20

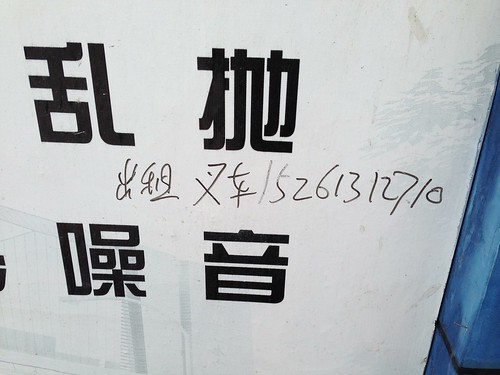

Aug 2013Text Message Fraud (a sample)

Photo by .sl. on Flickr

There’s a fair amount of text message (SMS) fraud going on in China, and if you have cell phone number here, you’re likely to receive this type of text at some point. As a foreigner, though, if you have trouble reading the text, you may get too caught up in trying to decipher what it says and forget to ask yourself, “could this be a scam?”

So here’s an example of a fraudulent text message I received just the other day:

> 我是房东,我换号码了, [This is the landlord. I’ve changed my number.]

> 你记一下,以后找我就打这个。 [Please write it down. In the future, you can reach me at this number.]

> 另外,这次租金请打我爱人卡上, [Also, this time please pay the rent to my spouse’s account.]

> 工行 621226.240200.6159780 [ICBC 621226-240200-6159780]

> 李敏,谢谢 [Li Min. Thanks!]

A few notes on what makes this text a little bit crafty:

1. The landlord’s changed his/her number. That’s why you don’t recognize the number. And you’re welcome to contact him/her at the number! Seems legit.

2. Oh, but now you have to send money. And the reason you don’t recognize the account is because it’s the landlord’s spouse’s account.

3. Here’s the kicker. The spouse’s name is Li Min (李敏). This is a deliberately gender neutral name (although it’s more likely to be a female name). The words for “landlord” (房东) and “spouse” (爱人) are also gender neutral. So whether your actual landlord is male or female, the message still works.

4. The spouse’s surname, Li (李), is not a coincidence. It’s #1 in the list of common Chinese surnames.

Don’t fall for this stuff, guys. I receive messages like this once or twice a month. They tend to follow a very similar pattern to the one above.

13

Aug 2013China, the Country of the Blind

Photo by Iris River on Flickr

I recently read H.G. Wells’ short story The Country of the Blind, and it immediately struck me how relevant this story is to western visitors of China in modern times. If you’re a China observer, and an observer of how westerners interact with China, it’s definitely worth a read.

If you’re too busy to read a short story (and it’s not overly sci-fi, for those of you not into the genre), you might check out the plot synopsis on Wikipedia.

Here’s an excerpt to give you a taste:

> “Why did you not come when I called you?” said the blind man. “Must you be led like a child? Cannot you hear the path as you walk?”

> Nunez laughed. “I can see it,” he said.

> “There is no such word as see,” said the blind man, after a pause. “Cease this folly and follow the sound of my feet.”

> Nunez followed, a little annoyed.

> “My time will come,” he said.

> “You’ll learn,” the blind man answered. “There is much to learn in the world.”

> “Has no one told you, ‘In the Country of the Blind the One-Eyed Man is King?'”

> “What is blind?” asked the blind man, carelessly, over his shoulder.

> Four days passed and the fifth found the King of the Blind still incognito, as a clumsy and useless stranger among his subjects.

> It was, he found, much more difficult to proclaim himself than he had supposed, and in the meantime, while he meditated his coup d’etat, he did what he was told and learnt the manners and customs of the Country of the Blind. He found working and going about at night a particularly irksome thing, and he decided that that should be the first thing he would change.

There really is a lot there to appreciate. Read the original.

On a related note, Kaiser Kuo has recently stated:

> On my podcast not long ago, Evan Osnos suggested that the best way to understand China today is to read Mark Twain—specifically “The Gilded Age” and “Life on the Mississippi.” Paul Mozur from the WSJ did just that and concurs. I’m now reading “The Gilded Age.” Yep.

Evan Osnos also recommends The Rise of Silas Lapham by William Dean Howells for the same reasons.

08

Aug 2013Coke’s Creative Campaign Can’t Hold Off the Tablet Wars

This big ad space in Zhongshan Park displayed massive iPad ads for the longest time, after which it was covered by Microsoft Surface ads. Just briefly, it was home to this Coke ad:

The ad reads:

> 和 型男 室友 老兄 神对手 一起分享可口可乐 (Enjoy Coca-Cola with stylish guys, roomies, old buddies, and arch-rivals.)

Coke is doing something creative with its labels this summer, using Chinese internet slang instead of the name 可口可乐 (Coca-Cola). Read more about this campaign here and here.

I noticed that as of this week, the ad space has been reclaimed by the Surface again.

06

Aug 201313 Euphemisms for Sex in Chinese

We all know that Chinese can be a little challenging to learn, and one of the reasons is cultural. Certain topics are not talked about openly by most Chinese, or at least not directly. Enter the euphemism, those delightful ways of subtly referring to a taboo topic without outright naming it (and befuddling all foreigners in the process!).

