10

Oct 2017QR Code Parking Is Pretty Cool

This parking payment system is in place under Sinan Mansions (思南公馆) in Shanghai:

Basically, your license plate gets scanned on the way in, and on the way out you just scan the QR code, input your license plate number, and pay with WeChat or AliPay. The gate opens automatically on your way out.

You have to remember to scan the QR code, but these are posted all around the parking garage, and it’s way more convenient then finding a little cashier’s office or paying at a booth at the gate.

This same parking garage has “eCars” for rent.

25

Sep 2017Australia Revisited

I first visited Australia in June 2003. I traveled with my friend Wilson, who was also my co-worker at ZUCC in Hangzhou. I remember it was tough saving up for that trip on my meager English teaching salary, and while we had enough funds to visit Brisbane, Gold Coast, Byron Bay, and Cairns, we didn’t have enough to go scuba diving on the Great Barrier Reef. We had enough to go snorkeling, though, and I’m sure glad we did, because it was a once-in-a-lifetime experience that is vanishing (or at least drastically changing) as the reef bleaches.

Here’s a shot from that trip:

Now I’m returning to Australia, 14 years later, with my wife and two kids. I can’t wait for my kids to experience this:

One thing I’ve noticed, living in Shanghai, is that there are an unusually large number of Australians in China that hail from Brisbane. (They’re like the Wenzhounese of Australia!) Now I’ve got a decent number of friends in the Brisbane area, including Matt S, Matt C, Ben J, and Fr. Warren. Although we’re not there yet, what I’ve seen of Aussie hospitality is quite impressive already.

As we approach China’s National Day (国庆节) holiday, it can be difficult to find a decent vacation spot that isn’t absolutely flooded with Chinese tourists. Forget anywhere cool in China; it’s mobbed. Forget convenient international destinations (Thailand, Japan); also mobbed. As far away as Australia is, certain areas of Australia will also be mobbed, so we’ll be having a relaxing time in slightly lower-profile Brisbane.

Anyway, happy birthday, PRC. I’m off to Australia…

05

Sep 2017What is “Tea Pi”?

I’m used to seeing English words mixed in with Chinese advertising copy, and even product names, but this name took me by surprise:

“茶π“?! Why in the world…?

I showed this to some Chinese friends, asking them why anyone would put π in the name of a bottled tea drink. No one had an answer.

I speculated that maybe the “π” was being used as a pun on 派, meaning “faction” or “clique”? They didn’t really like that theory, but they had nothing better to offer.

In my foolish optimism, I searched online for the answer, and discovered it in this article:

你问什么是茶π?

农夫山泉官方表示:果味和茶味的结合,无限不循环的π,就是我们无限不循环的青春!

这……我竟然无言以对啊!

What is “Tea Pi,” you ask?

Nongfu Spring‘s official answer: a combination of tea and fruit flavors, infinitely unrepeating π, which is also our infinitely unrepeating youth!

Uhhh… there’s nothing I can say to that!

Translation: kids these days like random stuff.

30

Aug 2017Chinese Word Order and English Word Order: How Similar?

I get a lot of questions from absolute beginners about Chinese word order. “I heard it’s almost the same as English. Is it??”

It’s not an easy question to answer, but the short answer is: “fairly similar for simple sentences.” And what does “fairly similar” mean exactly? Well, I recently made this video to answer that question!

You could almost make a list of sentence patterns, starting with the simple three-word “SVO” sentences (e.g. “I love you”), and see the Chinese and English word order slowly diverge as you add in more and more complexity. That goes a bit beyond the scope of that simple video, though.

TL;DR: similar, but you still need to study it a little!

P.S. IF you’re wondering where I got that awesome t-shirt, it’s from here.

28

Aug 2017How Heartless Are You in Chinese?

Psychologists at the University of Chicago made some intriguing findings relating to how language learners make ethical decisions. The researchers posed a classic ethics dilemma to the non-native speakers: would you push a person to his death to save 5 others from dying?

