25

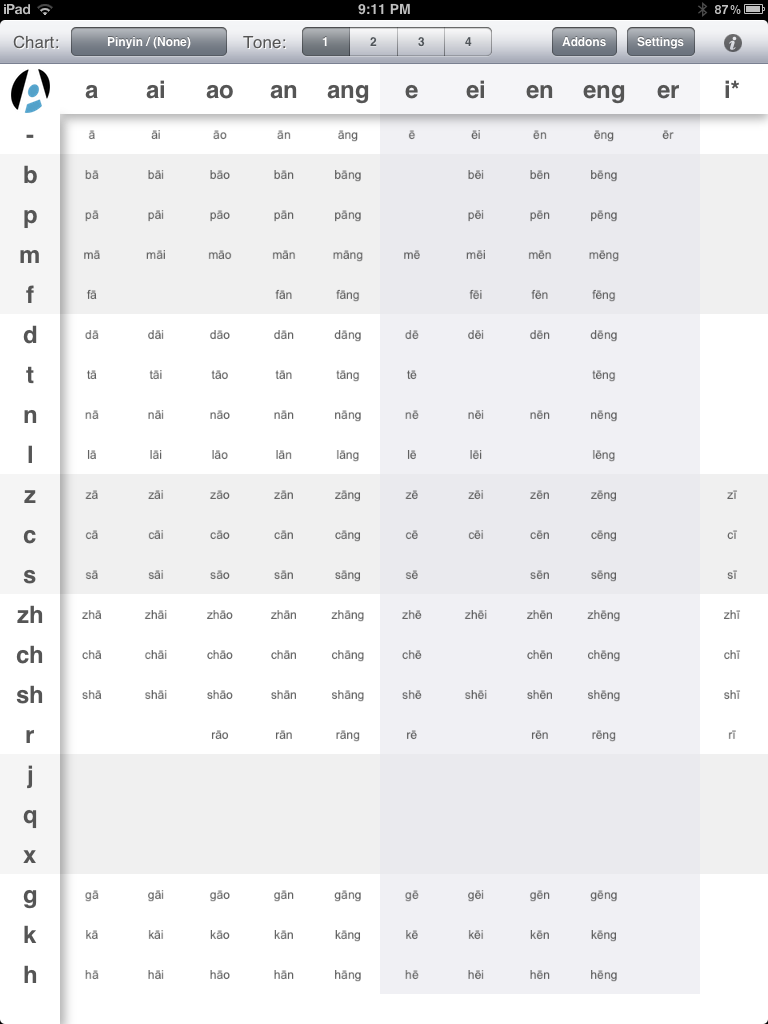

Jul 2012AllSet Learning Pinyin Chart: now with Gwoyeu Romatzyh!

Yesterday we released version 1.6 of the AllSet Learning Pinyin iPad app. We’ve been getting lots of good feedback on the app (thank you everyone, for the support!), and this latest release is just a small taste of some new functionality coming to this app.

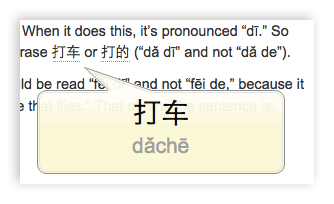

The major thing we added this time that all users can enjoy is the “play all 4 tones in a row” button. It works really well in conjunction with the audio overlay window (not sure what to call that thing semi-transparent rounded-corner box that pops up when you adjust volume on an iPad or play audio in this app). So not only are you hearing the tones, but you’re also seeing the pinyin text in big letters right in front of your face as it plays. The key point is that because the text is big, the tone marks are also clearly visible. (This can be a problem with some software.)

Aside from that, we also added four new romanizations to the chart as addons (click the links below to learn more about each):

The latter two are of interest mainly to Taiwan-focused sinologists. The first one is of interest to sinologists that like to poke around in musty old texts (the same types that are interested in Wade-Giles). The second one, however, is rather special.

Gwoyeu Romatzyh was invented by Chao Yuen Ren (赵元任), as legendary a linguistic badass as any that has ever existed. I won’t dwell on him in this article, but one of his accomplishments is inventing his own romanization method (Gwoyeu Romatzyh) which uses alternate spellings to indicate tones rather than tone marks or numbers. The idea was that tones should be an integral part of each Chinese syllable, not merely something tacked onto the end as an afterthought, and that binding tone to the spelling of each syllable is a way to enforce that.

Unfortunately, Gwoyeu Romatzyh (AKA “GR”) is a bit confusing. You can’t have regular alternate spelling conventions without running into conflicts, which forces a certain amount of irregularity, and well… it gets a little messy. It was definitely an interesting experiment, nevertheless.

While I would never considera using GR for any practical purpose, I do find that having GR on the AllSet Learning Pinyin chart breathes new life into the system for me, specifically as I play through the four tones of various syllables and watch the text update accordingly. Patterns start to emerge. Check out the following video, where I first play the syllable “shang” in pinyin (all 4 tones), then switch over to GR and repeat it, and then go through a whole slew of syllables in all 4 tones.