Below is a list of Chinese euphemisms (委婉语) for sex. These are all somewhat subtle, but they vary quite a bit in how modern or tactful they are. Just to be clear, if you use the words 做爱 (“make love”) or 性 (“sex, sexuality”) or 性交 (“sexual intercourse”), you’re not being subtle, and dropping those words in polite company is likely to cause some embarrassment.

OK, so here’s the list:

-

sex: This one needs no expanation, except that since it’s an English word, rather than a Chinese word, it loses a lot of its taboo flavor in Chinese (thus it’s counted as a euphemism when it’s really just a translation).

-

那个: Literally, “that.” You know… that.

Example: 他们有没有……那个过?

-

ML: Stands for “Make Love.” So once euphemized by translation, and then euphemized once again by abbreviation. I asked native speakers if there is a “ZA.” You know… for 做爱. Of course there isn’t. (And at first, before the clarification, native speakers were even confused about what in the world I could be talking about. “ZA”? Zā?) This one is often used online.

Example: ML的时候

-

happy: You may know this word as an innocuous English adjective, but in Chinese it can sometimes be a verb.

Example: 他们今天可能要happy一下。

-

睡觉: This one is pretty easy to just translate, since the euphemism is directly analogous to the English “sleep with someone.” Just remember to use 跟 in Chinese: 跟……(somebody) 睡觉.

Example: 她不会跟你睡觉。

-

爱爱: So you know how in Chinese verbs can reduplicate, like saying 看看 for “take a (quick) look”? Well, in this particular euphemism, the same little grammar trick is used for the verb 爱. Only it’s pretty unambiguous in Chinese. Cute, huh?

Example: 他们今天可能要爱爱。

-

嘿咻: This one is a little hard to explain if you’ve never heard it, but it’s the sound someone makes when engaged in some kind of hard labor. The kind where you’re breathing hard. So it’s essentially an onomatopoeia turned into a verb.

Example: 在车里“嘿咻” [source]

-

办事: This one is slightly problematic because 办事 is a little bit hard to nail down even in the non-euphemistic sense. It’s kind of like “get some work done,” or “handle some (official) business.” Perhaps the most (unintentionally) appropriate translation in this particular case is “handle affairs.”

Example: 男人、女人“办事”时喜欢开灯和不开灯的理由 [source]

-

发生关系: I love how spontaneous this one sounds. 发生 means “happen” or “occur,” and 关系 means “relations” or “relationship.” So sometimes “relationships happen.” The interesting thing is that this one is actually fairly formal; it can be used as an almost classy euphemism without the need for any additional chuckling or winking.

Example: 为什么男女发生关系后一切都变了? [source]

-

床上运动: “Exercise in bed.” Need I say more? Often used as a noun phrase.

Example: 床上运动一周几次才正常? [source]

-

上床: “Get in bed.” Again, this one isn’t too hard for an English speaker to decode. As with 睡觉, the pattern is 跟……(somebody) 上床.

Example: 她不会跟你上床。

-

房事: Literally, “room affair.” I’ve actually never heard this one myself, but I’m assured that it is definitely used, and sometimes even by doctors. It can also be used as a verb.

Example: 怀孕后多久不能房事,为什么? [source]

-

云雨: Ah, “clouds and rain.” (Yeah, you know what I’m talking about!) This one is definitely the most poetic of the bunch. To me, it smacks of “the birds and the bees,” only classier.

I’ve got no examples for this one. My searches turn up a whole bunch of Chinese people asking how 云雨 came to mean 做爱 in ancient Chinese. It’s not normally used in spoken Chinese.

So that’s enough euphemisms for now! Next euphemism post: Chinese euphemisms for death.

01

Aug 2013Thoughts on Summer Blockbuster “Pacific Rim” in China

Last night I went to see the movie Pacific Rim at Shanghai’s newest, biggest mall, Global Harbor. My hopes were not super high, but I ended up really enjoying the film. I had totally forgotten that it was directed by Guillermo del Toro; I think it was suddenly seeing Ron Perlman’s face in the movie amongst all the other relatively unknown actors that reminded me. Anyway, very fun movie.

A few things struck me about seeing the film in China:

1. The Chinese mech dies first. This is kind of a shame, not because they’re Chinese, but because their badass red, four-armed robot with buzz-saws for hands looked awesome, and I would have liked to watch it do a little more damage in battle. This didn’t really seem to bother the audience, though; the Chinese mech pilots weren’t even really characters in the movie… easy come, easy go.

2. The human characters in the movie use the Japanese term kaiju (怪獣) for the giant monsters they’re fighting. This was kind of interesting. The (simplified) Chinese is 怪兽. (Another common word for “monster” in Chinese is 怪物.)

3. The Hong Kong Chinese are experts at dicing up the kaiju (giant monster) corpses and selling the parts on the black market (as “medicine”?). There is discussion of the going rates for ground kaiju bones and various kaiju organs. This struck me as both a funny stereotype as well as somewhat insightful.

What do you think? Racist? Or would the biological matter derived from monsters from another dimension totally be worked into the black market, extreme fringes of TCM relatively quickly?

