01

Apr 2020Challenges to Character Understanding

I recently read this post on Hacking Chinese: 5 levels of understanding Chinese characters: Superficial forms to deep structure and it really struck a chord with me. It reminds me a little of my own “5 Stages To Learning Chinese,” but it highlights some really great issues related to character learning which I’d like to dig into.

I’ll first do a quick summary of the author Olle’s 5 stages, but in my own words:

- Chineseasy Mode: Fully arbitrary character-image associations

- Lazy Heisig Mode: Systematic arbitrary character-image associations

- Diligent Heisig Mode: Systematic character-image associations, with substitutions

- OCD Heisig Mode: Systematic complete character-image associations

- Scholar Mode: Straight-up character origin research

Apologies to Olle, in that I may be misrepresenting his 5 stages a little bit in order to make a few points, but I believe that our groupings are mostly similar, and in any case, I am piggybacking on his article.

Chineasy Mode

This is not a compliment. I’m not a fan of Shao Lan’s Chineasy, at least not for any serious student of Chinese. Chineasy is fine as a fun “Chinese Characters Lite” if you have no intention of becoming literate in Chinese. (See also Dr. Victor Mair’s thoughts on it.)

The problem with it is that it’s not a system. It’s just Chinese character dress-up. You can’t memorize thousands of Chinese characters without a system. It’s how the Chinese themselves do it, and it’s how learners need to do it.

The question, then, becomes: how complicated of a system does this need to be?

Lazy Heisig Mode

I’ve written a little bit before about James Heisig and his books Remembering the Kanji (for Chinese characters in Japanese) and Remembering the Hanzi (for Chinese characters in Chinese).

Heisig’s work was an absolute breakthrough in the 1980’s. It was a breath of fresh air at a time when no one seemed to understand that practical language learning and scholarly language study of Asian languages did not have to be the same thing.

Heisig had the gall to “blasphemously” suggest that some systematically recurring character components could be assigned arbitrary meanings that the learner made up himself in order to concoct little mnemonic stories help him remember the correct meanings of the full characters.

If the “arbitrary” part is applied in moderation, this is definitely an improvement over the previous level, becomes you’re bringing a system into it. You’re recognizing that many character components are clear and easy to remember, plus they repeat a lot across different characters, and there’s a good reason for it. For the ones that aren’t clear or easy to be remember, you have a plan B. It’s a pragmatic system.

The problem here is that not every component has an obvious meaning, and if you start assigning many of your own un-scholarly meanings when you only know 50 characters, you’re not going to fully realize until you get to 500 characters that you really shouldn’t have chosen that meaning for that particular character component. But to change it now means changing a bunch of stories you had memorized. Yeah… it can be messy.

Diligent Heisig Mode

So if you were “lazy” before because you didn’t care what most components actually mean (historically), you’re “diligent” now in that you at least try to match the character components you are learning systematically to some kind of historical meaning.

You’re also actually paying attention to the difference between semantic (meaning) components and phonetic (sound) components. The extra time and effort spent here will really pay off when you make it to the advanced levels of your Chinese studies.

Keep in mind, however, that sometimes the “historically accurate” character breakdowns are simply not helpful or not practical (see “Scholar-Only Examples” below). In cases like these, even the “diligent” student may need to make a call in favor of his own sanity. He may need to “make something up” from time to time, but he tries not to. (In any case, the characters he punts on are likely the same ones literate native speakers have no clue about either.)

OCD Heisig Mode

But what if having a rough idea of semantic and phonetic component roles is not enough? What if you have to know the role of every character component for every character?

Well, I’d say that you may be a bit OCD… Or maybe that’s just your personal interest.

In either case, you’re probably spending far more time on your system than you need to. (What’s more important: your system, or reading Chinese?)

I won’t say too much about this.

Scholar Mode

Some learners really want to know the ins and outs of every character. And that’s cool. Clearly they have an interest that goes beyond the average learner’s.

But is this how far a learner needs to go? No. Recommending other learners go this route reminds me of a conversation I had with my 9th grade algebra teacher:

Me: Can we use a sheet of formulas for the test?

Teacher: No.

Me: *crestfallen* So we have to memorize them all.

Teacher: Well, I didn’t say that…

Me: *hope in my eyes* What do you mean?

Teacher: Well, if you understand the principles behind the formulas, you don’t need to memorize them when you can simply derive them yourself whenever you forget them…

Me: *hopes shattered*

These two people are not living in the same world.

Assessing the 5

Like Olle, I’d put myself in group 3, and it’s what I recommend that most clients do. As an elementary learner I was once in “Lazy Heisig Mode,” but I eventually realized my “system” was a bit of a mess, and I did the extra work to get to “Diligent Heisig Mode.” It’s a good place to be.

I’d say the 5 levels apply to most people like this:

- Chineasy Mode: Tourists only! You’re not a serious learner, and that’s OK.

- Lazy Heisig Mode: You’re not fully committed, and that’s OK too. If you decide to “go all the way” with Chinese, you can still upgrade later.

- Diligent Heisig Mode: You’re committed, and you don’t want to waste time forgetting and relearning. You’re building a strong foundation for the long road ahead.

- OCD Heisig Mode: I’m not sure you really exist? But anyway, if you do… you do you.

- Scholar Mode: The world needs scholars! Thank you for your hard work. (Just remember that not everyone aspires to be at your level.)

Scholar-Only Examples

You may not understand why it’s difficult and messy to learn the correct origins of all the characters you learn. I felt the same way once. I was all, “hey, I like language. I can handle it.”

OK, fair enough. I have some examples for you. No, you will not see the characters 山 or 月 or 好 or 明 or even 上 and 下. Those are the ones used to prove the opposing argument. Let’s look at a very simple beginner-level sentence.

你是我的朋友。 (Nǐ shì wǒ de péngyou.)

This is a first-semester Chinese sentence which means “You are my friend.” Easy vocabulary, easy grammar. Now let’s look at the characters.

