25

May 2010A Chinese Take on the Baseball Metaphor for Sex and Dating

Most Americans are familiar with the “base system” baseball metaphor for physical intimacy. If you’re not familiar with it, you might check out this XKCD comic for the complicated version, or this excerpt from baseball metaphors for sex from Wikipedia:

- First base is commonly understood to be any form of mouth to mouth kissing, especially open lip (“French”) kissing.

- Second base refers to tactile stimulation of the genitals over clothes, or of the female breasts.

- Third base refers to groping naked genitals (handjob or fingering), or oral sex.

- Home run (or rounding the bases, scoring a run, hitting a home run, scoring, going all the way, coming home, etc.) is the act of penetrative intercourse.

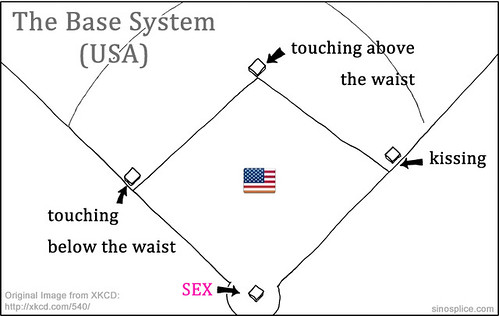

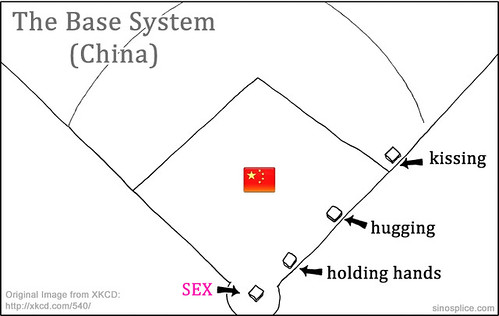

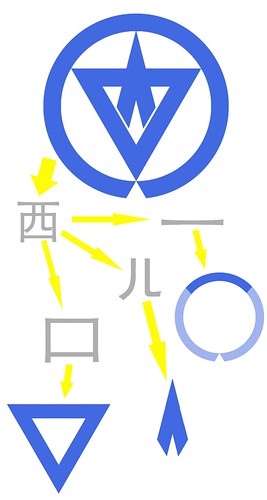

For the visual-oriented among us, here’s a graphic (adapted from XKCD’s complex version):

I can understand that a country little love for baseball might be confused by this metaphor system. Apparently even Europeans are confused by it. However, some people in China have picked it up, but in the process changed the system (reference link removed due to malware at destination website]):

- “一垒”代表拉手,

- “二垒”代表拥抱,

- “三垒”代表亲亲,

- “本垒”代表XX

Translation:

- “First base” represents holding hands,

- “Second base” represents hugging,

- “Third base” represents kissing,

- “Home” represents _____

Clearly, this is a whole ‘nother ballgame the Chinese are playing, and their playing field looks like this when superimposed onto the American field:

So much for “rounding the bases!”

Thanks to Marco from EnglishPod for bringing this interesting cultural difference to my attention!

21

May 2010Orlando Kelm on Language Power Struggles

To follow up my recent massive post on Language Power Struggles, I’d like to highlight the responses of Dr. Orlando Kelm, a professor of linguistics, teacher of many years, and learner of multiple languages. Dr. Kelm’s experience is largely with Portuguese and Spanish, but he’s also studied Japanese and Chinese, among other languages.

Dr. Kelm’s three main points were:

1. Chinese perception of use of English: There is something interesting about Chinese adoption of Putonghua as a lingua franca, despite all of the regional dialects and local languages. As related to use of English, it’s almost as if people accept their local language for personal interactions and Putonghua for official interactions. From there it is a small leap to English for professional interactions. Recently when in Beijing I visited a multinational engineering company, German-owned even, but the official language at work was English. It was amazing to see rooms full of Chinese engineers, most who had never been out of China, all using English to talk to each other at work. It certainly strengthened my understanding of the way English was perceived as a professional tool, no different in some ways from switching among c++, php, html, or java.

2. Our skewed view: My guess is that the type of person who is interested in this blog represents a minority. No doubt, most of the world probably confronts mono-lingual English speakers who assume and demand English for all communication. Our frustration with people who want to speak English with us is most likely counterbalanced with a frustrated world that feels obligated to speak English, even when they feel inadequate in doing so.

3. John asked if my experience in Latin America (with Spanish and Portuguese) was similar to his in China with Chinese. The short answer is no, not really. Indeed I have run across people who insist on practicing English with me, and from a professional end English is everywhere, but the aggressive power struggle seems less in Latin America. My guess as to why… well, first I believe that Latin Americans think that English speakers who do not speak Spanish are just unmotivated or lazy, people who could learn it if they really wanted to. On the other hand, Chinese think of their language as “more difficult”. Deep down they must think that it’s easier for them to learn English than it is for ‘us’ to learn Chinese. Add that to the items mentioned by all of these blog comments, and we see that despite John’s cool proficiency charts, language proficiency is only part of choosing which language is used.