If you have an iPad, please be sure to check out version 1.6 of the AllSet Learning Pinyin app. Note that GR is available as an addon in the “Addons” section.

20

Jul 2012Bombing the Wall of Characters

Most Chinese learners have a goal of one day being able to read a Chinese newspaper, or a novel in Chinese. And thanks to better and better tools for learning Chinese, it’s getting easier to work towards that goal progressively. However, even learners who have studied for quite a while report that they still struggle with the “wall of characters” mental block. It’s that irrational, overwhelming feeling (perhaps even a slight sense of panic) we sometimes get when confronted with a whole page of Chinese text: the dreaded “Wall of Characters.”

No doubt, this fear is partly culturally rooted. From childhood, many of us have considered Chinese characters as roughly equivalent with the concept “inscrutable.” At times our brains seem to revert to that primitive, ignorant state where that wall of characters really seems impenetrable.

Nowadays, the “wall of characters” is often online, rather than printed on paper. We have all kinds of tools to help us chip away at the wall. Relative beginners, with the right training, can quickly start blowing holes in that wall, and with a little time and patience, the wall does come crumbling down at the feet of the motivated learner, leaving nothing but glorious meaning in its place. That’s a beautiful thing.

Today, however, I’d like to introduce a tool of a different sort. One that operates on the “primitive and ignorant” level of the “wall of characters.” It’s a “bomb” in a more literal (but digital) sense of the word, a toy called fontBomb.

I’ve found that applying fontBomb to the “wall of characters” is surprisingly satisfying, in the same way that smashing glass can be satisfying, and looks cool to boot. Here’s a video I made (sorry, YouTube only):

FontBomb is easy to use and apply to any page of text. Happy bombing!

17

Jul 2012New Hardware, Changing Study Methods

It’s striking how quickly technology is changing the way we learn Chinese. Recently I mused that it doesn’t seem to take as long to get fluent in Chinese as it used to, and one of the reasons I cited was technology. A recent Input Device Roundup update on the Skritter site calls attention to how it’s not just the software (“computers” in general), but actually the hardware that’s changing rapidly, and with it, the way we learn to write Chinese (with Skritter, anyway). Skritter’s in a unique position in that over the last few years, the service is seeing a big change in the types of hardware its users are using to interact with its service. From the humble mouse, to writing tablets, to tablet computers, Skritter’s a service that magnifies the impact of evolving hardware on learning Chinese.

Skritter Scott’s conclusion is that the iPad is now the best way to practice writing Chinese characters using Skritter. This doesn’t surprise me; last year I laid out some ideas for how really killer apps for learning Chinese characters could be created for the iPad, and lamented that no one had really attempted it yet. Well, we’re getting there!

If anyone’s seen some really interesting or innovative new apps for learning Chinese, please share. There’s so much potential…

12

Jul 2012The ChinesePod iPad App

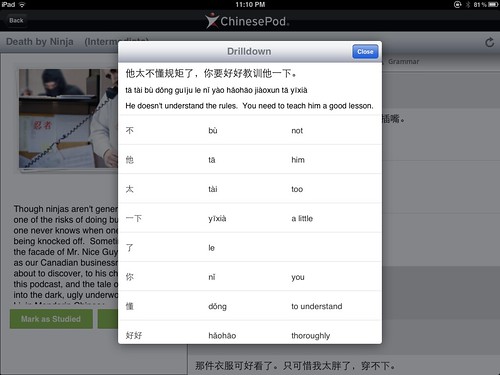

In June we got Skritter for the iPhone (finally!), and this month we at long last get ChinesePod for the iPad (subscription required). ChinesePod has had an iPhone app for a while, and that app has gone through some rough patches over the years, but with this new iPad app release, things are starting to look a lot better. The universal app which combines the iPad and iPhone versions (following the iPad app’s general design) is already in development and coming soon.

The newly released iPad app lets you access all lesson content (including your bookmarked lessons and the massive ChinesePod lesson archive), and you can also download all audio through the app (eliminating the need for further iTunes syncs).

Some screenshots:

It’s good to see this app out. I did a review of iPad apps for learning Chinese a while back, but the landscape is changing so rapidly that it’s already time to start completely from scratch! I’m happy that ChinesePod is joining the ranks of decent, modern iPad apps for learning Chinese.

Reminder: if you need an iPad app to help with pinyin, AllSet Learning Pinyin has you covered!

03

Jul 2012Creepy BenQ Marketing

These images are currently in the third “slide” of the BenQ USA website front page slideshow:

OK, military-themed FPS games are popular in the States. Especially with a tech-loving male audience. Fair enough.

But this is the third “slide” of the BenQ China website:

So… how, exactly, is this ad trying to appeal to a Chinese audience? Hmmm.

I don’t think these were meant to be compared.

29

Jun 2012How long does it take to get fluent in Chinese?