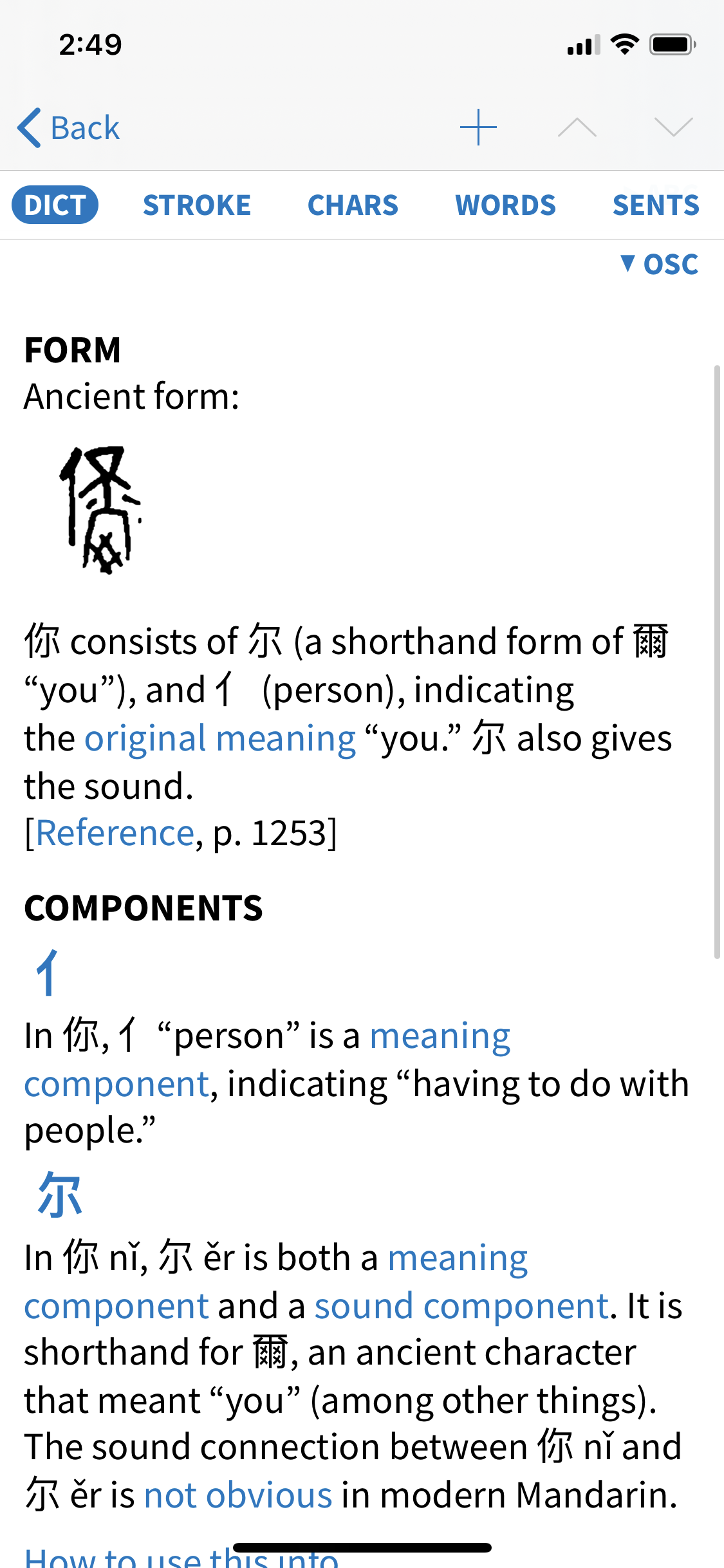

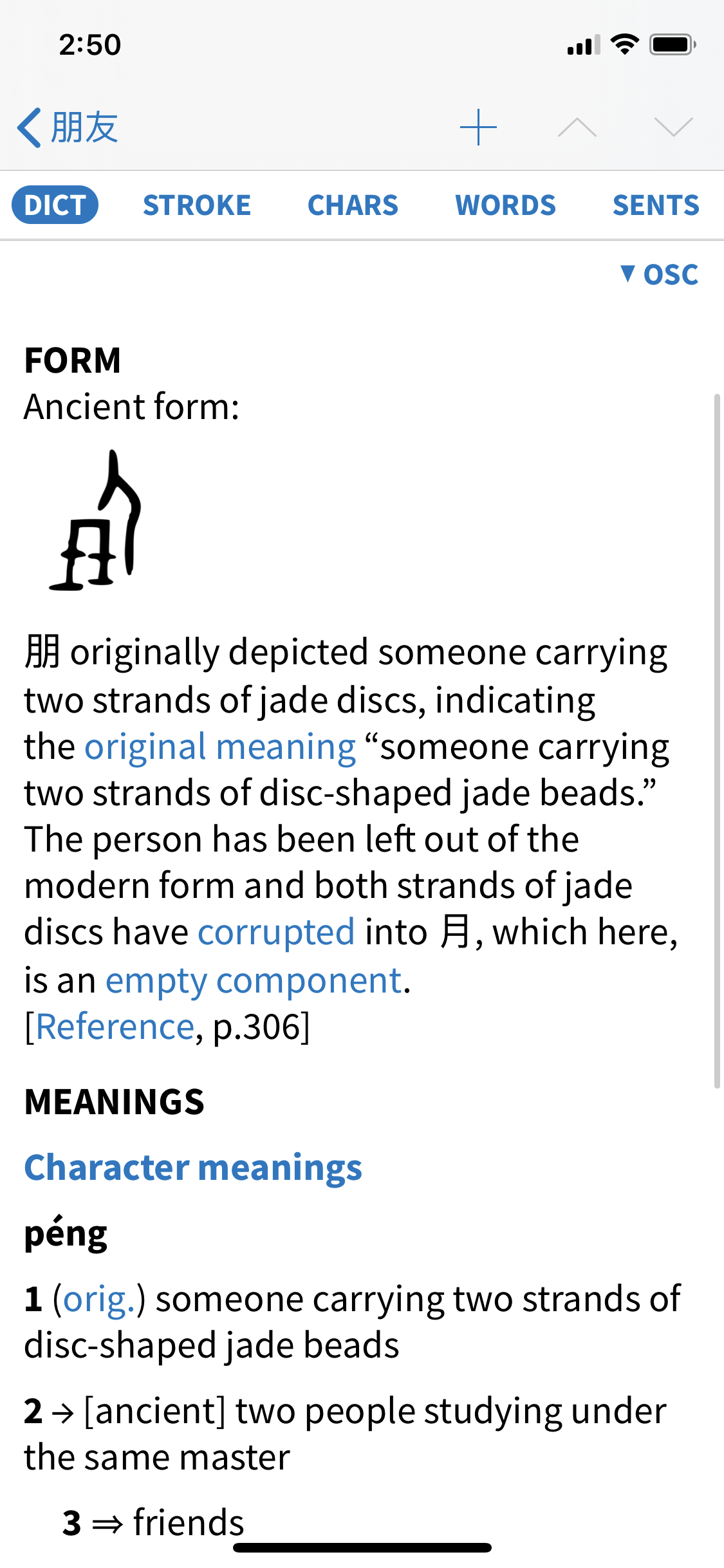

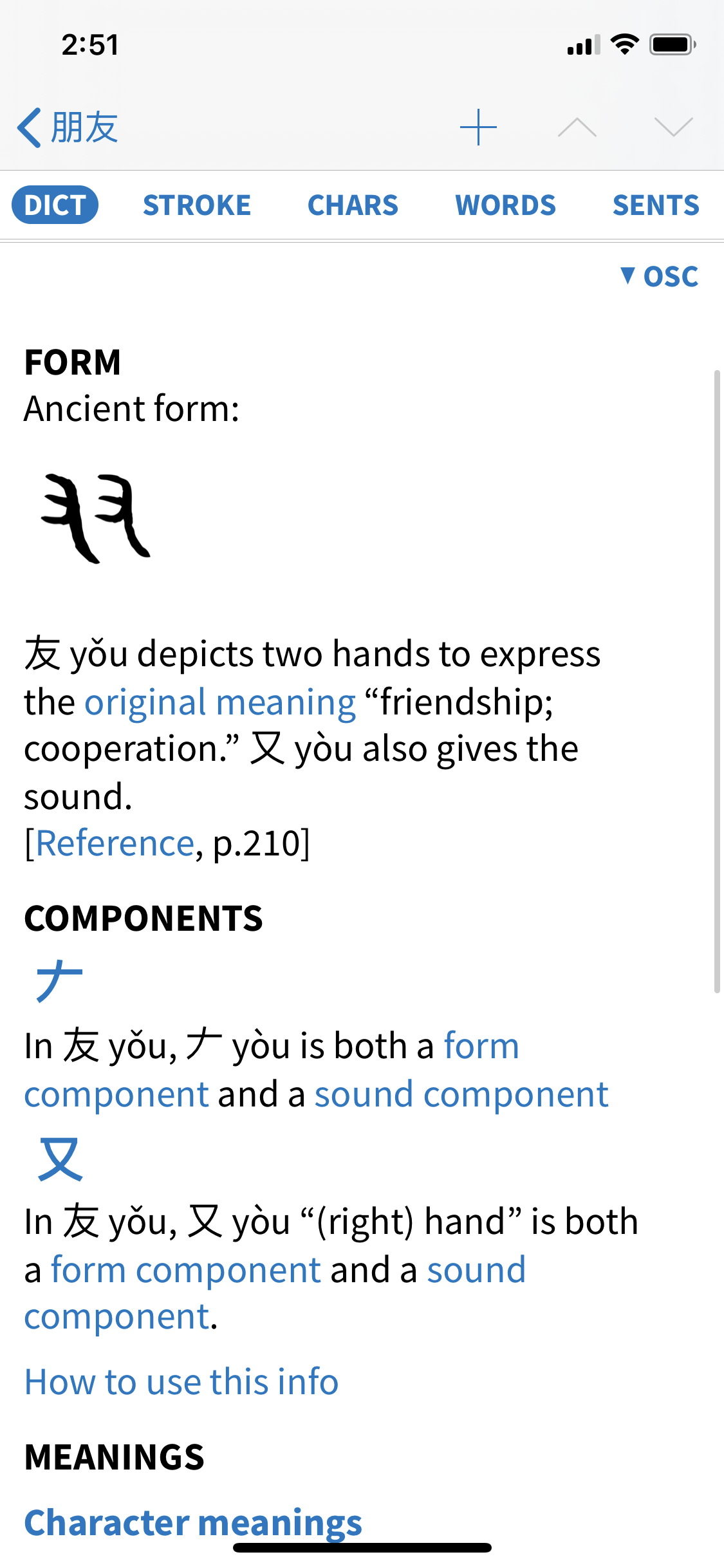

If you’re a serious student of Chinese, you probably know about the Outliers Chinese Dictionary for Pleco. Here are the entries for those characters:

你 (nǐ):

是 (shì):

我 (wǒ):

的 (de):

Not in my Outliers Dictionary. This explanation is from Wenlin:

In ancient times 的 meant ‘white’. Therefore 白 bái ‘white’ is a component in 的 (white: bright: clear: precise: bull’s-eye). 勺 sháo (‘spoon’) is phonetic: ancient 勺 *tsiak (modern sháo) sounded like ancient 的 *tiek (modern dì).

朋 (péng):

友 (you):

Holy crap. Don’t try to tell me that’s not a nightmare. It might be OK, if these were some cherry-picked exceptions, but they’re not, really. There are quite a few more common characters like this, although most characters are easier to make sense of when you break them down.

Try looking up the characters in this simple sentence if you want more trouble: 你不要说话! (Nǐ bùyào shuōhuà!)

Conclusions

The unfortunate truth is that many super-common characters have historical origins that are elusive to beginners, to put it nicely.

This is not the end of the world, though! If you’re in “Diligent Heisig Mode,” this is how you approach the “你是我的朋友” sentence above:

- 你: OK, the “person” radical is meaningful. That’s something! I’ll just have to deal with the right side somehow, since the character origin is useless to me.

- 是: All right, we have a “sun” (which I know!) and another component. This is a challenge, but it’s such a super-common word, that I can accept brute-forcing it into my memory somehow.

- 我: Yikes, a similar situation to 是, but with a much crazier form. Fortunately, there are not many of these.

- 的: Two clear components, and this is the #1 most common character in the whole language. So yeah… my memory can make an allowance for this one.

- 朋: OK, now we’re getting somewhere. A doubled-up component meaning “friend.” I can work with that.

- 友: Recognizable components. OK.

It gets easier, but there are a few speed bumps in the beginning. It’s for this reason that it can be very useful to not force yourself down that etymology rabbit hole for every new character you learn.

Most characters are composed of a sound component and a meaning component (they are called phono-semantic compounds), but the examples above are not so helpful in that way (even if some of them technically have a sound component). In any case, in order to “break into” the system and get it working for you, you have to do the work to learn the character component parts. Then the magic can start.

In conclusion: learn your character components (but not necessarily their full origins), and stay diligent. Your future Chinese literate self will thank you.

P.S. All my clients at AllSet Learning are strongly encouraged to become literate in Chinese using an approach similar to what I’ve discussed above. Feel free to get in touch.

P.P.S. I also discussed the Heisig method with my co-host Jared in our podcast, You Can Learn Chinese.

