14

Jan 2010Worry about the Internet in China

If you’re not in China, it may be hard to imagine the extent of the worry caused by Google’s recent announcement that it may just pack up and leave China. Sure, you can analyze the political and financial angles, but for most of us, this recent news forces our minds to leap straight to the worst-case scenario that will affect us personally: what if all Google services get blocked in China?

Many (including this Chinese language summary of the situation) are concluding that using a VPN might just have to become an essential “always-on” part of using the Internet in China. My fear is that if that day comes and VPN usage becomes so widespread, it might not be long before that method too is struck down by new GFW technology. I’m really afraid of being stuck in that information void.

It’s not just about one big company operating in China. It’s about how in recent years, various internet services have made us feel much more connected to our loved ones half a world away. It’s about how the internet is becoming such an integral part of our lives, through email, through IM, through social services, through smartphones… and wanting to be a part of that progress. No company is more key to that progress than Google.

A Chinese friend of mine recently admitted to me what I didn’t want to say myself: “if they go so far as to block all Google services in China, I don’t even want to stay here anymore.”

This is how deep the worry runs for many of us.

If you’re not up on the situation, I recommend these articles:

– Google and China: superpower standoff (a good blog post roundup on the Guardian)

– Earth-shattering news and a faked interview (Danwei’s angle)

– Google’s China Stance: More about Business than Thwarting Evil (TechCrunch)

– Soul Searching: Google’s position on China might be many things, but moral it is not (TechCrunch)

– Google v. Baidu: It’s Not Just about China (TechCrunch)

– The impact of Google’s bold move

12

Jan 2010Cosmetic Surgery Culture

ChinesePod co-worker Jenny had occasion to visit the plastic surgeon’s office recently, and she took away some interesting (although not terribly surprising) insights:

> 1. Most popular form of plastic surgery in China: an even divide between all-time favorite double eyelid operation (双眼皮/shuang1yan3pi2) and new comer face-slimming injection (瘦脸针/shou4lian3zhen1).(Note, many Asians are born with single eye lid, but double eye lids are considered beautiful. We are also obsessed with a small face. My take is that Asian faces tend to be flatter (hence bigger). I don’t know what’s ugly about that, but there is an industry dedicated to making one’s face smaller, everything from lotion to plastic surgery).

> 2. The consumers: girls in their 20’s top the list. The aforementioned operations were monopolized by these girls. There were literally 5 girls coming in for one of those treatment every hour.

See her blog post for the rest.

06

Jan 2010Avatar IMAX 3D Tickets Selling Well in Shanghai

Peace Cinema (和平影都) in Raffles City (People’s Square) is the place to see Avatar (阿凡达) in IMAX 3D in Shanghai, but it’s still hard to get tickets, days after the Sunday midnight opening. I went tonight, hoping to pick up a pair of tickets for sometime in the next week, but the theater only sells two days in advance, and all popular times were sold out. You can see the crowd in the picture below. The crowd never got too big, because everyone kept showing up, finding out it was sold out, and then leaving unhappily.

Tickets there range from 30 RMB (non-IMAX) to 50 RMB (IMAX, morning), to 150 RMB (IMAX, prime time on weekends). The soundtracks are all English, with Chinese subtitles. The theater’s (?) website has the price list for the current day.

Avatar has been out on DVD in the streets of Shanghai for a while, but I’m still patiently waiting to experience IMAX 3D for the first time (eventually).

Jan. 7 UPDATE: A friend of my wife offered to buy tickets for us. She showed up at 7:30am to get in line. The theater opens at 9am. When she arrived, there were already 200-300 people in line, some of whom had been there since 4am. Still, with so many showings every day, and a pretty decent capacity, you’d think that person number 300 could still get tickets. No dice. Everyone was buying up lots of tickets, so the theater was sold out of Avatar 3D IMAX tickets by the time our friend’s turn came.

I just found out that the theater is raising prices to 180 RMB per ticket next week. Suddenly I’m losing some of my enthusiasm for Avatar in Shanghai…

Jan. 11 UPDATE: Over the weekend the price rose again from 180 RMB to 200 RMB, caused a furor, and then was changed back to 150. Also, the sale of tickets was opened up for all of January, after which all IMAX 3D tickets promptly sold out. (I’m OK with this; I gave up on IMAX and watched it in regular 3D yesterday. It was awesome.)

