08

Oct 2008The Toilet Paper Excuse

My friend Sean has a hilarious post up about cultural differences compounded by generation gaps in China. This particular drama revolves around toilet paper. Here’s an excerpt:

> By the time the night was finishing up and the massage was over, it was quite late, around 10:30pm. The parents live in a slightly remote part of Shanghai, only accessible by bus or taxi, and they always refuse to take a taxi because its too expensive (even if I offer to pay). I told JJ to tell them to just stay the night at our house, that made the most sense and it was totally fine by me (and of course by JJ). We do have an extra room and I did buy this couch bed for this very reason. So it only made sense for them to stay, especially since it was holiday and JJ was not working.

> Here comes the kicker. They were at first totally against it. Why, you might ask? Well it was not for the normal reasons you might imagine, such as ‘we don’t want to intrude’, ‘we have plans tomorrow morning’, we simply want to get home’, ‘we don’t like the couch bed’. None of these things mattered to them. Instead, the issue at hand was literally:

> We don’t know if we want to stay because the toilet paper I buy is too soft for them and they really don’t like using it.

Read the rest of the post for Sean’s reaction.

The type of “toilet paper” the parents prefer is called 草纸 (literally, “grass paper”), although it’s sometimes just referred to as 手纸 (which, amusingly, are the same two characters used to write the word for “letter” in Japanese).

I used to use 草纸 as paper towels back in the day. I tried to find a decent picture of it online, but this was the best I could do.

06

Oct 2008DVD Waste

Cheap DVDs are one of the well-known perks of living in China. For roughly $1 per disc, you can buy almost any movie or recent TV series. There’s a huge market for this form of entertainment, and it creates two significant forms of waste material.

Packaging

Some of the Chinese DVD vendors are using enough packaging these days to make even the Japanese blush. A recent DVD purchase of mine revealed the following layers of packaging:

1. Cellophane wrap

2. Cardboard display sleeve

3. Plastic box

4. Paper envelope

5. DVD sleeve case

6. Flimsy plastic sleeve

…and inside that was the actual DVD. The Chinese vendors are getting more elaborate with their packaging than the real (unpirated) DVD sellers. Why? Almost all of it goes straight into the garbage, and while some of the packaging may look good on the shelf, I can’t see the need for 6 layers of it.

Disposability

These pirated DVDs are essentially as disposable as a magazine. After one view, you might be ready to get rid of it, but if you want to keep it, you can.

I remember when I first came to China I thought that every DVD I was buying was going into “my collection.” Well, you don’t have to be here long to realize that your collection will very quickly grow beyond manageable size if you keep everything you buy. And clearly not every DVD you buy is worth keeping, even if the picture quality is excellent.

So now after I watch a DVD, if it’s not deemed worthy of keeping (and most aren’t), it goes directly into the “bag of crappy DVDs.” I usually just end up giving that bag to my ayi. Not sure what she does with them.

How about you? What do you do with your unwanted DVDs? It’s a strange problem to have, but when I look at the amount of DVDs that are bought and sold on the streets of China, I’m reminded that it must add up to an awful lot of DVD waste.

04

Oct 2008Hand-written Menus

Micah posts some scans of an attractive hand-written menu for 老克勒.

[link to full size]

[link to full size]

Note: the names of the dishes (and most of the prices) are in orange.

As I mentioned in my Black Back post, I think learning to read hand-written Chinese is an important skill that’s not emphasized in textbook/classroom courses. Here’s a chance to work on that skill while also learning dish names (another common difficulty for the recently arrived).

03

Oct 2008Lisa Movius on the Shanghainese

Lisa Movius, an American that has been in Shanghai for almost 10 years, has written up some thoughts on the local language and culture in her post, Beleaguering the Shanghainese.

Some excerpts:

> I also no longer think that Shanghainese are snobby. Somewhat, and some of them are, but not hugely more than anywhere else. The Shanghainese are proud, and they are defensive. That a scruffy, disparate batch of immigrants and refugees could have fused such a coherent urban culture in the face of foreign colonialism and domestic disdain is amazing. As is the fact that their identity is positive and optimistic rather than a dark bunker mentality, given the endless attacks upon “Shanghaineseness”.

And regarding spoken Shanghainese:

> I remember early weeks in Shanghai overhearing a conversation in Sangheiwu [Shanghainese] between two colleagues. Afterwards, I asked what they were arguing about. “Arguing? We were saying what a nice day it is today!”