24

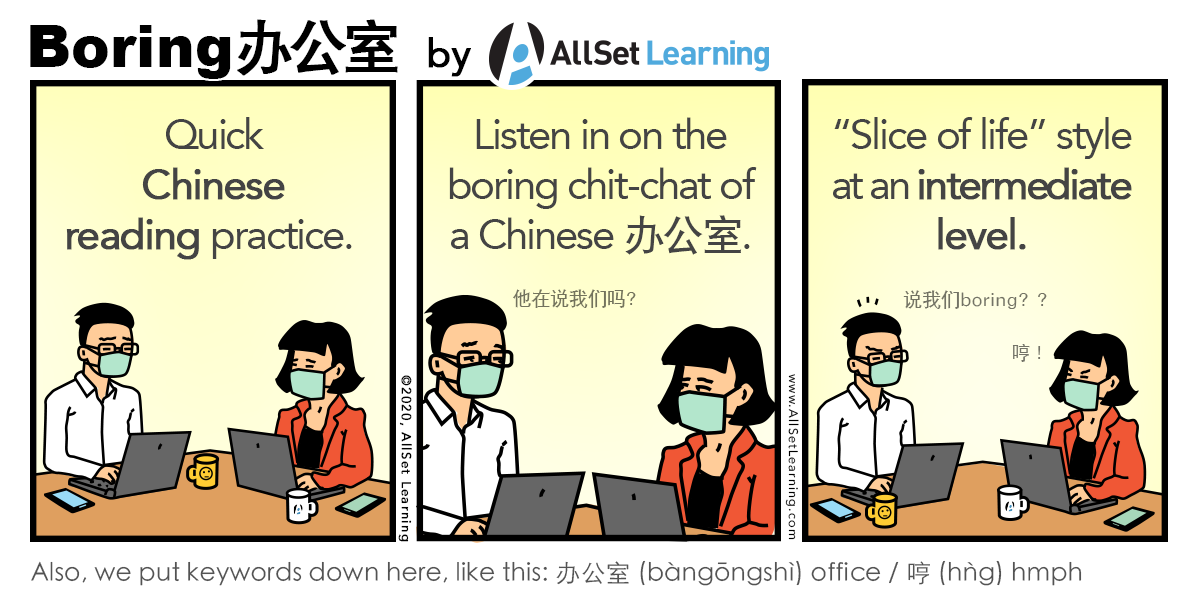

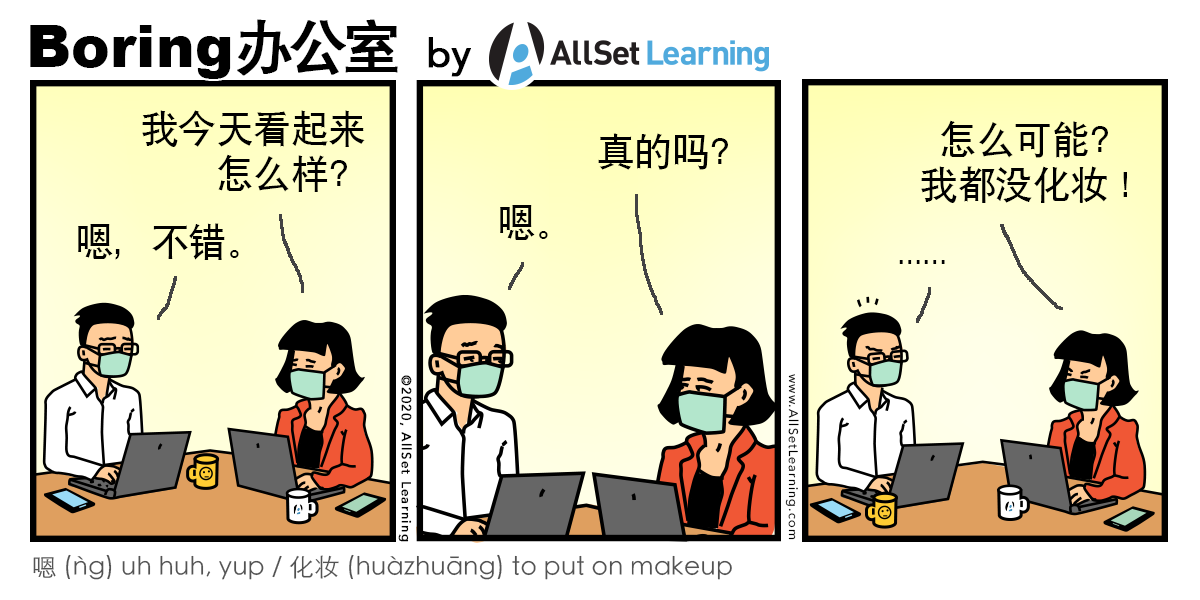

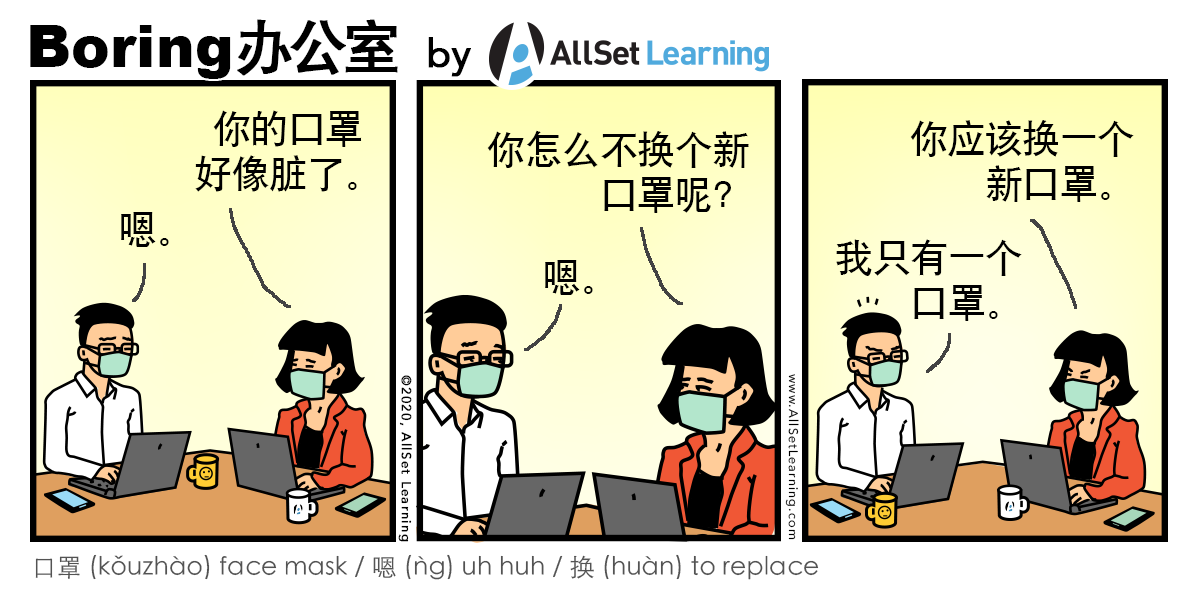

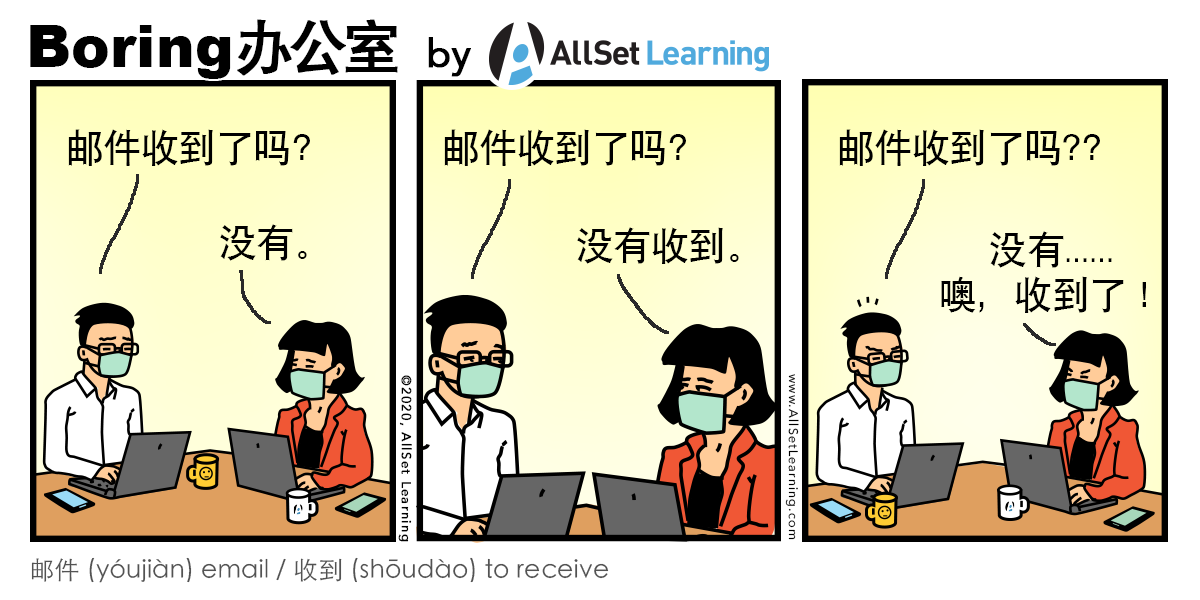

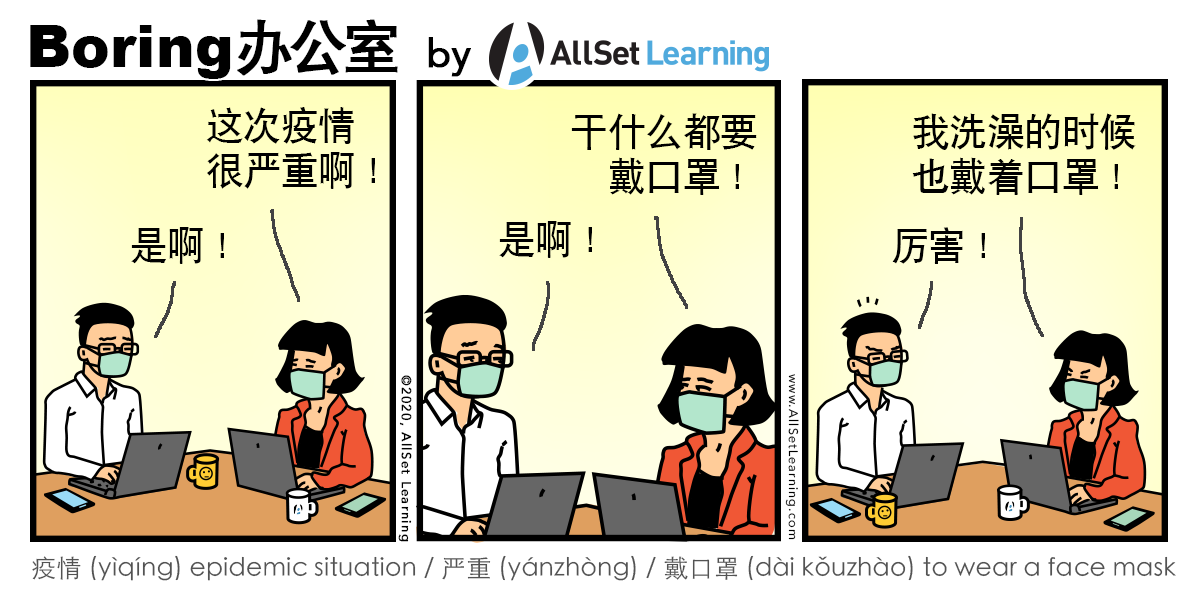

Mar 2020Boring Bangongshi: the Chinese Office Comic for Learners

So the team here at AllSet Learning has created a new thing! It’s an office-centric comic strip giving learners little bite-sized chunks of office language, and it’s called Boring 办公室 (Bàngōngshì). It was not originally intended to be COVID-19-focused, but it kind of turned out that way (for now).

Here’s the intro:

And here’s a taste of the comics:

You can click through each comic to get the full text of the dialog, grammar links, editor commentary, etc.

We just launched it, and there are plenty more comics in the pipeline.

So, please: share, discuss, criticize! If you read it, don’t find it funny, but keep reading, that is a win! We’re just trying to create material that learners don’t mind reading, at a level slightly higher than what’s more widely available (but still not too high).

Boring 办公室 (Bàngōngshì).

19

Mar 2020In Money We Trust

Pretty sure this is unironic?

The name of the shop is 钱店, literally “Money Shop.” This is one of those cases where traditional characters (錢店) are used in mainland China for stylistic effect.

This is a clothing and accessories shop near Zhongshan Park in Shanghai.

17

Mar 2020Unwarranted N-Word: Crimes of Song Lyric Translation into Chinese

I’ve been using QQ Music for years already. It’s one tenth of the cost of Spotify, and it has almost all of the songs I want to listen to (plus no VPN required!). It has English lyrics for most of its songs, and sometimes even Chinese translations of those English lyrics.

I’m quite the reader of song lyrics, and sometimes QQ Music lets me down in weird ways. The first way is just bad translation. Song lyrics are a translation challenge no matter what, and I’m forgiving, but sometimes the translations into Chinese are just plain bad.

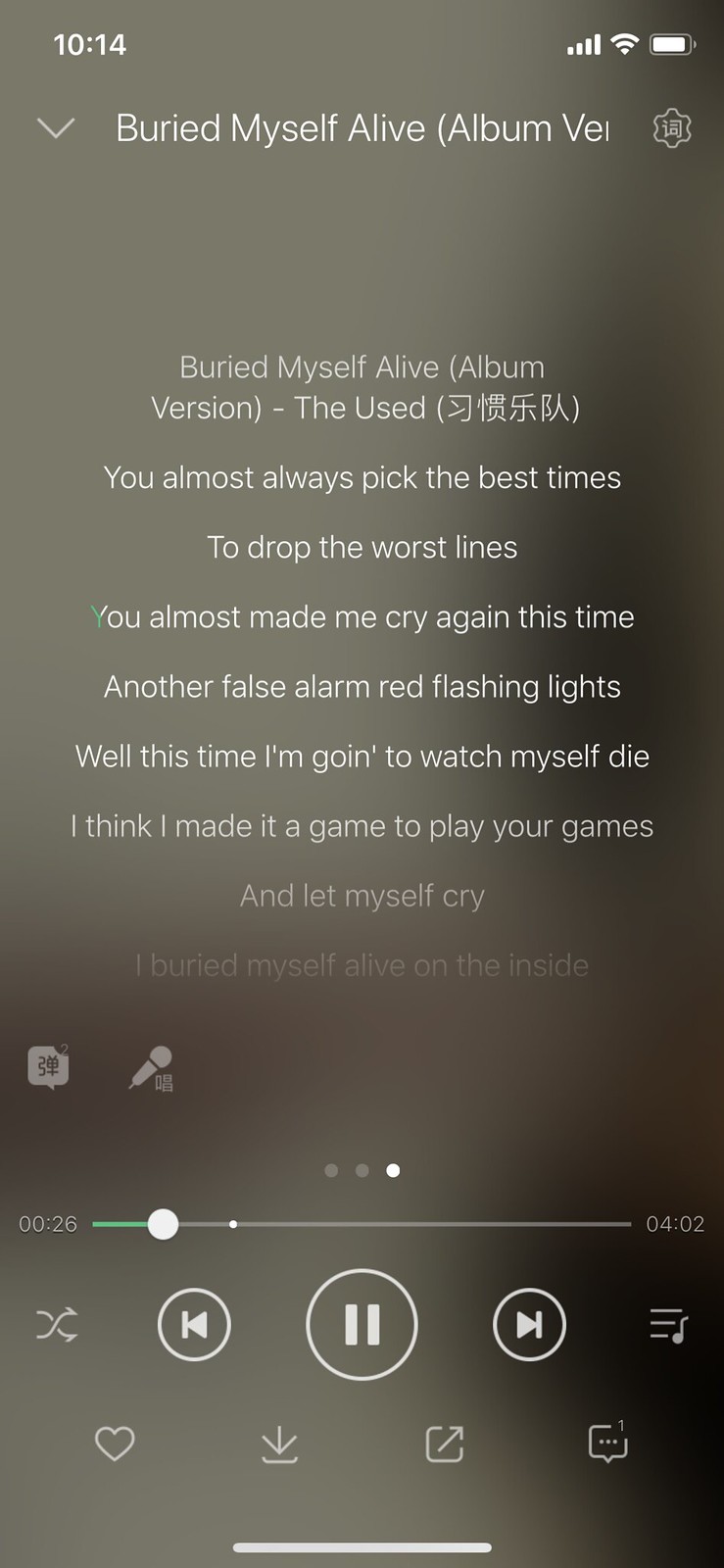

The Used

Do you remember that emo band called The Used? Here’s a YouTube video to refresh your memory:

Anyway, what do you think this band’s Chinese name is? Translated literally, it would be something ridiculous like 被利用着. Nope. This is it:

习惯乐队. 习惯 as in “customs” or “habits,” and 乐队 as in “band.” The word 习惯 also means “to get used to” (doing something), so some translator got the words right, but badly misunderstood the meaning of the band’s name. I guess he was thinking the band’s name meant something like “Getting Used to It”?? No idea.

This kind of translation mistake is fairly common on QQ Music, but not common enough that it bothers me too much.

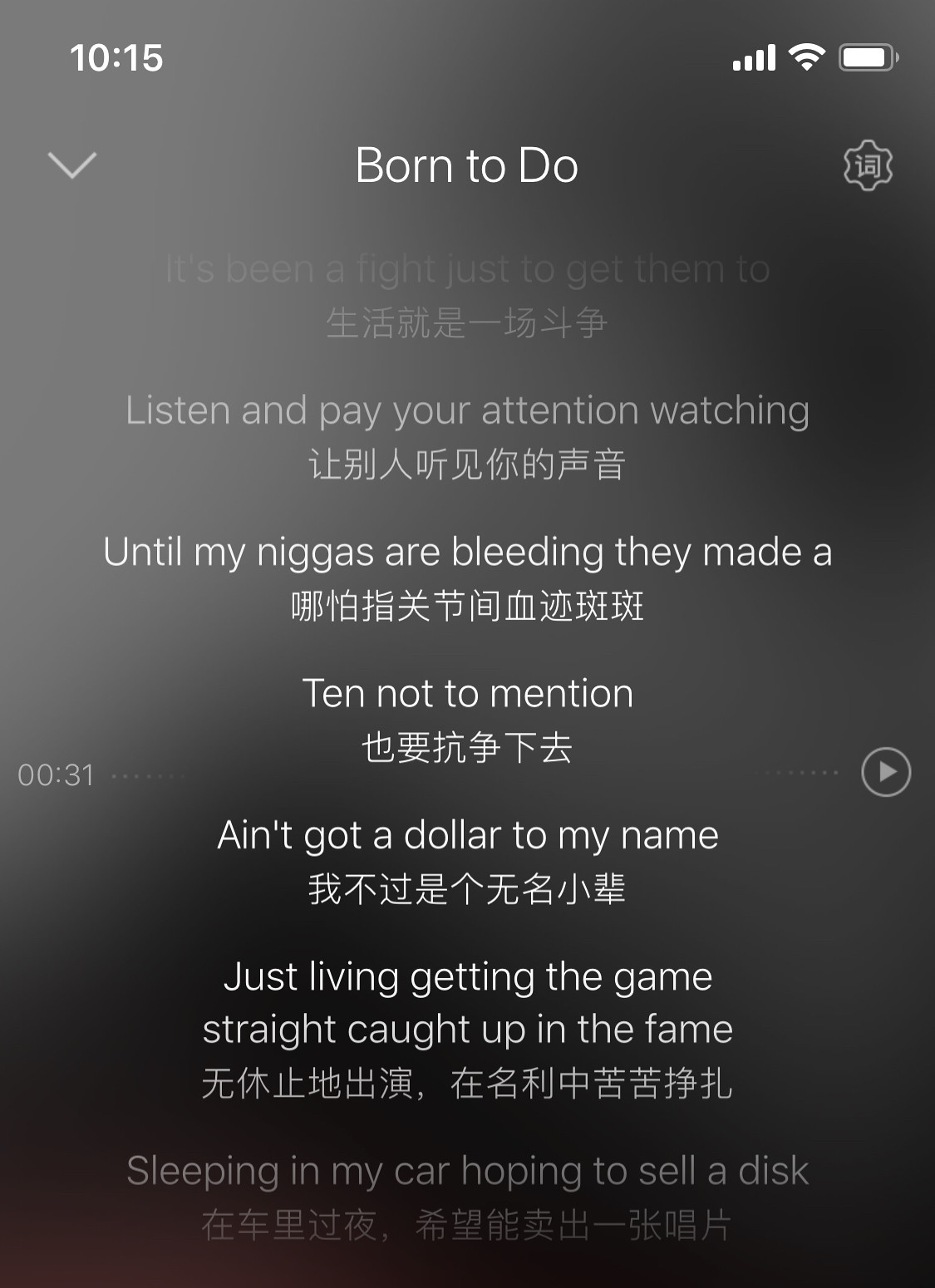

Perplexing Use of the N-Word

This next mistake, concerning Steven Cooper’s song “Born to Do,” really had me confused, though:

I randomly came across this song on QQ Music, and my kids liked it. I did a quick lyrics scan, and didn’t notice any bad words, so we listened to it. It wasn’t until after listening to this song several times that I read the lyrics carefully and discovered the N-word.

I was pretty shocked, because this is a Christian rapper. WHY did he feel the need to use that word (just once) in this song?? It didn’t make any sense.

The more I thought about it, though, the more I realized that the lyric itself didn’t make any sense, and not just because of a bad transcription:

Locked in this room off through the night

Trying write

Every second of my life in this mic

It’s been a fight just to get them to

Listen and pay your attention watching

Until my n****s are bleeding

Wait, what? Who’s bleeding and why? It’s a song about how hard he tries to improve his skills at rapping because it’s what he was “born to do.” This particular part of the song is about writing.

So yes, the “n-word” here should have been “knuckles.”

How could such an offensive mistake happen? I’m sure a Christian rapper with clean lyrics takes care not to drop gratuitous N-bombs in his song lyrics.

The best I can guess is that the lyrics are transcribed by machine, not be a person. It’s kind of weird that a computer would identify the N-word. I mean, you can’t have it popping up randomly in Celine Dion songs or Disney lyrics, right? But maybe if a song is classified as rap, then the “ban use of the N-word” toggle is switched off.

Here’s how that section should have gone:

Locked in this room all through the night

Trying to write

Every second of my life in this mic

It’s been a fight just to get them to

Listen and pay attention watching

Until my knuckles are bleeding

There’s one final strange thing happening here, though… Although the English lyrics contain the N-word, the Chinese lyrics contain a translation of the word for “knuckles”: 指关节.