04

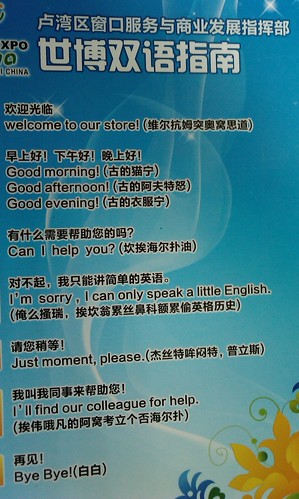

Jan 2010Chinese for English Pronunciation (Shanghai World Expo Edition)

This certainly isn’t the first time that Chinese characters have been used as a guide for pronunciation of English words, but it’s the most recent example I’ve seen, related to Shanghai’s World Expo. Here’s the “世博双语指南” (World Expo Bilingual Guide):

And here’s a text transcription of the content:

> 欢迎光临

welcome to our store! (维尔抗姆突奥窝思道)

> 早上好!下午好!晚上好!

Good morning! (古的猫宁)

Good afternoon! (古的阿夫特怒)

Good evening! (古的衣服宁)

> 有什么需要帮助您的吗?

Can I help you? (坎埃海尔扑油?)

> 对不起,我只能讲简单的英语。

I’m sorry, I can only speak a little English.

(俺么搔瑞,埃坎翁累思鼻科额累偷英格历史)

> 请您稍等!

Just a moment, please. (杰丝特哞闷特,普立斯!)

> 我叫我同事来帮助您!

I’ll find our colleague for help.

(埃伟哦凡的阿窝考立个否海尔扑!)

> 再见!

Bye Bye! (白白!)

And just in case all those “nonsense characters” were too much for you, here are some randomly selected pinyin transliterations. See if you can figure out the English original:

– Āi wěio fánde āwō kǎolìgè fǒu hǎiěrpū!

– Gǔde āfūtènù

– Wéiěrkàngmǔ tū àowō sīdào

– Ǎnme sāoruì, āi kǎn wēnglèi sībíkē é lèitōu Yīnggèlìshǐ.

– Kǎn āi hǎiěrpū yóu?

Fun stuff.

29

Dec 2009I'm a dinosaur, yo

In the tradition of St. Seiya and Benny Lava, here’s a great Japanese music video subtitled in hilarious, (mostly) non-sensical Mandarin:

These lyrics are a bit too non-sensical to warrant a translation into English, but they’re still pretty funny in Chinese. To give you a taste, the first line is “我是恐龙哟” [I’m a dinosaur, yo].

23

Dec 2009Classic Chinese Christmas Song Links

Every year around Christmastime, my “Christmas Songs in Chinese” blog post from 2006 gets a lot of action. I’ve been seeing a lot of requests there for lyrics, and I tried to help out with that, but I found the Chinese versions of these Christmas songs’ lyrics surprisingly difficult to track down. If anyone can offer links to those lyrics, it would be appreciated by many.

Anyway, you may enjoy these Sinosplice Christmas music posts from the archive:

– Christmas Songs in Chinese (13 MP3s)

– Ding Ding Dong (hilarious Hakka version MP3)

– Christmas Classics in Cantonese (the song link is still good, but the Flash links below are mostly dead now)

– The Christmas Story in Chinese (#005 and #006 in the New Testament)

Photo by Pakueye on Flickr

Merry Christmas!

21

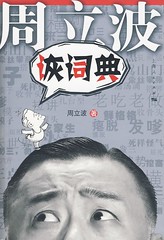

Dec 2009Zhou Libo's New Book: Hui Cidian

Taking advantage of his current popularity, Shanghainese stand-up comedian Zhou Libo (周立波) has swiftly published a book on Shanghainese expressions called 诙词典 (something like “Comedic Dictionary”).

The book isn’t exactly a dictionary, but it groups a whole bunch of Shanghainese expressions by common themes or elements, then explains them entry by entry in Mandarin, followed by a usage example from Zhou Libo’s stand-up acts for each entry.

“Shanghainese” Characters

What’s interesting (and a bit annoying) is that Shanghainese sentences are written out in Chinese characters, and then followed by a Mandarin translation in parentheses. Here’s an example of such a sentence:

> “伊迪句闲话结棍,讲得来我闷脱了。(他这句话厉害,说得我一下子说不出话来了)”

> [Translation: “That remark of his was scathing. I had no comeback for that.”]