Really interesting answers. Thanks, Dr. Kelm! (For more of Dr. Kelm’s observations, please visit his blog.)

Thank you also to all the readers that pitched in and shared your own observations. You’re certainly correct in that there are way more factors at play than I brought up in the original post. It’s been enlightening bringing it all together from so many different perspectives.

18

May 2010Language Power Struggles

The idea of the “linguistic power struggle” is one I’ve been dealing with and thinking about for a long time. I’ve made some attempts to find scholarly research on the subject, looking into discourse analysis (which is often concerned with power), expectancy violations theory, and communication accommodation theory, but so far I’ve turned up very little (even outside of Wikipedia!). Thus the discussion which follows will be mostly descriptive and anecdotal, but will raise more questions than it answers.

First, a typical example of the language power struggle. The dialog below is taken from a ChinesePod lesson aptly titled Language Power Struggle. I directed the creation of this fictional dialog two years ago, drawing on my own real experiences and those of other friends in China. The content in square brackets [like this] is a translation of the original Chinese. Note that the Chinese person speaks mostly English, while the American speaks only Chinese.

American: [Hello, can I sit here?]

Chinese: Sure, nice to meet you.

American: [I’m also really glad to meet you.]

Chinese: Your Chinese is very good.

American: [Not at all!]

Chinese: How long have you been to China?

American: [I’ve been in China for more than two years. I’m studying Chinese.]

Chinese: Oh, you are learning Chinese?

American: [I want to work in China, so I need to learn Chinese.]

Chinese: Oh. I think Chinese is very difficult for you. How do you feel this bar?

American: [It’s not bad. It’s just that nobody will speak Chinese with me, so I’m a little disappointed.]

Chinese: Ha ha! You are very serious!

American: [Because I want to practice more, so that I can learn Chinese more quickly.]

Chinese: I want to practice English. In Chinese, we say “[learn from each other]”, you know?

American: [I know. But in China we should be speaking Chinese.]

Chinese: I like talking English with you.

American: [Heh heh, then you should go to America. I came to China just to learn Chinese.]

Chinese: I want to go to America. Let’s be friends. Can you give me your mobile number?

American: [Sorry, I’ve got to go.]

The root of the conflict is quite clear: the American guy wants to speak Chinese, while the Chinese guy wants to speak English. There are quite a few issues contained within this small dialog, though. Below I’ll get into more details.

12

May 2010The Challenges Chinese Teachers Face in the USA

The worldwide boom in Chinese study has resulted in a greater demand for Chinese teachers. China is the natural supply, and thus the Chinese government is working hard to train teachers and send them abroad to teach. I’ve heard from numerous sources (including people in the Hanban, an organization which oversees the governments efforts at teaching the world Chinese) that schools are often disappointed with the Chinese teachers sent to them. American schools feel that while the teachers may know about the Chinese language, they are much too traditional in their teaching styles. They just don’t connect with American students very well.

It was interesting, then, to get the other side of the story. ChinaGeeks recently wrote about Teaching Chinese (and China) in the United States, and linked to a great New York Times article: Guest-Teaching Chinese, and Learning America. C. Custer makes some great observations, and his article is well worth a read.

Reading the NYTimes article, Ms. Zheng’s disappointment and frustration is palpable. Clearly, culture is a huge issue; the challenges faced cannot be explained away by outdated teaching methodologies.

> Still, Ms. Zheng said she believed that teachers got little respect in America.

> “This country doesn’t value teachers, and that upsets me,” she said. “Teachers don’t earn much, and this country worships making money. In China, teachers don’t earn a lot either, but it’s a very honorable career.”

And yes, there are also a few ironies in this article that anyone familiar with China will appreciate.

10

May 2010好久没写……

前阵子有几个朋友问我:为什么中文博客不写了?没错,我很久没写,而且最近的几篇都写得很简单,很短。

其实,我最初开始写中文博客的动机是:(1)锻炼写作,(2)多跟中国读者沟通交流。2005年,我初到华东师范大学读研,每个科目的老师在学期末都会要求我写论文。当时觉得写学术论文是个很大的挑战,每次都要花大量的时间才能写出看的过去的论文。(还好有中国朋友帮我修改!)后来,我渐渐觉得自己写课程论文不是那么绞尽脑汁的事了,可是此时却已经要开始准备写硕士论文了。这个挑战更大!