Read the rest of the post for her thoughts on a ChinaSmack post.

Lisa also links to the Sinosplice Shanghainese Soundboard and asks for more resources. I’ve covered the textbooks before, but if you’re interested in video lessons intended for Mandarin-speaking Chinese, you can find those online as well:

– 学说上海话 (a playlist of lots of lessons)

– 上海话三月通 (another playlist of different lessons)

– Titanic in Shanghainese (more for entertainment than educational value)

01

Oct 2008Shuirong C100

In the last few weeks a new drink has appeared on the convenience store shelves of Shanghai. It’s called 水溶C100, but you probably know it as “lemonade.”

The name 水溶C100 comes from the idea of 水溶性维生素 (water-soluble vitamins). In this case, obviously, it’s vitamin C, and the drink boasts 100% of the recommended daily dose of vitamin C (the equivalent of 5.5 lemons, the bottle tells us) in each bottle… but only 12% juice.

I like the drink well enough. Seems to be another success for bottled water company Nongfu Spring, the same company that pleased me 5 years ago with it’s “Farmer’s Orchard” juice. But this new product has been given a fairly horrible name. My wife, who’s been drinking the stuff for a few weeks (like me) still has no idea what it’s called if she’s not looking right at the bottle. It’s just “that lemon drink” (什么100?). And what should we call it in English? C100? I don’t even know. And not only does it have an unmemorable name, but there’s that awkward word in big print “lemon,” just hanging out on the label, though apparently not part of the name. Thanks. Lemon. (But only 12%!)

The drink is quite strong (sour/sweet), but I find it mixes nicely with tonic water, creating a classy concoction remarkably similar to Japan’s own CC Lemon (now there’s an Asian lemonade with a catchy name!). I bet this stuff mixes great with vodka as well.

25

Sep 2008The Last 7-Day Workweek?

It’s that time of year again: vacation absurdity time. Most people in China have to work this coming Saturday and Sunday in order to “make up for” the seven vacation days in a row to come.

Last week was only a four-day workweek (preceded by a three-day weekend), and now this week it’s a seven-day workweek. It’s like jetlag for workweeks; we’re going to need those seven days off to get over the messed-up schedule.

There’s talk of scrapping the October week-long holiday (and its accompanying seven-day workweek), just like the May holiday week disappeared this year. I’m really hoping it happens.

22

Sep 2008Micah and John on Touring Shanghai

Blogger Matthew Stinson recently asked Micah and me about what there is to do in Shanghai. I thought the conversation might be useful to some readers, so here it is, edited somewhat:

Matthew asked:

> I’m heading down to Shanghai for National Day [October 1st]. I have rather bizarrely never actually been to Shanghai before, so I was wondering what places you’d recommend I visit and what places you’d recommend I avoid during my time there. I have about 3.5 days to wander around the city.

> Also wondering what district you recommend getting a hotel or hostel in.

Micah replied:

> Three and a half days is enough to see all the major attractions and then some. However, a disclaimer: sometimes I get too gung ho about the city, so if John’s recommendations clash with mine then trust him over me.

> For a hotel or hostel I’d recommend staying close to People’s Square, which is a good launching pad for visits to just about anywhere in the city because it’s the location of the subway Lines 1/2/8 interchange. I have two places in mind, depending on your budget. If you’re going cheap, stay at the Shanghai Mingtown Etour Youth Hostel. It’s just west of People’s Square, next to the quaint little pet market where I buy chinchilla food and the Shanghai Art Museum. It’s also a short hike away from Suzhou Creek, a good place for photography. If you’re willing to pay RMB 200-300 for a standard 标准间 hotel room, the 上海市工人文化宫东方宾馆 (Shanghai Worker’s Cultural Palace Far East Hotel?) is right on People’s Square, 2 minutes from the subway, in a historic building that’s now being used as a civic center but has a hotel on the upper floors. I tried to book it for my parents when they came for our wedding two years ago, but they were renovating at the time so now it must be even nicer now. Either place, call in advance and confirm rates/availability, of course.