The book is peppered with sentences like this, and as a learner, I have some issues with them:

1. If you read the Shanghainese sentences according to their Mandarin readings, they sound ridiculous and make no sense (a lot of the time) in either Mandarin or Shanghainese.

2. Unless you’re Shanghainese, you will have no clue as to how to pronounce the Shanghainese words in the sentences properly (so what’s the point?).

3. I find myself really wondering how the editors chose the characters they used to represent the Shanghainese words.

To point #3 above, I know there are cases where the “correct character” can be “deduced” due to Shanghainese’s similarities to Mandarin. To use the example above, the Shanghainese “闷脱” can be rendered in Mandarin as “闷掉.” Then why 脱 instead of 掉? Well, 掉 has a different pronunciation in Shanghainese, and it’s not used in the same way as it is in Mandarin. The 脱 in “闷脱,” however, in Shanghainese is the same 脱 as in “脱衣服” in Mandarin (which is “脱衣裳” in Shanghainese). It seems like this game of “chasing the characters” from Mandarin to Shanghainese might be ultimately circular in some cases, but I can’t really judge.

The other point is that some of Shanghainese’s basic function words, pronouns, and other common words don’t correspond to Mandarin’s at all, and the characters used certainly seem like standard transliterations. An example from the sentence above would be the Shanghainese “迪” standing in for Mandarin’s “这,” or (not from above), the Shanghainese “格” for Mandarin’s “的.”

So how do you know which characters are “deductions” (these are kind of cool and can point to interesting historical changes in language), and which ones are mere transliterations? Well, research would help. I don’t have much time these days for such an endeavor, but I do know some Shanghainese professors of Chinese at East China Normal University who could point me to the right resources.

Shanghainese Romanization

Lack of a standard romanization system is a problem that has plagued students of Shanghainese forever. Some favor IPA, but most find it a bit too cryptic. The problem is there is still no clearly superior solution that has become standard.

Zhou Libo’s book doesn’t make any headway in the romanization department. Headwords are given a “Shanghainese pronunciation” using a sort of “modified pinyin” with no tones. This is definitely more helpful than nothing, but it’s another reason why this book doesn’t make much of a learner’s resource for Shanghainese. Where the romanization diverges from pinyin, you’re not sure how to pronounce it (“sö” anyone?), and where it matches pinyin, it’s often not really the same as pinyin.

19

Dec 2009Pleco for iPhone is out!

After reviewing the beta version, interviewing Michael Love on the app, and commenting on beta testing progress, I’d be remiss not to note that the Pleco Chinese Dictionary iPhone app is out. And the really great news is that the basic app is free!

A quick intro from the Pleco product information page:

> Go to itunes.com/apps/PlecoChineseDictionary to instantly download the free basic version of Pleco for iPhone / iPod Touch; you can add on more advanced features / dictionaries from right inside of the app, but the basic version is an excellent little dictionary in its own right (and includes the same wonderful search engine as our more advanced software).

If you own an iPhone and you’re studying Chinese, get this app!

17

Dec 2009Default Social Activity: Murder!

It wasn’t until after I’d been in China a while that I started thinking about a culture’s “default social activities.” Friends like to get together, and there’s often no special occasion, so they tend to rely on the defaults. If you’re sports fans or gamers, you might have ritual activities, but most people I knew growing up in Suburbia, USA relied on a small number of default activities:

1. Go to a movie

2. Go to a bar

3. Go to a party

4. Go bowling (or mini-golfing)

After staying in China a while, it took some time to realize that most Chinese people don’t go to movie theaters often, hardly ever go to bars, and don’t really do the party thing. Bowling only happens on rare occasions. China’s “default social activities” list looks more like this:

1. Go to dinner

2. Play cards (or mahjongg)

3. Go to karaoke

4. Play 杀人游戏 (“the murder game”)

It wasn’t until recently that I realized the status and ubiquity of the 杀人游戏 (a game usually known as “mafia” in English). A few years ago I thought it was just a fad, but I just keep hearing about it everywhere, from all kinds of people. It’s just not going away. Recently my friend Frank brought to my attention that some players in China are so fanatical about it that they join clubs (with 6000 members), and even pay to play.

