02

Nov 2012Sapore di Cina for Chinese Learners

I’d like to call attention to a relatively new blog on learning Chinese by Furio from Italy. It’s called Sapore di Cina (“Flavor of China” in Italian), and the author has a lot of good ideas (in English). A lot of his recommendations are the types of things I tell learners as well, so if you like Sinosplice’s entries on learning Chinese, there’s a good chance you’ll like Furio’s blog.

The blog post that first got my attention was Learn Chinese online: 27 excellent free resources. It’s a good list, and since any list of this sort doesn’t stay up to date for long, it’s good to check it out now. I was happy to see the Chinese Grammar Wiki in Furio’s list of resources.

Recently Furio published ChinesePod Review – An alternative way to learn Chinese. I won’t deny that it’s a complimentary review of ChinesePod in general (and me in particular), but one of the good things about this review is the Furio calls attention to some of the more effective (and economical) ways to get the most out of ChinesePod.

I’ve added Sapore di Cina to my on short list of Chinese resources on Sinosplice. Check it out!

30

Oct 2012Halloween Vocab Challenges

I’ve always found it a bit tricky at first to talk about holidays in Chinese. The Chinese holidays involve these things that we just don’t have, so it’s not a matter of translation, it’s a matter learning what these things are and what they’re called. 红包, 粽子, 对联, 扫墓, etc. Fortunately, that’s a pretty interesting learning process most of the time (especially if you’re learning the stuff hands-on in China), so all is well and good there.

And then there’s explaining the western holidays to the Chinese. Sure, the Chinese already know a lot about western holidays, so frequently all you have to do is fill in a few of the gaps. The fun part of figuring out where the gaps are, and what misperceptions there are. I’ve always enjoyed this too.

Halloween (万圣节) seems to bring a few of its own challenges, however. The concept is easy for the Chinese to get: it’s a 鬼节 (a “ghost festival”). It’s the trivial things that tend to pose challenges here. How would you say the following in Chinese?

– What are you going to be for Halloween?

– Don’t forget to wear a costume.

– Why didn’t you dress up?

The concept of “Halloween costume” does not seem to have standard translations, and you can get different answers from different people. I’ve been down this road before, and it can get a little confusing. The key is to focus on the verb for “dress up” rather than on the noun “costume.” Here is some of the language I hear Halloween-happy Chinese young people using:

– 你要穿什么? This one is a little vague, because it just asks “what are you going to wear,” which might apply to any party.

– 你要扮什么? This one gets more into the costume/disguise theme, sort of like asking, “what are you going to dress up as?”

– 别忘了装扮自己。 Here we see the verb 装扮, which is probably the most appropriate verb for dressing up for some role, although it seems a little overly specific for everyday usage. But it literally means, “don’t forget to disguise yourself.”

The 扮 in 装扮 (“to disguise oneself”) is not the same one as in the phrase 怎么办; it’s the 扮 from 打扮, which is most often used to mean “make oneself up” or “deck oneself out” (for a night on the town). Or you fans of role-play might also know it as the 扮 from 扮演, meaning “to play a role.” (Indeed, the formal Chinese translation for “role-playing game” is even 角色扮演游戏.)

One thing is for sure: Halloween parties are a great occasion to learn obscure vocabulary! I leave you with a last question (in 2 flavors), which very well might come in handy if the Halloween parties you attend are anything like the ones I’ve attended in China:

– 你扮的是什么? “What are you dressed up as?”

– 你这是什么装扮? “What are you supposed to be?”

23

Oct 2012Chinese Grammar Survey – Respondents Needed!

One of my teachers at AllSet Learning is doing his masters thesis on online resources for learning Chinese, and naturally, he was intrigued by what we’ve built so far at the Chinese Grammar Wiki. So he decided to research the topic and help us out at the same time by doing a learner questionnaire.

Sinosplice readers, we could really use your help! It should only take a few minutes. The questions are easy.

– If you’ve never used the Chinese Grammar Wiki, we’d still love you to complete the survey.

– If you have used the Chinese Grammar Wiki, we’d especially love you to complete the survey.

Thanks so much, everyone, for your time. We’re building a massive online resource, and this kind of feedback is very valuable.

Oct. 29 UPDATE: We’ve gotten all the responses we needed. Thanks very much to everyone who answered the survey.

18

Oct 2012Creative Character Signage

Long-time readers of this blog know that I’m a fan of creativity centered on characters. I recently discovered these signs browsing photos on WeChat. (I’ll post the Chinese characters below the photos if you want to give yourself the challenge of reading them on your own.)