于是我就停止写博客了。当时的我已经受够了“锻炼写作”的乐趣了。毕业以后,由于一直要写论文,我中文已经写腻了,所以也就不想继续写中文博客了。

从毕业到现在,时间已经有两年了。这两年内我买了PS3,重新变成了游戏狂,还开了自己的公司。我想我应该休息放松够了,继而又想“锻炼写作,多跟中国读者沟通交流”了。

喂?有人还在关注我的博客吗?真是忽视你们了。但我觉得很多事情还是“放假比辞职好”。

10

May 2010Fetion Integrates SMS Text Messaging with the PC

The idea of being able to send or receive cell phone text messages on a computer is not a new one, but this Chinese software called “Fetion” (飞信 in Chinese, literally, “flying letter”) is new to me. In a recent AllSet Learning teacher training session, we were discussing various types of technology for learning, including ChinesePod, Anki, and Skritter, when 飞信 came up (weird English name: “Fetion”).

For now, Fetion is PC only, although it also has mobile versions. Its “smartphone” version is aimed at Windows Mobile users, not Android or iPhone users. This all makes a lot of sense if Fetion is targeting a younger Chinese demographic rather than professionals.

For now, Fetion is PC only, although it also has mobile versions. Its “smartphone” version is aimed at Windows Mobile users, not Android or iPhone users. This all makes a lot of sense if Fetion is targeting a younger Chinese demographic rather than professionals.

Fetion mixes social networking properties with communications management properties. One of the benefits it boasts is the ability to store all of your text messages offline on your computer (which Google Voice is currently doing in the US, but in the cloud). Here are the features listed on the Fetion website’s 特性 page:

– A multi-platform system means you’re always reachable

– Free text messaging

– Super-cheap rates for group voice chat

– File-sharing

– Anti-harassment security functionality

– 24/7 customer service

I’ve got to say, this doesn’t seem especially impressive; this technology has been around for a while. It seems that Fetion has caught on with a sizable userbase, however. I’m curious how far it will go.

Have you used Fetion? What are your experiences with it? Is it useful? Do any of your Chinese friends use 飞信?

04

May 2010Shanghai Sculpture Park is pretty awesome

OK, so its name isn’t terribly appealing, its logo is questionable, and it doesn’t even seem to have a website, but Shanghai Sculpture Park (上海月湖雕塑公园) impressed me. At a time when everyone else was heading to the Expo grounds, my wife and I, together with a few friends and our dogs, headed to the Sheshan (佘山) area outside Shanghai, where Shanghai Sculpture Park is located.

OK, so what is cool about this park? Here are some reasons I liked it:

1. You can take your dog. You actually have to buy a ticket for your dog (it’s 30 RMB), but there aren’t many places in Shanghai you can legally take your dog. Most people in the park seemed comfortable with dogs roaming around, and the whole place was quite clean (no doggy “land mines”). It seems to me this is “dog park” done right.

2. The place is huge. We stayed in a small area of the park, but it’s really quite big [map link]. I’m sure there were a lot of people there, but since they were so spread out, it didn’t seem crowded at all.

3. Giant bouncy hills! OK, this is a little hard to explain, and I’d never seen these anywhere before. But one of the attractions is this cross between a cluster of hills, an air-filled moonwalk, and a trampoline. It was a ton of fun. It was a great place for someone even as tall and goofy as me to attempt front flips, although I had to be sort of careful, because as badass as a flying trampoline head-butt is, I doubt it would be appreciated by the little 5-year-old tykes roaming around (or their parents). Pictures below.

Does anyone know what these are called? I think I remember seeing the word “Fuma” on the sign, and this Chinese BBS thread uses the term 大型弹性球 (“giant bouncy sphere”). Anyway, I highly recommend it… the bouncing and the hills make for a really fun combination.

The park also has those things I once referred to as “hamster balls on water.” It looks like they used to have the spherical kind, but now they use a cylindrical kind. This appear to be a bit more stable, but honestly they look much less fun. Wasn’t the whole point that you couldn’t stay on your feet for longer than one second before you fell over thrashing and sent your ball splashing out across the water? The new cylindrical ones are also pictured in this Chinese BBS thread.

A few more things I should mention on the con side…

1. Shanghai Sculpure Park is a bit expensive. The normal price is 120 RMB per adult. Tickets were sold at a discount for 80 RMB each over the vacation. We spent over 300 RMB for a Chinese-style DIY BBQ lunch. On the pro side, though, the high price means it won’t be too crowded (unlike certain Expos I know).

2. The park closes at 5pm. Why so early?? I have no idea. It’s a bit of a bummer.

3. It’s all the way out in Sheshan. Yes, it’s somewhat far. It’s actually right next to the new Shanghai amusement park, Shanghai Happy Valley (欢乐谷). There’s just more space out there.

4. If you spend too long on the giant bouncy hills in your bare feet, you might just develop huge blisters on your toes. Yes, I can personally attest to the veracity of this statement. You really don’t want me to show you.