To answer this question, I’ll start by quoting from a Quora page, where two heavyweights gave excellent answers:

Mark Rowswell, AKA Dashan/大山:

When I started learning Chinese, I was horrified to hear that it would take me 10 years to become fluent. 27 years later I’m still working at it. Due to my work on television, some Chinese language learners may consider me a role model of sorts, but every day I’m reminded of what I don’t know and how much more there is to learn.

“Fluent” is a relative concept. I would summarize:

2 years to lie on your resume and hope no Chinese speaker interviews you for a job (because 2 years is enough to bullshit your way through a situation in front of non-speakers).

5 years for basic fluency, but with difficulty.

10 years to feel comfortable in the language.

David Moser:

The old saying I heard when I first started learning Chinese was, “Learning Chinese is a five-year lesson in humility”. At the time I assumed that the point of this aphorism was that after five years you will have mastered humility along with Chinese. After I put in my five years, however, I realized the sad truth: I had mastered humility, alright, but my Chinese still had a long way to go. And still does.

As the the above answers indicate, the notion of “fluent” is very vague and goal-dependent. Needless to say, the Chinese writing system does more than any other aspect to hamper mastery, to the extent that adult speakers must address the daunting problems of the script in order to function in the language. As an instructive metric, however, we can turn to the Defense Language Institute in Monterey for some rough estimates of the relative difficulty. They divide languages into different difficulty groups. Group I includes the “usual” languages a student might study, such as French and Italian. They estimate “Hours of instruction required for a student with average language aptitude to reach level-2 proficiency” (never mind what level-2 means) to be 480 hours. A further level is characterized as “Speaking proficiency level expected of a student with superior language aptitude after 720 hours of instruction”, which is “Level 3”, which apparently is their highest level of non-native fluency. Chinese is grouped into Category IV, along with Japanese. The number of hours needed to reach level two is 1320 (about 3 times as much as required for French), and the highest expected level for a superior student after 720 hours is only 1+, i.e. an advanced beginner. These are old statistics, but the proportional differences are bound to be similar today.

My own experience, in a nutshell: French language students after 4 years are hanging out in Paris bistros, reading everything from Voltaire to Le Monde with relative ease, and having arguments about existentialism and debt ceilings. Chinese language students after four years still can’t read novels or newspapers, can have only simple conversations about food, and cannot yet function in the culture as mature adults. And this even goes for many graduate students with 6-7 or 8 years of Chinese. Exceptions abound, of course, but in general the gap between mastery of Chinese vs. the European languages is enormous. To a great extent the stumbling block is simply the non-phonetic and perversely memory-intensive writing system, but other cultural factors are at work as well.

(David Moser is the guy who once explained why learning Chinese is so damn hard.)

My Own Experiences

I’m not going to go into the complex issues already covered above (and I should also note that my Chinese is nowhere near as good as Mark Rowswell’s), but Mark’s numbers seem fairly realistic to me.

Because I began my study of Chinese in the States, then moved to China and started practicing on my own pretty hardcore, I’d say I hit Mark’s “basic fluency” milestone at around 4 years of study. “Feeling comfortable” probably came after about 8 years, but I think my standard for “comfortable” is also lower than Mark’s. (I seriously doubt I am as comfortable now as Mark was after 10 years!)

What’s the deal?

It always pisses some people off when you say that learning Chinese is hard, or that it takes a really long time. In fact, it tends to inspire certain learners to go out of their way to prove that the opposite is true: Chinese is not hard, and doesn’t take long to learn. That’s fine; somewhere between the extreme views the truth can be found. But I’ve always found it important to have a realistic view of what you’re getting into, and getting someone like Mark Rowswell’s take on the question is certainly interesting!

It seems that some people are afraid that many people will be “scared off” if Chinese is too often represented as “difficult,” and that those that attain some mastery and then tell others that it wasn’t easy are simply jealously guarding their own perceived “specialness.” Personally, I started learning Chinese precisely because I viewed it as a serious challenge, and didn’t fall in love with it until much later. I’ve heard many times that Malay is really easy to learn, but that’s never made me want to learn it.

The Good News

The good news is that I truly believe that learning Chinese is getting easier, or that students are learning it faster than they used to. I’ve been observing this trend on my own anecdotally over the years as I meet ChinesePod visitors, as I meet new arrivals to China, as I take on new AllSet Learning clients, and as I work with new interns. The “Total Newb on Arrival” is getting rarer, tones are getting better, and some people are even showing up in China for the first time already able to hold a conversation. Nice!

I’ve compared notes with Chinese teachers abroad, and some teachers are making the same observations. One teacher told me that universities are having to restructure their Chinese courses because the original courses were not demanding enough, or didn’t go far enough. What’s going on here?