30

Jul 2013Tracking the Evolution of the Slang Word “Diaosi”

The Chinese slang word 屌丝 (meaning approximately “loser”) has become pretty popular in recent years, thanks to the internet. Of course it’s got its own Baidu Baiku entry (in Chinese), and you can find it in the ChinaSmack glossary (in English) too.

But there are a few weird things about this term. First, sources don’t always agree whether 屌丝 is pronounced “diǎosī” (3-1) or “diàosī” (4-1). [My personal sources usually assure me it’s 3-1.] Second, isn’t 屌 a vulgar slang term for “penis”?

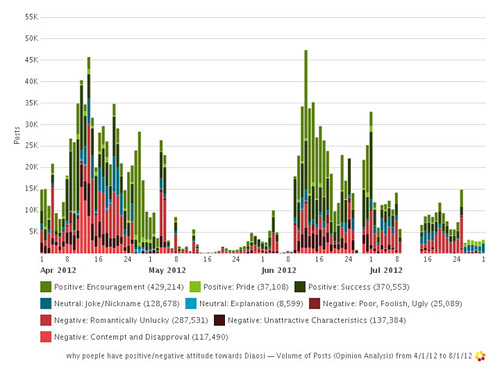

Rather than delving into these issues myself, I’d like to direct you to an article on a new blog called Civil China which, as one of its first articles, takes a look at how the term has surged in popularity in recent years, and even how connotations shifted from mostly negative to not-so-negative. The article is Diaosi: Evolution of a Chinese Meme.

The post includes some very interesting textual analysis of the use of the term 屌丝 on Weibo over the past year and a half. (Complete with fancy data visualizations!)

For those of you actually trying to learn vocabulary (and possibly too lazy to read the whole thing), don’t miss this conclusion about the meaning of the word 屌丝:

> Although “diaosi” is often translated as “loser” in English, our analysis points to a distinction between a Chinese “diaosi” and a “loser”: losers are responsible for their own lack of success, while diaosi are made by larger social conditions. No wonder then, that “loser” remains an indisputably negative term, personal in its injury, while “diaosi” is a true meme: dynamic, complex, and current, cultural rather than personal.

25

Jul 2013Help with the Chinese Usage Dictionary

Yale University has a great Chinese Usage Dictionary with 85 entries. Only problem is that it uses the deprecated HTML practice of frames, and the links in the left sidebar are not right. You actually can get to the articles by hovering over the links, noting the HTML file it points to, and then editing the URL in your browser, but that’s a bit tedious.

To make access easier, AllSet Learning has added an index page for Yale’s Chinese Usage Dictionary, and at the same time, added a few relevant Chinese Grammar Wiki links as well. Check it out!

The Chinese Usage Dictionary isn’t a full dictionary in the sense of Pleco or MDBG, and it doesn’t stick strictly to vocabulary or grammar, alternating between the two. But if you like comparisons of similar words with examples of correct and incorrect usage, or want some exercises, then definitely give it a look.

23

Jul 2013Door Door

Here’s a Chinese door that not-so-subtly reminds you it’s a door:

“Door” in Chinese is written 門 in traditional Chinese, and 门 in simplified. Obviously, the character above is traditional.

Unfortunately, it’s not a door to a door shop or anything quite so fitting.

16

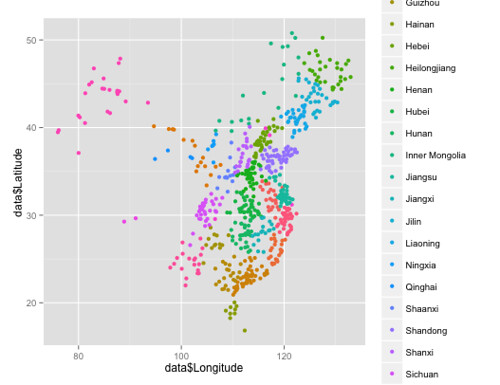

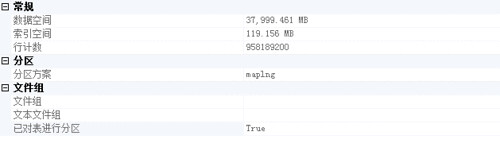

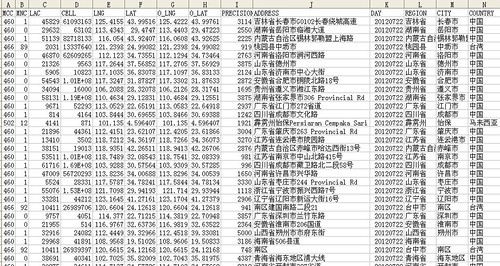

Jul 2013A More Complete iOS Solution to the China GPS Offset Problem

This is a guest post by a friend, [unnamed for now]. It goes quite in-depth into China’s GPS issue, which I’ve complained about here before. The hope is that, armed with the following information, non-Chinese developers will be able to get around the issue more quickly and more effectively. Note that while the information below was applied to iOS app development, it isn’t strictly iOS-specific.

Description of the Problem

One problem that often comes up when people stay in China for an extended period of time is that they find their GPS devices don’t work. Sure your iPhone or Android phone will report your own location just fine, but try using a route tracking feature when you’re jogging or if you use an app showing other people’s GPS locations like Find My Friends, you’ll likely see they’re standing in a river or some place 500 meters away even if they’re standing right next to you.

