05

Dec 2019Free Chinese Christmas Songs to Spice Up the Holidays

It’s Christmastime again, and time to remind everyone that Sinosplice still has some awesome familiar Christmas songs in Chinese. This year I’m posting a selection of the MP3 files online in streamable format, so be sure you’re viewing the original post on Sinosplice.com if you’d like to play the songs without having to download everything.

All right, here we goooo…

Jingle Bells in Chinese

This is version 1 from the album (Mandarin Chinese):

Jingle Bells in Hakka (Hokkien) Dialect

This song is not part of the album because it is NOT Mandarin Chinese. It’s Hakka. (This one is going to have very limited use for most students; it’s just sort of a novelty for most of us.)

Santa Claus is Coming to Town in Chinese

This one is a kids’ version, version 2, also from the album (Mandarin Chinese):

Santa Claus Is Coming to Town (2)

We Wish You a Merry Christmas in Chinese

This song is especially beginner-friendly for learners of Mandarin Chinese (that chorus!):

Silent Night in Chinese

This one is a Christian classic, of course, version 2 from the album (Mandarin Chinese):

Hark! The Herald Angels Sing in Chinese

Another Christian classic, church choir style (Mandarin Chinese):

Download Christmas Songs (zipfile)

If you want to just grab them all, here you go:

The Sinosplice Chinese Christmas Song Album (~40 MB)

+ Lyrics PDFs (1.2 MB)

Disclaimer: I don’t own the rights to these songs, but no one has minded this form of digital distribution (in the name of education) since 2006, so… Merry Christmas?

MP3 Track Listing

- Jingle Bells

- We Wish You a Merry Christmas

- Santa Claus Is Coming to Town

- Silent Night

- The First Noel

- Hark! The Herald Angels Sing

- What Child Is This

- Joy to the World

- It Came Upon a Midnight Clear

- Jingle Bells

- Santa Claus Is Coming to Town

- Silent Night

- Joy to the World

Merry Christmas everybody… 圣诞快乐!

2023 UPDATE:

While we’re on the subject of Christmas and Chinese, AllSet Learning (my company) is doing a special offer with our 1-on-1 online Chinese classes. 3 lessons (one hour each) is a great quantity to try it out or gift to a loved one!

29

Nov 2019A Revamped Newsletter Approach

I’ve never pushed signing up for a newsletter, but since Sinosplice is only updated once or twice a week, I know it can be hard to keep track of posts on here or remember to check. Not everyone likes the “subscribe to blog via email” option because one email for each blog post can be too much.

I’ve had an AllSet Learning newsletter for a while, but since it’s focused mainly on product announcements, it’s been fairly infrequent in the past.

I’ve decided to do something different, though. I’m combining a sort of bi-weekly “Sinosplice blog post digest” with the AllSet Learning product newsletter and adding some other stuff in as well:

- Recent Sinosplice blog posts

- Recent You Can Learn Chinese podcast episodes

- Recent AllSet Learning blog posts and free study materials

- New AllSet Learning product announcements and promo

For anyone who enjoys this blog, it should be a meaty, useful read, released roughly every two weeks.

The signup in the sidebar of the Sinosplice website is for the same newsletter as the signup on the AllSet Learning website.

Sign up and keep the useful Chinese learning-related content coming to your inbox!

21

Nov 2019Parsing “Xue Xi Qiang Guo” for the Deeper Meaning

A recent topic of conversation among friends in Shanghai is the new app “Xue Xi Qiang Guo.” It’s a news hub for state-sponsored news and commentary, as well as a way to show devotion to the Chinese Communist Party by studying what’s in the app and proving mastery through quizzes. In this way you can get points which can earn you nominal rewards, and it also ties into China’s “social credit” system. (For more info on Xue Xi Qiang Guo, you can check out its official site as well as the Wikipedia’s article.)