I think a combination of the following factors are playing a part:

- Kids are starting to learn Chinese sooner

- Chinese learning materials are getting better

- Technology is making learning characters (and pronunciation) less laborious

- Competition is naturally raising the bar

- Increased awareness about the Chinese language and culture make the whole prospect less intimidating overall

This is all very good news! And if this is a long-running trend that has been accelerating in recent years, it could also mean that while Mark Rowswell’s and David Moser’s accounts are totally truthful, it won’t be as time-consuming for you as it was for them because the difficulty (or time involved) to learn Chinese is depreciating, without us even having to do anything!

One more thing…

Oh, and let me also quote Charles Laughlin from the Quora thread, who replied:

Who cares how long it takes? Just do it! If you really want to learn Chinese, you will devote yourself to it however long it takes.

Very true.

25

Jun 2012Dueling Flavors

A friend of a friend recently opened a restaurant in Shanghai called 斗味.

That’s 斗 as in 斗争 (struggle) or 决斗 (duel), and 味 as in 味道 (scent, taste) or 口味 (flavor).

After dinner the other night, a friend was jokingly telling me that the name could be read 二十味 or 二十口未(口味). Ah, characterplay is always welcome… This particular example reminded me of Lin Danda (a timeless classic in character ambiguity).

斗味 is pretty good, and has very reasonable lunch specials, if you live way out on the west side of Shanghai. (It has a Dianping page, but is too new to have any reviews, apparently.)

Related: 味儿大

18

Jun 2012More Simple Chinese Signs

A while back I did a post on the simple characters around you. I’ve been slowly collecting some other simple signs. Here are three more.

Noodle to Noodle

In simplified Chinese, 面 can mian either “noodle” or “face.” 面对面 means “face to face,” hence the obvious pun. (Note: in traditional Chinese, the “noodle” character is written 麵.)

The other characters are 重庆, the city of Chongqing.

Big Big Small Small

大大小小 can means “big and small,” and can refer to both “all ages” as well as “all sizes.” Makes sense for a clothing store!

City West Middle School

市西中学 is sort of on the west side of the downtown Shanghai area (near Jing’an Temple, across the street from the AllSet Learning office). It’s one of the best middle schools in Shanghai. (I guess you don’t need a fancy name with obscure characters to be elite.)

12

Jun 2012Skritter for iPhone: finally!

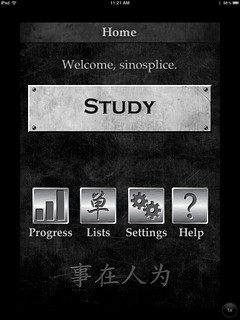

The hard-working guys at Skritter have been working on an iPhone app for quite a while. They put up a nice launch page, made a really cool video, and then… proceeded to “keep us in suspense” for a really long time. Well, the wait is finally over! Even though I’ve been helping to test the new app prior to the official release, I waited until I got word from Skritter that the app has been officially approved before writing this review. The app is real!

I’ve mentioned before that I feel the iPad has real potential for Chinese writing practice. I’ve always liked Skritter, but when Skritter first came out, I had already put in my writing time (the old-fashioned way), and I wasn’t really interested in using a mouse or a writing tablet to practice characters. It did strike me as a cool way for a new generation of learners to write, however.

With an iPad, though, it’s different. The iPhone is a little small, in my opinion, when my writing utensils are as big and fat as my fingers. That’s why I’m more excited about Skritter on an iPad than on an iPhone, and I actually tested the app exclusively on my iPad rather than my iPhone. (To be clear, Skritter has only released an iPhone version so far, so I was just running an iPhone app at 2X on my iPad.)

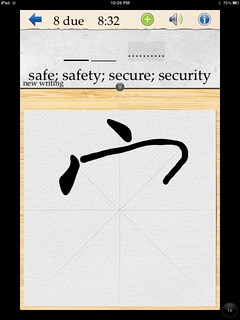

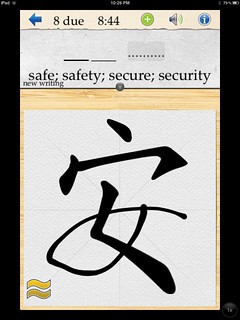

How is it? Although I’m not crazy about every aspect of the design, the app got one thing very right: writing is very smooth. And for this app, writing is the right thing to get right. (I’m pretty sure that makes sense.) They could have invested more into slick iOS interface design, but they chose instead to make the actual writing functionality of the app work really well. Good call.

I’ve only got screenshots here, but the “virtual ink” feels very liquid as you write, like it’s really seeping out of your fingertips. When you hold your finger down and make slower strokes, you can see the extra ink “flowing” out and sinking into the “paper.” I like it.

Here are a few screenshots of me fluidly writing my name (and then the ink fading). Meanwhile the Skritter robot wants none of my narcissistic tomfoolery, and reminds me in blue what I’m supposed to be writing.

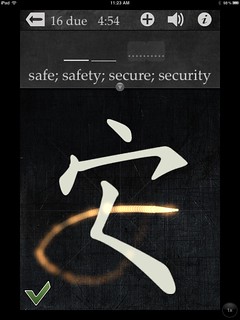

Here’s me writing the character 安. (And no, the Skritter robot doesn’t like strokes to be that connected, but hey, it made a cool screenshot.)