This is the mysterious China GPS offset problem. This has been covered in a few posts [in Chinese] here, here, and here. Basically the Chinese government strictly controls mapping data within China. It’s illegal to map or create GPS traces within China without authorization. There have been stories of a few foreigners who created hiking trails near sensitive buildings w/ GPS devices being arrested due to relevant local laws.

For popular map apps such as Google Maps or Apple Maps on iOS, the user’s own location will be correct. This is because licensed companies that register with the government will be given the corrected algorithm to adjust the user’s position. Google Maps, Bing and others allow you to search for a location based on the GPS coordinates, but no local Chinese map providers such as Baidu Maps allow you to.

If you had taken a photo near the Forbidden City, load the photo into iPhoto or Picasa and look at where it is on the map you’ll see the location is just a bit off, 300-500 meters and typically about a block or two away. Not far enough to be extremely inaccurate but incorrect enough to annoy and not place you in the proper position.

Two GPS standards

The most common GPS standard used internationally is based on a coordinate system called WGS-84. The globe is an imperfect sphere and any mapping from 3D to 2D introduces some compromises. People who get really into it will note that as you get further away from the equator, the way GPS coordinates for latitude and longitude change aren’t the same even if you’re traveling the same distance. However this is the GPS we’ve come to know and is used globally.

China uses a standard called GCJ-02 which is based off an older Soviet system of coordinates introduced in the 1940’s. It’s converting from WGS-84 to GCJ-02 that we’d like to accomplish. Chinese programmers refer to this coordinate system as the 火星坐标系统 or “Mars coordinate system” (as in you’re mapping from Earth with WGS-84 to Mars in GCJ-02).

Preliminary tries to correct the problem

Static offset

The first tries in the English-language world to correct for this China offset problem noticed that in local areas like within the city of Shanghai or Beijing, the difference was relatively fixed. That is, if you just subtract a few degrees from the latitude and add a few for longitude, you can correct the position. They quickly realized that the translation was non-linear, though, changing from city to city.

Collecting data points

Approaching this problem myself, I found out that as long as I was within China’s IP range, I would see the iOS simulator report my simulated location correctly, but if I dropped a pin on the same GPS coordinates it would be off. I created a simple app that let you drag the pin back to your real location and after scraping Wikipedia’s list of cities in China, had 657 data points.

Using Excel’s LINEST function you can split the data up into groups and actually get a pretty decent correction that works across the whole country although it will still be off by a few meters. Enough to put you across the street from where you really were or down a few stores.

It turns out if you search in Chinese, several people sell massive data sets of tens of thousands of points within China with their corresponding offset. Apparently people have run into this need before. On Taobao you can find sets from 400 RMB to 900 RMB.

Hints at already solved code

A few English language posts stated that Chinese Android coders had already released the proper algorithm in open source. After several searches in Chinese, finding relevant posts was easy. But the actual ones that solve the problem took more hunting until I found the personal website of Rover Tang and a post on a popular tech site called XCoder.cn.

Solution found and explained

Keeping it brief, the originally released code was a C file that took into account all sorts of height, GPS time and date etc. even though they were unused. This could be found several places online. A refactored and cleaner version of the code is available in C# on EvilTransform.cs.

It’s basically a complicated transform using equations describing an ellipsoid (what the Earth is) from one system of coordinates to another. Once you throw in GPS in WGS-84 you get the same ones back in GCJ-02.

You’ll note that the code interprets that anything within China needs this conversion, anything outside of China, doesn’t. And that China is defined as anything between Latitude 0.83 to 56 and Longitude 72 to 138. I think there’s a few countries caught in that rectangle that might object.

So what now?

So now any web or mobile app developers who need to record GPS paths, post GPS locations, or anything else on top of a map can now have the proper locations. It was a huge relief to me to finally find a solution that works anywhere in China so we can all go back to creating apps that work.

References

- Overall summary of the situation

- Baidu Baike definition of the Mars Coordinate system

- Explanation of the algorithm with links

- EvilTransform.cs – The most legible version of the code

- iOS code that does Baidu and GCJ-02 to WGS-84

- Links to Taobao offers for data sets: 1, 2, 3

Dec. 23, 2014 Update:

A developer recently found this post vey useful in solving his own China location app problems, but needed some additional information to properly implement the above advice. I’m sharing that extra information below in the hope that it’s useful to more developers:

Apple returns their coordinates in the WGS format and offsets the map when rendering (I thought the coordinates themselves were offset, not the rendered map).

Not mentioned but deduced from the above was that Google does it the other way around… if I’m not mistaken, Google returns the GCJ coordinates for a China location (even if you are not in China)… This explains why Apple’s coordinates are off when input into Google until they are converted into GCJ.

MapKit only offsets the map from devices within China.

Because we were testing on devices in and out of China we weren’t sure where the root problem was; we had tried the conversion, but then tested the results with MapKit on a device that was outside of China.

11

Jul 2013The Wheely Spotted in Shanghai

I saw this guy on the street the other day in Shanghai’s Hongkou District:

A little research seems to indicate that this is the Wheely 500W by BeInMove. €899 is over 7000 RMB. Not only is that expensive, but I’ve never seen this kind of thing for sale here. I wonder where this guy got it…

Update: it seems to be selling for 2999 RMB on Taobao. (Thanks, Brad!)