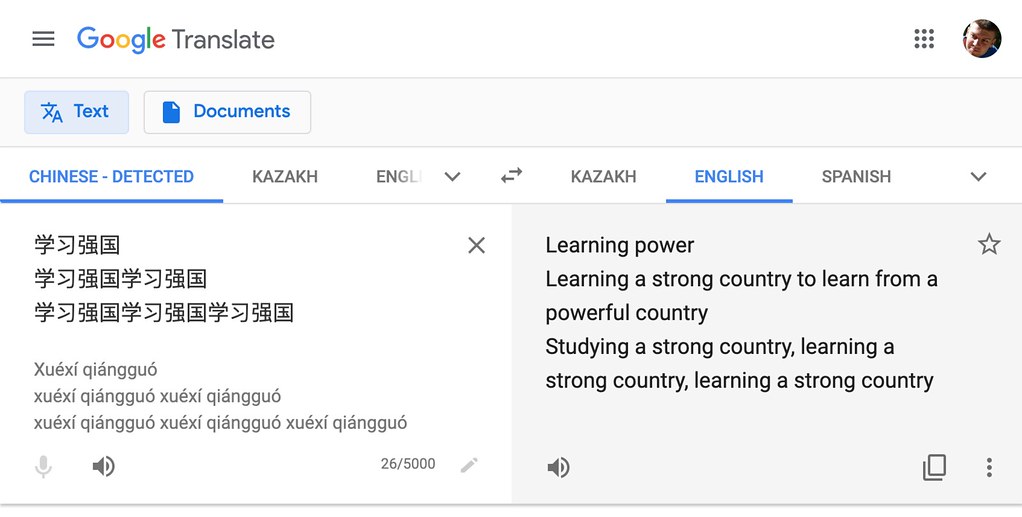

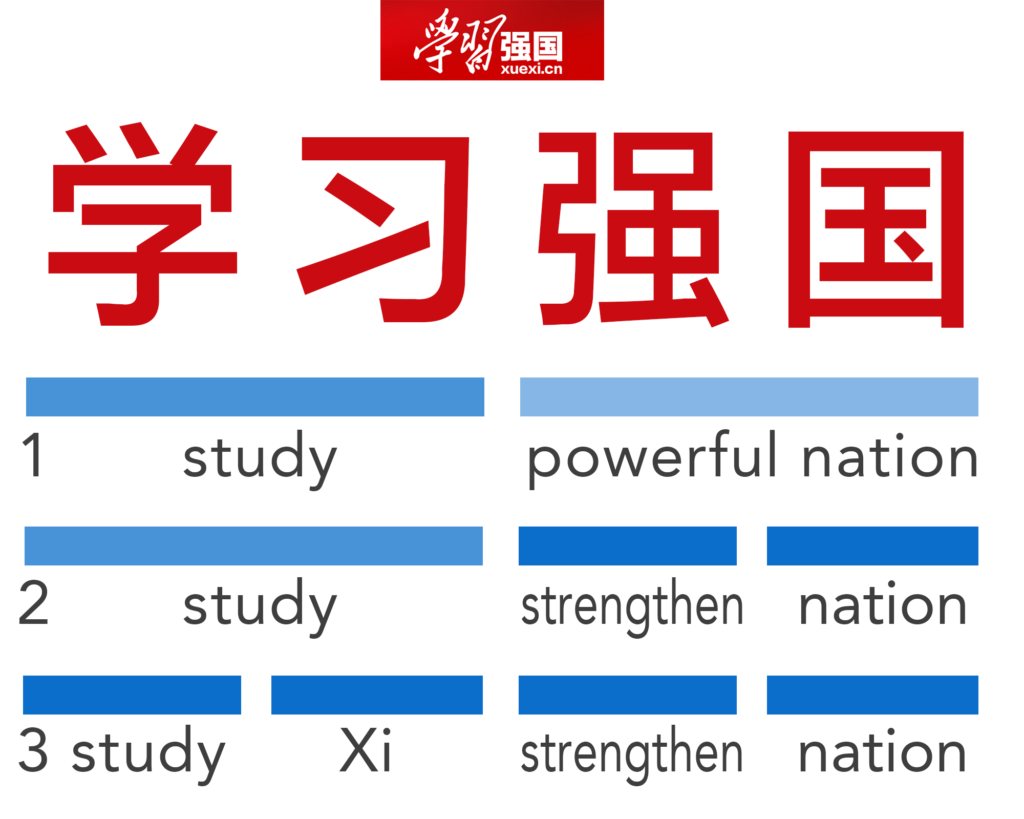

What I want to talk about today is the name: 学习强国. If you plug that into Google Translate, Wenlin, or Pleco, you get a similar two-word breakdown: 学习 强国 (xuéxí qiángguó). You’ll note that English news coverage of the app (including Wikipedia) all write the name in pinyin as two words: “Xuexi Qiangguo.”

But this is Chinese, where clear word boundaries are not provided, and that is not the only breakdown. It’s not even the one that occurs first to most native speakers of Chinese.

1. Xuexi Qiangguo

OK, so 学习 is a given. it means “study,” and it’s certainly in keeping with the spirit of the app. No problem there. The word 强国, meaning “powerful country,” however, is not so common. The overall interpretation here seems to be “learn from the powerful country (China),” which seems plausible, but it’s just not what occurs to Chinese users first. So let’s drop the 强国 parsing (which, unfortunately, seems to be the norm in English language coverage of the app) and see what else we can get.

2. Xuexi Qiang Guo

Classical Chinese was remarkably flexible, most words consisting of individual characters that can serve as various parts of speech in different contexts (noun, verb, and adjective fluidity being common). This trend carries over to modern times for certain words, and 强 is one of them. So while 强 used by itself is most often used to mean “strong” in modern Mandarin, in certain contexts, 强 can also mean “strength” or “strengthen.” So from there, we can get the two-word phrase 强 国 (qiáng guó), “strengthen the country.”

Since the word 学习 (meaning “study”) can also be a noun or a verb, you might translate the full app name literally as something like “Studying Strengthens the Country,” “Study Strengthens the Country,” or even “Study to Strengthen the Country.” This interpretation would likely be the official meaning of the name if you asked the CCP.

3. Xue Xi Qiang Guo

There’s one other unofficial, sly interpretation which goes unnoticed by few Chinese these days. The word 学习 can also be broken down into two separate words. Since the first character, 学, can mean “study” on its own, and the second character, 习, is also the surname of Xi Jinping (president of China), you can also interpret 学 习 as the phrase “xué Xí,” which means “study Xi” or “learn from Xi.” A quick look at the content of the app shows that this interpretation is, indeed, fully grounded in reality. In fact, some are calling the app the “Little Red Book” of the modern age.

In this parsing, the final meanining of 学 习 强 国 would be “Studying Xi Strengthens the Country.” Since cause-effect relationships are often implied in Mandarin, you could also make that a command: “Study Xi to Strengthen the Country.”

Pretty clever name. It is indeed an age of 学 习 (xué Xí). Now there’s an app for that: Xue Xi Qiang Guo.

Nov. 25, 2019 Update: Dr. Victor Mair shared with me his take on this app, which he wrote on Language Log way back in May of this year. I would have linked to it originally if I had been aware of it: The CCP’s Learning / Learning Xi (Thought) app