Anyway, if you live in China, definitely give it a try. It’s almost certain that all your young Chinese friends know the game, and you can play it almost anywhere. If you ask me, it’s way better than cards, mahjongg, or karaoke, and if you’re learning Chinese (or your Chinese friends are learning English), it’s good fun practice.

I’m not sure how many versions are played nowadays (it’s been a while since I’ve played), but the Baidu Baike page has an extremely lengthy “version history” with tons of different roles. All you really need to get a game going, though, are the words “杀人游戏.”

15

Dec 2009Bits from Beijing

I just got back from a business trip to Beijing. I was representing ChinesePod at the Hanban’s recent “Exhibitions of Resources of Confucius Institutes and World Languages.” Despite having lived in China for over 9 years, it was my first time in northern China in the winter. Here’s what I noticed:

– Chinese 暖气 (central heating) is awesome. I’m used to winters in Shanghai, to only being warm for short periods of time during the winter, to the floors being freezing for months on end… so I was not prepared for my hotel being “boxers and a t-shirt” warm the whole time. And the floors weren’t cold at all. (Now I also see why visitors from the north are so wimpy here in the winter.)

–  Wow, the former Olympic Village is a desolate ghost town (but the “You and Me” theme song is still playing on a loop there). It’s such a huge space; you’d think that it would be utilized a little better post-Olympics. The exhibition I attended was in the “National Conference Center,” but drivers didn’t even know where that was; when I asked to be taken to the 国家会议中心 (National Conference Center), I was invariably taken to the nearby 国际会议中心 (International Conference Center). I guess even the massive new conference center isn’t getting much use yet.

Wow, the former Olympic Village is a desolate ghost town (but the “You and Me” theme song is still playing on a loop there). It’s such a huge space; you’d think that it would be utilized a little better post-Olympics. The exhibition I attended was in the “National Conference Center,” but drivers didn’t even know where that was; when I asked to be taken to the 国家会议中心 (National Conference Center), I was invariably taken to the nearby 国际会议中心 (International Conference Center). I guess even the massive new conference center isn’t getting much use yet.

–  The world’s largest LED screen at “The Place” is impressive… but it’s kind of sad. That mall doesn’t seem to have a ton of traffic still, and the screen already has more than a few dead pixels. (The screen faces downward, by the way, and it’s only on at night.)

The world’s largest LED screen at “The Place” is impressive… but it’s kind of sad. That mall doesn’t seem to have a ton of traffic still, and the screen already has more than a few dead pixels. (The screen faces downward, by the way, and it’s only on at night.)

–  When I ordered a “Hawaiian pizza” at a cafe, I got a pizza with spam, dragon fruit, banana, apple, and kiwi fruit on it. Yikes.

When I ordered a “Hawaiian pizza” at a cafe, I got a pizza with spam, dragon fruit, banana, apple, and kiwi fruit on it. Yikes.

(Normal blogging to resume soon… Recent spottiness is due largely to lots of time spent on some “new research.”)

08

Dec 2009A Message to Mandarin

One of ChinesePod’s more active and positive users, simonpettersson, recently wrote an amusing Open letter to the Chinese language. Here’s how it starts out:

> You’re afraid, aren’t you, Mandarin? You’re starting to feel it; the cold sweat trickling down your back. You heard I kicked English’s ass already at 12, and you witnessed first hand what I did to French. French is my b*tch now. And I’m coming for you, Mandarin.

> I know you fancy yourself the biggest, meanest language in town. I know you beat the snot out of most anyone who comes to take you on. Hell, you even gave me a sound asswhooping once that caused me to give you space for quite some time. But I’m not like the others. I’m not giving up, and with every day I grow stronger. You ain’t never met anyone like me, Mandarin. And you’re starting to realize it.

The rest of it is on ChinesePod.

I loved this post, and not just because of the “I don’t care if it’s supposed to be difficult” attitude. Simon does a good job of reminding us that learning a language is not just a weekend’s endeavor, and to keep up the fight, you have to play the mental game. You have to psych yourself up. Talking a little trash does some good.

It also reminds me that I’ve got to keep working hard too if I want to someday be able to deliver the kind of merciless asswhooping that Simon describes.

Here’s to asswhoopings!

Related: Why Chinese Is So Damn Hard

02

Dec 2009New Host

I haven’t been posting much lately, but I’ve still been working on this site. I finally chose a new web host so that I can leave DreamHost. The new host is WebFaction, and so far it’s excellent. It’s not quite that simple, though.