09

Jul 2013Meaningful Chinese Transliterations (for fun!)

One of the big headaches about learning Chinese is the relative dearth of cognates and loanwords. None of that “car” is “carro” stuff you get when you start learning Spanish. In fact, when you do learn words that were transliterated into English from Chinese (like 麦克风 for “microphone”), the result is often bizarre and a lot harder to learn than if it had been “more Chinese” (keep in mind that you also have to learn all the tones of the word transliterated into Chinese). Kind of a downer.

It seems to me that the Chinese aren’t too crazy about these transliterations either. When they can, they’ll do things like use the Chinese word 苹果 (“apple”) for the American company “Apple” rather than resorting to transliteration. But for foreigners’ names, foreign country names, foreign company names, foreign brand names, and foreign product names, you do get stuck with an awful lot of transliterations into Chinese.

Recently I came across this list of English words (probably taken from a list of vocabulary words for some horrible standardized test) that have been transliterated into Chinese in a humorous way. That is to say, the Chinese characters chosen, rather than being random or “standard transliteration characters,” were chosen for their meanings. I’ve added pinyin tooltips to the transliterations, and also English translations of the transliterations.

– pregnant (怀孕): 扑来个男的 (“throw a man on me”)

– ambulance (救护车): 俺不能死 (“I can’t die”)

– ponderous (肥胖的): 胖得要死 (“ridiculously fat”)

– pest (害虫): 拍死它 (“squash it”)

– ambition (雄心): 俺必胜 (“I must win”)

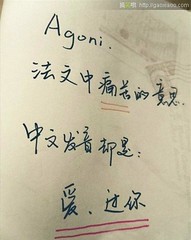

– agony (痛苦): 爱过你 (“having loved you”)

– hermit (隐士): 何处觅他 (“wherever can I seek him?”)

– strong (强壮): 死壮 (“damn strapping”)

– abyss (深渊): 额必死 (“I must die”)

– admire (羡慕): 额的妈呀 (“mama mia”)

– flee (逃跑): 飞离 (“fly away by plane”)

– gauche (粗鲁的): 狗屎 (“dog crap”)

– morbid (病态): 毛病 (“mental issues”)

– putrid (腐烂): 飘臭 (“wafting stench”)

– obtuse (愚笨): 我不吐死 (“I’m not going to puke to death”)

– lynch (私刑处死): 凌迟 (“kill by dismemberment”)

– tantrum (脾气发作): 太蠢 (“too stupid”)

– bachelor (学士/单身汉): 白痴了 (“turned dumb”)

– temper (脾气): 太泼 (“too unreasonable”)

– addict (上瘾): 爱得嗑它 (“love to the point of cracking it in your teeth”)

– economy (经济): 依靠农民 (“rely on the peasants”)

– ail (疼痛): 哎哟 (“Owww”)

– coffin (棺材): 靠坟 (“leaning on the grave”)

– appall (惊骇): 我跑 (“I’m gonna run”)

05

Jul 2013Chinese Baijiu Toasts as an RTS Video Game

The “Chinese Banquet Baijiu Toast” video game needs to be made. (Indie game developers, this idea is free. Hurry up and go start a Kickstarter campaign!)

I was having dinner last week with former AllSet intern Parry and current AllSet intern Ben, and we started talking about baijiu (白酒) drinking strategies. I told them about my friend Derek who kind of made himself into an authority on baijiu by drinking way more of the foul liquid than most white people ever have. And then we started talking about baijiu toasts at Chinese dinners. I told them about my experience in Baoding last CNY, and how our hosts had brought “baijiu assassins” to bring down my father-in-law, who’s kind of legendary in the bajiu-drinking department. And I told them about some of the different strategies that are used in big banquet situations where the baijiu flows freely.

What are these strategies, you ask? I’m not talking about cheap “drink water instead of baijiu” tricks, I’m talking about respectable above-board strategies for these drinking events. Some basic ones:

1. Ganging Up: Individuals go toast one particular person, one by one, in rapid succession. That way each “attacker” only has one shot of baijiu, but the “victim” has many, with no time to recover.

2. Table Takedown: Similar to “ganging up,” but you send one person from your table to toast an entire table (everyone at that table must do a shot). When that person from your table returns, you send another person from your table to toast the whole table again. Repeat ad nauseam (and I do mean nauseam!).

3. Empty Table: If things get hot and heavy and there are enough tables at the banquet, it might be wise for everyone at the table to fan out and do multiple table takedowns (or ganging up) at the same time. That way there’s no one left at your table to get taken down! This is also a good time to go to the bathroom, but beware: if you seem to just be running from your drinking duties, you’re just asking to get ganged up on.

Now rarely is there really this much strategizing going on, I think (although there certainly was that dark night in Baoding!). But it makes me think that this could make a cool strategy game. It all reminds me of an RTS (real-time strategy) game like Starcraft.

Could some indie game developer make the Starcraft of Chinese Baijiu Toasts? That would be cool… As long as I don’t really have to drink any baijiu to play!

Thanks to Mei for doing the PSing!