19

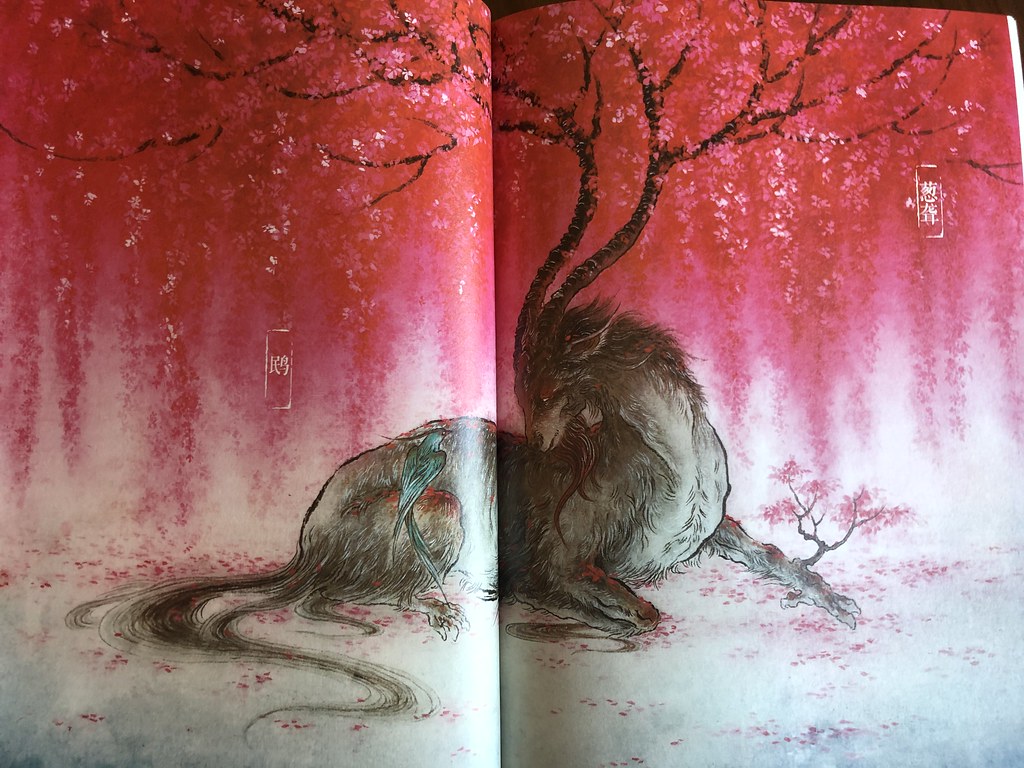

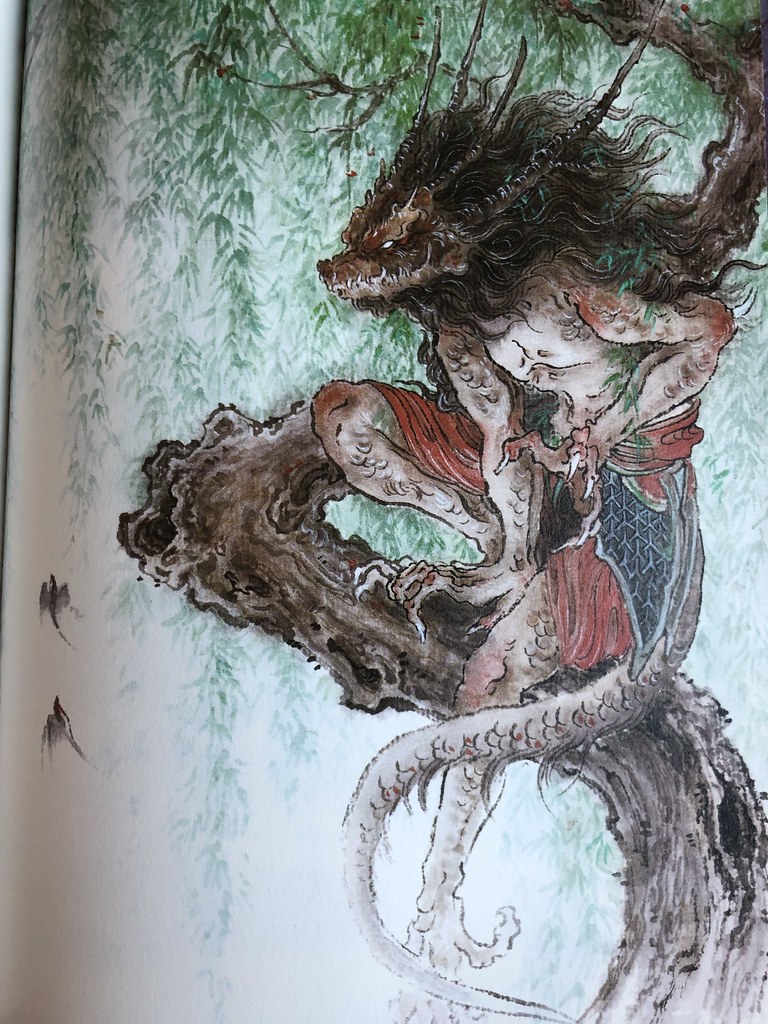

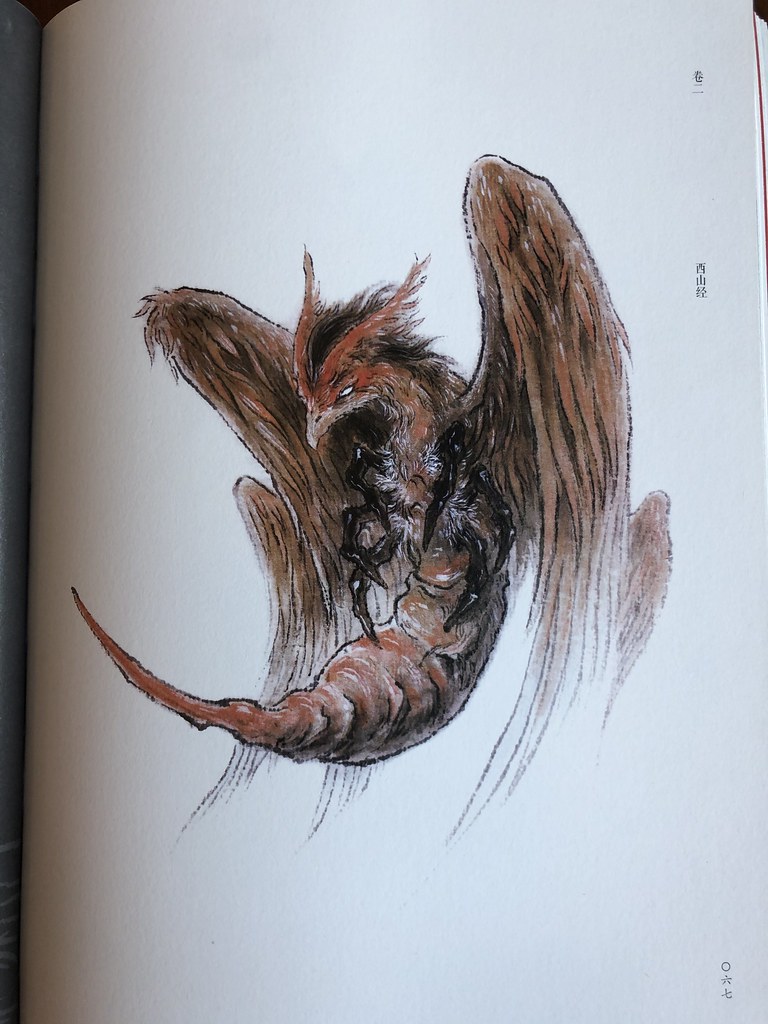

Nov 2019The Fantastical Creatures of Guan Shan Hai

As a kid, I remember getting my hands on a copy of the Dungeons & Dragons Monster Manual. I loved that book! My very Catholic mother would have denounced it as demonic had she discovered it (it was the 80’s, after all), but I just couldn’t get enough of that art.

Over the years, I’ve also thoroughly enjoyed the imaginative creatures featured in Magic: The Gathering or just random stuff on DeviantArt.