Studies from around the world suggest that using a foreign language makes people more utilitarian. Speaking a foreign language slows you down and requires that you concentrate to understand. Scientists have hypothesized that the result is a more deliberative frame of mind that makes the utilitarian benefit of saving five lives outweigh the aversion to pushing a man to his death.

Super interesting! (And fortunately most of us are not learning foreign languages to be placed in roles where we preside over innocent citizens’ lives.)

This immediately made me think of the classroom language teacher who might frequently do foreign language discussions on ethical issues. One could do this for years, thinking all of your students were heartless bastards and the world is doomed, without even realizing this effect was at play. Theoretically.

Anyway, check out the full article on the study.

23

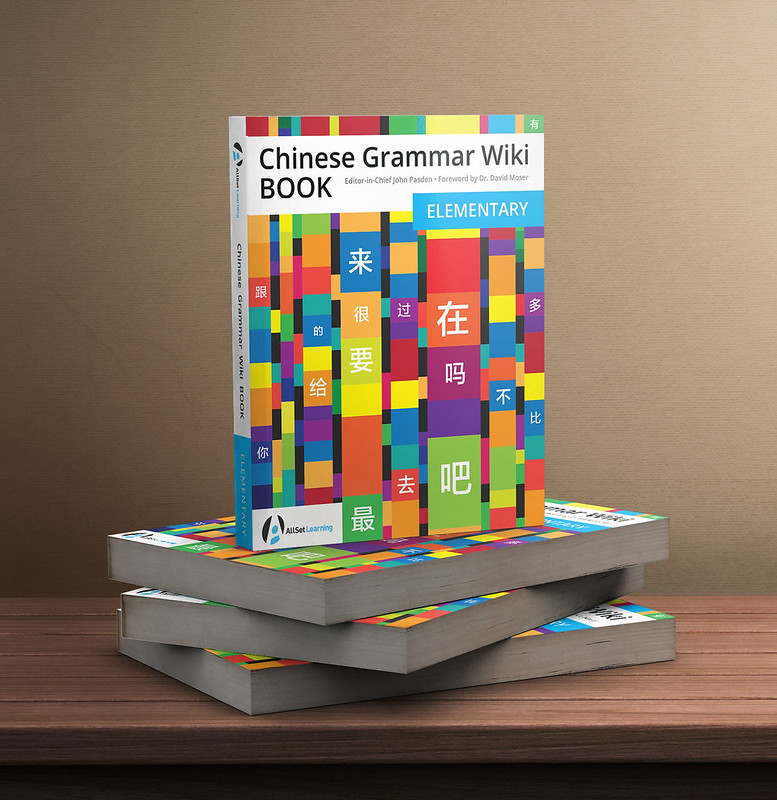

Aug 2017Chinese Grammar Wiki: it’s a print book now!

It’s hard to believe I’ve been working on converting the Chinese Grammar Wiki ebook into a print book for almost a year, but the work is finally done! You can buy the new print version on Amazon. It’s a hefty 2.2 pounds, and has 400 pages. And that’s just beginner and elementary (A1-A2)!

My staff and I were so happy to finally launch the print book that we promptly threw a party over it.

It was going to be a thick book no matter what, so I made sure we didn’t skimp on font size (the Chinese and pinyin fonts are a decent size), line height, or margins. The margins are quite generous. This is a book that you can take some serious notes in, if you are that type of learner.

One of the greatest things about this book, for me, is that the Chinese Grammar Wiki is still there, online and free, continuously updated. Students love it. But for anyone who can afford to support this ongoing project of ours, having an offline version (ebook or print) can be seriously useful.

Special thanks to the always inspiring Dr. David Moser for writing the Foreword, and my tireless content editor Chen Shishuang.

All friends of the Chinese Grammar Wiki: please help spread the word! We’re already working hard on the next book (I’d say it’s 75% done), and we need the support.