02

Jul 2013The Foreign Feel of a Chinese Transliteration

Foreign words, like “Minnesota” or “Kobe Bryant” or “Carrefour” often get “translated” into Chinese in a way that uses the original sounds of the words and tries to represent those in Chinese (thus, using Chinese characters). This process is called transliteration, or sometimes transcription (音译, which breaks down character by character into “sound translation” in Chinese). Thus, the three examples above become “Mingnisuda” (明尼苏达), “Kebi Bulai’ente” (科比·布莱恩特), and “Jialefu” (家乐福) in Chinese.

These foreign names can be quite a pain for learners to remember, because the pronunciation is “off,” and they’re often quite long, plus the worst part: you have to remember all the tones for those “nonsense characters!”

But are they really nonsense characters? That depends. A carefully transliterated name will make some sort of sense in Chinese. This is almost always done with company and brand names, and is the case with Carrefour (家乐福) above; the three characters chosen mean “home,” “joy,” and “happiness,” respectively. For place names, though, the characters are a bit less lovingly selected. So Minnesota (明尼苏达) got: “bright,” “Buddhist nun,” “Suzhou,” “arrive.” Pretty random. Same goes for “Kobe Bryant” (科比·布莱恩特) in Chinese.

So a typical learner of Chinese wants to know: what’s my name in Chinese? And that’s where the tumble down the foreign name transliteration rabbit hole begins. You see, most English names already have standard translations in Chinese. So “John” is 约翰, “Mary” is 玛丽, “Richard” is 理查德, etc. Clearly, these are all transliterations; the sounds are approximated in Chinese, but not the meanings.

From the moment I first heard “约翰” (“John” in Chinese), I hated it. It didn’t sound like “John” at all! There wasn’t even a “zh” or a “j” sound in the whole name. (It does sound quite similar to “Johann,” though; I think I had early European missionaries to thank for the “standard” transliteration of my name.)

After examining the characters, there were two main things I didn’t like about 约翰:

1. The characters 约翰 didn’t make much sense (OK, they make a little sense, from a “Gospel of John” missionary perspective)

2. “Yuēhàn” just sounded weird to me, and unlike most Chinese names

These two features define most foreign names transliterated into Chinese. In fact, oftentimes the characters really are nonsensical; they’re chosen systematically from a fixed list of characters used in transliterations. This list even has its own Wikipedia page: Transcription into Chinese characters.

Looking over the list, I can’t help but feel that certain specific characters are more “foreign” (used especially often in foreigners’ names, and not so often in Chinese names), while others are more “Chinese” (equally likely to appear in Chinese names). For example, 文 and 平 are both common in Chinese names. 托 and 斯… not quite so much.

Thus, over time, as you hear more and more combinations of these “transliteration characters” (杰克, 汉克, 路易, etc.), you start to get a feel for when a “Chinese name” sounds foreign, especially compared to the growing list of authentic Chinese people’s names you’re compiling in your memory. In fact, a computer program could actually run through big long lists of transliterated foreign names and original Chinese names, and by comparing the character distributions in the two lists, assign “Chineseness” and “foreignness” values to each character, allowing for fairly accurate prediction of what “Chinese” names would sound the most foreign. You could probably increase accuracy by taking note of the position of the characters in a word, and certain repeated character sequences (like 斯坦).

But this is what your brain does unconsciously as you learn more and more names. This is how we develop a sense for when a Chinese name feels foreign.

The ironic part of all this for me personally is that after rejecting 约翰 as my Chinese name, I later settled on 潘吉. Both of those characters are in thetranscription table! (Ah, but 潘吉 is actually much more Chinese, even if a bit boring. So 潘吉 is my official Chinese name, although these days I usually just go by John.)

28

Jun 2013Shanghai had no Grid Plan

I saw this Speed Levitch video in which he rails against the grid plan of New York City, and I couldn’t help but think of my adopted home of Shanghai. Here’s a quote from the video below:

> “Let’s just blow up the grid plan, and rewrite the streets to be much more a self-portraiture of our personal struggles, rather than some real estate broker’s wet dream from 1807. We’re forced to walk in these right angles… I mean, doesn’t she find this infuriating?”

23

Jun 2013Strong is good

Here’s another one for the Chinese pun file:

So the name of the sugar is 浓好, a play on the expression 侬好, the Shanghainese version of 你好, or “hello” in Mandarin. 浓好 (the name of the sugar) literally means “strong is good,” where “strong” is the “strong coffee” kind of “strong.”

The character-savvy among you (who understand the necessity of radicals) will also notice that 侬 and 浓 share the phonetic element 农, and that in this case the person radical in 侬 and the water radical in 浓 carry meaning.