…and now I am totally at a loss to explain this!

11

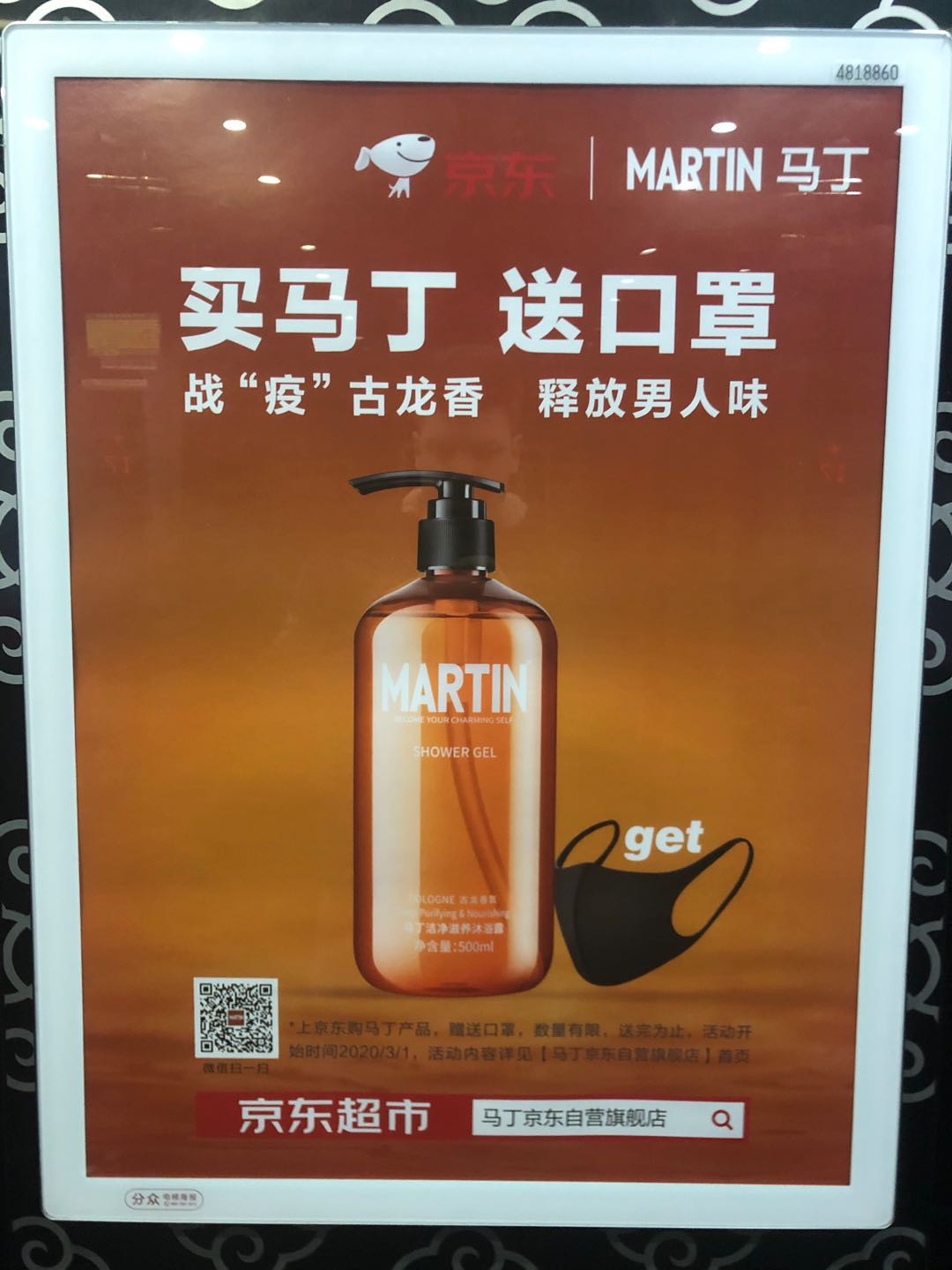

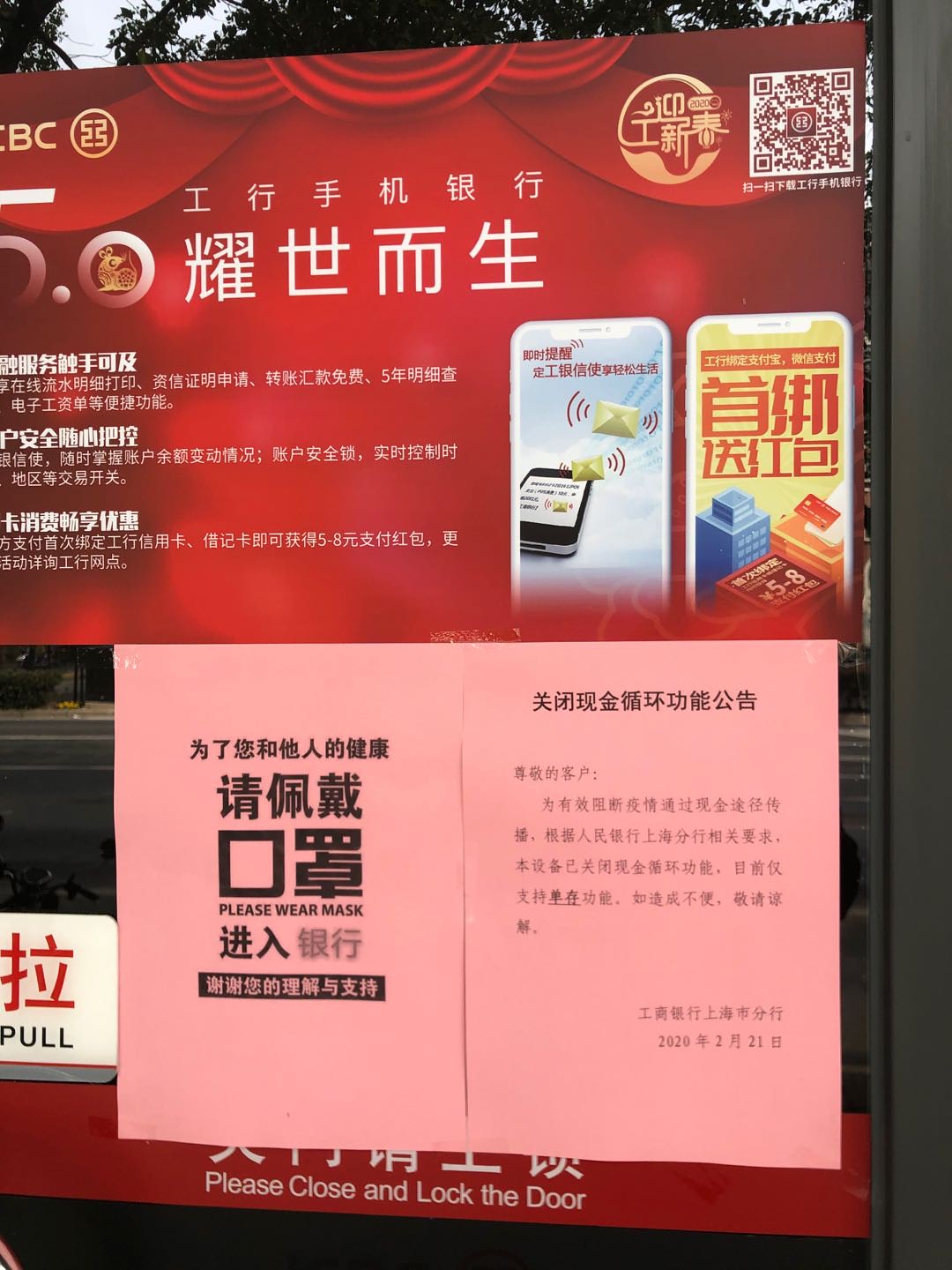

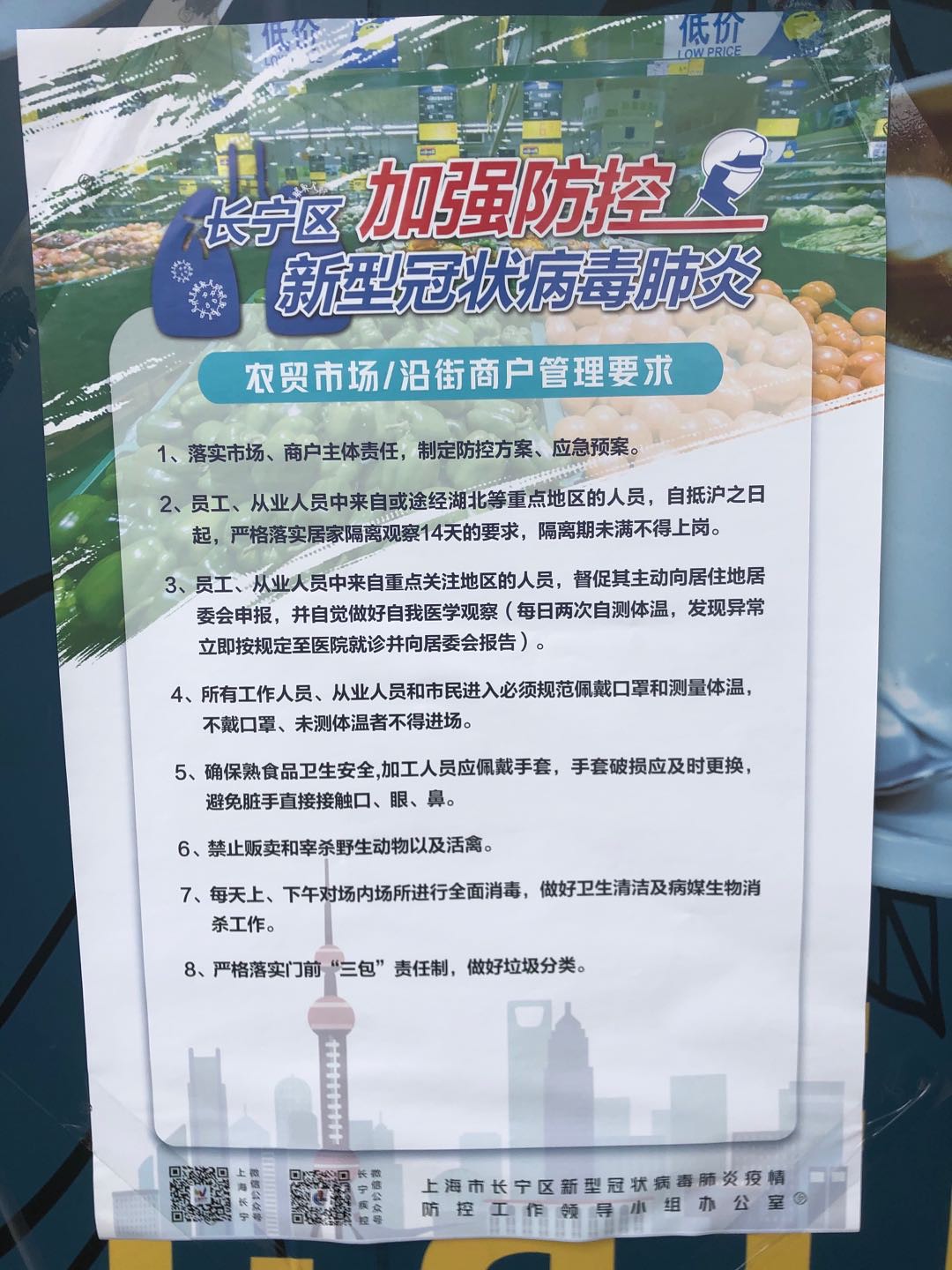

Mar 2020Coronavirus Lockdown in Shanghai: One Month In

I came back from Chinese New Year holiday in Nagoya, Japan on February 10 to a Shanghai already in lockdown over the novel coronavirus, now known as COVID-19. I’ve been getting lots of questions from friends all over the world about how things are going in Shanghai (especially as the virus continues to spread globally), so I decided to share a bit more about our situation in Shanghai, one month in.

Work

The official CNY holiday was extended, and we started working from home after that, until February 14th. The following week, starting February 17th, we returned to the office to lots of required face masks, registration, and disinfectant. Very few people were at the office, and one of my co-workers was still in 14-day self-quarantine after returning from Shandong. It was easy to avoid human contact! Only one of my co-workers elected to keep the face mask on in the office.

It’s March already. All the same protective measures are in place, but with a bit less “vigor,” you could say. More and more people are coming back to the office, but the morning line for the elevator is nowhere near what it was yet. (I suppose a lot of companies are discovering that working from home isn’t that bad?)

AllSet Learning‘s face to face consultancy for learning Chinese has definitely taken a hit, as many of our clients are either (1) not back in Shanghai yet, choosing to wait out the virus abroad (not sure that’s going too well!), or (2) dealing with a lot of uncertainty and craziness for work due to the virus, and thus not able to do lessons. One client even left China with his family around CNY and decided not to come back.

Fortunately, AllSet is doing more and more online lessons as well as other products, so we’re able to weather this storm. One thing that would make this ordeal much easier is a reduction in our office rent, but our landlord insists that he hasn’t gotten a break in rent from the office building owner, and thus can’t give us one. Other tenants pushing for it hasn’t helped, either. Situations like this make the economic cost of the virus quite lopsided.

My wife has been doing a rotating thing where in the first week, each person went into the office one day a week, and worked from home the other 4. Then 2 days a week in the office, 3 at home. This week it’s up to 3 days in the office, 2 working at home. Seems like a smart, cautious way to gradually increase the numbers of people at the office while also monitoring and controlling possible infections.

School

My kids are at home through all this. My son is young enough that the missed school doesn’t really matter, but my daughter in second grade has been doing regular online lessons since last week (with homework). It seems like she’s even learning something!