The characters on the sign above are: 时光机 (“time machine”).

The characters on the two signs above are: 锅炉房 (“boiler room”).

15

Oct 2012Pascal’s Triangle and Chinese

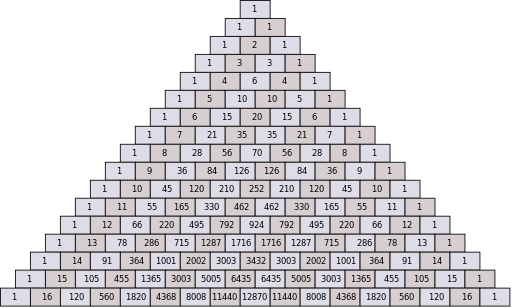

This is one of those blog posts where I take two seemingly very different topics and connect them to China or Chinese. This time it’s about Pascal’s Triangle, one of my favorite mathematical concepts. In case you’re unfamiliar with Pascal’s Triangle, here are some images from Wikimedia Commons that nicely illustrate the principle:

Here’s the China connection (via Wikipedia):

> The set of numbers that form Pascal’s triangle were known before Pascal. However, Pascal developed many uses of it and was the first one to organize all the information together in his treatise, Traité du triangle arithmétique (1653). The numbers originally arose from Hindu studies of combinatorics and binomial numbers and the Greeks’ study of figurate numbers.

> […]

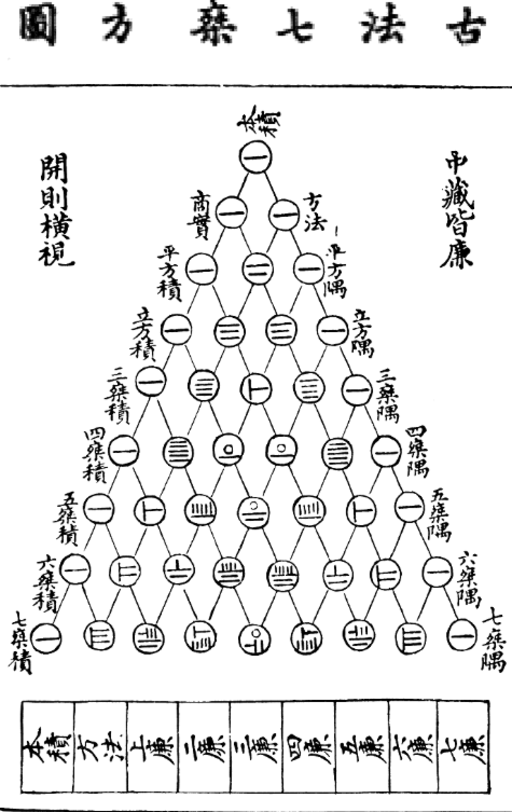

> In 13th century, Yang Hui [杨辉] (1238–1298) presented the arithmetic triangle that is the same as Pascal’s triangle. Pascal’s triangle is called Yang Hui’s triangle in China. The “Yang Hui’s triangle” was known in China in the early 11th century by the Chinese mathematician Jia Xian [贾宪] (1010–1070).

Yang Hui’s diagram contains some interesting-looking numbers. Check it out:

Compare that to Pascal’s triangle above. What’s up with these Chinese numbers? You can follow the upper-right to lower-left diagonal (one row in) to follow the numbers 1-8. You get this:

1. 一

2. 二

3. 三

4. 亖

5. [no Unicode symbol for this one; it’s just 亖 + 一 (vertical)]

6. ᅡ

7. ᅣ

8. [no Unicode symbol for this one; it’s just ᅵ + 三 (horizontal)]

You can gather that 10 is 으 [a symbol I borrowed from Korean Hangul for the purposes of this post], which also looks like “10” turned sideways. 20, though, is 〇二 [except with the 〇 sitting on top of the 二], and so on.

I’ve written before on Chinese number character variants, but these are different from those. The numbers look similar to Suzhou numerals and Shang oracle numerals, but are still a bit different from both. I’m curious if anyone out there know more about these numbers? The diagram supposedly dates to 1303 (more info on Wikimedia Commons).

There’s another personal connection between me and Pascal’s Triangle. As part of my research for AllSet Learning, I make use of basic set theory and higher-level Venn diagrams. Considering that in a Venn diagram, by definition, all possible logical relations between sets must be represented, it can get quite tricky to draw these things when you delve into Venn diagrams with higher numbers of sets (more than 3). But how do you know how many overlapping regions there are in the Venn diagrams as the numbers of sets increase? Pascal’s triangle.