WebFaction is excellent because:

– It allows for easy hosting of multiple websites

– It makes its policies on application memory usage completely clear to users (this is the major sin of DreamHost and its ilk)

– It’s fast

– It has affordable dedicated IP solutions (important in case you get blocked by sheer bad luck)

– I wrote the support team on three separate occasions at different times, and each time, they got back to me within 5 minutes. (These weren’t very difficult questions, but still… that’s amazing, coming from DreamHost, which responded in a few hours on good days, in a day on typical days, and NEVER on bad days)

WebFaction is maybe not great for everyone because:

– The control panel seems quite rudimentary after using DreamHost’s, seeing Media Temple’s, and seeing a few others. It really seems quite bare bones. (A few features I asked about were “in development,” but they had other somewhat techy workarounds.)

– The company uses its own unintuitive system for installing “Applications” and pairing them with domains. (I use the word “application” in quotes because not only web apps like WordPress, but also even things like static directories for hosting files count as “applications.”)

The system is actually kind of cool once you get used to it, but it’s definitely not for someone who just wants one simple website. I’ll probably write more about it once I’m fully moved over.

The other way I’ve been spending time on Sinosplice is with a long-overdue redesign. The whole site! More on that later…

22

Nov 2009Updates and Links

Updates:

– Since my GFW Android Market rant, it looks like the Android Market may no longer be blocked. I’ve been able to access it again for the past few days on my HTC Hero here in Shanghai. Not sure if this will last, but it’s certainly a welcome development!

– Pleco for iPhone (beta) just went into Beta 4 testing. Michael Love says this will probably be the last round of testing (but wow, that team does an amazingly thorough job!), so that means it will likely be submitted to Apple for review very soon.

Links:

– Google recently released a pinyin conversion tool on Google Translate, but it’s super primitive. Mark at Pinyin.info details all the ways it sucks (via Dave), but they all boil down to this: the tool simply romanizes characters, without regard for proper spacing, proper punctuation, or multiple character readings that can only be determined with data-informed word segmentation. (Boo, Google! You can do waaayyy better!)

– Google also added a cool-looking new Google Translate Toolkit (via Micah), which looks like the beginnings of competition for translation software like TRADOS (the preferred tool of translator Pete).

– An over-the-top rant on the importance of reading Chinese (via Micah) serves as a good reminder to those of us who might be satisfied with our functional speaking ability and too lazy to improve our literacy (this is definitely me at times!).

– Speaking of reading material, ChinaSMACK recently reminded me that even when you’re too lazy to tackle 老子 or modern thinkers, there’s still less challenging but interesting material to read in Chinese, and reading something is certainly better than nothing.

– Finally, most of us have used character-by-character literal translation as a mnemonic for memorizing certain Chinese vocabulary, but now there’s a blog dedicated to just that, called “those crazy chinese.” “Sweet pee disease,” “hairy hairy balls,” “ear shit”… check it out.

19

Nov 2009Aspect, not Tense

You often hear people saying that Chinese has simple grammar, and the most often cited reason is that “Chinese has no tenses.” It’s true that Chinese verbs do not have tenses, but Chinese grammar does have a formal system for marking aspect. What is aspect? Most English speakers don’t even know.

I’ll quote from the Wikipedia entry on aspect:

In linguistics, the grammatical aspect (sometimes called viewpoint aspect) of a verb defines the temporal flow (or lack thereof) in the described event or state. In English, for example, the present tense sentences “I swim” and “I am swimming” differ in aspect (the first sentence is in what is called the habitual aspect, and the second is in what is called the progressive, or continuous, aspect). The related concept of tense or the temporal situation indicated by an utterance, is typically distinguished from aspect.

So if the temporal situation (tense) of a verb is typically distinguished from aspect, shouldn’t we English-speakers be more familiar with it?