17

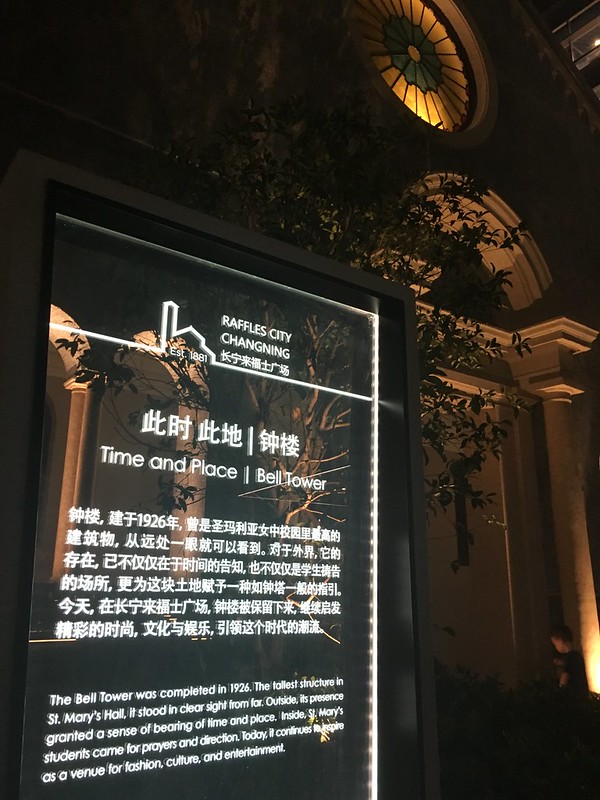

Aug 2017Raffles City Changning Bell Tower

I have always felt that Jing’an Temple (静安寺) in Shanghai was a cool landmark, a gleaming Buddhist temple sitting right in Shanghai’s city center. Sure, it seems to be more of a tourist spot than an actual spiritual center, but the temple definitely imparts a certain flavor to the area.

Now the newly opened Raffles City Changning mall (长宁来福士广场) near Zhongshan Park (yes, right near the other massive mall in Zhongshan Park) has a similar landmark of its own: the Bell Tower. It used to be a church called St. Mary’s. Now it’s… I’m not sure what. (Still looks quite churchy, though.)

Her’s what the plaque reads:

此时 此地 | 钟楼

Time and Place | Bell Tower

钟楼,建于1926年,曾是圣玛利亚女中校园里最高的

建筑物,从远处一眼就可以看到。对于外界,它的

存在,已不仅仅在于时间的告知,也不仅仅是学生祷告

的场所,更为这块土地赋予一种如钟塔一般的指引。

今天,在长宁来福士广场,钟楼被保留下来,继续启发

精彩的时尚,文化与娱乐,引领这个时代的潮流。The Bell Tower was completed in 1926. The tallest structure in St. Mary’s Hall, it stood in clear sight from far. Outside, its presence granted a sense of bearing of time and place. Inside, St. Mary’s students came for prayers and direction. Today, it continues to inspire as a venue for fashion, culture, and entertainment.