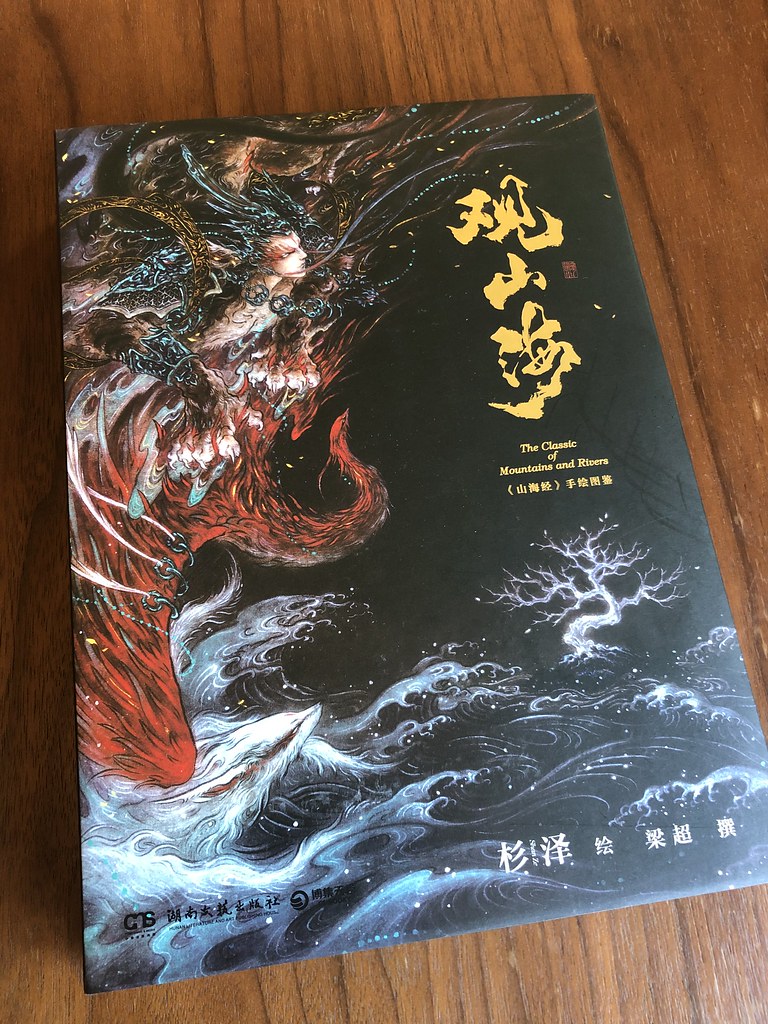

Just recently I came across a book in a book store called 观山海 (Guan Shanhai), just filled with very Chinese illustrations of the beasts from the Chinese classic 山海经 (Shan Hai Jing). I was thoroughly impressed and had to buy it. I’m just sharing a few of the images from the book here.

观山海 (Guan Shanhai) is illustrated by 杉泽 (Shan Ze), edited by 梁超 (Liang Chao), and published by Hunan Literature and Art Publishing House, 2018. (Each page has a passage from the Shan Hai Jing as well as commentary, but I skipped all the commentary for this blog post in favor of the gorgeous artwork.)

13

Nov 2019The Bagel Gets No Respect in China

I love bagels. So I have to say: the bagel has gotten a bum deal in China. It starts with the name.

The Chinese Name for “Bagel” is 贝果

Now, of course 贝果 (bèiguǒ) is a simple transliteration for the English word “bagel.” But there are good transliterations, and there are bad ones.

In this case, the character 贝 means “shell” (like in “shellfish”) and appears in words like 扇贝 (scallop) and 贝壳 (clamshell).

The character 果 means “fruit” or “nut” and appears in words like 水果 (fruit), 苹果 (apple), 坚果 (nut), or 开心果 (pistachio nut).

So with regards to the food-related characters used in the Chinese name for 贝果… that’s 0 for 2 on the food groups! Could this name possibly be confusing?

Knowing that bagels are not well-known among Chinese people, I tested my co-workers. I asked them if they’d ever had a 贝果. They said no. I asked them if they knew what it was. They weren’t sure, but guessed it was some kind of nut.

On the upside (sort of?), I’ve noticed that my pinyin input method (Mac) is giving me the option of a bagel emoji as I type 贝果, and it has cream cheese on it! so maybe not all hope is lost for the bagel in China…

And that’s all I have for you today from the world of hard-hitting bagel journalism in Shanghai.

05

Nov 2019The Crosswalk Posts Have Eyes (update)

Just a few days after my last blog post about New Crosswalk Signals, More Surveillance in Shanghai, one of my friends spotted one of the new crosswalk displays doing its thing:

So what are we seeing here? Photos of a guy crossing the street illegally, with a close-up headshot (taken from the same video surveillance). The Chinese text 涉嫌违法 repeats several times, and means “suspected of breaking the law.” Note also that rather than using facial recognition and searching the guy’s face in the database, then showing his official ID photo, what we’re seeing is just a cropped headshot from the video footage. No official IDing of the “suspect.”

This is not to say that none of that is possible; it almost certainly is (and already happening all the time). It’s just that the “citizen-facing” display screens are still in a restrained testing mode. Until all the bugs are worked out, people aren’t going to be receiving automatic tickets for crossing the street illegally at crosswalks across Shanghai… yet.

But obviously, our faces are getting scanned even more often than before now, and with additional scans there’s additional data to improve the facial recognition accuracy.

30

Oct 2019New Crosswalk Signals, More Surveillance in Shanghai

I’ve noticed these new crosswalk signal “posts” going up all around Shanghai. At first glance, they seem to be a user-friendly upgrade, highly visible with all those lights, and clearer. (All the jaywalking was going on before because people couldn’t see the tiny red guy, right? Sure…)

The thing is, when you look closer, you notice to things:

- There’s a space at the top of each post housing three video cameras: one facing the street, and one facing either side.

- There’s a street-facing screen which currently doesn’t have much on it, but kind of looks like a Windows desktop.

Combine these facts with the AI-powered facial recognition craze that’s sweeping Shanghai, as well as the fact that video cameras in Shanghai can already identify and auto-fine automobiles in real time, and it becomes pretty obvious what’s coming: these crosswalk posts are going to start identifying any jaywalking citizens and fining them automatically. (The little blue and white notice in the bottom photo also says as much.)

As for the under-utilized screen? Possibly it will be used to display photos of offending jaywalkers. (When you get auto-fined on Shanghai’s elevated highways, an LED text screen immediately displays your license plate number, notifying you that you’ve been fined.)

Of course, these crosswalk signal posts won’t do much to stop people from traipsing across streets at other locations, and what happens when people start wearing masks, or wrapping their jackets around their heads specifically to confound the technology at these intersections? Unclear.

It’s a brave new world for Shanghai crosswalks…

Nov. 5, 2018 Update: The Crosswalk Posts Have Eyes

23

Oct 2019One Key Cultural Difference, Demonstrated

You often hear about “the importance of culture” when you learn a language (and I recently did a podcast on that very topic), and a lot of attention is given to “cultural differences” as well. And yet, it’s the kind of thing that doesn’t seem very real until you’re deep into it yourself. It’s kind of hard to demonstrate simply, in an impressive way.

Well, no more! This image will do the trick:

Recently I’ve shown this image to quite a few Chinese friends and co-workers, asking them, “what do you notice right away about this image? What do you think it means?“

With very few exceptions, the Chinese people will talk about the cell phone, and then the gun. The skin color of the person is usually entirely overlooked. Obviously, Americans tend to have a very different answer to those questions.

Then, when you explain how most Americans will view the image, expect a very interesting conversation to follow! Try it.

16

Oct 2019AllSet Learning Has a New Look

I’m pleased to announce that AllSet Learning‘s main website has had a significant makeover. The previous website was built in 2010, and while it worked well enough, these days it was looking more and more like it was built in 2010. No longer!

We’re still doing the VIP hyper-personalized services that we’ve always done (both offline in Shanghai and online), but we also offer some very cool “themed courses” now. They’re real-time online 1-on-1 lessons, focused on a particular topic, but designed to encourage lots of discussion and speaking practice.