Here’s some crazy unacceptable strokes just straight-up exploding, and then a screen for tone recall:

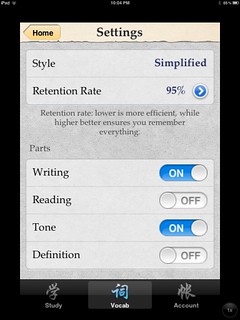

Here’s some word lists and a settings screen:

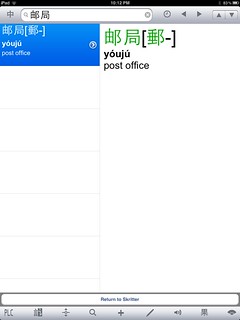

Finally–and this is a feature that kind of took me by surprise, because I’m a Skritter fan but not a regular user, so I was unaware of this feature before I discovered it–here’s a shot of Skritter’s Pleco integration. When you’re writing a word, you can click on the “info” button on top right, and then click on the Pleco button. That opens up Pleco, with the word already looked up. Pretty sweet! And there’s a button at the bottom of the Pleco screen which can take you right back to Skritter when you’re done.

Bottom line: very cool app. Yes, the free app requires a Skritter subscription to support it, so it’s not the cheapest option for writing practice. (But if you’re such a cheapskate, what are you doing with an iPhone, anyway?)

You can get the app here.

P.S. It wasn’t until after I had written this review that I bothered to ask Nick of Skritter why the styles in the video and in the app I tested were so different, so only then did I learn that you can change the theme of the app. I gotta say, I like the “Dark Theme” much better. The default theme is a bit of a “Peking Opera Mask” turnoff for me. I’m all for a modern China with modern Chinese.

Here’s the difference between the two:

Apparently a lot of people prefer the traditional “inky” style to the modern “flashy” style. Interesting.

P.P.S. If you’re interested in learning Chinese, though, make sure you’ve learned your pinyin first. AllSet Pinyin for the iPad can help with that.

29

May 2012Vancl’s “No Fear” Ad Campaign

Vancl (凡客) is a popular Chinese clothing brand that hires the likes of celebrity author/race car driver Han Han (韩寒) for its ads.

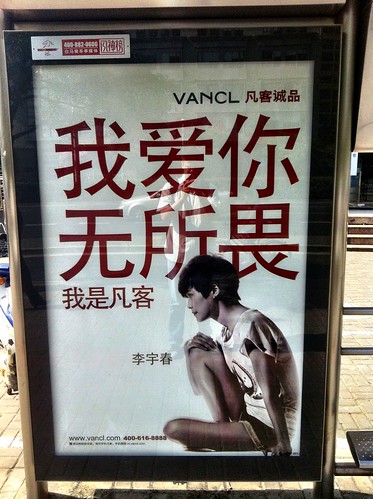

This ad featuring Li Yuchun (李宇春) is all over Shanghai right now:

On first glance, the Chinese in this ad is pretty simple, but doesn’t seem to make sense. 我爱你 means “I love you,” and 无所谓 means “don’t care.” Huh?

But look closer… It’s not 无所谓 in the ad, but 无所畏. The final character is different. So the meaning goes from “to not care” to “to have no fear.” The ad intentionally plays with you to draw you in; 无所畏 (“to have no fear”) is not a phrase you normally use in spoken language (although 无所畏 and 无畏 are not so hard to find online).

This ad featuring Han Han part of the same series:

Here you have the same 谓/畏 wordplay, this time introducing the phrase 正能量, a phrase popular among the kids which can’t be translated literally, and is used to mean something like “positive attitude.”

24

May 2012Learning, Not Spurning

The other day I went out with my wife, carrying my 6-month-old daughter. My daughter gets a fair amount of attention, and when we stopped to check out the DVD lady’s latest arrivals, a small crowd of Shanghainese ladies formed around us. They were quite interested in my daughter.

After all this time in Shanghai, my listening comprehension of Shanghainese has improved a lot, but I can’t say I’ve ever made a really concerted effort to learn it, and I still mishear things quite often. This was one such time.

One lady kept making the same comment over and over, which my brain sort of automatically filters through Mandarin Chinese. So what I heard, in only partly-applicable pinyin, was something like:

Hao bu xiang!

Now, 好 (hao) means “good,” but it can also be used as an adverb to modify an adjective, taking on the meaning of “very.” I know that the normal word for “very” in Shanghainese is 老 (lao), but I figured this was another way to say it.

不像 (bu xiang), of course, means, “not resemble.” So what I was hearing this lady repeating several times to my face, referring to the baby in my arms, was, “she doesn’t look at all like him!“

Kind of a rude thing for a stranger to say, no?

I’m not in the habit of replying to Shanghainese, though, and I know my comprehension of Shanghainese certainly isn’t perfect, so I just kept my mouth shut.