15

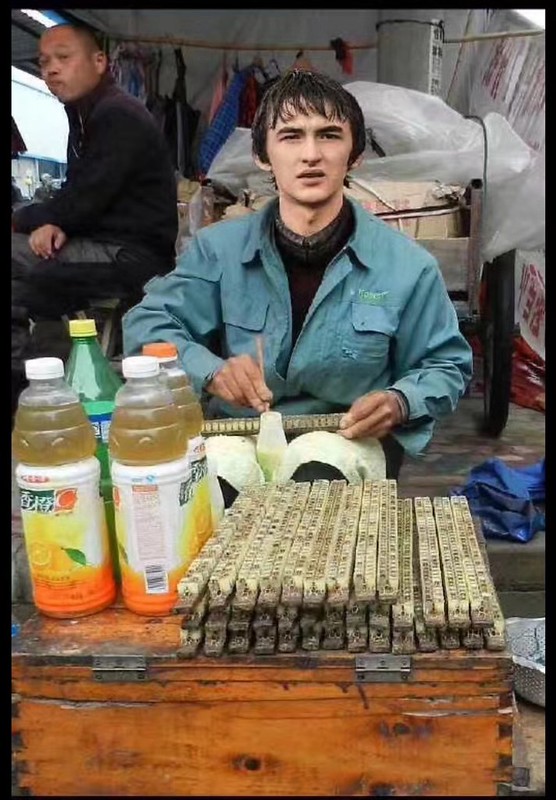

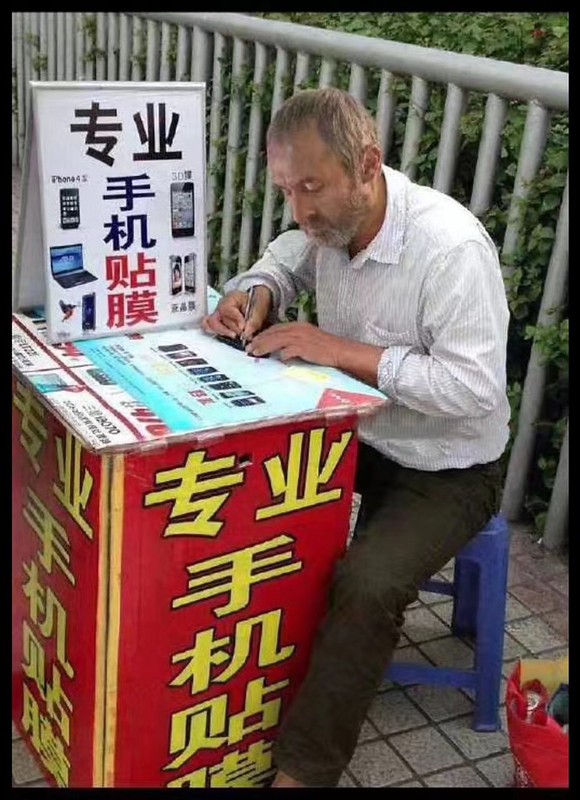

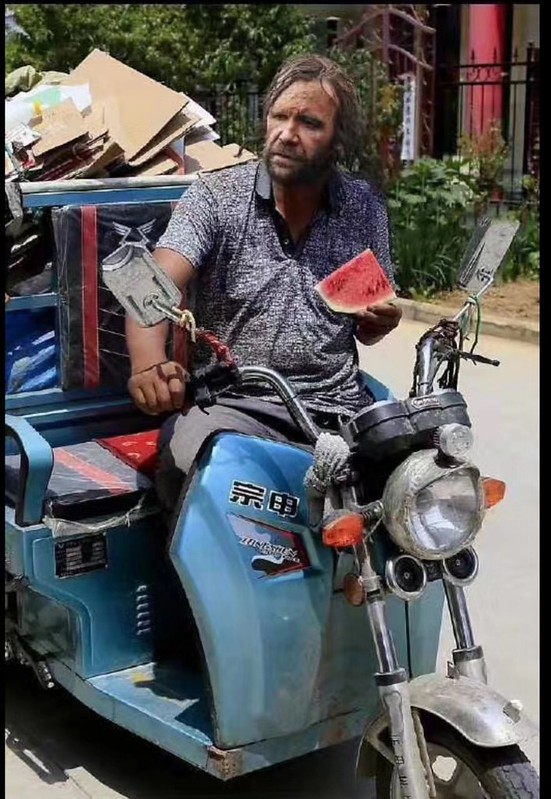

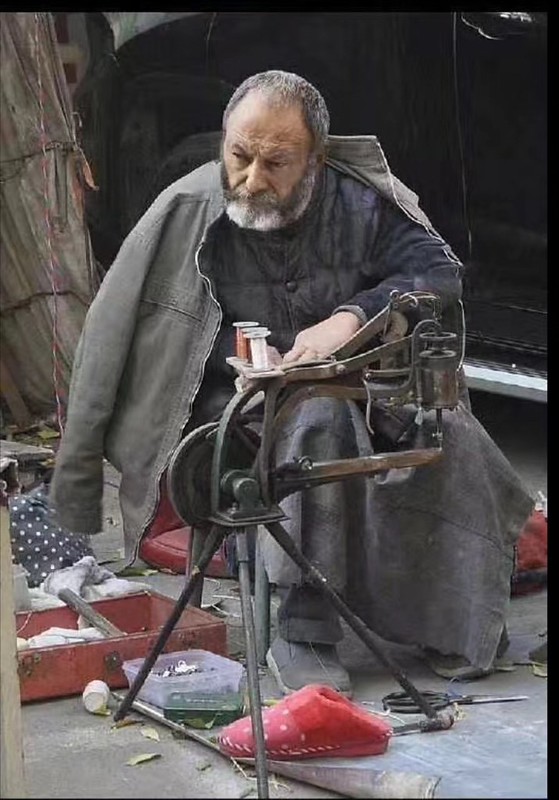

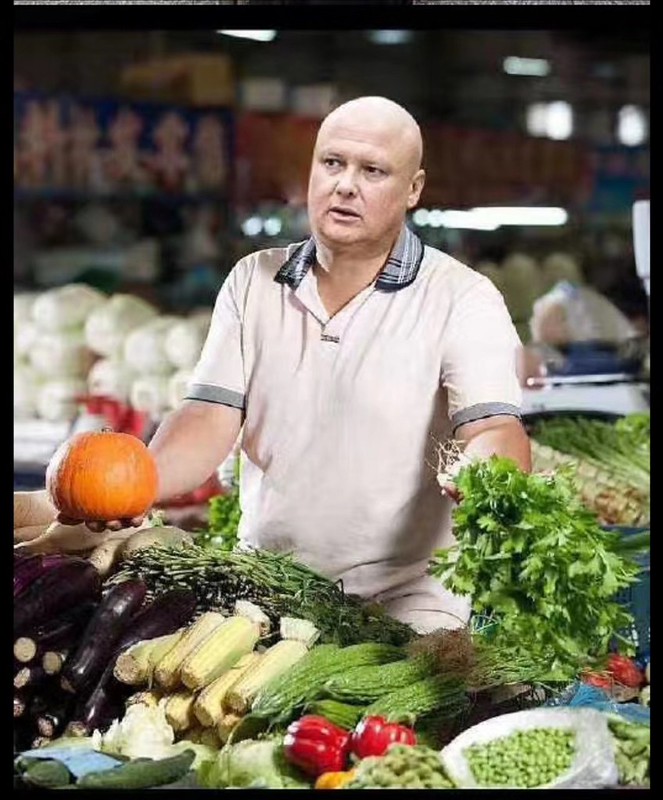

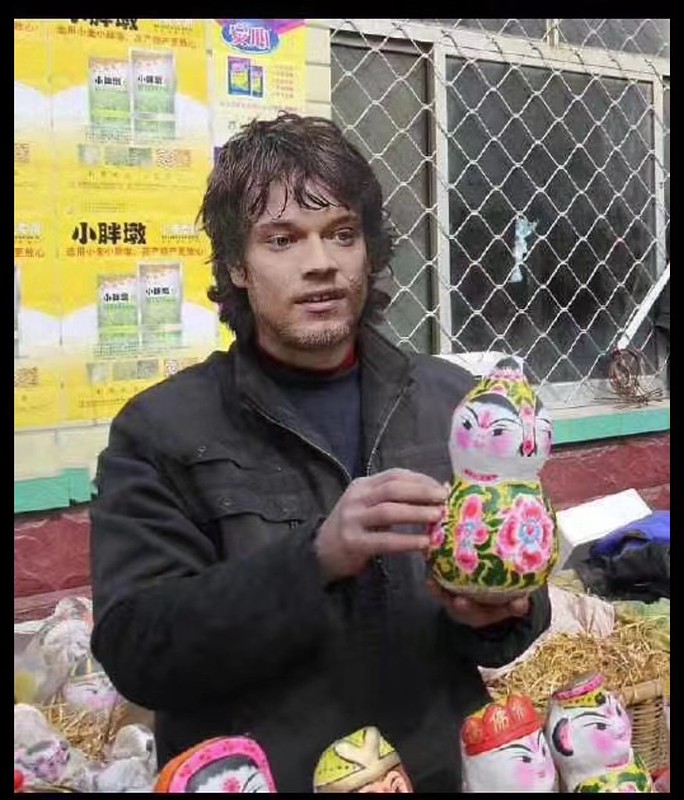

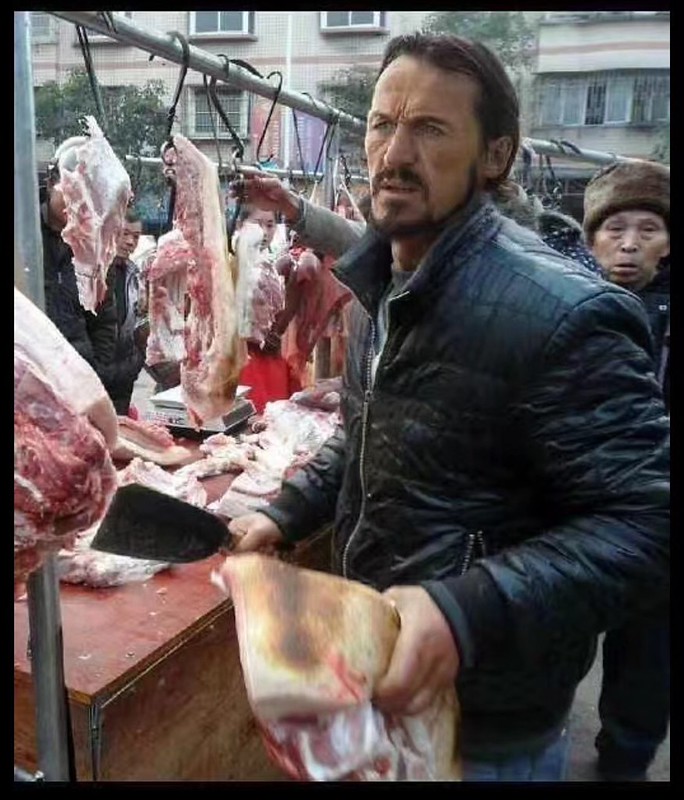

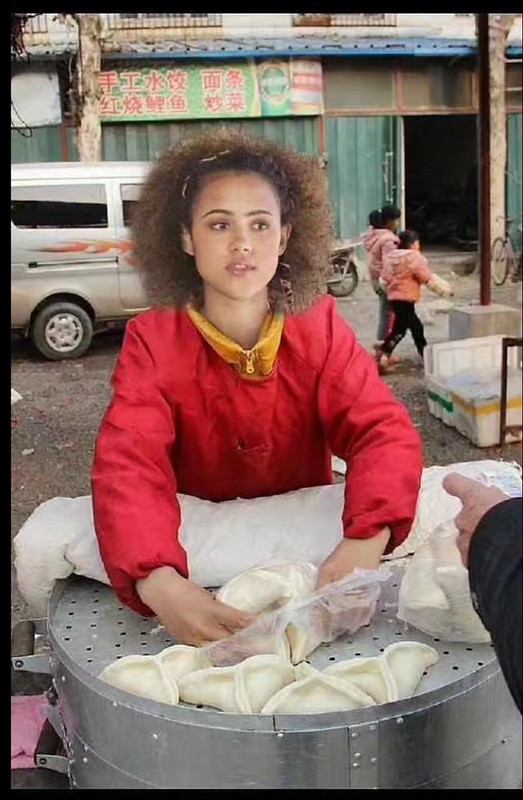

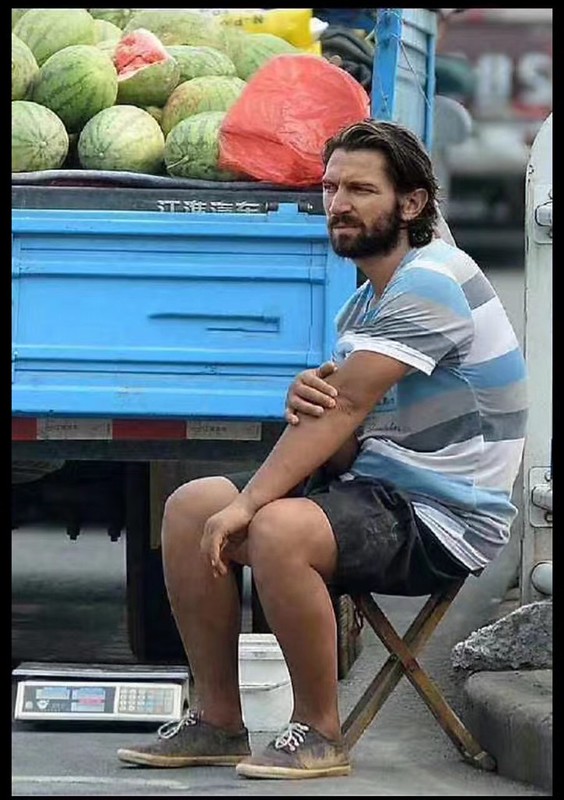

Aug 2017Game of Thrones Characters as Chinese Street Vendors

Saw this Game of Thrones / Chinese culture mash-up gem last night on a Chinese friend’s WeChat “Moments” stream. Too good not to share! Apparently a Chinese Photoshop artist created these, and I’d like credit this person, but I’m still trying to figure out who it is!