Thanks for taking a look at the new site!

11

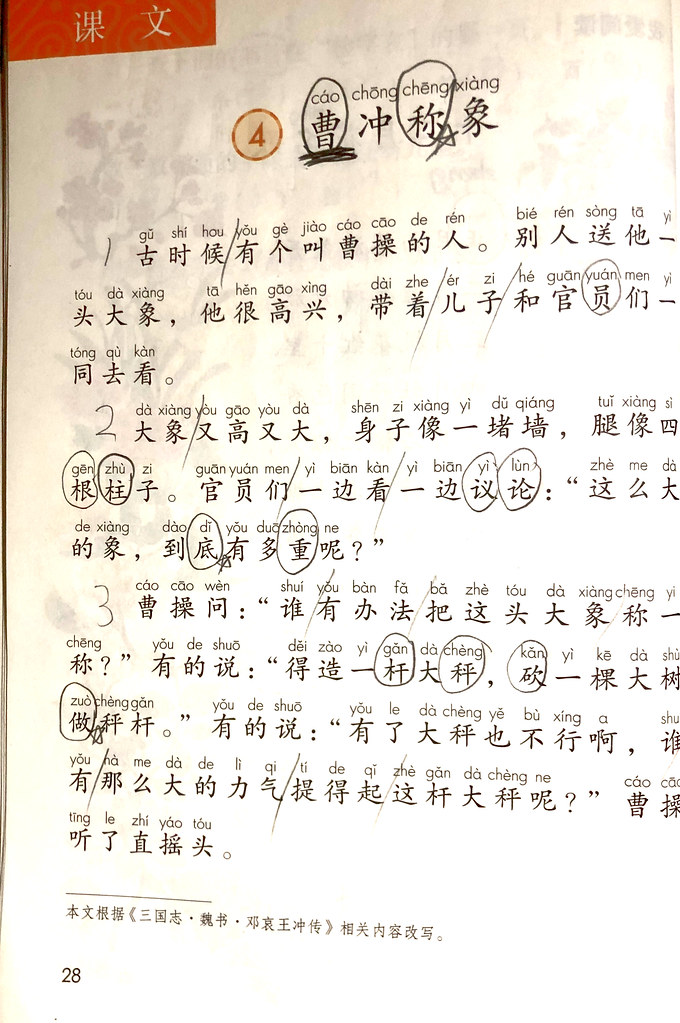

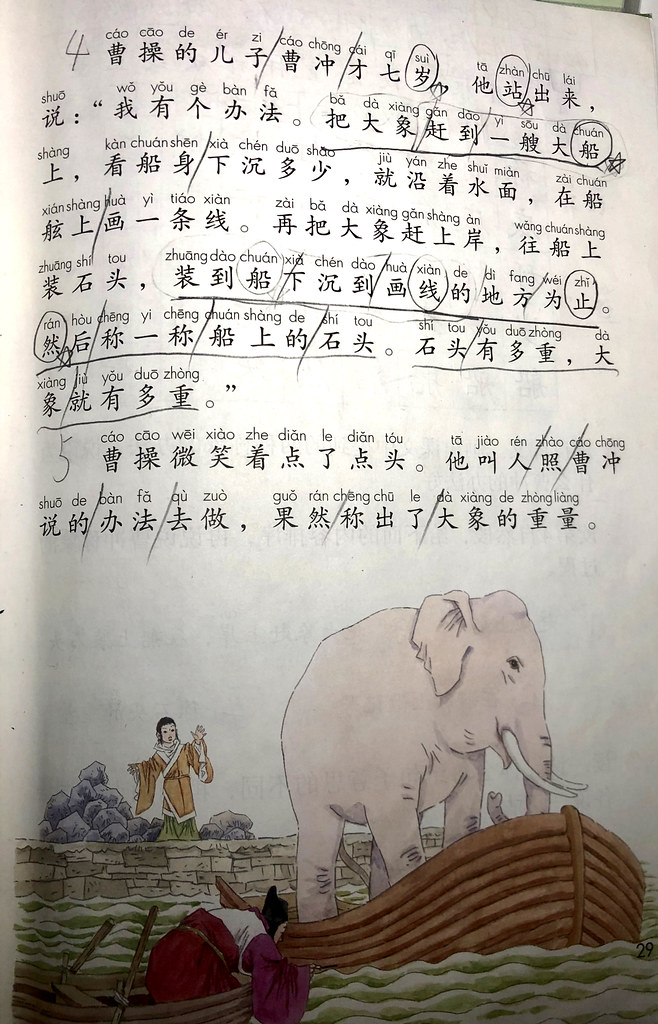

Oct 2019Weighing Elephants and Difficulty

I recently posted a bit about my daughter’s Chinese first grade Chinese language (语文) textbook. I haven’t found the time to dig deeper yet, but I couldn’t help but notice this story from her second grade textbook (and sorry, these photos are not pretty…):

The story of 曹冲 (Cao Chong) devising a way to weigh an elephant is a classic story in China. I wasn’t aware until now that (apparently) second grade is the time for a Chinese child to learn it, if she hasn’t already.

What struck me as interesting about this story is that the very same story is the subject of an Upper Intermediate ChinesePod lesson from 2011: How to Weigh an Elephant (hosted by Jenny Zhu and me). Much of the vocabulary is the same, and the difficulty level is roughly equal.

So… in this particular case, a second grade reading for Chinese kids matches up with an upper intermediate lesson for foreign learners. I’m still exploring the ways that first and second language acquisition differ, in terms of relevant topics, vocabulary, grammar, etc., but this one really jumped out at me.