If you make it out to Shanghai Sculpture Park (上海月湖雕塑公园), let me know what you think.

30

Apr 2010The Calm before the Expo

The Shanghai 2010 World Expo officially kicks off tomorrow. It would be an understatement to say that “Shanghai has been hyping the Expo a lot.” I’ve been taking pictures of various Haibao sightings and a few other Expo-related scenes over the past few months, but it’s finally all coming to a head.

For all the hype that’s been building up, though, there’s been at least as much cause for concern. I’m getting reports from multiple sources that the Expo is disorganized, that it’s a mess, that it’s chaotic, that it will take a miracle for it to not be a disaster. These latest Chinglish pictures don’t exactly inspire confidence that it will be a “world-class event.” Then again, the Chinese do have a way of pulling things off at the last minute. I don’t want the Expo to be an epic fail, but it could certainly happen.

Either way, it’s going to be interesting.

28

Apr 2010Deconstructing the Chinese Character Creativity of Japan

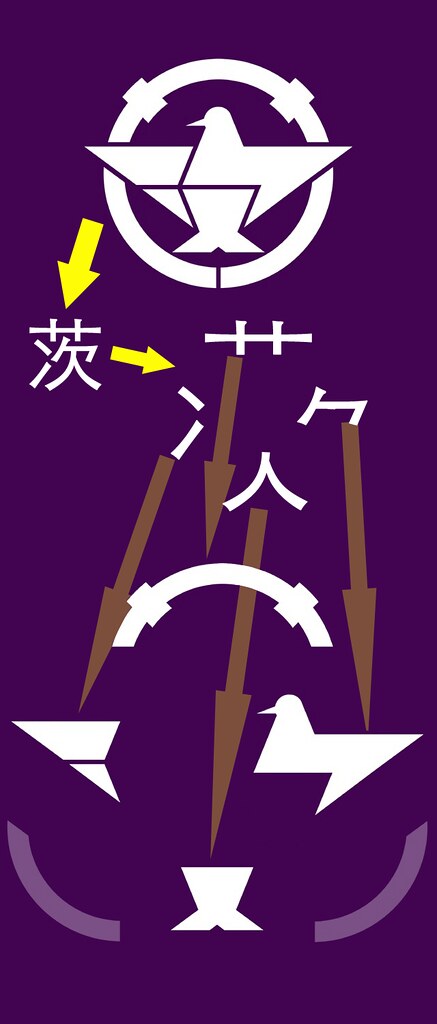

Pink Tentacle recently did a post showcasing Japanese town logos which make prominent use of kanji (Chinese characters in the Japanese written language). These designs totally blew my mind. I love seeing creative manipulation of Chinese characters, so this stuff was pure gold.

Be warned, though; some of these are a bit hard to make out if (1) you don’t know what character(s) you’re supposed to be looking at, and (2) you don’t have significant experience with Chinese characters. Below I’ll explain a few of the designs to make them a bit more accessible.

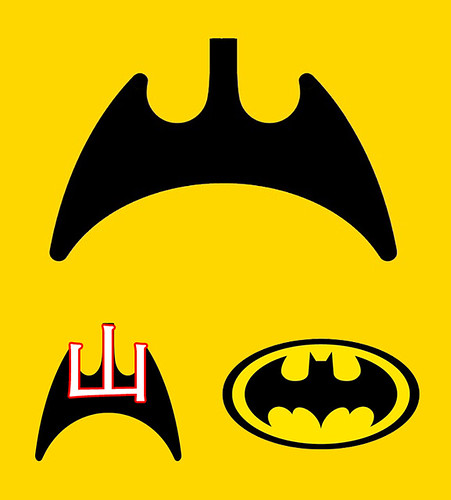

I’ll start easy. This one is cool because it’s not hard to make out, and it has an easily recognized source of inspiration:

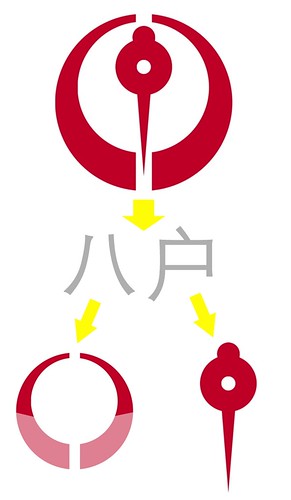

This next one is actually two characters, but both are fairly easy to recognize (they’re just a bit chubbier than usual), and they have the added benefit of resembling a Japanese robot! Nice.

Two characters again (八 returns!), but this time a decidedly asymmetrical character is forced into a symmetrical design, with interesting results.

Now we’re getting a little crazy. This very stylized logo turns a line into a circle and a box into a triangle. It takes a bit of mind-bending to see it.