Enjoy…

Too bad they’re not high-quality images… it seems they were intended for a smallish smartphone screen.

P.S. If anyone knows the original artist, please let me know, and I’ll credit his/her ASAP!

2017-08-17 Update: The Photoshop artist is Weibo user 青红造了个白. He/she has tons of other similar works. Thanks to Danielle Li and Rachel for the info!

10

Aug 2017Korean BBQ Font Creativity

I found this sign interesting, both for the characterplay with the 南, as well as for the interesting font design (which, unfortunately, also makes it a bit harder for learners to read):

The top reads 江南 (Jiangnan), which is the Chinese equivalent of “Gangnam” (yes, as in “Style”).

The bottom hard-to-read part says 偶巴尔坛, a transliteration of the Korean word “Obaltan” (오발탄), which apparently is the best Korean movie ever made? (I’m a bit out of my depth on this one.) Anyway, don’t feel bad for not knowing what 偶巴尔坛 is as a Chinese learner!

31

Jul 2017The Grammar of an Ode to Stinky Tofu

I never imagined that collaborating with a musician to create a fun song for learning Chinese grammar would result in a love song to stinky tofu (臭豆腐), of all foods! But that is indeed what happened last week. Check out the result, from Chinese Buddy:

It’s a fun song, and there are two kids in my house (and even an adult or two) that can’t stop humming it. From a grammatical perspective, the use of the verb 要 with various objects is highlighted.

My input into the Chinese learning part of the song was:

- Include 要, 不要, and 要不要 as well as a variety of objects

- Try not to let the melody of the song “warp” the tones of the important words too much (especially “yào”)

- Keep the tones as clear as possible, including the tone change for 不要 (bù yào → bú yào)

- Include some “spoken” audio in the song

Yep, four checks! If you’re a beginner working on basic sentence patterns, I hope you find this song helpful. As for the stinky tofu… well, I’ll leave that up to your own judgment.