(BTW, some of the research we’re doing now at AllSet Learning could make use of interns with a foundation in statistics, mathematics, or computer science. If that’s you, get in touch! More on AllSet Learning’s interns here.)

12

Oct 2012Help with Absentee Ballot Mailing

The U.S. Consulate in Shanghai is helping U.S. citizens mail their ballots back to meet the state deadlines:

> Returning your ballot by mail. Place your voted ballot in a U.S. postage-paid envelope containing the address of your local election officials. Drop it off at the Consulate and we’ll send it back home for you without the need to pay international postage. If you can’t visit the Consulate in person, ask a friend or colleague drop it off for you. If it’s easier for you to use China’s postal system, be sure to affix sufficient international postage, and allow sufficient time for international mail delivery. If time is tight, you may want to use a private courier service (e.g., FedEx, UPS, or DHL) to meet your state’s ballot receipt deadline.

> You can submit your ballot to us to be delivered by diplomatic pouch at the entrance to the consular section at the 8th Floor, Westgate Mall, 1038 Nanjing West Road, between the hours of 8:30am and 5pm on weekdays. Your ballot must be sealed in the security envelope and mailing envelope. However, since it takes up to three weeks to send mail to the U.S. via our diplomatic pouch, we recommend you drop off your ballot of no later than next Tuesday, October 16. After that time, we recommend you use an express private courier service such as the ones mentioned above to ensure your ballot arrives on time.

Nice!

Email source: “Message for U.S. Citizens: Completing and Returning Absentee Ballots” from ShanghaiACS@state.gov

09

Oct 2012Unfun Map Games

I recently updated the Explore Shanghai app on my iPhone and was saddened to see this:

Take note of this part:

> If you find that street maps are shifted after upgrading to iOS6, check the settings in the Help tab. Choose “Enable shift” if you use AutoNavi-powered maps for China-purchased devices, choose “Disable shift” if you use TomTom-powered maps for international-purchased devices.

Huh? What’s going on here?

I’m no expert on this issue, but essentially, the Chinese government is paranoid about the use of GPS, and screws with it. This affects Google Maps, it affects camera GPS, and it even affects runners’ watches. It’s been going on for years. Chinese companies with government approval (like TomTom) can get their services/devices working properly, but foreign devices which try to rely on good old-fashioned “satellite positioning” and maps lose out, and have to build in a “shift correction” feature if they want their apps’ GPS positioning to work properly.

This has been an annoying issue in China for years. I’m wondering if there is some kind of central resource for help on this issue, similar to this site for blocked websites in China. Anyone?

It’s really sad to see the government continuing this charade in all its forms. It doesn’t work. When developers don’t solve the issue directly, there are workarounds to the map issue for pretty much any device, if you really dig. It’s just a huge pain in the GPS.

04

Oct 2012Diaoyu Islands with Cake and Murakami

This is an “apolitical” blog, so I won’t say much. But I was highly amused to see this cake for sale in Chengdu while I was there over the holiday:

One of my favorite authors is the Japanese master of magical realism, Haruki Murakami (村上春树 in Chinese), and I liked what he had to say on the issue:

> “When a territorial issue ceases to be a practical matter and enters the realm of ‘national emotions’, it creates a dangerous situation with no exit.

> “It is like cheap liquor. Cheap liquor gets you drunk after only a few shots and makes you hysterical.

> “It makes you speak loudly and act rudely… But after your drunken rampage you are left with nothing but an awful headache the next morning.

> “We must be careful about politicians and polemicists who lavish us with this cheap liquor and fan this kind of rampage,” he wrote.

Quote via China Digital Times.

28

Sep 2012Morphing Mooncake Madness

As Mid-Autumn Moon Festival (中秋节) approaches (this year it’s September 30th), there is a lot of mooncake buying going on in Shanghai. It’s still a tradition to buy mooncakes (月饼), and although some people like them, a lot of the mooncake purchases are for clients, employees, etc. But exactly what the mooncakes are is changing quite a bit, and some of the new forms (like Haagen Dazs’s) have a bit more hope of appealing to younger palates. The traditional recipes are getting cast by the wayside more and more, it seems, as modern corporations muscle in on the holiday market.

Over the past month, I’ve taken various snapshots of the current state of mooncake commercialism.

Just to be clear, we can see the type of traditional mooncake that young Chinese people don’t like much anymore in this Christine ad:

The demand is still fairly strong, and there have been mooncake lines going around Shanghai’s Jing’an Temple for at least a month. But you’ll notice that most of the people buying them are middle-aged or older.