This one is probably my favorite (overlooking any similarity to the logos of past fascist regimes).

So it turns out learning character components can have interesting applications after all. Be sure to check out all the other logos on Pink Tentacle. There are plenty more good ones.

26

Apr 2010New Online Chinese Resources Links

I figured it was about time I set up a page with links to the Chinese learning resources I personally find most valuable and regularly use. So it’s up: Online Chinese Resources.

A few notes:

– I work for ChinesePod and think it’s great, so yeah, I’m going to recommend it. This should not be a big surprise. I’m aware of quite a few podcast alternatives, and I’ve listened to a few, but I have very limited actual experience with them.

– The list is not exhaustive; there are plenty of monstrous ones out there, and the problem is that they’re all way too long. This one is pretty short, and based on my own experience, which is what makes it useful.

– I am open to suggestions, but I won’t add anything until I’ve had a chance to check it out and spend enough time with it to decide it’s a must-have resource.

I’ll be updating the list pretty regularly, but I intend to keep it brief.

21

Apr 20102, 3, 4

I like the building numbers at 映巷创意工场:

If you don’t recognize the numbers, check my number character variants post. They are: 贰 (2), 叁 (3), 肆 (4).

Building #4 is where Xindanwei is. This Friday at 4pm I’m giving a talk there called Language Power Struggles in Shanghai. Feel free to stop in! I’ll post notes on it here later.

18

Apr 2010The Wall Street Journal on Chinese Humor

I’ve been interested in Chinese humor for a while. Most recently, I’ve written about a few Chinese comics and Shanghainese stand-up comedian Zhou Libo. So I was quite interested in the Wall Street Journal’s take, which is initially about Chinese comedian Joe Wong. Apparently Joe Wong’s comedy works in the U.S. but not in China. It’s not your typical cross-cultural story.

This is the part which caught my attention (emphasis mine):

Younger audiences are starting to warm to the stand-up style, with a Chinese twist. There are footnotes: after the punch line comes an explanation of why it’s funny.

In Shanghai, Zhou Libo’s stand-up show has become a top event. His repertoire spans global warming, growing up poor and, that perennial crowd-pleaser, China’s emergence as a global economic power.

He jokes about China’s massive purchases of U.S. Treasury bonds: “I am really confused about why a poor guy lends money to the rich. We should just divide the money amongst ourselves,” he says. “But on a second thought, each of us would only get a couple of dollars!” Then Mr. Zhou adds: “Because the population is so big.”

This is one of the observations I made in 2004 in a post titled When Humor Runs Aground, in which I give an example of a Chinese joke, with the punchline and also the “post-punchline explanation.”

I’d be interesting in seeing more examples of this “post-punchline explanation.” From a sociolinguistic perspective, I wonder how universal it is, and if it follows certain rules. More examples are welcome!

16

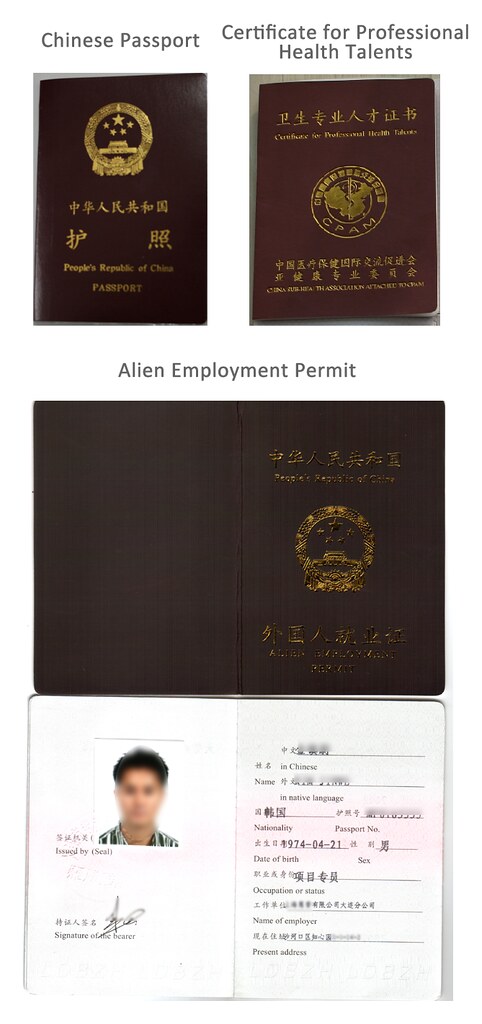

Apr 2010Gag Chinese Documents (very official-looking!)