30

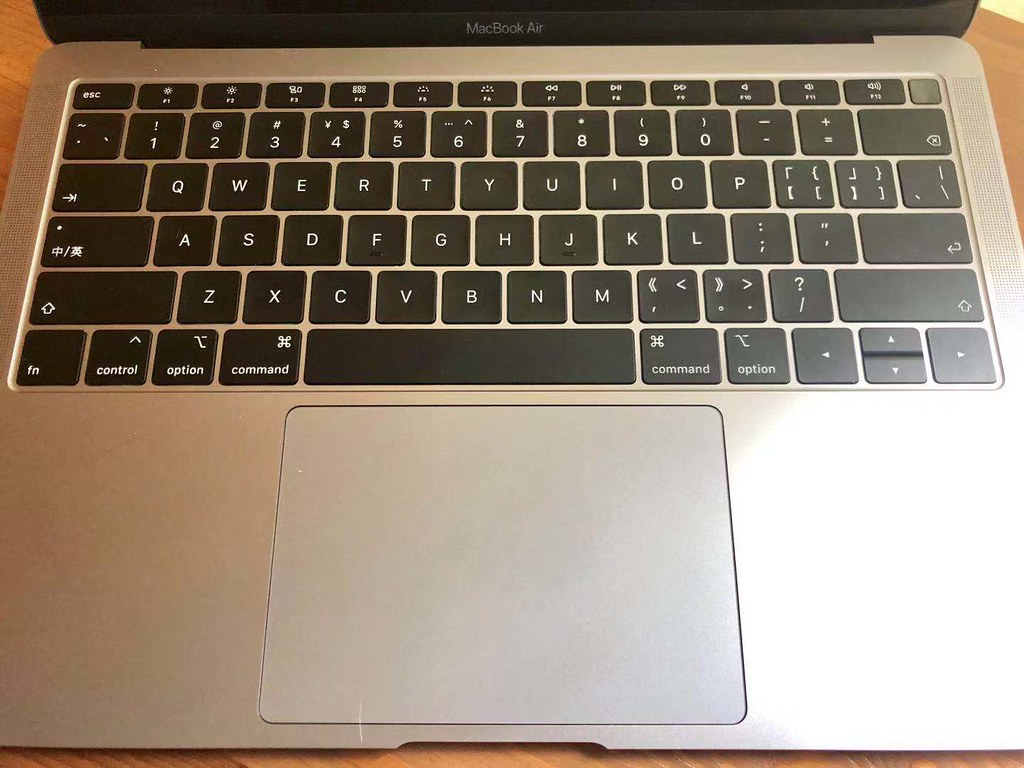

Sep 2019New MacBook, Chinese-r Keyboard This Time

One of the reasons I haven’t been posting lately is that I’ve been struggling with the recovery of a broken MacBook Pro. It was of the (2016) first generation Touchpad line, and, quite frankly, it hasn’t been a great machine. I haven’t lost all faith in Apple hardware yet, but I’ve lost faith in this particular model. I’ve switched back to a MacBook Air. (My old MacBook Air from 2011 still runs like a champ after just a battery replacement a while back, but it’s hard drive is a bit small for today’s standards.)

Anyway, this time it made the most sense to buy the computer in China. You pay significantly more (roughly 1000 RMB) when you buy a MacBook in China as opposed to the US or Japan. What do you get for the extra money?

Well, not much, but you do get a keyboard that looks like this!

It’s actually quite nice to have those Chinese punctuation marks on the keys. (There are a few that I don’t use often and always forget where they are, frequently resulting in a ridiculous trial-and-error key-pecking hunt.) Also, this computer natively repurposes Caps Lock as the “language toggle key” (labeled “中/英”). This is awesome! I didn’t realize how much I was missing.

(Worth 1000 RMB? OK, yeah, that’s a stretch…)

Only problem now is that when I add in a third language (Japanese), the toggle doesn’t work for that one. Anyone out there know the particulars of this specific customization? I need to look into it some more…

18

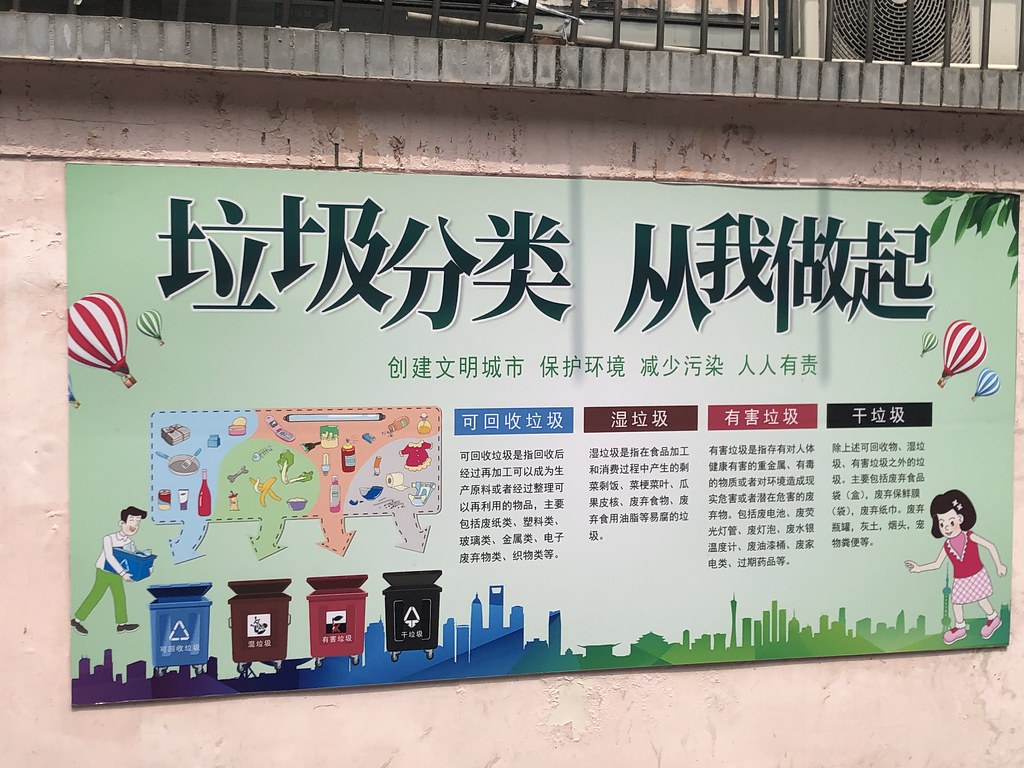

Sep 2019Recycling and Garbage Separation Propaganda

I’m not sure how to classify “normal” Chinese government propaganda. As a foreigner, it all seems kind of pointless, like background noise. Almost a stylistic choice, rather than some kind of effort at shaping (or just nudging) the direction in which society is developing.

Often, the propaganda is of the “values” kind, cheerily informing the population what values Chinese society holds so dear. Other times, they’re more focused on specific objectives. I guess the recent “Sweep Black, Eliminate Evil” campaign from June of this year is of that type, although for the average Shanghai resident, it didn’t really mean anything.

That’s why the recent campaign for recycling and garbage separation feels really different to me. It feels like meaningful propaganda with a tangible (and achievable) objective! I’m not sure what the locals feel about it, but to me, it feels like a rare effort at actual social progress. Here is some of the “propaganda” I spotted in a local neighborhood or two:

(More here.)

10

Sep 2019The Characters a Chinese First Grader Learns

I recently wrote about being amazed by how many characters my daughter learned in a year of Chinese elementary school. I’ve got a lot of thoughts on that, and it’s a great way to highlight the difference between “first language acquisition” and “second language acquisition,” as well as the difference in respective study materials. But first, I just want to share just the lists of characters and words covered in the textbooks of the two semesters of first grade in China. (Otherwise, I’ll never get this stuff done!)

The following word lists come from this 语文 (Chinese language) textbook series, the standard set approved for all Chinese children by the Chinese government in 2018 (and published by 人民教育出版社):

The book on the left is for semester 1 (上册), and the book on the right is for semester 2 (下册).