It turns out the situation is a bit muddled in English. From the same article:

Aspect is a somewhat difficult concept to grasp for the speakers of most modern Germanic languages, because they tend to conflate the concept of aspect with the concept of tense. Although English largely separates tense and aspect formally, its aspects (neutral, progressive, perfect and progressive perfect) do not correspond very closely to the distinction of perfective vs. imperfective that is common in most other languages. Furthermore, the separation of tense and aspect in English is not maintained rigidly. One instance of this is the alternation, in some forms of English, between sentences such as “Have you eaten yet?” and “Did you eat yet?”. Another is in the past perfect (“I had eaten”), which sometimes represents the combination of past tense and perfect aspect (“I was full because I had already eaten”), but sometimes simply represents a past action which is anterior to another past action (“A little while after I had eaten, my friend arrived”). (The latter situation is often represented in other languages by a simple perfective tense. Formal Spanish and French use a past anterior tense in cases such as this.)

OK, it’s starting to become clearer why English-speakers aren’t familiar with aspect. But what’s this business about “English largely separates tense and aspect formally”?

According to one prevalent account, the English tense system has only two basic tenses, present and past. No primitive future tense exists in English; the futurity of an event is expressed through the use of the auxiliary verbs “will” and “shall”, by use of a present form, as in “tomorrow we go to Newark”, or by some other means. Present and past, in contrast, can be expressed using direct modifications of the verb, which may be modified further by the progressive aspect (also called the continuous aspect), the perfect aspect, or both. These two aspects are also referred to as BE + ING[6] and HAVE +EN,[7] respectively.

Wikipedia also brings up how Mandarin Chinese fits in with regard to aspect:

Aspect, as discussed here, is a formal property of a language. Some languages distinguish different aspects through overt inflections or words that serve as aspect markers, while others have no overt marking of aspect. […] Mandarin Chinese has the aspect markers -le, -zhe, and -guo to mark the perfective, durative, and experiential aspects,[3] and also marks aspect with adverbs….

If you study modern Chinese grammar, you’ll learn that Mandarin has three aspectual particles (时态助词): 了, 着, and 过. It would be nice if that were all there was to it, but the Chinese situation, similar to the English one, is a bit muddled. That’s about as clear as it gets.

In the case of 了, the word has a split personality and sometimes acts as an aspectual particle, sometimes as a modal particle (语气词), and sometimes both. There is endless fun to be had studying 了 (I know; I took several syntax classes in grad school).

着, on the other hand, is sometimes relieved of its aspectual duties by the adverbs 正 or 在 (or 正在). But then there are some that say that would prefer to draw fine distinctions between these usages as well.

It’s funny to think that Chinese grammar is still in its “Wild West” stage. Linguists are still debating all kinds of fundamental issues of grammar, both within China and without. While you can say with conviction that “Chinese has aspect, not tense,” you can’t say a whole lot more than that. For learners who want to “know the rules,” this can be more than a little frustrating. The good news is that, like all languages, it rewards the persistent. The Kool-aid tastes downright weird at first, but if you just keep drinking it, it starts to taste right.

(If, however, you’re really interested in this whole aspect thing, I recommend you check out Mandarin Chinese: A Functional Reference Grammar, which is about as close as you can get to “classic” in this turbulent field. It has over 50 pages devoted to aspect, with plenty of examples, but be warned: no Chinese characters!)

16

Nov 2009Thinking to Oneself Productively

This is a follow-up to an older post of mine called Talking to Oneself Productively, and the advice this time comes from JP Villanueva. I recommend that you read the full post, but here’s the essence of it (emphasis mine):

> Some functional L2 speakers talk about switching languages like throwing a switch; when they hear a language, they start to ‘think’ in that language, sometimes at the detriment of the other languages. A lot of very highly functional L2 speakers, on the other hand, code switch between L1 and L2 when with peers; both for pragmatic reasons, but also for effect… and for fun; in other words, their switch is pretty loose. In any case, regardless of proficiency, it seems to me that the ability to switch the language of the interior monologue is the mark of a functional L2 speaker. I know plenty of ESL people who say “I mostly think in English now” even if they don’t have superior proficiency.

> So if you’re looking for a language learning tip from me, there it is; try switching your interior monologue to the target language. It will be hard at first, but you’ll make new habits, and it will be come easier, especially if you’re immersed in L2. If you’re not immersed, it won’t hurt either. At the very least, it’s communication practice, even though you’re only communicating with yourself.

> What if you don’t know enough words? Then ask someone for the words, duh. And yes, you should try to ask in the target language. L2 interior monologue might be good practice, but remember that real, target language communication feeds your language instinct, the same instinct that got you from zero to fluent in your L1 in under five years.