Here’s a Hong Kong mooncake trying to do a more modern take:

Haagen Dazs seems to be championing the idea, “if people are going to keep buying mooncakes, let’s give them tasty, pricey alternatives.” And it’s the most visible “traditional mooncake alternative” this year:

I’m really expecting traditional mooncakes to become something of a rarity over the next 20 years.

25

Sep 2012iOS6 has your iPhone speaking Chinese

I got a great tip from my friend Will Stevenson yesterday. Apparently iOS6 not only added text-to-speech support for new languages, but also enabled the ability to recognize and read out Chinese, even when the phone is in English language mode, and even when the text is a mix of Chinese and English.

What it is

Here’s an example of “Speak” enabled for a Chinese spam text:

Here’s an example of “Speak” for a note which includes both English and Chinese (I’m not sure why there’s a choice of reading in either 中文 or English; either one does the same thing):

For text messages, iOS treats each SMS text as one big block of text, and it won’t highlight individual words as it reads them (even though it reads them all). For other types of text, though, in apps like the Notes app, it will highlight each character as it reads it out:

How to enable it

Anyway, since you’re likely here to get your iOS6 device speaking Chinese, here’s how you do it.

First, go to Settings > General > Accessibility (Accessibility is near the bottom of all the stuff in “General.” Just a little hard to find. Naturally.)

Right at the top, you’ll see an Accessibility section called “Vision.” There you’ll see an item called “Speak Selection.” Touch on that. On the next screen, turn it ON. You can also turn no “Highlight Words” here too (why not?). You probably don’t want to mess with the speaking rate. It gets way too fast pretty quickly.

Here’s the really cool thing, though. There’s a “Dialects” section. (And no, I’m not going into the “what is a dialect, really? discussion here!) In there, you can not only choose the dialect for English and other languages, but also for Chinese! At the bottom of the “Dialects” section, under 中文, you can choose mainland Mandarin (中国), Cantonese (廣東話), and Taiwanese Mandarin (台灣). Not sure why they chose two regions and a language/dialect/topolect as the choices. But anyway, fun stuff!

What it means

Why does this matter? Well, my friend Will discovered it by accident as he was going through the somewhat tedious routine of copying a text so that he could then paste it into Pleco‘s pasteboard reader. He tried playing the text, and much to his surprise, he could hear the Chinese (whereas in the past, on iOS5, the text-to-speech converter would just skip over all Chinese). In this particular example, after having the Chinese read to him, he didn’t need to look it up after all.

Because a lot of the challenge of Chinese is simply recognizing the characters for the words you already know, text-to-speech can be extremely convenient. Will’s reaction was, “now that I have this feature, I’m going to be using Pleco a lot less now!”

Interesting. Let me know if you think this new feature changes how you learn Chinese on your phone, or if it’s just no big deal to you.

20

Sep 2012The Road Too-Traveled

It’s almost National Day holiday in China. That means wacky vacation schedules (it’s not too bad this year, though) and tons of Chinese people traveling. Those of us that have tried traveling within China during the holiday tend not to repeat it too many times (or at least not to really popular tourist destinations).

This year my wife and I are going to make a trip out to Chengdu. Should be fun (as long as the crowds aren’t too overwhelming). We’re going to try time-shifting our holiday a bit (leaving early and coming back in the middle of the holiday) to offset the holiday rush. We’ll see if that works!

Recently I saw this advertisement, which I assume was timed to appeal to would-be National Day travelers:

The text reads:

> 没有起点 没有终点 路线你定!租!

> There is no starting line. There is no finish line. You set the route! Rent!

Of course, the first thing that went through my mind when I saw that ad was, “you’re never going to find a road like that in China.” It’s not that the “open road” doesn’t exist at all; they’re just way too remote for the average driver setting out for Shanghai, that’s for sure. A Chinese “road trip” tends to feel more like driving in the city than like the “open road.” I’ve been on a few road trips in China, and I can now appreciate why the road trip is a great American tradition and not a Chinese tradition.

12

Sep 2012A Visual Case for Stroke Order

Inevitably, students of Chinese characters will ask, at some point, “why do we have to learn stroke order? What difference does it make?”

It’s a good question. This is the answer:

(The message reads 好无聊. “So bored.”)

This is what Chinese characters start to look like as the strokes flow together. And it’s not just about calligraphy and an appreciation of ancient culture; I discovered the image above through Tencent’s WeChat (the iPhone app).