> Whoa, that was way too long. I’ll keep the “tourist attractions” in list form:

> DO

> – Yu Gardens area (for the food and the antiques)

> – Taikang Road (trendy fixed-up old neighborhood)

> – People’s Square + Nanjing East Road + Bund (don’t mind the scammers, just chat them up and then brush them off)

> – Shanghai Museum (on People’s Square)

> – Lujiazui area (Aquarium, World Financial Center, Super Brand Mall)

> – Jing’an Temple

> – Yuyintang (this is a good live music venue, if you’re into that)

> – Science & Technology Museum

> – Wander around the French Concession area

> – Wander around the Old City (north from Dongjiadu)

> SKIP

> – Yu Gardens themselves

> – Shanghai City Planning Museum

> – Longhua Temple

> – Anything else in Pudong besides Lujiazui and Sci-Tech Museum

John replied:

> Heh, I always panic a little when people ask me about things to do in Shanghai. While I do like the city, I don’t feel like there’s really that much for visitors to DO when compared with a city like Beijing. This city is about business, shopping, dining, and nightlife!

> Still, it’s not fair to say Shanghai has nothing to offer, and I think Micah did a pretty good job of listing the attractions. I’ll just add a few comments to Micah’s list.

> HOTELS

> I’m sure Micah’s suggestions are great, but don’t forget the traveler’s favorite: The Captain’s Hostel. It’s probably been booked solid for weeks, but you might still want to check it out.

> DO

> – I’ve never been a fan of Yu Gardens; feels like it’s just for tourists from abroad. So while I would expect my parents to enjoy it, I wouldn’t expect you to.

> – Jing’an Temple is cool-looking, being right in the middle of the city, but don’t bother going in. The park across the street is quite nice, though, and both New York Pizza and Burger King are right there if you’re interested.

> – I went to the Science and Technology Museum with my wife last year, and we were both disappointed. We found it too child-oriented, run-down, and outdated.

> – You might consider the Xujiahui Computer Market (there are actually two separate markets right in 美罗城, plus a BestBuy nearby), and I hear there’s a photography market near the Shanghai Train Station that has lots of cool stuff for photo buffs [Editor’s note: Brad tells us that photography market is now closed].

> – Micah left off Xintiandi, a major tourist highlight. Yeah, it’s all fake and expensive, but I think it’s an important side of Shanghai. To me, Taikang Lu doesn’t feel much less fake… at least Xintiandi is honest about what it is. (Sorry, Micah!)

> – Check out the Liuli Glass Art museum on Madang Lu (right next to Xintiandi). Really amazing stuff by a Taiwanese artist, with a Buddhist theme. Make sure to go in early afternoon; it turns into a bar at night, and the exhibits go away.

> EAT

> To me, you’re missing one of Shanghai’s major highlights if you’re not here to EAT. Shanghai cuisine might be a bit sweet, but there are plenty of excellent restaurants, and tons of variety (both domestic and international). With a little planning, you could be eating one mind-blowing meal after another, if that’s something you’re interested in.

Micah replied:

> In re: to John, I totally agree that there’s just not that much to *do*. Go out to eat a lot, have a massage, get some clothes tailored, climb the Pearl Tower… that’s the extent of what 90% of Shanghai tourists do because Shanghai is about quality of modern life, not so much about history or cultural production.

> No comment on Xintiandi. I’m “against it” in theory, but I haven’t been there in ages and I’m not really familiar with the area. I believe John used to work near there, so he would know better than me.

> Finally, John, I was trying to think of a Shanghainese place to recommend because it’d be a shame not to eat the local cuisine no matter how people from outside of Shanghai bad-mouth it. But I was coming up a blank — the best places I’ve eaten are hole-in-the-wall, out of the way, or too expensive to recommend with a clean conscience. Can you name a place off hand?

John replied:

> You mention the Pearl Tower, but you didn’t put it in your “DO” list. I’ve actually never done it myself. Is that another one that should be on the “DO” list?

> Not really sure about a good Shanghainese place… There’s so much fusion going on that I don’t really worry about where the food is supposed to be from too much.

> Matthew, you might browse the restaurant listings on smartshanghai.com for the expat view, and on dianping.com for the Chinese view.

Micah replied:

> The Pearl Tower is the no-brainer, average-Joe view of Pudong. The Jinmao Tower’s 88th floor observation deck is the more sophisticated option. That one lounge on top of the Jinmao Tower where you pay the bar’s cover charge to enjoy the view *and* a classy drink is the savvy-traveler’s choice. But the only view that made it onto my DO list is the new World Financial Tower, because it’s NEW and higher than all the others (though I hear it’s a bit pricey).

> If I was playing tourist, maybe I’d go to Din Tai Fung. Even though it’s Taiwanese it wins all the contests for Shanghai 小笼包, and I betcha they have more Shanghai dishes than just that. Dianping has them at RMB 100 per. Jodi and I got invited to a birthday party at 福1039 on Yuyuan Rd by a Shanghainese friend, very 本帮 [local Shanghai] and set in a semi-fixed-up colonial era home, but a little out of the way and RMB 200 per on Dianping.