On the sugar packet we can also see it is from the “Hello Milk Tea Series.” It does make me wonder what else is in the series…

19

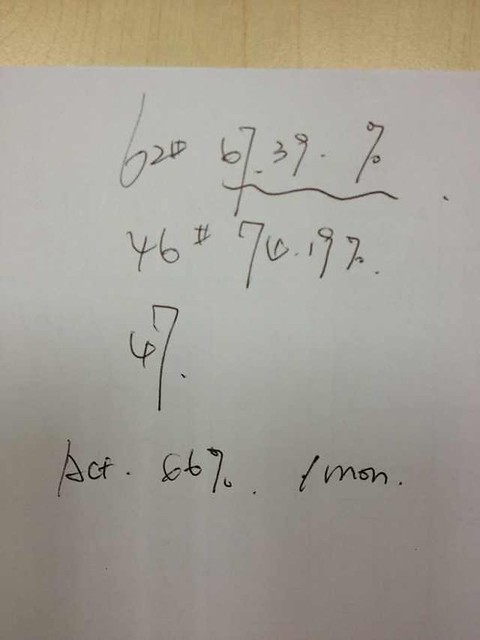

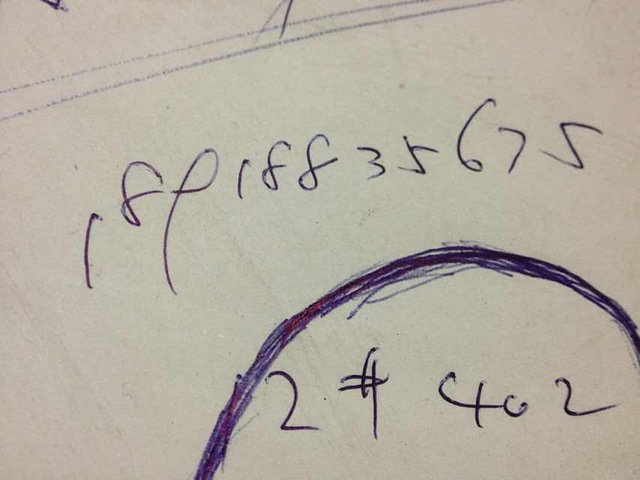

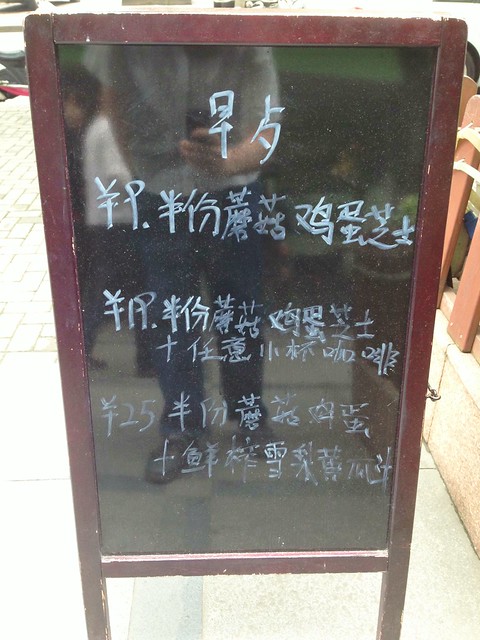

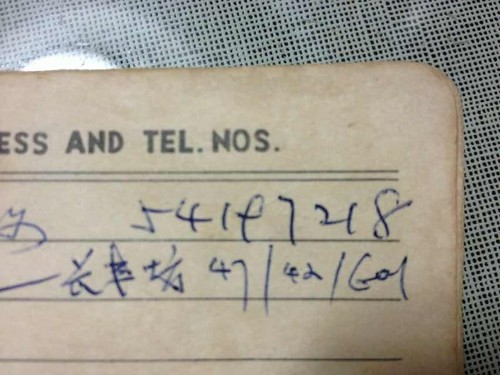

Jun 2013Handwritten Chinese Numbers: Alternative Arabic Numerals

I mentioned before in my post “Chinese Numbers: Where 4 Meets 6” that I’d have a longer post on this topic. This is it (although not quite as long as I was hoping). Again, I don’t mean the Chinese character numbers (一、二、三、四、etc.); I’m talking about the numbers we call Arabic numerals. In China, they can occasionally be written pretty differently from what foreigners are used to, and present serious potential for confusion and misunderstandings.

4 and 6

This is the issue I mentioned before, and illustrated with this image:

I actually had a hard time finding really good examples of this “in the wild,” but here’s a fairly representative example:

Here are some more “normal” 4s:

9

This one is the easiest to document, and by far the least recognizable to Westerners, in my opinion. How do you even describe it? Kind of like a cross between a “P” and a “q”? Spot the 9s!

This last one is interesting:

You’ll notice the same hand that wrote the wacky 9 also wrote 早餐 as the non-standard 早歺 (that’s a second round simplification character).

5

Sometimes it looks like a backwards Z, and other times it looks like a weird curvy thing with a line through it. In an un-5-like way!

One more…

As a bonus, here’s an 8 that looks like a 6:

Sooo…?

Consider this post a little heads up. If you’re suddenly in a situation in China where you have to be reading numbers, running into these forms can be a little bewildering.

Also, I’ve been trying to collect representative examples for months, and this is all I’ve come up with. (And three of them came from ChinesePod co-host Dilu. Yes, the food-related ones were all me.) If anyone could share additional examples that I’m allowed to post, please email them to me, or link to them in the comments, and I’ll add them here as an update.

Other comments are, of course, also welcome!

11

Jun 2013Privacy: a great conversation topic

This whole PRISM debacle has freaked out and enraged a good section of the American population, and with good reason. But if you try talking about the issue with a Chinese citizen, some very interesting themes may emerge.

Here’s an imagined dialog to illustrate the point:

> American: Did you hear about this whole PRISM thing going on in the U.S.?