10

Sep 2012AllSet Learning Pinyin App in Video

I’ve been quite busy with AllSet Learning lately and haven’t been updating Sinosplice (oh, the blogger guilt!), but here’s a little video we did lately to provide an easy preview for the AllSet Learning Pinyin ipad app:

The app is doing great! Thanks very much to everyone who’s downloaded it, recommended it to friends, and purchased the optional addons.

If you don’t have the app, you can get AllSet Learning Pinyin here.

31

Aug 2012Graham’s SRS Method

Sinosplice commenter Graham Bond recently left a lengthy and interesting comment on my Misgivings about SRS post. (“SRS” refers to spaced repetition system like Anki; I explain how SRS works in an earlier post.)

I quote Graham’s comment here, almost in its entirety, adding in a few links and just a little emphasis:

I have become a hopelessly-addicted SRS user in recent months. This decision came at something of an impasse in my (nine year-long) Chinese language-learning journey, and was made largely on the back of blog I came across, the author of which was positively evangelical about the possibilities of the technology.

By now – nine months in – I recognise all of the problems and limitations cited above. I was mistaken to think, as many others have, that SRS was a cure to all language-acquisition ills. It is bound to unnaturally skew one’s priorities and lead to the kind of imbalanced result you allude to in your post (ie. I have bulging vocabularly pecs, and puny grammatical legs). That said, it has proved useful in certain respects, not least in introducing a competitive element to language-learning (albeit one in which I compete with myself) and imposing quite a hard-edged discipline (ie. I gotta get through my character sets every day, regardless of how I feel, otherwise the ‘overdue cards’ count mounts very quickly….this can verge on the pathological).

My current set up attempts to address some of the deficiencies mentioned above. Though it’s probably very, very boring, I’ll set out my current arrangements, as briefly as possible, in the hope of explaining how they work for me (and occasionally, how they do not).

I have four decks of cards which, in total, I spend around an hour trawling through daily.

Only one of these, the HSK deck, was downloaded and, as such, contains many words and (at Level 6) idioms which are completely devoid of context for me. Because of the sheer size of the contemporary Level 6 HSK category (1,400+ words), I have had to introduce new cards slowly – I try for 10-20 new words per day – in the hope that by the end of this year, 2012, I will be juggling all cards (about 2,500 for Levels 1-6), while never having to face a single daily session of more than, say, 150 words at one time.

I download daily audio from YouTube clips of 美国之音 TV news broadcasts and listen to them as MP3 files whilst commuting, or taking a stroll. I attempt to listen to at least 20-minutes worth of broadcast material daily. Additionally, I force myself to read at least one Chinese news article (I occasionally substitute this with a page or two of a novel) per day, regardless of subject. These two activities have allowed me to locate the usage of a lot of the fairly formal words or obscures idioms that I have come across in my HSK drills (especially when I read Chinese newspapers, as these are the most likely to feature the more obscure, Mao-era, political terms often used in the HSK). I don’t always have time to dwell on their exact usage – and there are many words/phrases I have not yet heard in any real-world context – but I do get a little thrill when I hear a word or phrase which I have previously only known in the HSK context, being used out there in the real world.

In short, I try to undertake the (largely written) daily SRS drills in tandem with attempts to exercise my listening and reading skills.

My second and third flashcard decks are drawn manually from Chinesepod.com. I listen to lessons at the Intermediate and Upper Intermediate levels (keep up the good work, btw!:)) and, after each lesson, draw down new words/phrases into files which I transfer to my SRS system (Pleco, for what it’s worth). Thus I have an ‘Intermediate’ set, and an ‘Upper Intermediate’ set which are both increasing in size on a weekly basis, as new lessons are made.

My fourth flashcard set – and the most recent, and possible useful, addition – is a list of complete sentences which locates some of the most common/useful/interesting words/phrases in real-world context. I tend to take these sentences from the dialogues at Chinesepod.com, thereby ensuring that they are reliable in terms of how people really speak. This is an attempt to address the most obvious failing with SRS that it allows you to expand your vocabulary without requiring any understanding of how words are actually used in context. In this test, I look at the English translation and read out the correct Chinese sentence. The act of verbalising, if only to myself, seems to make certain patterns stick.

In terms of the specific tests that I undertake, I oscillate fairly systematically between, on the one hand, viewing the English translation and responding with the written Chinese translation (input using hanzi), while simultaneously verbalising the word in the (hopefully) correct tones; and, on the other, reading the Chinese word and verbalising the correct English translation out loud to myself. Regardless of the exact test I undertake, I try to be disciplined and have a rule for myself that if I could not, on request, write the hanzi that appear in the word, or if I get the tone of a character wrong (even if I knew how to write it), I mark the card as wrong. In some ways this is a vanity project – I want to be able to say (as I have been known to in the past) that “I am able to write everything that I am able to say”. On the other hand, as some other commenters have noted, writing a character over and over again does tend to make it stick in one’s memory banks.