> And yeah, seconding smartshanghai and dianping.

Readers: Any other recommendations for good, reasonably priced Shanghainese food, or must-see parts of Shanghai?

19

Sep 2008Love, Change, Tian'anmen

Images brought to you by Marco of ItalianPod fame (and also the artistic eye behind ChinesePod‘s recent videos).

17

Sep 2008This Mascot Hell is Just Beginning

Few would dispute that Beijing pulled off a very successful 2008 summer Olympics. Still, if you wanted to argue that there were five little flies in that craptaculicious ointment, they would be these guys:

The Fuwa (福娃). They’re lame.

Even the Beijing Olympic Committee seemed to get it… the Fuwa did not figure largely in the various displays of “China is so awesome.”

Now, as the Fuwa awkwardly fade into obscurity, Shanghai has to deal with a mascot far more horrible: Haibao (海宝). Yikes.

If you’re really a glutton for punishment, this song and video from the Shanghai 2010 World Expo website will have you cringing in no time.

It doesn’t stop at Haibao, though. Over the weekend, I found out that there’s a Shanghai Shopping Festival (上海购物节). Its very existence is absurd, but the worst part is that it has two more bad mascots: Kaikai (开开) and Xinxin (心心).

I’m not sure why China has decided to unleash this mascot hell upon us, but I have a sinking feeling that it has only just begun…

15

Sep 2008Jobs and Internships at Praxis

Just a quick note about some open positions with the company I work for, Praxis Language (the ChinesePod people):

– ChinesePod Product Manager. Help keep ChinesePod running smoothly, while contributing to the best Mandarin lesson on the net. Managerial experience, Chinese ability, and insight into education required. Full-time position in Shanghai.

– ChinesePod Interns. Participate in the community and help us improve the product. Great for students of Chinese in Shanghai, as we can be flexible about the work times. Part-time position in Shanghai.

– FrenchPod Lead Teacher. Help make the best podcasts for learning French. Teaching experience and fluency in French required, but you can’t be a native speaker of French — this teacher needs to have the learner perspective. Full-time position in Shanghai.

E-mail me if you’re interested in applying. Thanks!

09

Sep 2008Shanghainese Does Saint Seiya

Remember that Indian music video subtitled with hilarious similar-sounding English lyrics? Well, here’s something along the same lines, only with Japanese and Shanghainese.

The video is the theme song for a Japanese anime series called Saint Seiya (圣斗士星矢 in Chinese — apparently it’s well-known among the Chinese). This case is a little different, because the song was actually re-recorded with (ridiculous) Shanghainese lyrics. (In a karaoke parlor, from the sound of it.) And there are subtitles for us Shanghainese-impaired! The kind subtitler put the Shanghainese “transliteration hanzi” on the top line, and the Mandarin translation on the bottom line.

Here’s a quick and dirty translation of the lyrics:

> No hot water for washing my feet

> Today I’ll go to bed without washing them

> The water for washing my face is still heating up

> Going to bed without washing my feet – so dirty

> No hot water for washing my feet

> Mom says the bills are too high

> She says wash your face first, then use that water to soak your feet

> Water for your feet and water for your face

> They’re both heated with the gas burner

> Why don’t salaries go up? The cost of water, electricity, and gas have

> Oh my God

> Heat it, heat it*

> If you don’t heat it, the price’ll be higher next year

> Heat it, heat it

> Wash you feet, then go for the spa, oh yeah

> Heat it, heat it

> Heat it from now til the end of the month

> Heat it, heat it

> Why not heat it?

> My mom is paying the bill

Lots of great cultural context here:

– Water in Shanghai has traditionally been heated with gas heaters (although electric ones are also common now)

– Traditional Shanghainese good old-fashioned thrifty living

– Washing one’s face and feet traditionally has been a common substitute for taking a shower

Here’s the original Japanese theme song.

The Shanghainese version of the video was recommended to me by a local friend who said the Shanghainese lyrics sounded like the Japanese. I don’t really hear the resemblance, but it’s good wacky fun nonetheless.

*Any resemblance to Beat It is unintended.

07

Sep 2008Denison Witmer for English

Some selected lyrics from Denison Witmer‘s song “Are you a Dreamer?“:

> Dream, are you a dreamer?

> Are you a dreamer?