As we headed home, I asked my wife, “what were those ladies saying? ‘Hao bu xiang?‘ Were they saying my daughter doesn’t look anything like me?”

Her reply was, “no, of course not! They were saying, ‘hao baixiang,’ which basically means ‘very cute.'”

So then I felt pretty dumb. What they had said was:

Hao baixiang!

好 (hao) did, in fact, mean “good,” but 白相 (baixiang) is the Shanghainese equivalent of the Mandarin word 玩, which means “to play,” and 好白相 (hao baixiang) is Shanghainese for 好玩, which means “fun,” or, in this case, “cute.”

I knew the Shanghainese word 白相; I should have understood the comments. It’s good to be reminded what it’s like to be something of a beginner, making beginner mistakes. (It’s also good to realize that other people are not being jerks at all!)

P.S. I really didn’t know how to write the Shanghainese in this post… I didn’t want to bust out IPA, and using characters doesn’t seem appropriate either, but those are the characters used by the Dict.cn Shanghainese dictionary (which I linked to thrice above), and if you click through you get both Shanghainese audio (you need to hold the cursor over the audio icon, not click) and alternate non-IPA romanization.

21

May 2012Sinosplice Tooltips 1.2 is out

I continue to get questions about how I do the pinyin tooltips (popups) on Sinosplice. Well, let me remind you that anyone using WordPress can easily add this functionality to his blog. Just keep in mind that the tooltip content is manually added, not automatically generated.

The latest version of the plugin, 1.2 is available here:

You can also search and add the plugin through WordPress itself, and instructions on how to do that are here.

The plugin went through a rough patch recently due to some changes to WordPress’s edit screen code, making it difficult to add new tooltips to blog posts through the edit screen (although old ones continued to display fine). Now the editing screen “pinyin” button is working like a charm again.

18

May 2012A Chinese Perspective on World Gas Prices

The following data was taken from the March 27, 2012 issue of 星尚画报 (“Channel Young”) and reproduced with English translation:

| Country | Gas Price (USD/liter) | GDP per capita (USD) | Avg. Income (USD) | 100 L / GDP per capita | 100 L / Avg. Income |

| China | 1.4 | 4428 | 2356 | 2.94% | 5.52% |

| USA | 0.96 | 47199 | 38686 | 0.20% | 0.25% |

| Japan | 1.42 | 42831 | 39304 | 0.33% | 0.36% |

| Turkey | 2.57 | 10094 | 5242 | 2.55% | 0.49% |

| Norway | 2.444 | 84538 | 37994 | 0.29% | 0.64% |

| Denmark | 2.34 | 46915 | 28583 | 0.50% | 0.82% |

| UK | 2.145 | 36144 | 27809 | 0.59% | 0.77% |

| France | 2.132 | 40152 | 23229 | 0.53% | 0.92% |

| Germany | 2.132 | 39460 | 24321 | 0.54% | 0.88% |

| Italy | 2.353 | 33917 | 18783 | 0.69% | 1.25% |

Here’s the chart in its original Chinese:

| 汽油价格(美元/升) | 人均GDP(美元) | 人均总收入(美元) | 百升汽油/人均GDP | 百升汽油/人均总收入 | |

| 中国 | 1.4 | 4428 | 2356 | 2.94% | 5.52% |

| 美国 | 0.96 | 47199 | 38686 | 0.20% | 0.25% |

| 日本 | 1.42 | 42831 | 39304 | 0.33% | 0.36% |

| 土耳其 | 2.57 | 10094 | 5242 | 2.55% | 0.49% |

| 挪威 | 2.444 | 84538 | 37994 | 0.29% | 0.64% |

| 丹麦 | 2.34 | 46915 | 28583 | 0.50% | 0.82% |

| 英国 | 2.145 | 36144 | 27809 | 0.59% | 0.77% |

| 法国 | 2.132 | 40152 | 23229 | 0.53% | 0.92% |

| 德国 | 2.132 | 39460 | 24321 | 0.54% | 0.88% |

| 意大利 | 2.353 | 33917 | 18783 | 0.69% | 1.25% |

As you may have guessed, this article came out at a time when gas prices suddenly went up and caused quite a stir.

Of course, stats like GDP per capita and average income feel a lot more relevant to gas prices for countries where most of the population drives. It would be interesting to see this chart using “average income of drivers” instead of overall average income. You’d see a huge jump in the income column for China, but not as much of one for the USA.

(Oh, and yes, I’ve been meaning to post this for close to two months now…)

14

May 2012China Ammo for argumentum ad antiquitam

The summer between 7th and 8th grade, I went to a somewhat unusual “nerd camp.” I attended a 6-week “enrichment course” at the University of Tampa entitled “Logic and Critical Thinking.” We covered quite thoroughly the different types of logical syllogisms and logical fallacies. It was a singularly eye-opening experience for me, as many of the arguments I’d heard many times before were suddenly and for the first time exposed for what they were. In another sense, it was a new form of power. Adults rule the world, but they’re not above logic. Being able to identify logical fallacies in the arguments of politicians, teachers, and even parents was a potent little trick indeed!