As I mentioned, all of this takes me between 60 minutes and 75 minutes per day.

Despite all of my labours, I have concluded that while daily SRS work has enlarged my vocabulary and improved my reading skills (and to a lesser extent, listening skills), it has done absolutely nothing for my general conversational fluency. If anything, this is in a worse place now than it was nine months ago. I lived in China for several years in the Noughties (apologies:)) and, thus, feel confident in terms of my basic pronunciation and tones. But, here I am, nine years in, still finding myself jumping through all kinds of mental hoops and using torturous (and probably way overly complication and clunky) sentence constructions when it comes time to actually have a conversation at anything over a basic elementary level. Similarly, I have little confidence in composing a Chinese sentence in writing. I may be able to write the individual characters accurately, with the correct stroke order etc.etc, but I cannot necessarily link them fluently in a proper sentence, let alone a paragraph.

In summary, SRS is rubbish for improving fluency, but is great for developing vocabulary and thus (depending on precisely how it is used), improving one’s reading and listening comprehension. Luckily for me, right now I am most concerned with improving my Chinese reading skills, so this works for me. And I am (semi)confident that this is great foundational work for when I do, eventually, get back to China and find myself speaking with real people again (you currently find me residing in a sleepy English village – which, over and beyond everything I have said, is my biggest problem of all – the general ambient sounds in my everyday life are not those of Mandarin Chinese!)

Thanks for the detailed comment, Graham! At the time you didn’t know you were writing a guest post, so… surprise! I appreciate you going to the trouble of writing such a detailed account. Other learners will benefit from your ideas.

I like the way you diversified your SRS review, and your confirmation on the shortcomings of SRS as a study tool is helpful. There’s no silver bullet for mastery of any language…

22

Aug 2012Learn Chinese in 3D takes Chinese learning to the third dimension!

What does it mean to take Chinese learning to the third dimension? Well, it means a cool 3D interface for exploring Chinese characters and words, but beyond that, it’s not totally clear. But that’s OK! The way I view this new app, 3D Chinese, is a sort of experiment, a Chinese learning app that was created because it was possible. And I think that’s a good thing. It’s fun, for one (unless you’re a luddite). I’d like to see more of this kind of thing.

Check out the video and some screenshots:

I was a tester for this app, and I thoroughly enjoyed it. I gave the developer a few suggestions, and he was quite responsive to feedback. The style of the app still feels a little too Japanese to me, but it’s still a very polished experience.

So what is the app? Basically, it’s an alternative to a character dictionary or character book, where you have a bunch of common characters laid out in lists by radical. Instead, characters are grouped spatially by radical. You can explore the characters in the 3D environment, learn words containing those characters, etc. It’s a very visual, exploratory way to experience Chinese, and I know that appeals to a lot of people.

The app also has its own built-in SRS functionality. I didn’t test this functionality much, as the app seemed much more suited to a visual tour than the old “doing reps” SRS chore, but this feature might appeal to some.

3D Chinese is currently priced at $2.99. This is a reasonable price for its beautiful 3D visual experience, but this app is not for either (1) the super hardcore learner who wants extreme depth (that user really just wants a dictionary, not something visual-oriented), or (2) a super casual learner who just wants to be entertained by visuals and doesn’t really want to learn (the 3D effects of the app will lose their charm pretty quickly if the learner isn’t actually into the characters at all). If you don’t fall into either of those categories, and don’t find a price of $2.99 exorbitant, I recommend you give this little experiment in visual learning a whirl.

16

Aug 2012East Asian Bookshelf

There’s a new website out there designed to showcase study materials for Chinese, Japanese, and Korean. It’s called East Asian Bookshelf, and is introduced below by Dr. Li Minru:

> The National East Asian Languages Resource Center (NEALRC) at the Ohio State University would like to invite you to visit the website “East Asian Bookshelf” (http://bookshelf.nealrc.org), which aims to promote teaching and learning materials in Chinese, Japanese, and Korean and to assist teachers to find quality language teaching materials available to purchase.

> This project is a collaborative effort of NEALRC, CLASS (Chinese Language Association of Secondary-elementary Schools), CLTA (Chinese Language Teachers Association), AATJ (Alliance Associations of Teachers of Japanese) and AATK (American Association of Teachers of Korean), with financial support from a Department of Education Title VI grant.