> Do you dream?

> Sleep, are you a sleeper?

> Are you a sleeper?

> Do you sleep?

> […]

> Love, are you my lover?

> Are you my lover?

> Do you love me?

> Save, are you a savior?

> Are you a savior?

> Will you save?

As a linguist with experience teaching English, my reaction was, this song could be good material for teaching simple derivational morphology and question forms.

(Of course, on a personal level, my reaction was, I need to listen to some punk to balance out this Denison Witmer stuff…)

03

Sep 2008Failed Humor Begets Violence?

I read this article on Discovery.com last week: Telling Bad Jokes Invokes Hostility, Violence. It prompted me to reflect upon my struggles with humor in foreign languages, and in English too.

Random observations:

– The more familiar I am with the people I am with, the funnier I am. Thus, in my nuclear family I am a comedic superstar, while at work or when meeting people for the first time, not so much. Other friends fall somewhere in the middle.

– I never got very fluent in Spanish (and I’m definitely not at my high point now), but I never felt it was very hard to make jokes in Spanish. In general, the humor translated well across the cultural gap.

– It was verrry difficult to be funny in Japanese. Granted, I only lived in Japan for a year, so I wasn’t super fluent, but I repeatedly made efforts to be funny in conversations with friends, and I crashed and burned a lot. My homestay brothers mocked my failed attempts rather mercilessly. (Their cries of “さぶっ!” still haunt me.)

– It was kind of hard to make jokes in Chinese, but I never felt as much pressure to be witty as I did in Japanese. Furthermore, failed humor tends to result in confusion or non-comprehension rather than mockery.

– Even when I make a bad joke in Chinese, rarely does anyone call me on it. The exception, of course, is my wife (one of the funniest people I know), who dutifully reminds me that in Chinese, I am not very funny.

Based on my experiences, it seems like familiarity raises the stakes in humor. When you tell a joke to someone you’re close to, you either score big, or you lose big. And losing big can mean violence (according to the study)?

But I’m guessing that’s pretty cultural. I’m not at all surprised that it’s hard to be funny in France. This is a great quote from the article:

> “I may have been Nancy funny, but I was not French-speaking-Nancy funny,” she said.

I’m curious if any readers have had “violent” reactions to bad jokes in Asia.

Related: When Humor Runs Aground, Dumb Joke [on ChinesePod]

31

Aug 2008The Chinese Shoryuken

Here’s another illustration from Black Back’s book, 我们丫丫吧:

Two nice pop culture references there, but interested in Chinese onomatopoeia as I am, I can’t help but fixate on the Street Fighter sound effect label: 欧由根. This especially amuses me because I remember when I was playing Street Fighter II in high school, my friends and I could never quite agree on what the heck Ryu was saying. We always thought it was something like “Har-yookin,” but apparently at least some of the Chinese hear it as “oh-yoogun.”

For those of you who have no idea of what I’m talking about, or only a very fuzzy recollection, this video, taken directly from the Street Fighter II video game, has plenty of sound bites for you:

Anyway, curious, I Baidu’d the phrase and, on a page about 我们丫丫吧, found some interesting stuff. I couldn’t help trying to decipher these:

– 欧由根: the classic shoryuken in the illustration above (see 0:11, 0:12, and countless other places in the video)

– 啊卢给: Hmmm, either it’s a hadouken (0:08), or it’s someone else’s move. (Anyone…?)

– 加加不绿根: the hurricane kick (0:54)?

If you’re Chinese and you used to play Street Fighter II, I’d love to hear what you used to hear the characters saying.

[Sorry for the excessive early 90’s nostalgia. All you people that liked the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtle post, this is for you!]28

Aug 2008Black Back Comics: Chinese Manga for the QQ Generation

Recently at a Family Mart convenience store I encountered 黑背 (“Black Back”) comics, the creations of Zhang Yuanying (张元英). I’ve been a fan of independent comics for a while, but I’ve had trouble finding much I like in China. The main thing that has turned me off of mainland Chinese comics is their highly derivative nature. They all seem like copies of Japanese manga! Not 黑背, though. While it does borrow some elements from Japanese manga, it has its own simple style. And it’s definitely darker than the comics of Zhu Deyong (朱德庸), the wildly popular Taiwanese cartoonist.