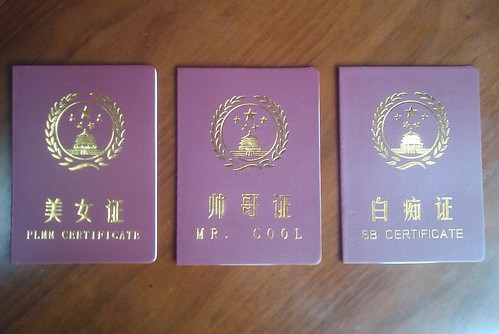

I was quite amused to stumble upon a whole array of fake (but humorous) Chinese documents last weekend. The documents adopt the official style of Chinese 证书 (official documents), but the names are a lot more fun. Here are the three I bought (for 5 RMB each):

The three types of documents above, left to right, are:

– 美女证 (Babe Certificate); “PLMM” stands for “漂亮妹妹” (pretty girl)

– 帅哥证 (Cute Guy Certificate)

– 白痴证 (Moron Certificate); “SB” stands for “傻屄” which I’ll politely translate as “dumbass”

There were at least 10 different types, including things like “World’s Best Mom,” “World’s Best Dad,” “Certified Genius,” “Certified Virgin,” etc.

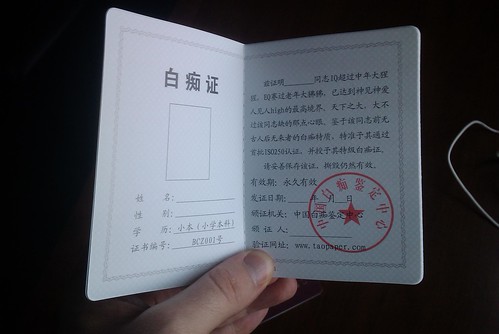

The insides even look official, with space for a photo:

For comparison purposes, here are some real Chinese certificates, collected from the internet:

I can’t imagine the government will be particularly happy about these things, especially with the Expo looming. I wouldn’t be surprised if these became scarce really quickly (especially in Shanghai).

Looks like my Flickr photos aren’t showing up for the time being; you can thank the GFW for that. The photos are viewable via proxy.

14

Apr 2010The Big Bang Theory: Sheldon’s Chinese

A few weeks ago, a series of clips from The Big Bang Theory, Season 1, Episode 17 became popular on various Chinese sites. In the episode, brainy theoretical physicist Sheldon says he has decided to learn Mandarin because:

> I believe the Szechuan Palace has been passing off orange chicken as tangerine chicken, and I intend to confront them.

Here’s the clip (on Tudou):

To someone who knows no Chinese, this episode works fine. However, native speakers of Mandarin will have trouble following a lot of what Sheldon is trying to say. Although most of the first scene would be easy to follow, a combination of inaccurate pronunciation and bizarre word choices in later scenes make the subtitles a necessity for even native speakers of Mandarin. (I forced my wife to watch this clip with the subtitles covered up, and she could only understand a few of the lines, even listening multiple times. You can also find more than one “what the heck is he saying??” conversations on the Chinese internet, like this one.) The Chinese clip adds Chinese subtitles, but some of them are inaccurate. The play-by-play is below.

13

Apr 2010An American Master’s in Education, in Shanghai

Following a post entitled Why China for Grad School?, I interviewed Zachary Franklin about his half-English, half-Chinese economics master’s program. This time I interview Micah Sittig, who is earning a master’s in education through a quite different program in Shanghai.

John: Can you tell me what graduate degree you’re working on?

Micah: I’m working toward a Master’s in Education from the University of Oklahoma (OU). I’ve been teaching math and science in the English division of a private school on the outskirts of Shanghai for four years now, and this is the first time that the school has teamed up with a university to offer this kind of opportunity. Naturally I jumped at the chance because it means being able to stay in China and earn what I feel is a US-quality advanced degree.

John: What kind of program is it? Is it meant for foreigners?

Micah: It’s an intensive, two-year master’s offered by the University of Oklahoma. The College of Education sends professors to Shanghai during vacations for one week of class, 62 hours total, including a practicum that we’re just finishing now. It’s a general Master’s in Education that is meant for teachers from preschool up through high school, and includes courses like Intro to Teaching and Learning, Educational Psychology, Theory and Research in Education, and Instructional Technology. Enrollment was not limited to foreigners, but only 3 out of 15 students are native Chinese, probably because the entire program is being conducted in English. I suspect that some of the professors were mentally prepared to teach a majority Chinese class, but that doesn’t mean they lowered the pace or difficulty of the material.

John: In terms of course content and professors, how does your program compare to comparable programs in the States?

Micah: In theory the content is offered at the same level as it was in the United States. Some professors have tried to get our input from a Chinese perspective, but the majority of the students are from the US or other nationalities, and the Chinese students either don’t participate much in discussions or have a hard time bridging the cultural gap with the professors. The Tech Ed class also had a heavily modified syllabus since many online tools aren’t available in China; thanks a lot, GFW! The professors are what you’d expect anywhere—some good, some bad—but overall I’ve been very happy with the caliber of the instructors and the level of instruction.