Recently I read the book How to How to Win Every Argument: The Use and Abuse of Logic, which is basically a rundown of various types of fallacies, how to recognize them, how to defend against them, and even how to effectively employ them if you need to.

While a good read and quite entertaining in parts, many examples used in the book probably make more sense to a British audience than an American one. It also feels a little outdated at times, such as this passage on the argumentum ad antiquitam (“appeal to tradition”) fallacy and how it relates to China (links and bold added by me):

> Students of political philosophy recognize in the argumentum ad antiquitam the central core of the arguments of Edmund Burke. Put at its simplest, it is the fallacy of supposing that something is good or right simply because it is old.

>> This is the way it’s always been done, and this is the way we’ll continue to do it.

>> (It brought poverty and misery before, and it will do so again…)

> There is nothing in the age of a belief or an assertion which alone makes it right. At its simplest, the ad antiquitam is a habit which economizes on thought. It shows the way in which things are done, with no need for difficult decision-making. At its most elevated, it is a philosophy. Previous generations did it this way and they survived; so will we. The fallacy is embellished by talk of continuity and our contemplation of the familiar.

> […]

> Skilful use of the ad antiquitam requires a detailed knowledge of China. The reason is simple. Chinese civilization has gone on for so long, and has covered so many different provinces, that almost everything has been tried at one time or another. Your knowledge will enable you to point out that what you are advocating has a respectable antiquity in the Shin Shan province, and there it brought peace, tranquillity of mind and fulfilment for centuries.

Hmmm, “Shin Shan Province,” eh? The use of “province” in two different senses in one paragraph is a little confusing, but I would guess that “Shin Shan” is supposed to be “Shanxi” or “Shaanxi.” Anyway, I suspect that even when dealing in fallacies and tradition, it’s still a good idea to use the name of a province that actually exists.

It’s true, though, that China is still a treasure trove for bullshit purveyors of all kinds, whether it’s China’s mystical past, mystical writing system, mystical vocabulary (“crisis” = “danger” + “opportunity,” anyone?), or mystical traditions. I’m curious if my readers have run into many China-centered argumentum ad antiquitam fallacies out there.

11

May 2012Back to Jing’an (thoughts)

When I first moved to Shanghai, I lived in the Jing’an Temple area, behind the Portman Ritz Carlton Hotel on Nanjing Road. It was a cool place to start out my Shanghai experience, and I enjoyed my time there (even if there weren’t many good eating options nearby). I discovered the joys of Shanghai morning walks to work there, and the whole “familiar strangers” thing was interesting. Later, though, I moved to the Zhongshan Park area, where I’ve been living for about 7 years now.

photo by Neil Noland

Well, now that the AllSet Learning office has established its new office in the Jing’an Temple area, I’m spending a lot more time here, and really liking it. I can’t realistically walk to work every day anymore, but this area sure is nice to wander around in. I’ve also got new neighbors now, and it’s good to be able to more frequently see friends that live in this area. (If you live/work in the Jing’an Temple area and want to meet up and do lunch or something, get in touch!)

The move has been keeping me busy (and away from this blog), together with hiring new employees. Building my own team of passionate staff has been a really great experience, though. They say that when you start a new business, it never turns out how you expected, and while my business plan is going more or less as planned, the aspects that turn out to be the most challenging and rewarding have been surprising. Hiring, training, and building long-term relationships with Chinese staff have definitely been at the top of both the “challenging” and “rewarding” lists.

In 2007 I wrote two posts about “how I learned Chinese”: Part 1 and Part 2. I always intended to write a part 3, because I definitely feel that I’m still learning Chinese very actively after all this time, but have not yet written it because it was never clear in my mind what the next stage was, where it began, and where it ended (or will end).

It’s now clear to me that “Part 3” was grad school in China plus work at ChinesePod, and “Part 4,” a huge new challenge, is starting and running a business in Chinese. A kind commenter, after reading through this blog’s whole 10 year archive, has recently reminded me that I’ve written very few personal articles on Sinosplice lately, and that it sort of feels like something is missing now. Well, I’m planning on writing some thoughts on these experiences soon; and hopefully my readers will find them interesting or helpful in some way.

In the meantime, friends in Jing’an should hit me up… (and I’ll be getting caught up on my email soon!)

02

May 2012Peking Opera Masks

Recently Brendan put up a post called Peking Opera Masks and the London Book Fair on the new “Beijing Avengers” group blog, Rectified.name. It’s an insightful take on how contemporary Chinese literature is being represented (and not represented) abroad.

I especially enjoyed the explanation toward the end of his use of “Peking Opera masks”:

> A few years ago, a few other translators and I were talking with employees of a Chinese publishing house who said that they had some books that they wanted to translate into English — things that they said would show foreigners the real China. There was a brief and intense period of excitement, until the publishers said that these were coffee-table books about Peking Opera masks and different varieties of tea. Ever since then, I’ve used “Peking Opera masks” as mental shorthand for the Chinese habit of attempting to interest the world in aspects of itself that most Chinese people don’t give two-tenths of a rat’s ass about. (This same thing affects Chinese-language instruction, but I’ll save that rant for another post.)