There’s a pretty advanced filter in the lefthand sidebar to help you find the types of textbooks or other materials you’re looking for. It looks to me like the filter isn’t totally working yet, but I’m sure they’ll fix it. This is looking like a pretty useful resource.

14

Aug 2012CHONG: an ad for a flashcard

Every now and then I see something around Shanghai that feels like it were almost designed for Chinese learners, to put on a flashcard or something. Here’s the latest one (photographed near the Xintiandi Metro station):

The character is 宠 (CHONG), and it means “to spoil” or “to pamper.” You know, that’s the whole reason people get pets (宠物): they’re animals (动物) that they can totally love, dote on, and spoil (宠).

Obviously, this particular example is a bit over the top, and if it were a bit more up with the times, it would be an apricot toy poodle, clearly the current “fad dog” in Shanghai. You see these little dogs on the arms of girls all over the city, as well as in the photos of various types of social media.

(I think this city is due for a new fad dog, actually.)

09

Aug 2012Letter of Apology from the Shanghai Metro

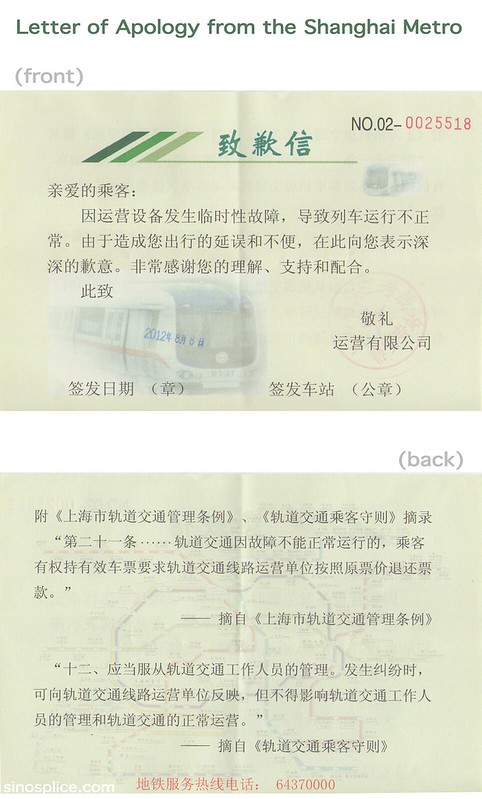

We were at the office today during Typhoon Day (hey, the last one was a total false alarm!), and one of my employees was late because the subway was running extra slow during the typhoon. She handed me this 致歉信 (letter of apology):

This was interesting to me, because I’d never seen something like this before. It’s pretty standard at many Chinese companies to require an official doctor’s note if you ever call in sick. But I wasn’t aware that there was a way to make the old “subway breakdown” excuse official. (Note that there is a serial number, a date stamp, and a hotline to call for verification. Super official!)

From a pragmatics standpoint, it’s interesting to me that it’s called a “Letter of Apology” when it’s clearly meant as an official form of “work tardiness excuse validation.” Now, if there were only a “my bus was late” letter of apology, we’d really be in business…

07

Aug 2012Better Chinese, Worse iPad Skills

I’ve heard some good things about a program for school kids called Better Chinese. Like many modern Chinese learning programs, Better Chinese is also on the iPad learning bandwagon. This screenshot from the website features the app:

Yikes! How’d they get a kid from the late 70’s to pose with that iPad, and why didn’t they tell him not to use a pen with that touchscreen?

I’m sure we’ll all figure out how to learn Chinese using these touchscreen tablets sooner or later…

31

Jul 2012How I Learned Chinese (part 3)

I started a series of posts all the way back in 2007 on how I learned Chinese. I began with how I studied before I came to China (part 1), and then continued with what I did after I got over here (part 2). That got me to a low level of fluency, sufficient for everyday conversation and routine tasks in daily life. But then what? What did I do to get past that level?

I didn’t continue the series past part 2 because it was obvious to me back in 2007 that I was still learning a lot of Chinese, and it’s never really clear what’s happening when you’re right in the middle of it (that whole forest and trees thing). Now, a good 5 years later, I’ve got a lot more perspective on the big picture of what was going on with my Chinese development back then. So it’s high time I continued the account…

Plateauing

After finally getting my Chinese to a point where I felt like I could honestly say “I speak Chinese” (sometime around 2003), I had to re-evaluate a bit. Wasn’t that my initial goal, after all? To get in, get fluent, and get out? And then move onto another cool and exciting country? Yes, that was my original plan: to be a bit of an “immersion whore.” It’s a dangerous game to play, though… because if you’re not careful, you might become emotionally attached. And that kind of affects the plan.