John: Education in China has long been the focus of various debates. Has Chinese-style education impacted the content of your program?

Micah: Due to the nature of the program, it hasn’t been impacted by Chinese-style education. However, my wife Jodi is concurrently studying for a second undergrad degree in early childhood education at ECNU and what has been interesting is comparing the teaching style and content in courses or topics that we’ve both studied. Jodi’s classes, of which I’ve been able to sit in on a couple, place a much greater emphasis on content than on practice. One particularly bad teacher would just spend the lecture talking through the text and pointing out facts or passages that test questions would be taken from; it was a textbook case of teaching to the test. Add to that the Chinese reverence for (their 5000 years of) history and you have a lot of content to cover. On the other hand, I felt like my program emphasizes practice over content, sometimes to a fault. In some classes the professors spend a lot of time talking about how we feel and what we do in our classrooms, and neglect to give us a framework on which to organize our ideas. As you might expect, the teacher with the most organized notes and Powerpoints was the one prof of Korean heritage.

John: Can you share any information with readers interested in the program?

Micah: The first OU cohort will be graduating this summer and a second cohort is being considered that would start classes early next year. Please contact me if you are interested in joining the next cohort or just want more details, and I will put you in touch with the program coordinator at my school. [SEE UPDATE BELOW]

Micah’s website has his contact information, as well as links to his blog and his Twitter account.

July 16, 2018 Update

Micah has written to let me know that this program through Oklahoma University is no longer being offered in Shanghai, but he recommends the following programs as alternatives for international educators looking to upgrade their skills or become certified in the US:

- TeacherReady, offering distance certification in Florida.

- The College of New Jersey Off-Site Graduate Programs, offering MAs and certification in New Jersey.

- Western Governors University, offering undergrad/grad teaching degrees leading to certification.

08

Apr 2010Xindanwei Chit-Chat Event #1

Tomorrow, Friday April 9th, at 4:30pm Xindanwei is having a “Chit-Chat.” It’ll be a mix of Chinese and foreigners, and the guest speaker is Andrea Pan, AKA @popoever, who will be talking about social media (quite possibly mostly in Chinese). Admission is free.

I’ve invited a few Shanghai blogger friends already. It’ll be a good chance to meet up and chat in a relaxed setting, and to check out Xindanwei, the co-working community where my new business AllSet Learning is also based.

06

Apr 2010Crazy Heart’s Fallin’ and Flyin’: a Chinese Translation

I saw Crazy Heart the other day, and to my surprise, I rather liked it. While I can certainly understand my wife’s view that it was “boring” and that “nothing really happens” in it, I found it enjoyable.

Perhaps what I enjoyed the most was seeing Jeff Bridges (who will always be “the dude” in the Big Lebowski to me) and Colin Farrell play American country singers and actually sing their own songs. I was impressed. Colin Farrell is Irish!

Not only that, but several days later I’m finding that a few of those songs are still stuck in my head. I tried to find them online, but it’s a bit difficult. I turned to a Youku video of the entire movie. The Jeff Bridges / Colin Farrell “Fallin’ and Flyin'” duet begins at 47:30 in that video. Watching this scene for the second time, I paid much more attention to the Chinese translation of the lyrics (provided in full at the end of this post), and found a few interesting points.

The opening few lines were done very nicely, both in terms of reproduction of the parallel construction, as well as in rhythm. These lines match the rhythm of the song perfectly, meaning they could even be sung in translation.

> I was goin’ where I shouldn’t go

我去不该去的地

> Seein’ who I shouldn’t see

看到不该看的人

> Doin’ what I shouldn’t do

做了不该做的事

> And bein’ who I shouldn’t be

成了不该成的人

It’s always interesting to see translations of the verb “to be,” as in “bein’ who I shouldn’t be,” and this one was done well.

Unfortunately, after this the Chinese translation breaks the rhythm and gets way too long for the English:

> A little voice told me it’s all wrong

有个微弱的声音对我说 这一切都不对

> Another voice told me it’s all right

另个声音对我说 这一切没关系

What initially caught my attention, though, was the translation of the main chorus:

> It’s funny how fallin’ feels like flyin’

奇怪奇怪 有那么一瞬

> For a little while

感觉堕落好似飞翔

Translating this Chinese translation back into English, it would be something like:

> It’s strange, it’s strange… just for an instant

[Being] fallen felt like flying

The use of the Chinese word 堕落 makes sense; it’s commonly used in phrases like “fallen angel” (堕落天使). The problem is that it means “fallen” and not “falling”; it emphasizes some kind of degeneration or “Fall from grace” rather than a physical fall. So whereas “fallin’ feels like flyin'” can be understood on both the literal level (like skydiving, maybe) as well as a figurative level, this Chinese translation chucks the literal interpretation out the window. I wonder whether both meanings were just too difficult to translate into Chinese, or if perhaps the translator heard “fallen” rather than “fallin’.”