So we haven’t had to pay for my son’s tuition at all yet this semester, but my daughter’s was paid (a bit late, while they figured everything out). It’s unclear how the school semester is going to play out. I had a fun summer vacation planned in the US, but that’s all been canceled. I fully expect the school year to be extended into the summer to make up for missed school (and low efficiency of the online methods tried so far). Canceling summer vacation would be such a China thing to do, unfortunately…

It’s still cold outside, so my kids aren’t super stir-crazy yet, but they’re not getting enough exercise.

Home

The main differences at home are:

- The kids are home, all the time.

- When you have food or packages (kuaidi) delivered, you have to go out to the front gate to pick it up (the delivery guys are not allowed in).

- When you go in or out of the compound, you need to wear a face mask (I tested this going out one morning last week, and the guard wouldn’t let me out of my own compound without a mask on!).

- Every time you come back into your compound, your temperature gets taken.

If you leave your own apartment and stay within the compound, no one really says anything if you don’t wear a face mask.

Some pictures of various apartment complexes around the Shanghai Zhongshan Park area:

Around the City

I got that haircut on February 19th, but for the most part, barber shops are still closed. The ones that are open are the small independent ones. The big chains like Yongqi and Wenfeng are all still closed.

Most restaurants have gone into “take-out only” mode. Starbucks, one of the first well-known brands to announce store closures, is a good example. After closing for 1-2 weeks, Starbucks reopened in “take-out only” mode. Just to step inside the store, you have to be wearing a mask and have to consent to your temperature being taken (this is the new norm for essentially any public building).

Still, many of the restaurants remain fully closed. I assume that many of the smaller ones will not be reopening at all.

I haven’t used any taxis (or Didi) at all yet this year, except for the airport taxi on February 10th. But public transportation seems to be working just fine. You just need to wear a mask, and there’s a temperature check for the subway.

Signs related to COVID-19 are everywhere, such as reminders that wearing a face mask is a requirement to enter a building.

In general, the overall atmosphere in Shanghai is resignation or possibly annoyance. There was some minor panicking going on over COVID-19 about a month ago, and I saw rumors flying around in WeChat, spread irresponsibly. But now things are a lot calmer. Obviously, economic worries are very real as well. We’re just waiting for things to go back to normal… if that’s what’s next.

Related: Download the COVID-19 Vocabulary PDF on this page.

06

Mar 2020Hubei Automobile Profiling?

Just another sign of the effect the coronavirus has on people:

The Chinese reads:

本车近一年

未去过湖北

The English translation is:

This car has not been to

Hubei for close to a year

The character 鄂 (È) on the license plate is the one-character abbreviation for Hubei.

I do wonder if there’s a story behind the owner of this car putting that sign up. What did his panicked compatriots do?

Related: Download the COVID-19 Vocabulary PDF on this page.

04

Mar 2020Gal Gadot in the Shanghai Subway

The last time this company’s ads featured Chloe Bennet (star of Marvel’s Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D.). Well, it seems they have a thing for female superheroes, because now Gal Gadot (AKA Wonder Woman) is all over the Shanghai Metro.

I didn’t notice this until I looked up my old blog post, but it’s kind of funny thing that she’s wearing almost exactly the same outfits as Chloe Bennet was.

I’m well aware that little boys in China loooove Marvel superheroes (my own 5yo is one of them). Aside from Hulk, Iron Man, Spider-Man, etc., they also love Captain America. I always thought this was kind of funny, since China is pretty nationalistic and has a complicated relationship with the USA. No one seems to think anything of it, though. And the love extends well into adulthood… plenty of young men are totally into Marvel superheroes, obviously (those movies sure do well here).

So this ad campaign makes me wonder how into female superheroes Chinese women are. Is that a thing? Or are they just two attractive Hollywood stars that wound up in ads in China?

27

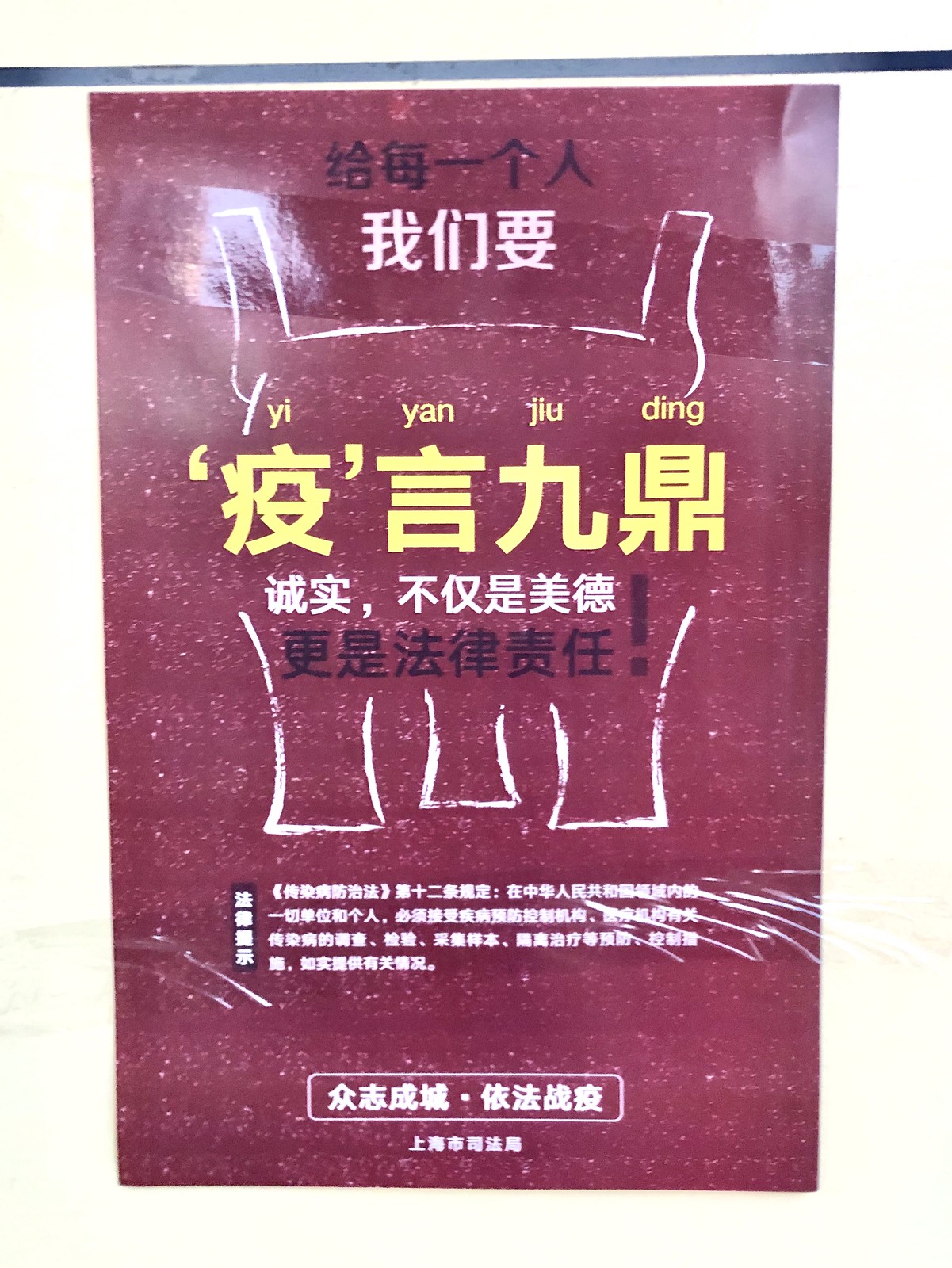

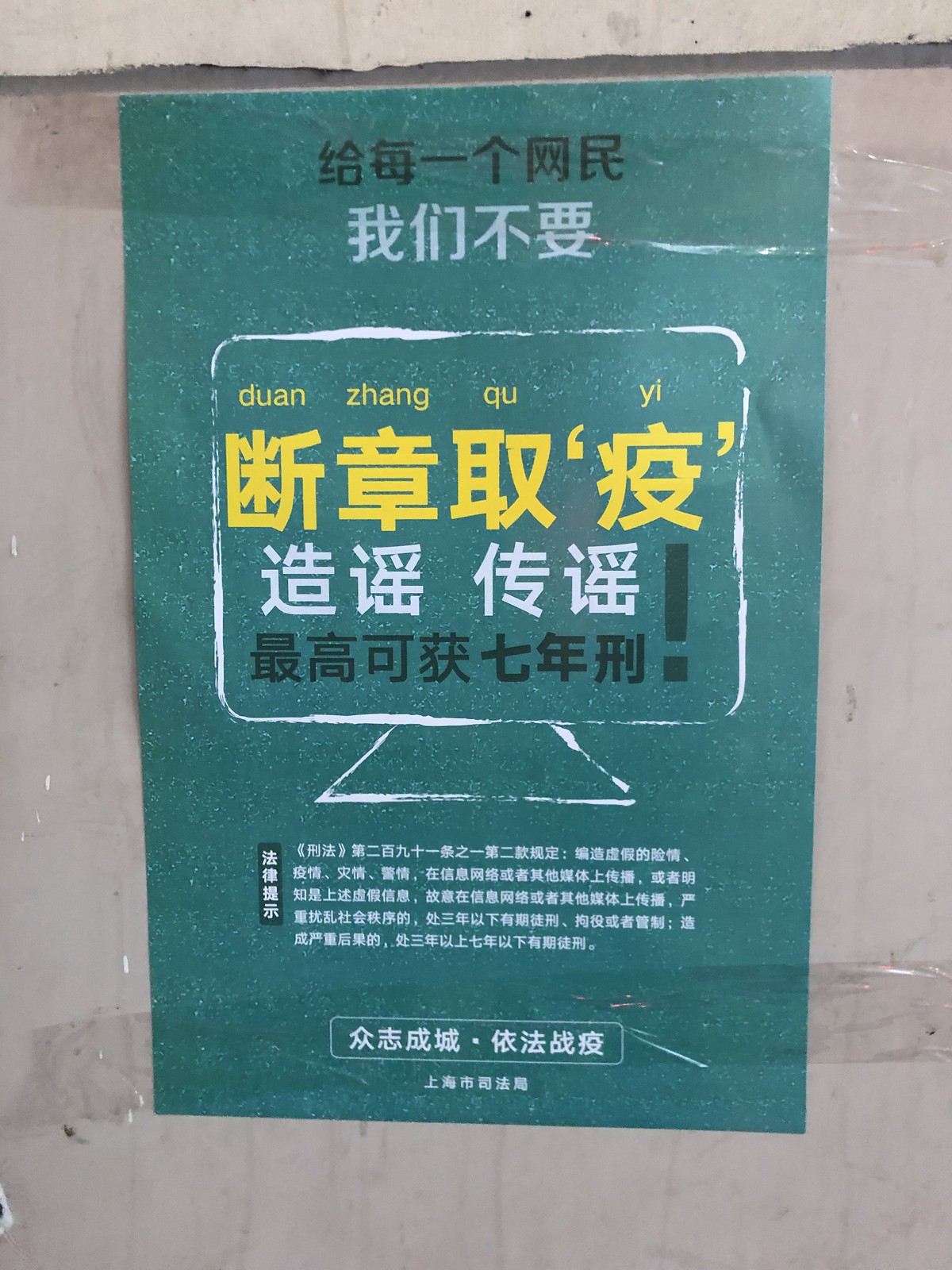

Feb 2020Combatting the Coronavirus with Punny Propaganda

Three exhibits from the streets of Shanghai, each replacing one “yi” character of a chengyu (typically 4-character idiom) with the character 疫 (yì), which means “epidemic”:

‘疫’言九鼎 is a pun on 一言九鼎 (yīyánjiǔdǐng). The original idiom refers to solemn statements, and the poster exhorts people to be honest (about their true health).

断章取‘疫’ is a pun on 断章取义 (duànzhāngqǔyì). The original idiom refers to quoting out of context, and the poster warns people not to spread unsubstantiated rumors about the epidemic (you could end up in prison for as long as 7 years if you do!).

仁至‘疫’尽 is a pun on 仁至义尽 (rénzhìyìjìn). The original idiom refers to fulfillment of moral obligations, and this poster implores people to remain compassionate while battling the epidemic.

In all fairness, “yi” is one of the most common readings for characters in Mandarin Chinese, so choosing that one to focus on with the puns really made things easier.

Related: Download the COVID-19 Vocabulary PDF on this page.

20

Feb 2020Not the Usual Haircut

All kinds of stores and shops in Shanghai have been closed for weeks. This past Tuesday, I went for a walk and noticed that a few barber shops were open. Yesterday I decided to finally get my first haircut of 2020.

It was a somewhat unusual haircut.

They took my temperature first. Everyone in the place wore a face mask (which has to be partially removed during the haircut to cut around the ears), and there was lots of disinfecting between haircuts.

Hopefully we’ll put this coronavirus affair behind us soon. March 2020 is looking much better than February!

Related: Download the COVID-19 Vocabulary PDF on this page.

11

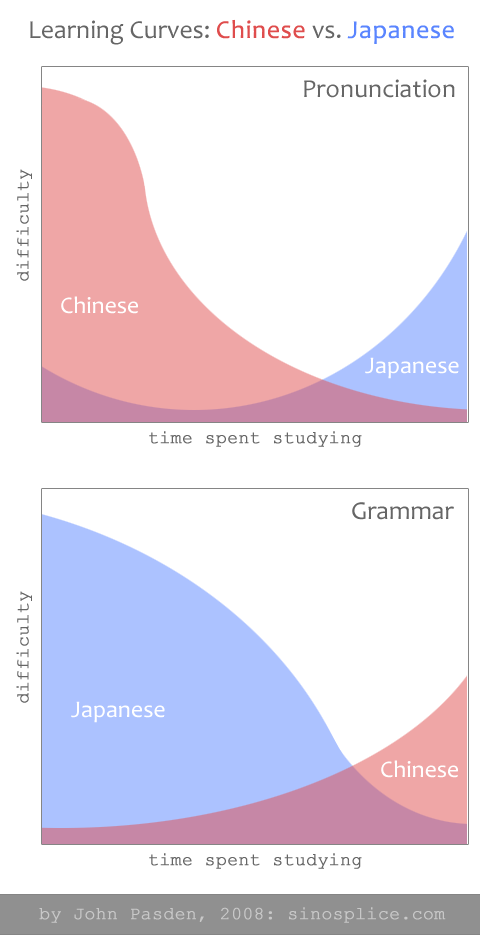

Feb 2020Japanese Pronunciation Challenges (totally different from Mandarin Chinese)

A while back I wrote about how learning Chinese compares to learning Japanese, difficulty-wise. It’s generated a lot of interest, but one point which many readers may not have fully understood was why the Japanese “pronunciation difficulty” line rises towards the end. Refer to the graph here:

So… What makes it more difficult when you study long enough? This is what I originally wrote:

Japanese pronunciation is quite easy at first. Some people have problems with the “tsu” sound, or difficulty pronouncing vowels in succession, as in “mae.” Honestly, though, Japanese pronunciation poses little challenge to the English speaker. The absolute beginner can memorize a few sentences, try to use them 20 minutes later, and be understood. The real difficulty with Japanese is in trying to sound like a native speaker. Getting pitch accent and sentence intonation to a native-like level is no easy task (and I have not done it yet!).