Oh yes… you better believe that plenty of Chinese study materials out there are rife with Peking Opera maskery.

(Note: Just in case you have a burning desire to discuss Peking Opera masks in Chinese, these masks are usually referred to as 脸谱 or 京剧脸谱 in Mandarin.)

30

Apr 2012Mike Sui’s Video

A half-Chinese, half-American actor by the name of Mike Sui (Mike 隋) has been making quite a stir on Weibo and on the Chinese web with his recent video in which he plays the part of 12 different nationalities/personalities. He does various accents in both English and Chinese (and he’s clearly fluent in both). My favorite is the Taiwanese one (starting at around 7 minutes). Take a look if you haven’t seen it already:

(More details about the video and the Chinese reaction are on ChinaSMACK.)

Interestingly, the video is being promoted in a way that refers to him as a 老外 (foreigner), but Mike is clearly half Chinese, and speaks both English and Chinese natively (or very close to natively). According to various Chinese sources (here’s one), Mike’s dad is a Beijinger and his mom is American. That still counts as 老外?

25

Apr 2012Character Set Hodge-Podge

When I started studying Chinese at the University of Florida in 1998, we were allowed to choose to learn to write either traditional or simplified characters, but once we chose one set, we weren’t allowed to mix them together. Apparently the creator of this sign (spotted on 武夷路 in Shanghai) is not so restricted:

The text (as is):

> 外來車辆

> 禁止仃放

> 后果自負

> 245弄

The text in simplified characters:

> 外来车辆

> 禁止停放

> 后果自负

> 245弄

The text in traditional characters:

> 外來車輛

> 禁止停放

> 後果自負

> 245弄

If you carefully examine those characters, they should all make sense except maybe for this one: 仃 (停). It was part of the second round of simplified Chinese characters which was rescinded. (It still remains dear to the hearts of many “no parking” sign makers all over China, however.)

There’s more on 仃 at Sinoglot.

19

Apr 2012A New iPad App for Learning Pinyin

I’m very happy to finally announce that AllSet Learning has just released its first iOS app for the iPad, called AllSet Learning Pinyin. It’s a simple app, designed to take the typical pinyin chart we all start learning Chinese with and adapt it to the iPad. So that means supporting multiple orientations, as well as zooming and panning. And, of course, tapping for audio.

Last year AllSet Learning’s clients started buying up iPads at surprising rates, and all the beginners had the same request: I want a pinyin chart designed for my iPad. So that’s what we built.

More screenshots available on the product page

The app is free, and comes with not only audio for all pinyin syllables in all four tones, but also support for non-pinyin phonetic representations. So you can switch from pinyin to IPA, and even to other systems like Wade-Giles and zhuyin if you purchase the (very inexpensive) addons.

More addons for the app are coming. In the meantime, please try it out, tell your friends about it, and rate it in the App Store. Thanks!

Related Links:

– AllSet Learning Pinyin on the App Store

– AllSet Learning Pinyin on the AllSet Learning website

16

Apr 2012Sinosplice is 10 years old

It’s hard for me to believe, but the Sinosplice blog is already 10 years old today. My first post was April 16th, 2002. You can see 10 years of blog posts all on one page.

Through my early “China is so crazy” observations, to my English teaching posts, to my move from Hangzhou to Shanghai, through my Chinese blogging experiment, to my 3 years in grad school in Shanghai, to a stronger focus on Chinese pedagogy and technology, the only thing that’s really remained constant has been the “China” angle.

But what do I take away from the experience after blogging here for 10 years? Well, it was totally worth it. It wasn’t always easy to keep blogging all these years, but I’m totally glad I have. I frequently tell people that this is one of the single most rewarding activities I’ve ever devoted time to. It’s not that it was non-stop fun, or that it made me rich or made me into a great writer, but it’s connected me with people in ways I never expected. I met some of my best friends through my blog. I got my job at ChinesePod in 2006 through my blog. I’ve made many professional contacts through my blog, and it’s a great channel for new clients to discover my work at AllSet Learning. None of this was planned!

Nowadays blogging feels very corporate, or if independent, usually highly niche. When you look at the Sinosplice blog archive as a whole, it’d be hard say my blog is niche, because it’s changed so much over the years. Content, design, readers… it just keeps changing. I think a certain degree of flexibility with one’s theme is an important ingredient to keeping a blog alive long-term; when you’re overly focused you can write yourself into a corner and run out of things to say (or you just get bored).

So I’d just like to end this post by saying thank you to my readers, past and present, and to encourage those of you out there to put your voice online if you’re at all tempted. You don’t have to have an amazing start, and you don’t even have to be fiercely niche, but somewhere along the way you may find you have a lot to say, and keeping at it can really pay off in unexpected ways.