Obviously, this is advice that becomes useful at a later stage of development than my “Talking to Oneself Productively” advice. My advice can apply to someone still struggling to form coherent sentences, whereas JP’s “inner monologue” advice will be difficult (or at least frustrating/exhausting) to apply without some degree of fluency already under one’s belt.

Still, this is great advice for someone who can communicate (perhaps haltingly), but finds it difficult to get beyond the need to translate everything mentally. It’s easy to shrug off techniques which are purely mental, but I can tell you from my own experience that these work. They also go a long way toward explaining why some people learn languages much more effectively, even though they seem to be engaged in the exact same activities as other learners.

12

Nov 2009China Ruined the Android Experience

I was pretty excited when I first got my Android phone. Yeah, the Hero a bit sluggish, but that’s been fixed, and the Sense UI is even being updated to support the latest version of Android. So far, so good.

Starting about a month ago, however, I could no longer download anything from the Android Market (Google’s version of the iPhone app store). I figured it was a network glitch that would clear up soon. No, it’s not going to clear up soon. China has blocked all downloads from the Android market.

To be perfectly clear, then, this is what I lose out on, simply because I’m in China:

– No native Facebook integration (Facebook is blocked in China)

– No native Twitter integration (Twitter is blocked in China)

– No new apps of any kind (all downloads from the market are blocked in China)

I bought a phone that does some amazing things. But it depends on the internet working correctly in order to do them. By “working correctly,” of course, I mean not being blocked.

If I want to get around this, I have to pay for a VPN service, and I have to learn how to set it up on my Android phone (potentially complicated). Oh, and the Android phones have just hit the China market. (Not a coincidence.)

On a related note, I was once excited about Google Voice, hoping it could bring me closer to family and friends back home. Now I realize, though, that the idea of Google Voice’s revolutionary services extending to China are simply naive.

I still love living in China, but I have to say, the single most frustrating part of living here for me is watching this government shoot down every single new way the internet is connecting the world.

So yeah, I have a VPN. And yeah, it’s time to get geekier.

09

Nov 2009Hospitals and Train Stations

The past two weeks, I’ve had occasion to visit two different hospitals in Shanghai. Both were large, public hospitals that served a huge volume of patients every day. I came away from both feeling that Chinese train stations and Chinese hospitals are very similar.

– Both serve huge numbers of people

– Both contain a wide cross-section of society

– Both involve a lot of helpless waiting and nerve-wracking purchases

– Both offer VIP options which offer English-language services and a quieter, more private atmosphere

– Both leave you with a sense of wonder and hopelessness at the magnitude of the problems heaped on a government which has to provide for 1.3 billion people.

(I can also totally understand why many of the doctors and nurses had attitudes scarcely better than train station ticket vendors.)

03

Nov 2009No Longer Happy with DreamHost

I haven’t been blogging much lately because I’ve been looking for a new web host in my spare time. I’ve been with DreamHost for years, but recently their service has become unforgivably bad.

My main complaints are:

- My site was hacked while at DreamHost once. (One time is forgivable)

-

My site was later hacked again, which was probably due to outdated web app installations (and not the previous hack). But DreamHost proved amazingly unhelpful in shutting out the hacker. I thought I had shut him out once, but I was wrong. The best solution in this case, then, is to back everything up, make sure it’s all clean, then wipe the original installations and start anew. But if I’m going to do all that, I might as well move to a new host that offers better service and better security.

-

Last weekend my site was down for three days, and DreamHost support never replied to any of my tech requests. I eventually got the attention of a tech support person via live chat, and that person let me know that the security team had actually just moved my site to a different location on the server. Moving it back was trivial. They did it because DreamHost’s WordPress automatic upgrade script creates a backup of the old install (good), but it has a bug which places that directory in a predictable, public location, leaving previous versions’ security exploits online and vulnerable to attack (bad). I was a victim of this bug when I upgraded my WordPress installs, so DreamHost pro-actively (for once) took security measures by moving my entire site’s public directory. They just never told me, and refused to answer my questions. Amazing.

I understand what’s going on here. Basically, I’m the victim of the 80/20 rule. I’m one of those demanding customers who runs multiple sites, and has special needs. It makes a lot more sense for the business to focus on the “easy” customers who have one website that consists entirely of a WordPress install. (Never mind that I’ve brought in lots of referrals over the years, which means more business.)