Apparently 黑背 gained popularity on Tencent’s QQ community through the author’s blog. Here are the three 黑背 books I bought:

我们丫丫吧

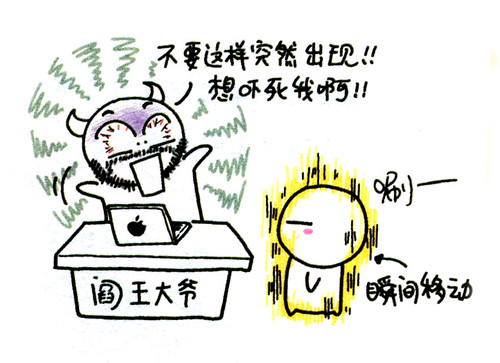

A very morbid little book about suicide. It’s basically a guide to suicide in comic form, going through all the various possible methods, rating them according to various factors such as pain, chances of success, consequences of failure. Each section has a little “commentary” at the end using recycled art reminding you why suicide is actually a bad idea, which I’m 100% sure the editor (or censors?) demanded be added in so that the book can’t be seen as totally condoning suicide.

OK, so I like Edward Gorey; I can deal with morbid illustrations and themes. What I really can’t forgive, though, is that the comic just isn’t very funny. I guess I did learn some new suicide-related vocabulary from it, but I hope that never comes in useful. I have to admit, though, that the Mac-using devil character amused me.

Also, after reading most of the book, doing Google and Baidu searches, and asking several Chinese friends, I’m still not sure what the 丫丫 in the title means. That annoys me.

宅男宅女私生活

I guess this one is semi-autobiographical. We learn about the married life of the young artist, in comic form. It’s kind of cute, and definitely less morbid than the other book. Unfortunately, it’s still not terribly funny.

Here’s an example of a simple strip:

Again, I like the art, but the “gag” is only good for a smile at best. It caught my attention for its use of the term 河蟹 (river crab), a pun on the term 和谐 (harmonize).

黑背读奥运

I was completely surprised to discover that this book was by far the most entertaining of the three. It seems that the most work went into it (wonder why??). The book gives a humorous history of the Olympics, then goes on to give comic commentary on each event. It ends with some lame pro-Olympics propaganda (seems this book was 河蟹d as well).

This is probably my favorite drawing from the book, illustrating the great variety of foreigners flocking to the Beijing Olympics:

The Value of 黑背

Like I said, I like the style of art. It’s cute and fun, but dark at times. That’s a big plus for me. Unfortunately, 黑背 is not terribly funny (Zhe Deyong is far, far funnier), but the Olympic book showed me that there’s some promise there.

I think that the handwritten Chinese characters are a good form of reading practice for a learner of Chinese. Very few Chinese study materials prepare learners for handwritten characters. While the characters in these comics don’t look like typical Chinese handwriting, the variation will still be good practice in stretching basic character recognition ability.

As for vocabulary, the intermediate (and even elementary) learner should be able to read much of 宅男宅女私生活 (see example above), but the others will pose more of a challenge.

25

Aug 2008Buying an iPhone in Shanghai

The first time I went to Xujiahui looking for iPhones, I didn’t have much luck. All the shops told me they didn’t carry 水货 (smuggled goods). Later, Brad tipped me off about exactly where to go in the computer market, and when I actually bought the iPhone about a week ago, the iPhone seemed to be for sale everywhere.

The place to buy the iPhone in the Xujiahui computer market is B1 (don’t waste your time upstairs). There are actually two computer markets in Xujiahui (both accessible from the subway); both are selling the iPhone in B1. I recommend the one connected to the big glass globe; there’s more selection/competition. The iPhone 3G can be found, but it’s quite expensive. I didn’t pay much attention to its selling price because the iPhone’s new 3G capabilities are useless in China. Instead, I sought out the original iPhone. The 8 GB version can be bought for around 4000 RMB, and the 16 GB version for 5000+ RMB. I opted for the former.

It can be confusing shopping for the iPhone because of the disparity in vendor prices, and when you try to find out why, you get all kinds of stories. I didn’t see anything that looked like a knock-off, but you definitely have to make sure that the iPhone is undamaged and comes with everything it’s supposed to.

My employer, Praxis Language, is a leader in the field of mobile language learning, so it strongly encourages key employees (in the form of a nice subsidy) to get iPhones. I bought mine with some co-workers on a “company field trip,” and we tried to get a 团购 (“group shopping”) discount. I was quoted a price as low as 3500 per iPhone by one vendor, but we ended up paying 3900 per and going with a vendor that seemed more trustworthy. A telling exchange:

> Me: Your iPhones are all opened.