In the images to follow, the characters in the 写字表 (“Character Writing List”) are all words the kids need to learn to write, even if some of them initially appear in a 识字 (“Character Recognition”) section of the textbook, and some of them first appear in other sections.

Grade 1: Semester 1 (Character List)

Grade 1: Semester 2 (Character List)

Grade 1: Semester 2 (Word List)

This isn’t a comprehensive list of all the words that could be made (or even were covered) by the characters learned in the second semester of first grade. It’s more a list of words that can be formed with the new characters learned and were covered in class. Single-character words are not included in this list. (Note: just perusing this list, you will notice that even in first grade, certain words appear that you would never teach a non-native beginner learner.)

Apologies for the iffy quality… the scanner was acting up. All the characters should be clearly legible, though.

I’ll follow up in a future post with some of my thoughts on all this. I also plan to convert these lists to nice electronic text formats (or maybe just find a place to download them), but if someone else does it first, please share!

In the meantime, beginners, do not despair! You’re not a child, and you won’t learn like one, but you can still learn Chinese. Just differently.

28

Aug 2019Mowing a Lawn in China without a Lawn Mower

There’s a nice green lawn (not too small) inside my apartment complex in Shanghai. I always thought it was weird how I never seemed to see a lawn mower anywhere, but the grass was clearly routinely cut. Then I got my answer:

Yes, the entire lawn is routinely mowed by weed wacker. When you think about it, it does make sense for China, but I know I’ve seen Americans mowing lawns half this size using riding lawn mowers.

22

Aug 2019Kids Ordering Food for the Family

There’s a cultural trend I’ve noticed over the years living in China, and it’s recently come into sharper focus as a result of having my own children and interacting with more Chinese parents. It’s the family habit of letting the child decide the menu for meals, or, in the case of eating out, letting the child decide where to eat or what food to order for everyone. I’m not talking about an occasional thing; I’m talking about a habitual practice.

I probably first noticed this when I started dating my future wife. She lived with her parents, and would frequently communicate with her mom on the phone. I noticed that I would often hear her telling her mom what she wanted for dinner that night, and that’s what her mom would make. I thought this was kind of weird, but figured that was just her family, she was kind of a strong personality, she was good at choosing food everyone likes, etc.

Over the years I learned that this was quite common, and it starts early. Children of 4 or 5 years old frequently decide most of what’s on the menu for the evening, practically every day. In some homes, the child decides their own menu while the adults eat an entirely separate meal. It’s no wonder that so many kids in China are picky eaters!

When this started happening in my own home with my own kids, I quickly put a stop to it. “Kids don’t get to decide what’s for dinner,” I said. “They eat what they’re given.” Fortunately my mother-in-law and wife were cool with that, but they had already started falling into what seems to be the “default mode” of letting the children (usually the youngest) decide what’s for dinner in a Chinese household.

One awkward thing about comparing this aspect of Chinese and American families is that I really only have my own “American cultural experiences” to compare to, and those are not at all recent! I don’t have regular contact with many American families, so if this same habit is now super common in American families too, I wouldn’t know. I suspect that it exists as well, but is nowhere near as widespread as it is in China, where the One Child Policy has set off a cascade of new family dynamics, often resulting in spoiled sibling-less children.

Talking to other parents in Shanghai, what I usually hear is, “my kid often doesn’t want to eat, and is already so skinny. So I’d rather let him decide what to eat and eat something rather than eat nothing.” My reply to this, of course, is, “he’ll be pretty hungry and less picky the next day after he eats nothing for dinner. He won’t starve. 4-year-olds don’t go on hunger strikes.” This works in my family (I’ve let my kids go hungry when they decide they’re going to be picky eaters), but I get the definite impression that Chinese parents think this won’t work in their families (or they’re just not willing to let their kids miss a single meal).

We’re working on a new discussion course for intermediate learners at AllSet Learning focused on various topics related to raising children. It’s really a very, very rich vein for discussion, and it’s the reason this “picky eater” and “kids ordering food” topic resurfaced for me recently. If your experience (American, Chinese, or whatever) is different, please share!

15

Aug 20197up Mojito = Mo7to?

Just a simple China product discovery:

In China, the word “mojito” is not pronounced “mo-hee-to” like it is in English. Rather, the Spanish “j” is approximated with the Chinese “x” sound. In Chinese, it’s written 莫希托 (mòxītuō) or 莫西托 (mòxītuō), or sometimes even 莫希多 (mòxīduō). But it’s not a big step from “xi” to “qi” in Chinese, which makes the xi/qi pun possible, using the number 7 (qī). This gives us: 莫7托 (mòqītuō), as well as the curious English name “Moji7o.”

No comment on the taste! I didn’t buy it or try it.

But we’ve seen “Mint Sprite,” “Green Tea Sprite,” and “Spicy Sprite” before; I guess we shouldn’t be surprised that 7up is getting in on the action.

09

Aug 2019How many ways are there to ask “where are you from” in Chinese? LOTS.

As an English speaker, you may be tempted to think that “where are you from?” is a super basic question. Just 4 words, right? How hard could it be? Well, for this particular question, in the particular language of Mandarin Chinese, it can be phrased more than 10 different ways.

Before I get into this, let’s be clear: I’m not trying to say Chinese is super difficult to learn, or that beginners can’t learn it. No no no no. I may personally feel that the language is kinda hard to learn, but Chinese is not bad at all when it comes to sentence structure in particular. BUT, it’s not unreasonable for beginners to assume that the question “where are you from?” is super straightforward, with just one way to express it in Chinese. And it’s that little assumption that I’m destroying here. You may have to put forward just a bit more effort on this one.

The Swappable Words

A big part of the problem is that in the question “where are you from,” pretty much every part of the sentence can be expressed in multiple ways. Let’s break it down:

- where: 哪里, 哪儿, 什么地方, 哪个国家

So the first two are the most common and should be learned first, but you will hear the others as well, so you have to learn them sooner or later - are… from: 从……来, 来自, 是……的

There aren’t one-to-one translations, they’re roughly corresponding structure. See below for more clarity here. - you: 你

OK, this one you don’t have to worry about much, at least!

The Structures

I live in Shanghai, so I’m going to pick 哪里 and stick with it for these examples. Just keep in mind that most of the others probably work as well.

- 你从哪里来? (Nǐ cóng nǎlǐ lái?)

- 你来自哪里? (Nǐ láizì nǎlǐ?)

- 你是哪里人? (Nǐ shì nǎlǐ rén?)

- 你是哪里的? (Nǐ shì nǎlǐ de?)

- 你是(从)哪里来的? (Nǐ shì (cóng) nǎlǐ lái de?)

The Big “Where are you from?” List

OK, now let’s put all these words and structures together and see how many sentences we can come up with!

- 你从哪里来? (Nǐ cóng nǎli lái?)