Also, there’s the use of 一瞬, which means “an instant.” “For a little while” is certainly not an “instant”… especially when this song represents the main character’s own life, and he’s been “falling” for decades, perhaps.

The translations of these lines made me smile:

> Never see it comin’ till it’s gone

失去后才知道珍惜

> It all happens for a reason, even when it’s wrong

就算错事也有因

> Especially when it’s wrong

尤其是错事

The “never see it comin’ till it’s gone” sounds very country, very American, and rather cliché to me, and yet “失去后才知道珍惜” sounds so typically Chinese, the kind of line you hear in countless Chinese love songs. And yet, it’s a pretty accurate translation. Well done.

I was also amused by the use of 错事 for “when it’s wrong.” The Chinese language likes to bring in 事 when it can. It works.

Overall, the translation is pretty solid. With a little more work, I think it could even be sung. I’d be interested in hearing other thoughts on this translation into Chinese (尤其想知道中国朋友的看法!).

05

Apr 2010Chinese Character Creations for Modern Times

You’ll have to be following Chinese internet memes to get all of these, but there are some clever ones:

The character creations are fusings of various characters. They are:

> Row 1, left: 亚克西

> Row 1, right: 贵国

> Row 2, left: 代表

> Row 2, right: 屁民

> Row 3, left: 党中央

> Row 3, right: 五毛

I won’t comment on the meanings of these internet memes because I’m not very familiar with all of them, and anyway, this is an apolitical blog. 🙂

Previous character creations on Sinosplice: Character Creations, Chinese Characters for Christmas

01

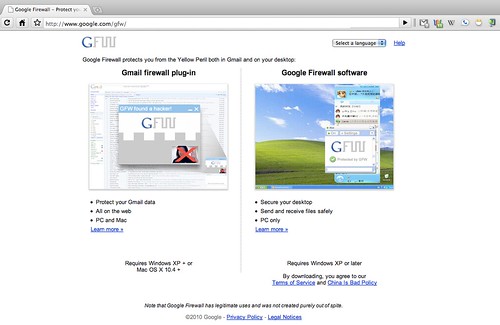

Apr 2010Google Strikes Back with New Firewall Software

A friend of mine works at Google headquarters in Shanghai. He said Google Shanghai has been working on a new type of firewall software for a long time, uncertain of the correct time to release it. He shared with me this screenshot from Google, however:

Apparently the software has two forms: a Gmail plugin to keep your account secure from Chinese hackers (AKA the “human rights activist version”), and a desktop application which filters out requests to or from Chinese IP addresses (especially Shaoxing).

It will be interesting to see if Google actually releases this “GFW” software. (I’m guessing if they do, they’ll redesign that ugly logo…)

I’ve closed comments for this post because I promised to protect my Google friend’s anonymity and the comments are a bit of a risk.

April 2 Update: OK, the joke is over and comments are now open. This was my April Fool’s Day hoax. It was fairly obvious if you looked at the full size image (or compare to this page), but it appears most people did not. Anyway, now I will return to being fully serious about the Google issue, because I seriously don’t want Google to be completely cut off from China!

28

Mar 2010Introducing AllSet Learning

I’m excited to finally publicly announce a project I’ve been working on since last year. I’ve started a new company called AllSet Learning. It’s a learning consultancy focused specifically on solving the problems faced by expats in Shanghai trying to learn Mandarin.

I’m especially happy that in this new venture I have the support of Praxis Language CEO, Hank Horkoff. Hank is one of the most driven entrepreneurs I know, and he has had no small influence on my own decision to start a company. So the good thing is that I will continue to work on the academics and podcast recordings at ChinesePod (which I love), and also have my own operation. AllSet Learning will not produce its own content, and will emphasize face-to-face (offline) learning, so it will complement rather than compete with Praxis Language’s products. Over the next year, AllSet Learning will also be the first official ChinesePod Partner as ChinesePod opens up its resources to third parties more.

In this new business I’m really looking forward to talking to individuals about their own specific problems learning Chinese, and really getting into the nitty-gritty of it. ChinesePod is the best online resource for practical study material in Mandarin, but online discussion is just not the same level of personal interaction that working as a consultant on the streets of Shanghai makes possible (and yes, I am going to take it to the streets!).

The AllSet Learning office is located at Xindanwei, a really cool, creative community which has hosted events like Barcamp and Dorkbot, and regularly has interesting characters like Isaac Mao passing through.

I’ll mention developments at AllSet Learning here from time to time. I have a lot planned in terms of offline events and research. If you’re interested, please visit the website, and don’t hesitate to get in touch.