Anyway, I’ll soon be moving on to a host that still cares more about customer service, and that will be happy to meet my needs. I think I’ve found a good one, but if you have any suggestions, I’d be happy to hear them.

(Incidentally, the first one I tried was Media Temple. The server they randomly assigned me was blocked in China, and when I asked to be switched to a server not blocked in China, the support staff promptly directed me to the refund page. Unbelievable.)

2016 Update: I later switched to WebFaction, and have been very satisfied for years. I recommend it!

27

Oct 2009Michael Love on the Pleco iPhone App

The following is an interview with Pleco founder Michael Love, regarding the Pleco iPhone app, which is now in beta testing.

John: The long wait for the iPhone app has caused much distress amongst all the Pleco fans out there. Any comments on the development process of your first Pleco iPhone app?

Michael: Well, much of the delay stems from the fact that we really only started working on the iPhone version in earnest in January ’09 – before that we were mainly working on finishing / debugging Pleco 2.0 on Windows Mobile and Palm OS. We laid out the feature map for that back in early 2006, when the iPhone was nothing but a glimmer in Steve Jobs’ eye, so by the time Apple released the first iPhone SDK in Spring ’08 we were already well past the point where we could seriously scale back 2.0 in order to get started on the iPhone version sooner.

But as far as how the actual development has gone, the biggest time drain has been working around the things that iPhone OS doesn’t do very well. We’ve gone through the same process on Palm/WM too – we start off implementing everything in the manufacturer-recommended way only to find that there are certain areas of the OS that are too buggy / slow / inflexible and need to be replaced by our own, custom-designed alternatives.

On iPhone the two big problems were file management and text rendering. There’s no built-in mechanism on iPhone for users to load their own data files onto their devices; all they can do is install and uninstall software. So we had to add both our own web browser (for downloading data files from the web) and our own web server (for uploading data file from a computer) in order to allow people to install their own documents / flashcard lists / etc. We also had to implement a very elaborate system for downloading and installing add-on dictionaries and other data

files; for a number of reasons it wasn’t feasible to bundle all of those into the main software package, and again there was no way for users to install those directly from a desktop as they can on other mobile platforms.

And the iPhone’s text rendering system is actually quite slow and inflexible, which is rather disappointing coming from a company with as long and rich a history in the world of computer typography as Apple. The only official mechanism for drawing rich text (multiple fonts, bold, italic, etc) is to render it as a web page, which took way too long and used way too much memory to be practical for us; there also seem to be some bugs in the way Apple’s WebKit page rendering engine handles pages with a mix of Chinese and non-Chinese text. And even simple, non-rich-text input fields and the like are a big performance hog – it took the handwriting recognizer panel about 8x as long to insert a new character into Apple’s text input box as it did to actually recognize a character. So we basically ended up having to write our own versions of three different iPhone user interface controls in order to get the text rendering to work the way we wanted it too.

So a quick-and-dirty port of Pleco on iPhone could probably have been ready last spring, but getting everything working really smoothly took a lot longer.

22

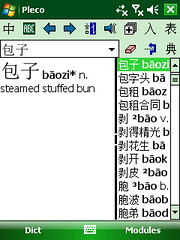

Oct 2009The Pleco iPhone App (beta)

I just recently had the pleasure of trying out the beta version of the new Pleco iPhone app. In case you’re not aware, Pleco is the software company behind what is regarded as the best electronic learner’s Chinese dictionary for any mobile device (and possibly the desktop as well). Given the dearth of really good Chinese dictionaries for the iPhone, Chinese learners have been eagerly awaiting the release of this iPhone app for quite some time. The wait has not been in vain; Pleco for iPhone is an outstanding app.

The Video Demo

Michael Love, Pleco founder, has made a two-part video of the new Pleco iPhone app:

For those of you in China, visit Pleco’s mirror site for the videos.

An All-New UI

I’ve never owned a device running Windows Mobile or Palm OS, so I’ve never been able to own Pleco before, but I’m familiar enough with previous versions to make basic comparisons.

The Pleco user interface received a much-needed makeover for the iPhone. While older versions of Pleco squeezed a plethora of buttons and options onto the screen (you have your stylus, after all), this iPhone Pleco had to find ways to increase buttons to tappable sizes and limit button clutter by hiding options on screens where you don’t need them all. Compare (Windows Mobile on the left, iPhone on the right):