- 你从哪儿来? (Nǐ cóng nǎr lái?)

- 你从什么地方来? (Nǐ cóng shénme dìfang lái?)

- 你从哪个国家来? (Nǐ cóng nǎge guójiā lái?)

- 你来自哪里? (Nǐ láizì nǎli?)

- 你来自哪儿? (Nǐ láizì nǎr?)

- 你来自么地方来? (Nǐ láizì má dìfang lái?)

- 你来自哪个国家? (Nǐ láizì nǎge guójiā?)

- 你是哪里人? (Nǐ shì nǎli rén?)

- 你是哪儿人? (Nǐ shì nǎr rén?)

- 你是什么地方的人? (Nǐ shì shénme dìfang de rén?)

- 你是哪个国家的人? (Nǐ shì nǎge guójiā de rén?)

- 你是哪里的? (Nǐ shì nǎli de?)

- 你是哪儿的? (Nǐ shì nǎr de?)

- 你是什么地方的? (Nǐ shì shénme dìfang de?)

- 你是哪个国家的? (Nǐ shì nǎge guójiā de?)

- 你是(从)哪里来的? (Nǐ shì (cóng) nǎli lái de?)

- 你是(从)哪儿来的? (Nǐ shì (cóng) nǎr lái de?)

- 你是(从)什么地方来的? (Nǐ shì (cóng) shénme dìfang lái de?)

- 你是(从)哪个国家来的? (Nǐ shì (cóng) nǎge guójiā lái de?)

Wow, that’s kind of a lot. The good news is that there a few that are used much more often than the others. Different native speakers will have different opinions on which ones are the most common, and it’s also partially dependent on region.

The “Where are you from?” Shortlist

You’ll hear lots of these in China, but after I asked a bunch of Chinese teachers, the most common favorites were:

- 你是哪里人? (Nǐ shì nǎlǐ rén?) — popular with southerners

- 你是哪儿人?(Nǐ shì nǎr rén?) — popular with northerners

- 你是哪个国家的? (Nǐ shì nǎge guójiā de?)

What might be surprising is that the question which most learners start with is not in the list:

- 你从哪里来? (Nǐ cóng nǎlǐ lái?)

- 你从哪儿来? (Nǐ cóng nǎr lái?)

When asked, the teachers say that’s because it sounds a bit formal (same with using 来自). That doesn’t mean that a beginner shouldn’t use it, though… it’s still fine.

Learner Shortcuts

So I bet you want to just pick one, memorize it, and use it exclusively, right? That’s fine. You can do that.

BUT, that’s not necessarily going to help you when you talk to random strangers in China. They are going to ask you where you’re from, and that’s when the big “Wheel of ‘where are you from?’” is spun, and the gods determine your fate.

Rather than memorizing 20 “where are you from” question forms, go with your gut. If you just started chatting, and you hear a 哪里 or a 哪儿 (exception: taxi drivers!), and maybe a 国家 or a 地方 or a 的 on the end, just assume they’re asking where you’re from. This usually works.

Pro tip: Also be sure to answer in a complete sentence. Something like: “我是美国人。“. This way if you guessed wrong about what the person was asking, that person won’t be too confused by your answer.

Conclusions

I’m not saying you have to learn 20 ways to ask “where are you from?”

I am saying that if you are feeling frustrated because you’ve been studying for a while, but you still sometimes can’t understand the simple question “where are you from?” that there is actually a good reason, and it’s the fault of the Chinese language, not your fault.

Over time, you will get these. It’s just a little more work than memorizing one sentence.

06

Aug 2019Learning Chinese Memes from Mandarin Companion

I appreciate a good meme, and recently my partner Jared at Mandarin Companion has been on a meme roll. He started by collecting some good ones, then he moved on to posting his own on the Mandarin Companion Instagram account.

Here are a few I especially like:

There are more on the Mandarin Companion Instagram account.

Also, we’ve got a new book out at the “Breakthrough Level” (150 characters):

It’s always fun writing sci-fi. The original concept was by Jared, and we fleshed the plot out together. I oversaw our Chinese writers, and I did all the illustration design. Fun stuff!

18

Jul 2019Grammar Points for the HSK

The Chinese Grammar Wiki has been around for a while now, and we’ve released an A1-A2 Elementary book, and well as a B1 Intermediate book. But for HSK test takers, it’s always been slightly confusing trying to match up the CEFR levels (A1, A2, B1, B2) with the HSK levels.

Well, we’ve now done the extra work to make separate (parallel) lists of grammar points specifically for the HSK. It was a lot more work than I originally expected, but I think it’s going to be helpful to a lot of people.

Here’s how we explain the relationship between the levels in the book itself:

The current version of the HSK (Hanyu Shuiping Kaoshi) dates back to 2010, and was last revised in 2012. It consists of six levels (1-6), and was designed, in part, to correspond to the six CEFR levels. European Chinese language teachers have reported that the correspondence, in practice, is somewhat different, with HSK 6 actually matching no higher than the CEFR B2-C1 level range. Furthermore, the HSK levels are used more as a standard for academic requirements (e.g. being admitted to an undergraduate or graduate program in China) rather than real-life application….

Our conclusion is that while both leveling systems clearly have their uses, it is not possible to equally accommodate both systems in one list of grammar points. That is why the Chinese Grammar Wiki has created separate listings for CEFR levels and HSK levels. We encourage test-takers of the HSK to refer to the HSK level lists, while learners focused more on real-life communication can benefit more from the CEFR levels. This book focuses on the HSK levels.

The HSK 1 and HSK 2 books are already on Amazon, with iTunes versions and HSK 3 soon to follow.

Plus, there are also new grammar points lists on the Chinese Grammar Wiki itself:

17

Jul 2019American Insanity

I’m in Florida on vacation with the family this July. I’ve managed to get my kids to a respectable bilingual state despite them growing up in Shanghai, but American culture is one thing my kids just don’t get a lot of, and it’s probably one of the most interesting aspects of this trip. Kids adapt to new surroundings quickly, but their reactions to new situations and unfamiliar American culture is super interesting.

Unfortunately, it’s not practical to make a big long list (I wish I had one!). One simple example is wading pools, though. My parents never got a pool installed, but the backyard is plenty big, so we can do the old backyard wading pool thing (fill it up with a hose). Such simple pleasures are utterly foreign to Shanghai kids, but still a blast! (Coming up soon: backyard water balloon fight, “Slip ‘n Slide,” and playing in the sprinkler. Classic American middle class fun!)

Anyway, the insanity part relates to a conversation with my daughter (now 7.7 years old). It went something like this:

Her: Is America insane?

Me: …. Yes.

Her: BWAHAHAHA!

Me: ….

Her: Why?

Me: ….

Her: BWAHAHAHA!

I guess maniacal laughter is better than weeping. I mean, “chaos is a ladder,” right?