And I did get attached to my life in China. (I still find my existence here to be rife with an exhilarating kind of chaos.) And I still wanted to keep improving my Chinese. And I had met someone who might possibly be the coolest woman ever. Long story short, I had decided to stay.

Just as I had concluded that I needed real all-Chinese practice to improve my speaking in the beginning, I also realized next that I needed to increase the amount of Chinese in my life. Specifically, I needed a job where I could use Chinese, or possibly higher level studies in Chinese. I always enjoyed teaching English, but my duties as an English teacher conflicted with my personal goals of mastering Chinese. I had reached the dreaded intermediate plateau, that period where getting from point A to point B takes a long time and a hell of a lot of work, but it doesn’t feel like you’re making significant progress at the time. I needed a plan to propel myself beyond it, and my sights starting moving toward Shanghai.

It was at this point that I also came to the reluctant conclusion that I should probably take the HSK. I’ve never been a fan of standardized testing, and the HSK struck me then as particularly estranged from reality (and hasn’t gotten a lot better since). But the more formal Mandarin evaluated by the HSK could be useful in a work setting, and I had also begun toying with this new idea of going to graduate school for applied linguistics in China. You need an HSK score to get into Chinese universities.

HSK Ho!

The one-semester HSK prep course I took at Zhejiang University of Technology in the second half of 2003 was the first formal course in Chinese I had taken since arriving in China almost three years earlier. It reminded me that I hated studying to the test, but also that I really did have quite a few grammar points I still needed to nail down.

I recall clearly, before studying for the HSK at all, that I had some delusions of fluency, thinking that maybe I could go straight for the advanced HSK. My Chinese wasn’t nearly that good, though, and even after completing the course, I didn’t quite ace the HSK as I had hoped, although I got the score I needed for grad school in China.

Result: serious wake-up call! I still had plenty to learn. I had gotten good at the casual conversations I immersed myself in daily, but more of those conversations weren’t really helping me get to the next level (at least not fast enough). And although I had the HSK score I needed, I would still need to pass an essay exam to get into the applied linguistics program I was interested in.

Goals do help

So having studied for the HSK for about half a year and then passing it, I was ready for the next challenge: applying for graduate school in China. I learned that I needed to pass a hand-written essay exam on 现代汉语 (modern Mandarin), to prove that I had both the theoretical linguistic knowledge about the language as well as the Chinese writing skills to express myself. I was assigned a textbook to “learn” in order to pass the exam. The school directed me to the tutoring services of the student center, and I was able to hire a tutor to help me get through it.

What followed was a year of reading the textbook, discussing it with my teacher, and doing regular essay assignments. I directed my own studies and set my own pace, and my tutor (a college student) helped me along the way. Honestly, I barely even remember that year of study. I just remember writing a whole bunch of essays and seeing an awful lot of red ink. I also remember being quite surprised by how quickly my handwriting speed ramped up when I was regularly putting pen to paper with purpose.

When I finally took the essay test, I was super nervous, but all that writing practice paid off. I could bust out a decent length essay in the hour allotted. It wasn’t perfect (I think I got an 80%?), but I was in.

Remember that plateau?

The frustrating thing about the plateau is that you don’t feel like you’re making progress when you really are. It didn’t feel like my Chinese was getting significantly better as I acquired the vocabulary and grammar to pass the HSK, or even as I got steadily better at writing essays in Chinese. It’s not until well after the fact that you can look back on that period of time and realize that your skills really have progressed a fair amount since then. For me, it wasn’t until I was in grad school in 2005, pretty well adjusted after the first few weeks of classes, and thinking, “this actually isn’t so hard” that it finally hit me: wow, my Chinese has actually come a long way since those good old Hangzhou days.

For me, the key to getting through that intermediate plateau period was having a sequence of reasonable, attainable goals. I’m not sure I would have ever made it if my goal was just to pass the advanced HSK. I certainly wouldn’t have done it in order to read a Chinese newspaper. My long-term goal was earning a masters in applied linguistics in Chinese, but my first goal was simply getting a passing score on the HSK, which largely involved learning all the basic grammar patterns I had neglected (because I didn’t need them) and picking up the rather boring (but important) vocabulary I had formerly ignored. The half-year of working toward the short-term goal helped train me mentally for the next goal of passing the writing exam, and being able to switch gears from standardized testing to writing really kept things interesting. After those two smaller goals were attained, all that was left was a 3-year “make it through grad school” goal, which was a special challenge all its own, and a story for another time…