be a great business.

[…] originally designed to be coin-operated, and modern Chinese cities are using cash less and less, opting for mobile payment giants AliPay and WeChat whenever possible. So what’s a gachapon operator to […]

I can understand there must have been “some” pushback against continuous content production due to what must have been a relatively high cost. So I am forever grateful to you, JZ and the teachers and voice actors at CP for successfully pushing for and achieving that continuous production of such stunningly high quality lessons.

Although you say in hindsight many of those lessons were not addressing “… serious communication problems for learners”, as a long time CP subscriber, I beg to differ. The newbie/beginning/intermediate learner’s serious communication problem is: They can’t (bleeping) understand Mandarin as natively spoken, much less make themselves understood to a non English-speaking native.

As you are aware, hearing/seeing/speaking words and phrases in multiple and diverse contexts seems to help the brain “triangulate” and acquire language more effectively, and that’s one of the things your influence and leadership successfully achieved at CP with a diverse lesson content and an obvious attention to quality.

So I guess one point is don’t lose sight of why you guys took the approach you did. The other point is that a side effect of continuous production was that you kept getting better at it. It allowed for evolution in the way you thought about and produced lessons.

So thanks for your work at CP and for continuing to fill gaps in available learning materials with Mandarin Companion!

Don,

Thanks for the kind words.

Don’t get me wrong… I’m not saying we should have produced only 20 lessons per level and called it a day. I’m still a big believer in creating lots of content in order to provide choice for the learner. The concept of learner autonomy is an important one.

I’m just saying there were lessons like “Dog Personalities” that maybe weren’t addressing anyone’s real needs, and weren’t really drawing in lots of listeners either. I don’t regret lessons like “Godzilla in Shanghai” or “Death by Ninja,” though!