Recently I discovered YouTuber Dogen. He’s got a bunch of really great videos on advanced Japanese pronunciation, and this once does a great job of summing up and illustrating the 4 main types of Japanese pitch accent:

Got it?

I don’t know about you, but I never studied Japanese pitch accent in depth as a student. Not as a beginner, and not as an intermediate to advanced student. I remember I learned what it was, but it was never given a lot of emphasis. It really does seem to be something you typically tackle once you’ve confirmed that you’re a super serious learner, and “just making myself understood” isn’t enough anymore.

This contrasts with Chinese, where the 4 tones are thrown in your face from the beginning (there is no escape), followed closely by the tone change rules.

Interestingly, when Chinese learners in China study Japanese in school, they do learn pitch accent from the get-go, and the result is much more native-like pronunciation from a much earlier stage. I’ve witnessed this, and it’s impressive. Freeing up learners from the burden of kanji (Chinese characters in Japanese) means that time and effort can be placed elsewhere. (Similarly, Chinese learners tend to be a bit weak on the non-character syllabaries of Japanese: hiragana and katakana, over-relying on their character recognition advantage to get them through reading.)

07

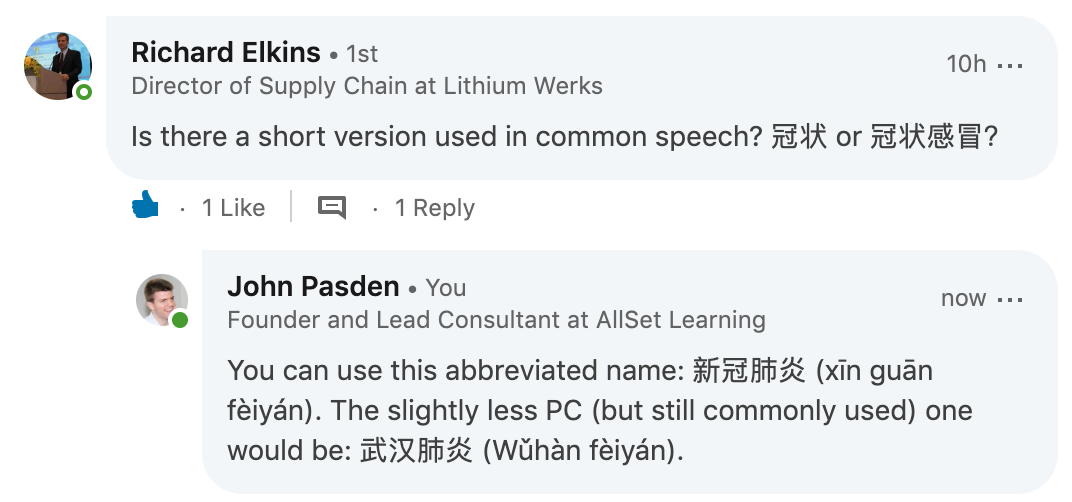

Feb 2020Chinese Nicknames for the Novel Coronavirus

After sharing the vocabulary about the coronavirus, I got a good question on LinkedIn about a shorter Chinese name for the virus. There are two 4-character names commonly used in Chinese:

- 新冠肺炎 (xīn guān fèiyán) lit. “New corona pneumonia”

- 武汉肺炎 (Wǔhàn fèiyán) lit. “Wuhan pneumonia”

I’m thinking about writing about the name a bit more, since there are so many variations. (Not the most exciting topic, I know, but it’s just so omnipresent these days…)

04

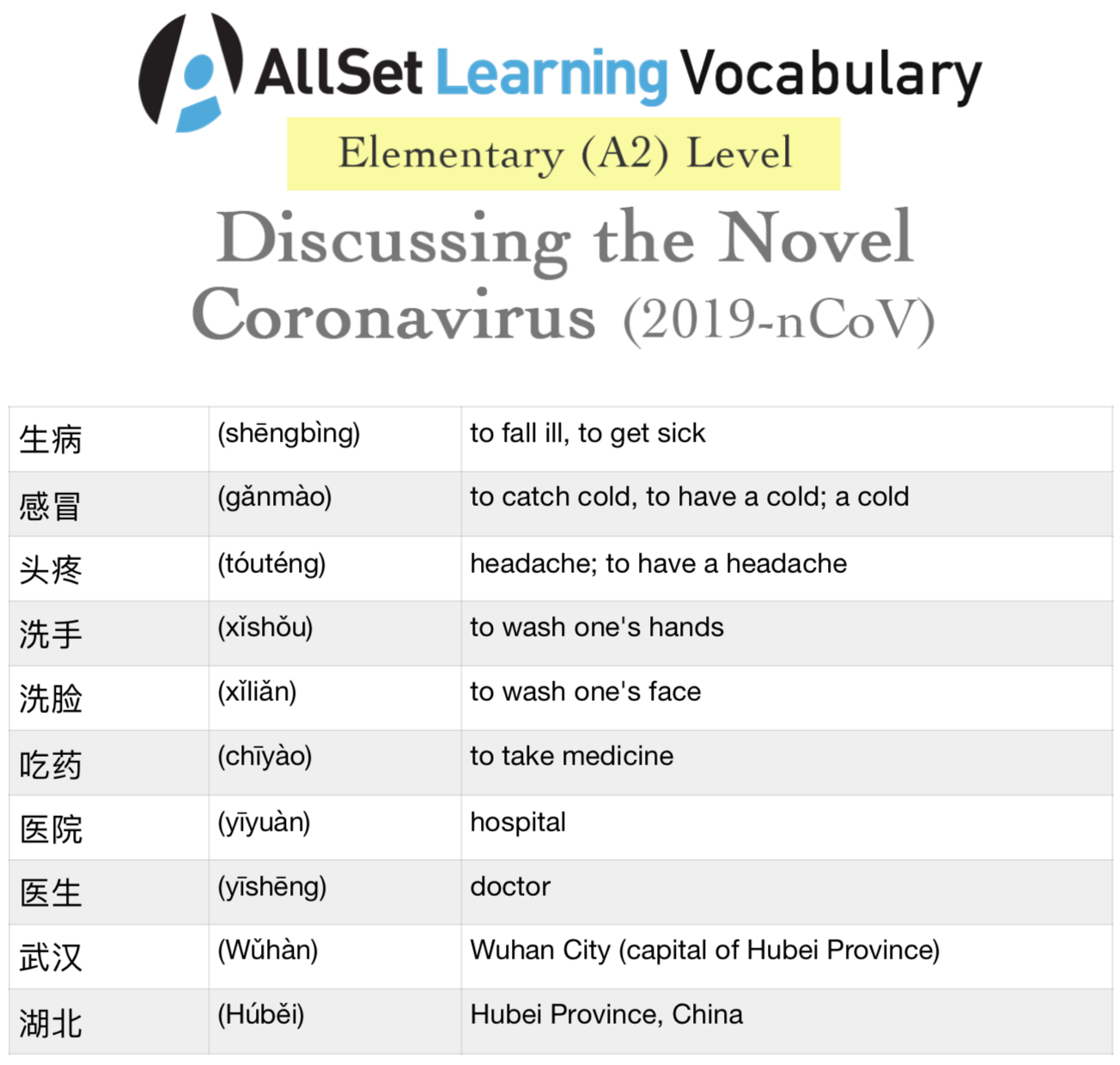

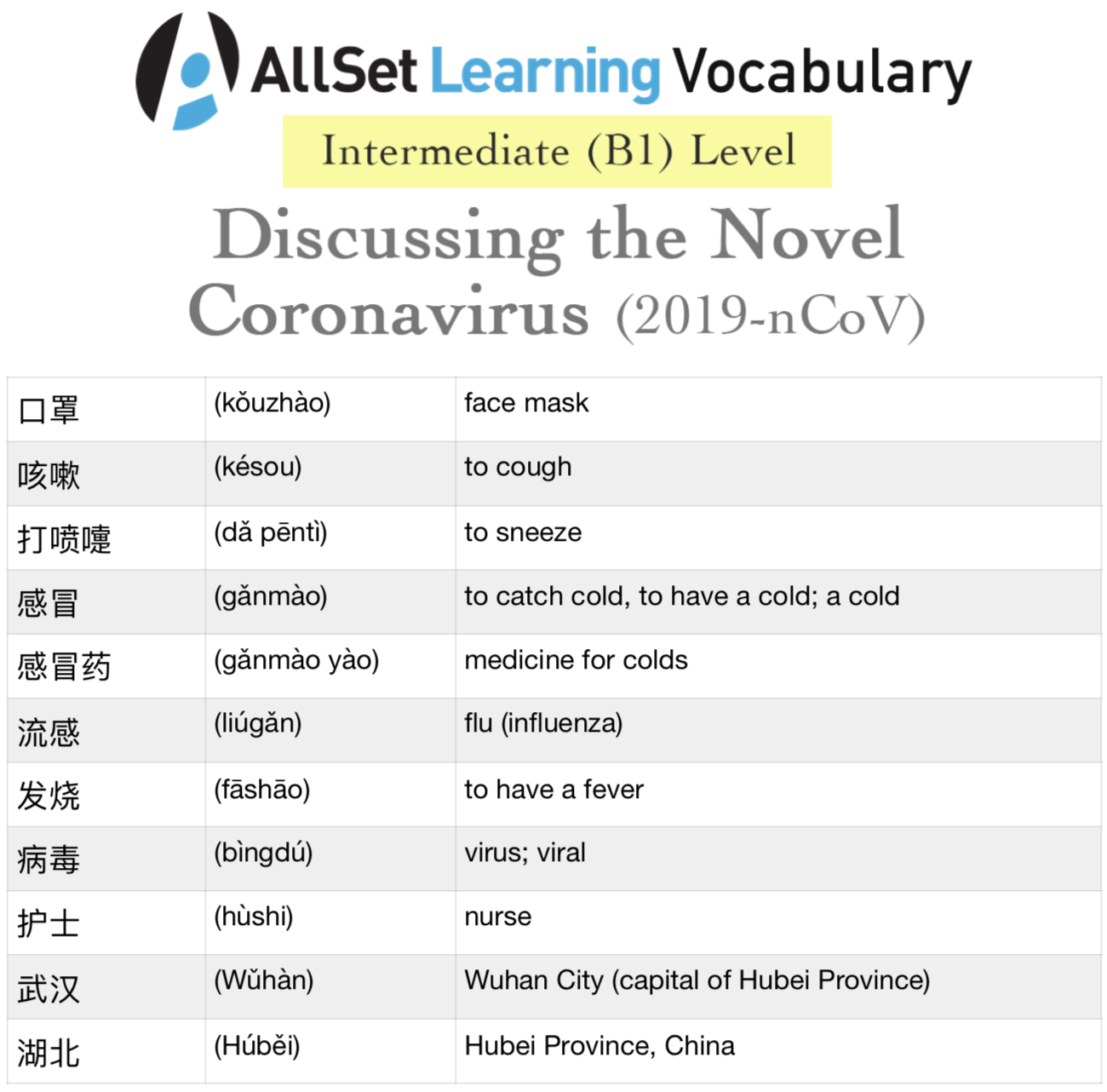

Feb 2020The Unavoidable Novel Coronavirus Vocabulary

When I returned with my family from Japan over the past weekend, China had changed. The spread of the coronavirus and the extensive efforts to shut it down had turned Shanghai into a ghost town. The topic absolutely dominates WeChat (and we all live in WeChat over here), whether it’s in one’s “Moments” (feed) or in various WeChat group chats, whether in English or in Chinese.