> Him: Yeah, we have to open them.

> Me: But that shop over there sells them unopened.

> Him: They just re-shrink-wrap them. If you want me to, I can re-shrink-wrap one for you too.

This kind of candor sold us on the vendor. He was also happy to provide all the following services:

– Upgrade iPhone firmware from 1.4 to 2.0

– Unlock/jailbreak the iPhone (so we can use it with China Mobile, and run third party apps)

– Install latest version of Cydia (installer service for third party apps)

– Put on a free screen protector (and also throw in a free case)

Altogether we bought six iPhones. I was the only one that found a defect; I got a phone with a scratched screen. The vendor tried to downplay the defect at first, but gave into my demand to replace the phone even after I had paid.

Overall, a pretty good consumer experience. The iPhones you buy in China obviously don’t come with Apple support or hardware warranties, but if you find a good vendor you can go back to them for help dealing with firmware issues.

Let me know if you have any questions about the experience. I was initially somewhat wary of buying 水货, but the company subsidy was just the push I needed. After learning a lot about the iPhone in the past week, I’m quite pleased with the purchase and with the iPhone’s functionality in China, even despite a recent iTunes Stores block.

24

Aug 2008Good Job, Good Boy

ChinesePod and Shanghaiist just kicked off a collaborative podcast called Chinese Soundbites. The first one is about China’s star track athlete Liu Xiang (刘翔). On the show Jenny and Amber talk about current events in China, and give a few relevant Chinese vocabulary words.

One of the phrases in the first episode is 好样的. It’s kind of hard to translate because literally it means something like “good appearance” or “good form.” But it’s used a lot like “good job” is in English (which, conversely, cannot be directly translated as 好工作 into Chinese!).

In the podcast Jenny uses 好样的 to voice her support for Liu Xiang. It’s kind of funny, because lately my strongest association with the phrase is my wife’s use of it. We’re house-training our puppy, and every time he successfully does his business outside, my wife praises him with a “好样的!” (“good boy!“).

21

Aug 2008China Blocks the iTunes Store

From the Sydney Morning Herald:

> Access to Apple’s online iTunes Store has been blocked in China after it emerged that Olympic athletes have been downloading and possibly listening to a pro-Tibetan music album in a subtle act of protest against China’s rule over the province.

Wow, I sure have bad timing. I just bought an iPhone. I just wanted to download free apps from the iTunes store, but since Sunday evening I can’t connect at all. (I wonder how much business Apple USA gets from China, though?)

19

Aug 2008Variable Stroke Order in Chinese Characters

I started learning Japanese in 1996. When I began learning Mandarin in 1998, I already had a foundation in Chinese characters, thanks to my Japanese studies. Learning the two languages at the same time, I was frequently annoyed by little discrepancies such as 歩 and 步, 別 and 别, 氷 and 冰, etc. Those little character details caught my attention, though. I ended up writing my senior thesis on how and why the Chinese characters of the Chinese and Japanese writing systems ended up diverging.

One little detail that always nagged at me, though, was stroke order. The truth is, stroke order of Chinese characters is not consistent across Japanese and Chinese. I was reminded of this recently by Tae Kim’s blog entry entitled, What’s the stroke order of 【龜】? Who cares? He brought up the stroke order of the character 必 as an example of a “weird character.” This character just happens to be one of the ones whose correct stroke order has been ever so slightly bugging me all these years.

必 is a great example, because it shows up in plenty of relatively simple words in both languages, like 必要 (necessary) and 必须 (must) in Chinese, and 必ず (without fail) and 必要 (necessary) in Japanese.

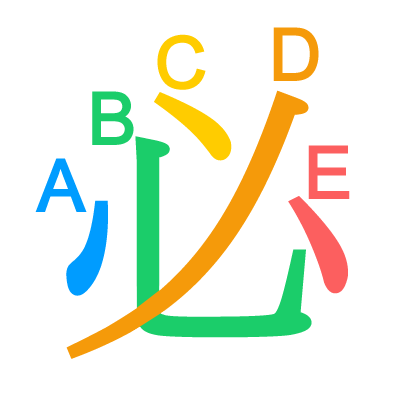

Now let’s take a look at the stroke order of this simple character. I’ll have to assign letters to each stroke so that we can keep the different stroke orders straight:

Chinese 必:

– Ocrat, MDBG, and Wenlin all say A-B-C-D-E.

– Learn to Write Characters (click on 必), maintained by Dr. Tim Xie, says A-B-C-E-D.