> Chinese: No, what is it?

> American: The U.S. government seems to have made a deal with a bunch of major internet companies to get all kinds of supposedly “private” information on all kinds of people.

> Chinese: And?

> American: Well, it was kept secret until recently, when the truth was revealed.

> Chinese: But this was actually surprising to the American people?

> American: Well yeah! We have a right to privacy.

> Chinese: Sounds like Americans and Chinese have pretty similar rights to privacy.

> American: Whoa, whoa… not the same thing! We have rule of law, we have democratically elected leaders, and we can actually speak out against this thing and effect change!

> Chinese: Yeah, good luck with that.

So the Chinese person above was depicted as overly cynical for dramatic effect, but seriously, you should have a conversation with your Chinese friends about the topic of privacy (隐私). It’s not just a political issue; it’s also a cultural issue, and it’s really interesting to hear the views of young Chinese people on privacy. I talked with some friends about some of the issues in the article Why Privacy Matters Even if You Have ‘Nothing to Hide’, and it provided a great starting point for this complex topic.

03

Jun 2013Valuing Vocabulary

My daughter is now one and a half years old, and while she can’t say much yet, I know that little brain of hers is hard at work acquiring language.

One thing that’s become really obvious lately is how much she values the words she already knows. Every morning, as soon as she can, it’s all “Mommy! Mommy, Mommy…” and “Daddy! Daddy, Daddy….” It’s not just that she’s happy to see us in the morning; I’ve come to realize that she’s still slightly uncertain of her mastery of her earliest words (she still occasionally fumbles with the words she knows). She wants to use these words as much as possible because she worked hard to learn them, and doesn’t want to forget them.

And I couldn’t help but wonder: how much do we learners really value the words we learn? I mean, we value them enough to “learn” them in the first place, but do we value them enough to put in the ongoing effort to keep them? When we learn words that we know are useful, do we make damn sure that we use them right away, repeatedly, so that we never let them go?

Granted, not every vocabulary word is going to be as crucial to us as the words “Mommy” and “Daddy” are to a baby. But still, with applying a fraction of that earnestness would go a long way. I’m finding myself grateful for this new daily reminder I have.

27

May 2013Hopelessly Doomed Scooter Ride in China

This video is too amusing to just let it go by… This guy on his scooter is so comically bad that it almost feels engineered. Like it’s meant to be some kind of allegory or something. Anyway:

Here’s the 4.5 MB animated GIF version (blown up 2X):

[Sorry, had to remove the GIF… it was getting too much traffic, and it’s a fairly large file!]This GIF had the title “humanity is powerless to stop him from riding his scooter” (人类已经无法阻止他骑摩托车了) on the Chinese site it was posted to.

And a great comment from YouTube:

> my computer must be muted… i don’t hear any benny hill music

On the other hand, if you’ve ever been afraid to ride a scooter on the streets of China, this video might actually give you some hope…

23

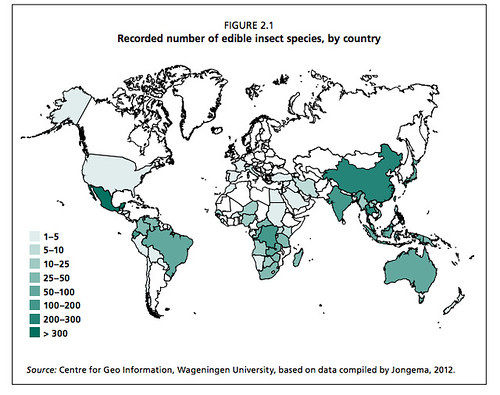

May 2013Eating Insects and Animals in China

I recently read the article Five reasons we should all be eating insects.

(I think I would totally eat insects if any of them were as delicious as shrimp, the grasshoppers of the ocean. Alas, I’ve tried eating various types of bugs in China, and they’re just not that tasty. Or… maybe they take quite a bit of getting used to?)

Anyway, reading the article, two China-related thoughts jumped out at me:

1. China should be eating more insects

With this massive population and the multitude of food safety issues, it makes sense, right? And look at the abundance of edible insects in China (especially compared to the U.S.)!

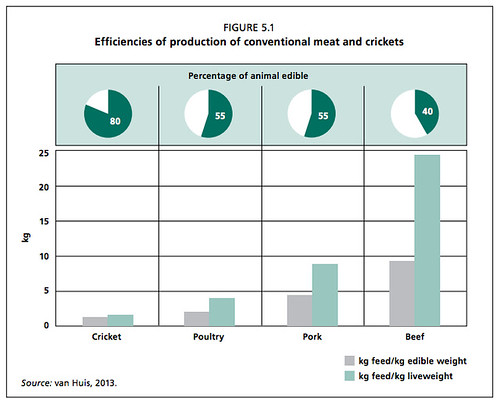

2. What would China’s “percentage of animal edible” figures be?

I know that the U.S. and China have very different thoughts on “percentage of animal edible” for all kinds of animals, including poultry, pork, beef, and lamb. So which numbers are these, and what are the differences between the numbers of the U.S. and China?

The Chinese have never been squeamish eaters, and as long as the cooking methods themselves were Chinese, I can imagine a China where people eat insects in larger quantities.