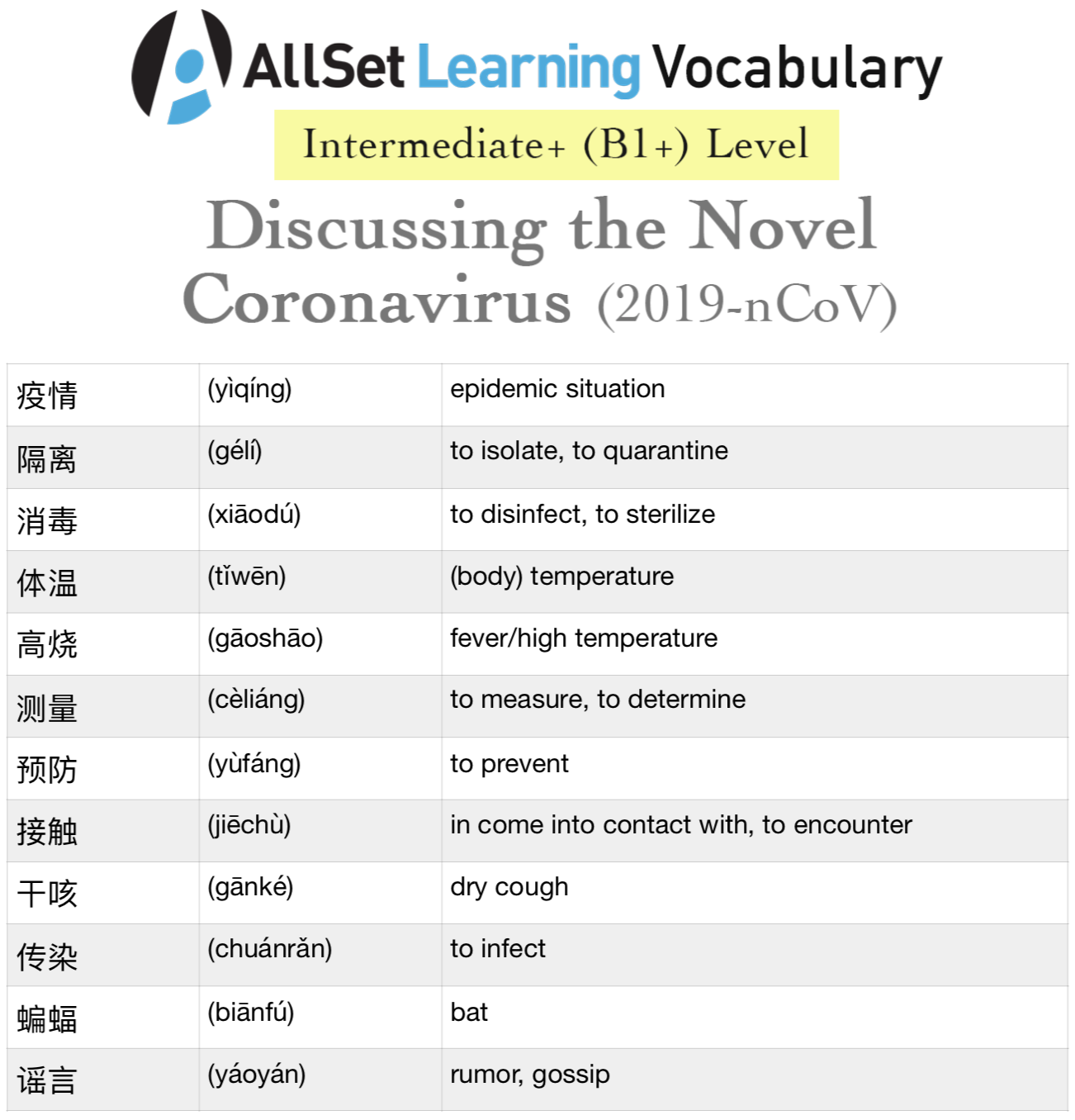

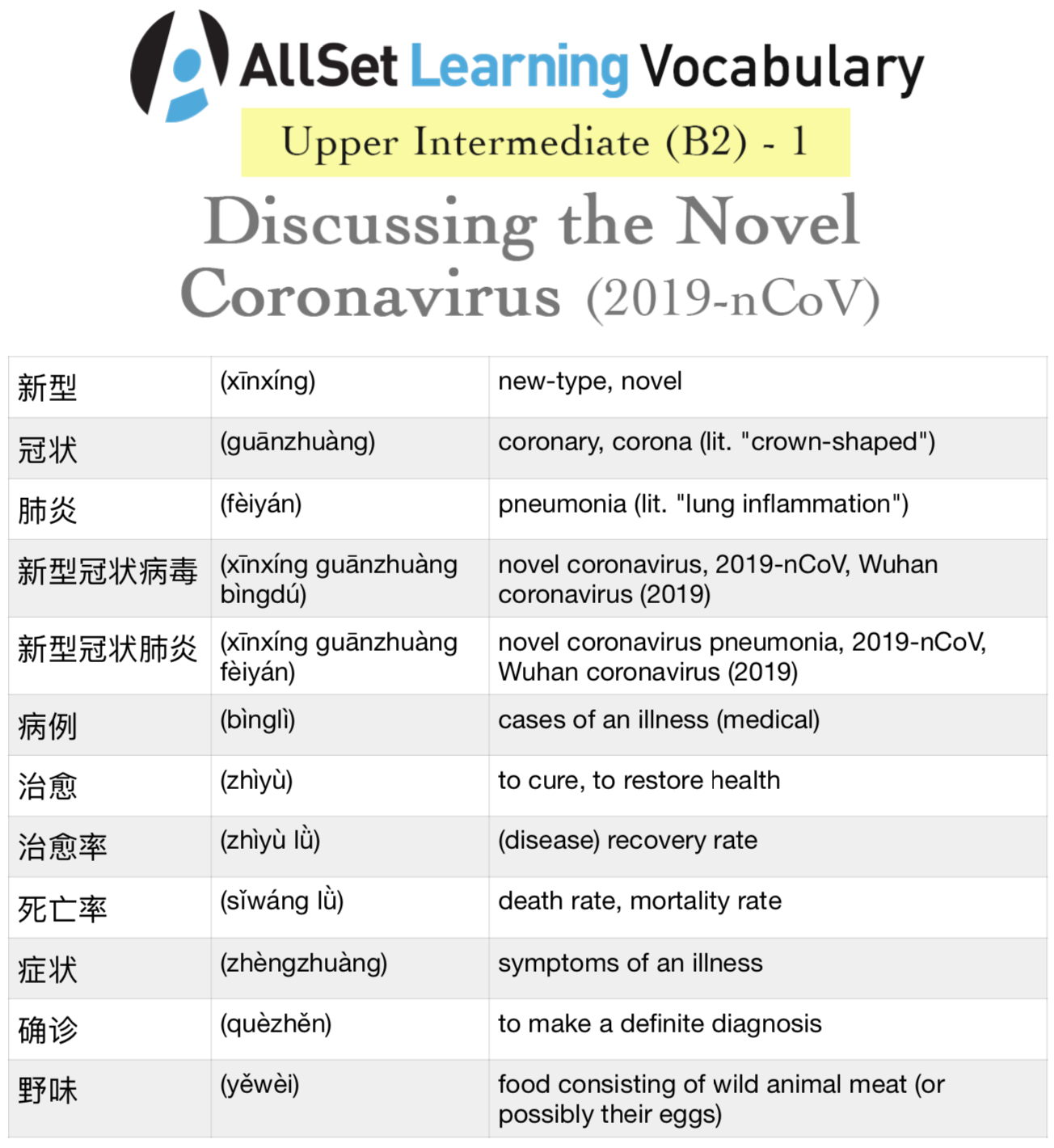

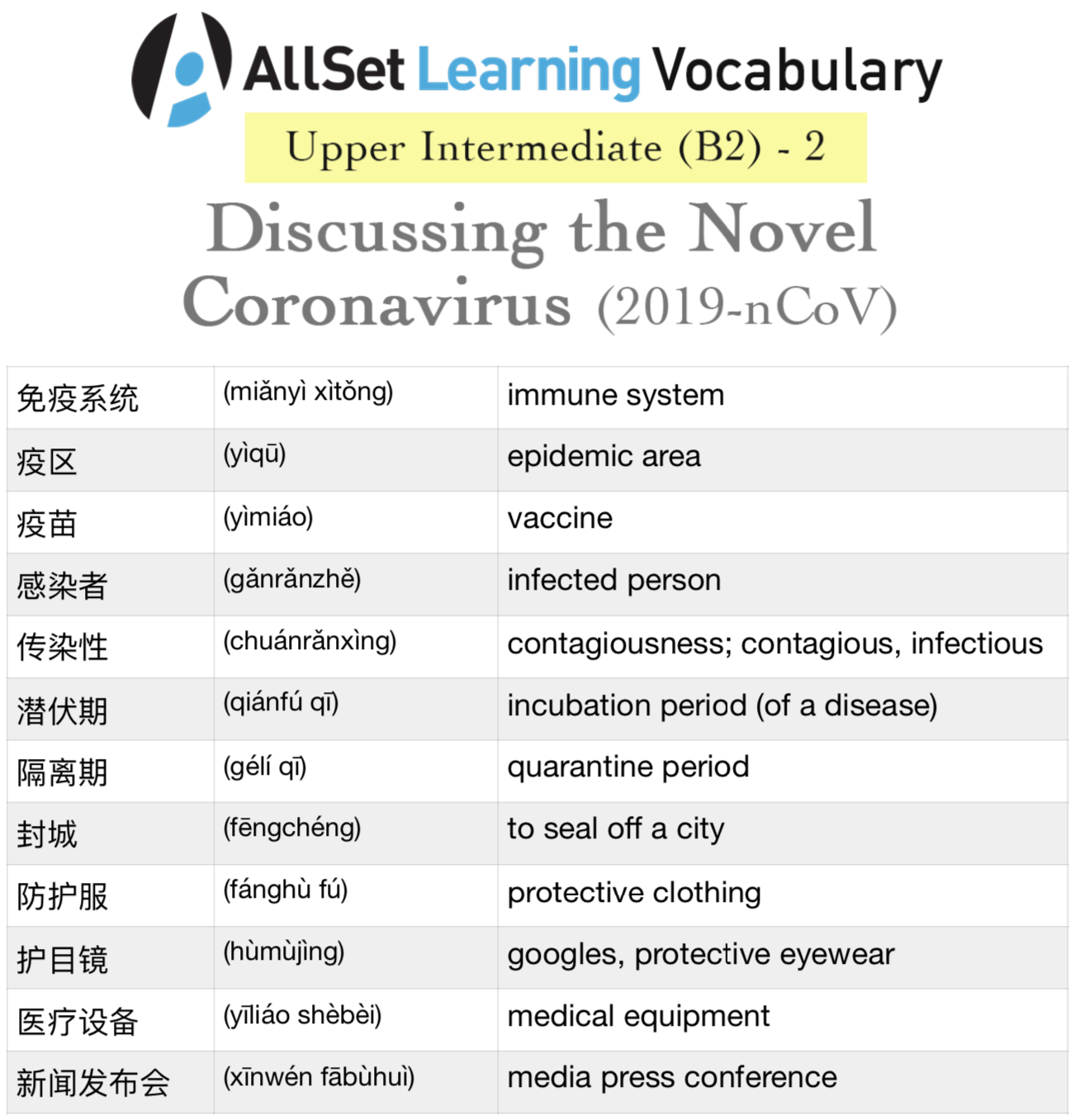

So my co-workers and I at AllSet Learning got to work creating a series of vocabulary lists to help learners of Chinese deal with this unavoidable topic. The lists are separated by level, so whether you’re only elementary or are already upper intermediate, there’s a list here for you! Do not try to study all the lists (unless you’re already upper intermediate and you’re just filling in little gaps).

Here are the lists in image form (easier to share), but there’s a PDF link at the bottom as well.

Download the COVID-19 Vocabulary PDF on this page.

23

Jan 2020Chinese New Year Quiz Time!

We’ve got lots of new stuff in the works at AllSet Learning, and sometimes it’s even relatively small projects that we can release quickly. The latest of those is our new quizzes. We’ll keep refining the core quiz app, but the first quiz is ready, just in time for Chinese New Year 2020:

Happy Chinese New Year! (Take the quiz, and if you like it, please share!)

16

Jan 2020Shanghai’s Chinese New Year Melancholy

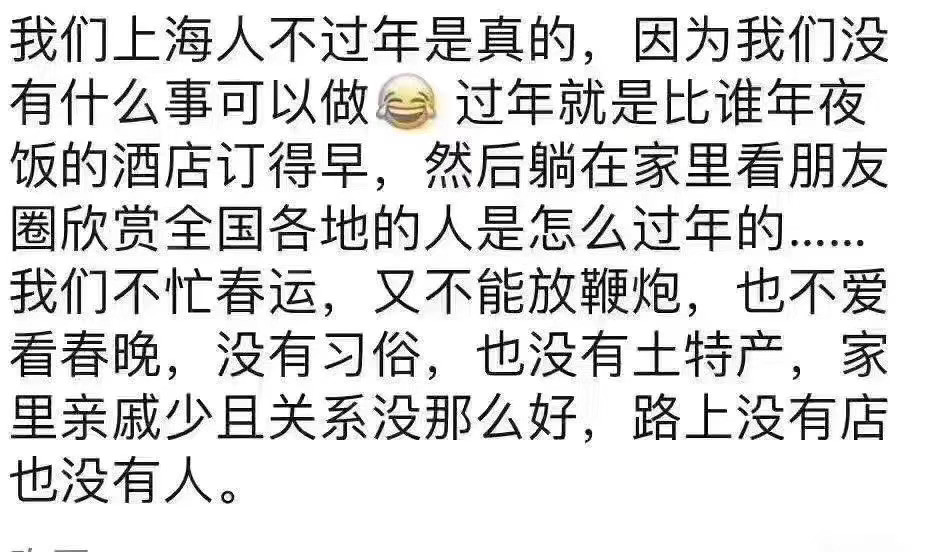

Recently a Shanghainese friend shared this screenshot on WeChat:

I’ll transcribe it below as text for you learners:

我们上海人不过年是真的,因为我们没有什么事可以做!过年就是比谁年夜饭的酒店订得早,然后躺在家里看朋友圈欣赏全国各地的人是怎么过年的……我们不怕春运,又不能放鞭炮,也不爱看春晚,没有习俗,也没有土特产,家里亲戚少且关系没那么好,路上没有店也没有人。

And a translation:

It’s true that we Shanghainese don’t really celebrate Chinese New Year because there’s not really anything for us to do! Chinese New Year is just competing who can make the earliest restaurant reservation for Chinese New Year’s Eve dinner [年夜饭], then lying around at home browsing WeChat Moments to see how the rest of the country is celebrating Chinese New Year…. We have no fear of the massive CNY migration [春运], and we’re not allowed to set off fireworks anymore. We don’t like the CCTV New Year’s Gala [春晚], and we don’t have any real traditional customs or local specialty foods. We have few relatives, and the ones we do have, we’re not on great terms with. There are no shops open or any people in the streets.

My immediate reaction was, “wow, this is so true! And sad!” I shared it with my co-workers, and a Shanghainese co-worker’s reaction was:

大实话。有时候我会羡慕赶春运的人们。

Translation:

So true. Sometimes I envy those people crammed into trains just to get home for Chinese New Year.

[I had to take liberties translating 春运.]