– A-B-C-E-D makes a lot of sense to me, because the character’s radical is 心 (but that doesn’t necessarily matter at all).

– Remember that Chinese has the added excitement of the simplified/traditional divide, as well as other regional differences in the mainland, Taiwan, and Hong Kong.

– If you have more to add to this (especially from more authoritative sources). please leave a comment!

Japanese 必:

– WWWJDIC, Kawatsu, Kodansha, and Gakken all agree on the bizarre C-D-B-A-E.

– It’s almost as is they’re writing 义 first, then adding “wings,” but no, the radical here is 心 as well. (We can see why Tae calls it weird.)

Hmmm, that’s a lot of inconsistency. Gives you more respect for the people that can create good Chinese handwriting recognition software, doesn’t it?

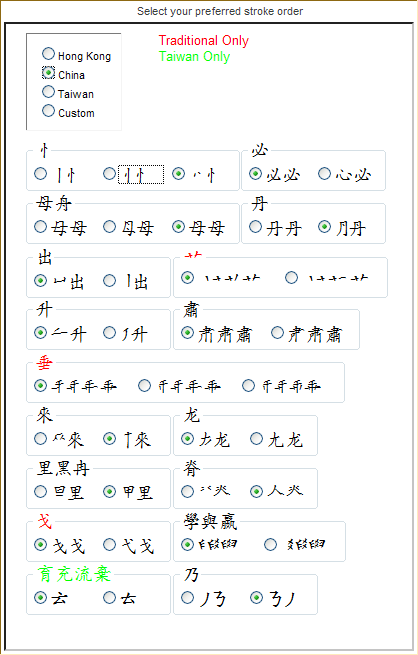

But wait! It doesn’t end there. An even simpler character — 出 — behaves inconsistently as well. I’ll spare you all the details and jump to a diagram taken from a very interesting tool I found illustrating various stroke order differences:

Note that aside from the incredibly common 出, the heart radical 忄 — a component of tons of very common characters — is also among the ambiguously stroke-ordered. Notice too that the Japanese-only variants are not included in this list.

So what’s my point? Well, it’s not any of the following:

– Chinese is really hard

– Chinese characters are really complex

– Chinese characters are hard to learn

– Chinese character stroke order is fun!

Chinese is not semi-mystical. Chinese characters were created by people a really long time ago, and thus it is an amazingly imperfect, inconsistent system. East Asian brains aren’t semi-mystical either; with all these differences going on you can bet that the Chinese and Japanese get mixed up too. In fact, armed with the chart above you’ll find it really easy to spark debates with very literate Chinese over the “correct stroke order.”

Like me, you may be bugged by these inconsistencies. You may feel compelled to seek out some underlying pattern or just memorize a big list of exceptions. Don’t do it! Be satisfied with a quick look over the chart above. Just get the non-exceptional stroke order basics down and you’ll be fine, trust me. Don’t obsess over perfect stroke order and all the exceptions, because it’s an imperfect system. The deck is stacked against you. Learn to read and use characters to communicate, and you win.

17

Aug 2008The Effect of Tonal Language Experience on the Acquisition of Mandarin Tones

This is the new, improved sequel to a comment I originally left on a Beijing Sounds entry entitled Zhonglish — Revenge of the Non-Native English Speaker.

From Chen Qinghai’s doctoral thesis (2000), Analysis of Mandarin Tonal Errors in Connected Speech by English-Speaking American Adult Learners: A Study at and Above the Word Level:

> 2.2.5.2 Tonal Language Experience

> Any language learning experience may have a positive impact on the acquisition of Mandarin tone (Bourgerie, 1995). The learning of another tone language may have greater effect on the learning of Mandarin tone (J-M. Lu, 1992). In order to find out if exposure to a tone language in childhood facilitates the learner’s performance in Mandarin tone, Sun (1997) used tone language experience as another between-subjects variable in her study. Her data show that subjects with tone language experience do have some advantage in distinguishing tone in phonologically modified contexts (p. 261); on the whole, however, their tone language background is not strongly associated with their tonal performance….

It’s hard to believe that tonal language experience doesn’t help much, but that’s what the experimental evidence suggests. I’d love to hear about more involved studies on this topic. We English speakers do like to look for excuses as to why tones are so hard for us (but this still doesn’t explain the rapid progress of Korean students!).

(The thesis quoted above was the basis for my own master’s thesis. I do intend to discuss it more, and to put some details of my own experiment online. Just need to find the time!)