This year my family and I will spend Chinese New Year in Japan (again). At first I felt uncomfortable with this. You hear Chinese people say all the time, “Christmas is like you guys’ Chinese New Year,” and while that’s not really true in many ways, it is true in that they both are the year’s biggest holiday in their respective cultures, they both mean a lot to the people of that culture, and they’re both meant to be spent with family. But then how could my wife be OK with running off to Japan (without her parents) instead of spending CNY in Shanghai with them? I would not be OK with blowing off Christmas in similar fashion.

One of the ways I’ve made sense of this cultural issue is reflected in the post above: the Shanghainese really do have a bit of a different take on Chinese New Year, and it has evolved rapidly in recent years (as evidenced by the role of WeChat in the original post). The Shanghainese are different.

My first Chinese New Year was spent in Zhuji (诸暨), Zhejiang Province. It was cold, it was crowded, it was noisy, it was non-stop eating and card-playing and tea-drinking chatting. It was undoubtedly very Chinese. It was pretty fun for me, but as an outsider, it’s not something I would really want to commit to every year (especially if it’s not with my actual family).

Over the years, I’ve discovered that I’m not a huge fan of Chinese New Year festivities. But as the traditions have faded in Shanghai and the holiday is left something of a husk of its former self, I can’t help but feel bad for the Shanghainese.

09

Jan 2020Happy New… uhh… Year?

A reader shared this image with me:

Can you read the Chinese? It’s supposed to say 新年快乐.

I can get the 新年 easily, and then I can make out the 快, but the 乐… the top sort of works, but the bottom just… huh??

It’s fun to see stylizations that don’t work sometimes, too.

P.S. The “translation” I used for the title of this post is sort of a translation of the hard-to-read Chinese. It doesn’t totally work, though, because the “year” part of the Chinese is easy to read; it’s the “happy” part that isn’t. But I didn’t like the sound of “Something New Year,” so here we are! Anyone got a better idea for a translation?

31

Dec 2019New RMB Coins in 2019

I think it really says something that it wasn’t until the last week of 2019 that I even noticed that there are new 1-RMB coins in circulation (I knew about the bills).

What does it say? Well, with mobile payments becoming the new norm in China (at least in big cities), a lot of us just don’t handle much cash anymore (especially coins).

My family just recently visited me in Shanghai, and it was rather surprising for them how “cash-less” meant “mobile payments only,” and foreign credit cards remained largely unusable. The easiest way to get money, by far, was to withdraw RMB in cash from ATMs using American debit cards. (Adding a foreign credit card to AliPay is still early and somewhat unverified.)

What I don’t understand about these RMB coins, though, is the size. Why make them smaller?? It seems like it’s more trouble than it’s worth. I guess it saves on metal, and with fewer and fewer coins actually being used every day, maybe it’s finally the right time…

26

Dec 2019“Baby Yoda” in Chinese

You’re watching The Mandalorian right? It’s the only thing we Star Wars fans have to be happy about in 2019!

Anyway, the breakout hit of the series is no secret: it’s “Baby Yoda” (not his real name).

The Chinese market is famously unimpressed with the entire Star Wars franchise, but just like everyone else, the Chinese love a cute character. So Baby Yoda’s gotta be popular in China too, right? Wellll… kinda. But anyway, we’re talking about how to say “Baby Yoda” in Chinese.

You might be tempted to go straight for the direct translation. Remembering that generic titles (like 老师) typically come come after the “namey” part of the name, you get “Yoda Baby,” or 尤达婴儿. And this name indeed does appear online (currently 216k hits on Baidu).

The Chinese-ier (and cuter) version of the name uses the slangier 宝宝 for “baby,” though, giving us the more natural translation of: 尤达宝宝 (currently 924k hits on Baidu).

So there you have it!

A few other vocabulary tidbits related to the show:

- 星球大战 (Xīngqiú Dàzhàn) Star Wars

- 曼达洛人 (Màndáluò Rén) The Mandalorian

- 原力 (Yuánlì) the Force

- 尤达 (Yóudá) Yoda

- 尤达宝宝 (Yóudá Bǎobao) Baby Yoda

- 曼达洛人 (Màndáluò rén) Mando

- 波巴·费特 (Bōbā Fèitè) Boba Fett

19

Dec 2019Li Ziqi Deserves the Hype

In the past week or so, I’ve suddenly started hearing a lot about the videos of a girl named Li Ziqi (李子柒). She lives out in rural Sichuan and likes to share videos of herself making stuff from scratch (the traditional Chinese way), which includes amazing cooking videos, but also includes creating other stuff as well.

Perhaps what makes her videos most unique (aside from stunning scenery and interesting content) is how little she talks in her videos. I like that. This is the video I watched that totally hooked me, in which she makes an amazing wool cloak from scratch, starting with just the raw wool:

This one on making soy sauce from scratch (and when I say “from scratch” I mean planting the soy beans yourself) was educational:

Li Ziqi is currently getting a lot of attention on Chinese social media. I discovered her myself through a WeChat post. It’ll be interesting to see where public opinion goes. I’ve already heard numerous cries of both “she’d make the perfect wife” and “she’s a fraud.”

Here’s an interview with her:

Anyway, I still need to watch some more videos. But my opinion thus far is that Li Ziqi makes great videos (equally interesting whether or not you’re interested in learning Chinese) and deserves the hype.

12

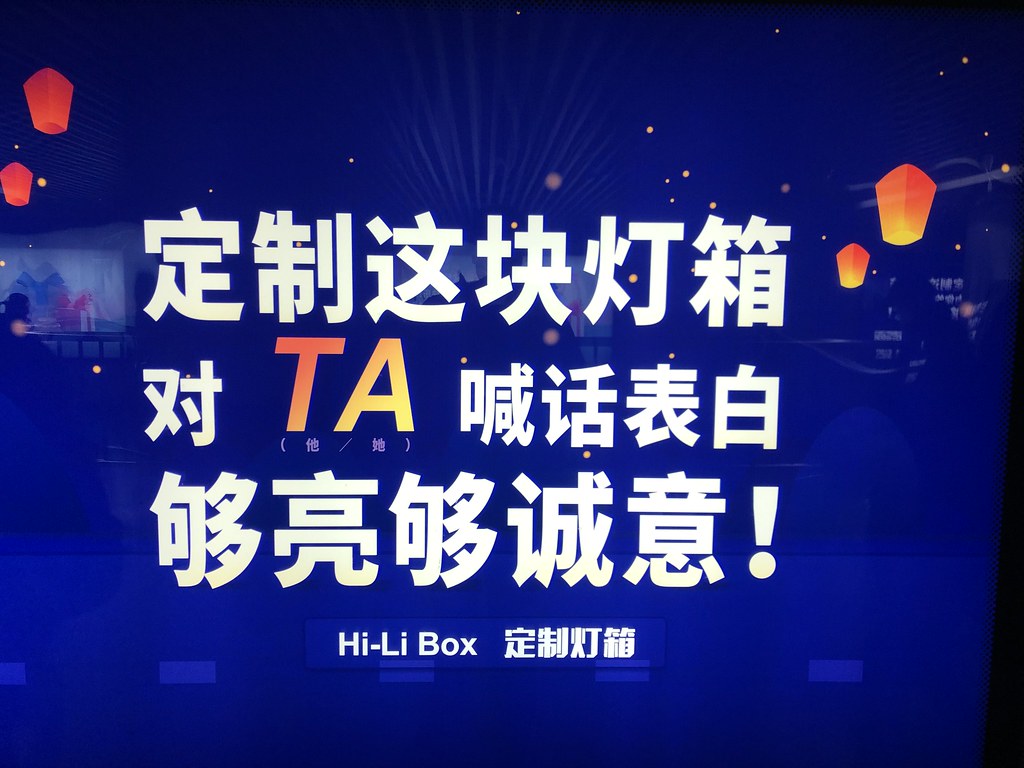

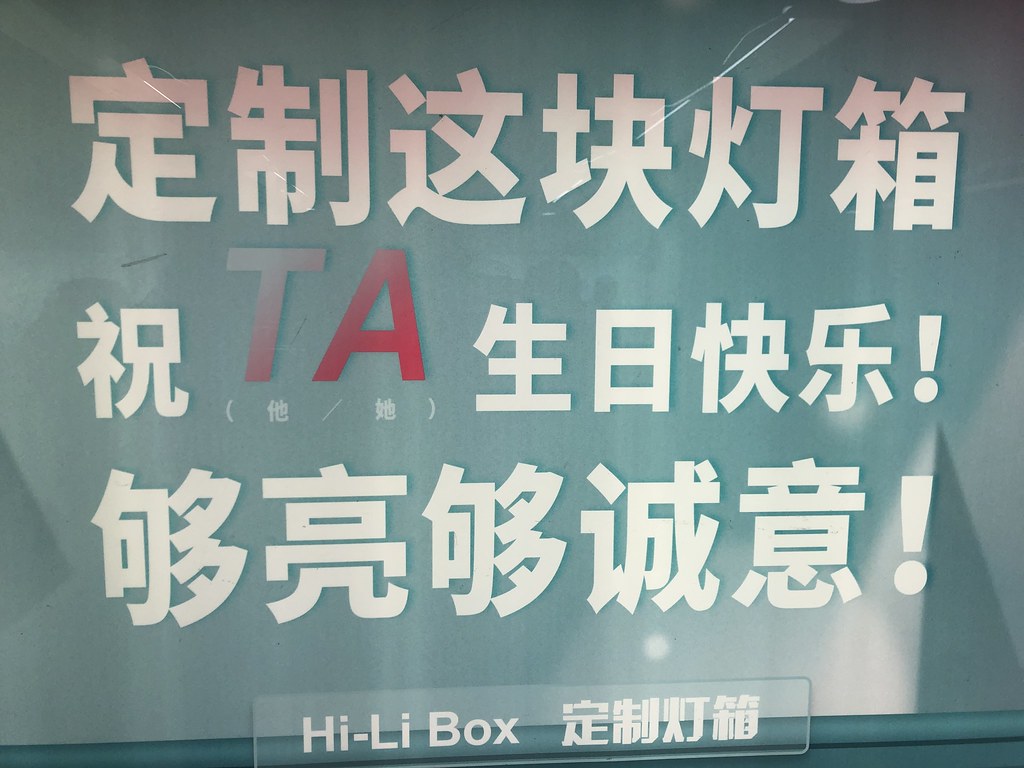

Dec 2019TA: Pinyin with a Purpose

Mastery of pinyin is important for every beginner learner of Mandarin Chinese. This much is widely agreed upon (although not always thoroughly executed). But what about adult native speakers of Chinese? Aside from using pinyin to type, or maybe occasionally to look up an obscure character which they can guess the reading for, there’s not much use for pinyin in their literate lives, right?

Well, you’re mostly right. Pinyin is mostly supplanted by characters among the literate Chinese population. But there is one small exception: TA.

These Shanghai Metro ads are entirely in Chinese except for the “TA.” This phenomenon is fairly common in advertising in China, although these are definitely the best examples I’ve seen because not only are they incredibly clear and highly visible, but they also actually include the meaning of the pinyin “TA” in characters underneath. In case you can’t see clearly, what it says under “TA” is:

( 他 / 她 )

So the point of using “TA” instead of characters is that it leaves the gender unassigned, so that the hypothetical person referred to in the ad can be male or female in the minds of the consumers. I’ve noticed that it is typically written in all caps, as well.

This is, in essence, doing what pinyin does best: providing the sound while leaving the meaning in question. This is something that Chinese characters are often not especially well-suited for, particularly in this case.

(Ironically, the character 他 was not always a “male pronoun” but it kind of evolved that way, and only in the 20th century. Now to escape that corner 他 has been boxed into, the new generation is turning to pinyin.)

For a more scholarly take, be sure to read Victor Mair’s article on Language Log: The degendering of the third person pronoun in Mandarin (Dr. Mair always gets to these topics first!)

05

Dec 2019Free Chinese Christmas Songs to Spice Up the Holidays

It’s Christmastime again, and time to remind everyone that Sinosplice still has some awesome familiar Christmas songs in Chinese. This year I’m posting a selection of the MP3 files online in streamable format, so be sure you’re viewing the original post on Sinosplice.com if you’d like to play the songs without having to download everything.

All right, here we goooo…

Jingle Bells in Chinese

This is version 1 from the album (Mandarin Chinese):

Jingle Bells in Hakka (Hokkien) Dialect

This song is not part of the album because it is NOT Mandarin Chinese. It’s Hakka. (This one is going to have very limited use for most students; it’s just sort of a novelty for most of us.)

Santa Claus is Coming to Town in Chinese

This one is a kids’ version, version 2, also from the album (Mandarin Chinese):

Santa Claus Is Coming to Town (2)

We Wish You a Merry Christmas in Chinese

This song is especially beginner-friendly for learners of Mandarin Chinese (that chorus!):

Silent Night in Chinese

This one is a Christian classic, of course, version 2 from the album (Mandarin Chinese):

Hark! The Herald Angels Sing in Chinese

Another Christian classic, church choir style (Mandarin Chinese):

Download Christmas Songs (zipfile)

If you want to just grab them all, here you go:

The Sinosplice Chinese Christmas Song Album (~40 MB)

+ Lyrics PDFs (1.2 MB)

Disclaimer: I don’t own the rights to these songs, but no one has minded this form of digital distribution (in the name of education) since 2006, so… Merry Christmas?

MP3 Track Listing

- Jingle Bells

- We Wish You a Merry Christmas

- Santa Claus Is Coming to Town

- Silent Night

- The First Noel

- Hark! The Herald Angels Sing

- What Child Is This

- Joy to the World

- It Came Upon a Midnight Clear

- Jingle Bells

- Santa Claus Is Coming to Town

- Silent Night

- Joy to the World

Merry Christmas everybody… 圣诞快乐!

2023 UPDATE:

While we’re on the subject of Christmas and Chinese, AllSet Learning (my company) is doing a special offer with our 1-on-1 online Chinese classes. 3 lessons (one hour each) is a great quantity to try it out or gift to a loved one!