Do also check out Chinese Buddy on YouTube. There are a bunch of songs (mostly oriented at children), and the styles of the songs range quite a bit, so don’t judge the music on just one or two songs. Probably my second favorite song would the the Tones Song. (Yeah, I have a thing for tones, and also ukulele music, maybe?)

30

Jul 2017Stalled July Posts

July has been a super busy month for me, largely because of all the work that’s gone into getting the forthcoming Chinese Grammar Wiki BOOK out in print form, but also because of a host of other projects, both work-related and personal. So while I can’t say that all of that stuff is done (yet), I can share a little bit about what I’ve been busy with.

I probably would have managed a few more posts in July if not for getting hacked yet again, by some stupid malware script that found an old WordPress plugin exploit. Static site generators are looking more and more attractive…

I joined a gym! And not just any gym, but one that specializes in personal trainer services. It’s not cheap, but I signed up both because I need to get in shape and have been wanting to see what a personal trainer can do, but also because this kind of service is so analogous in so many ways to the personalized Chinese training service that AllSet Learning provides. This experience is offering lots of interesting insights, and I’ll be sharing more on this. (Curious if anyone else has made similar connections between body fitness and language training, on a very personal level?)

My daughter is five and a half, and her English reading is coming along, but now she’s also learning pinyin at the same time. How confusing is that? Turns out, not very. The concept “these same letters make different sounds in Chinese” is not super hard for a kid to get, it seems.

Much to my surprise, I also have a few small video projects in the works. The first one will be shared here very soon.

Everybody needs some down time, right? In between episodes of Game of Thrones, I’ve been immensely enjoying Horizon Zero Dawn. What an amazing game.

06

Jul 2017Conservation Characterplay

This is a sign from the streets of Shanghai:

The original character is 省, which has several meanings, but here is “save” in the sense of “be economical” and “not waste.” Note that in the unmodified original character, the bottom part is 目 and not 口. Wenlin explains 省 like this:

From 少 (shǎo) ‘little’ over 目 (mù) ‘eye’. To 目 watch carefully, to use 少 little, economize.

The drips under the first two in the image are actually characters, which read:

建设节约型社会

Build an economizing society

(I apologize for the poor translation; nothing is coming to mind for a better way to render this in English at the moment!)

27

Jun 20174-Man Harmonica Band Storms Jing’an Park

I’d never seen an all-harmonica band before yesterday, and seeing one turn up in my own neck of the woods in Shanghai (Jing’an Park) was a special treat.

Yep, they had the appropriate performing license, and were playing in the park’s “street busker” area.

I wish I could tell you what they were playing, but sadly, it escapes me. Lively kind of “Old Susannah” vibe. (Not Chinese classics!)

Word of the day: 口琴, harmonica.

15

Jun 2017Kevin Durant Slam Dunks a Bowl of Noodles

I’ve been noticing this mural at a noodle restaurant in Shanghai for several years at least, I think. But the Warriors’ most recent win and Kevin Durant’s performance in particular make me think I should share this odd bit of wall art:

07

Jun 2017Brendan on the Meaninglessness of Chinese Characters

I’ve been dealing a lot with clients’ Chinese character issues, and happened to stumble upon this Quora answer of Brendan O’Kane’s to a question about the origin of the character 奶:

Chinese speakers believe a lot of things about their own writing system, many of them untrue. One of the deepest-rooted and most pernicious of these false beliefs is the notion that characters have meaning. They don’t. The Chinese language [simplifying here; feel free to replace with “Chinese languages,” if you prefer] was spoken long before it was ever written, and has been spoken fluently throughout its history by far more people than have been able to write it fluently. The modern components of a character are not a reliable guide to either the meaning of the character or the early forms of a character, and the characters that make up a word are not necessarily a reliable guide to the meaning of the word. A lot of the stuff referred to as “etymology” in Chinese would more accurately be described as “stories about pictures” — cute, and occasionally helpful for memorization, and sometimes even sort of accurate, but mostly no more truthful than the old story about the English word “sincere” coming from Latin “sine cera,” “without wax,” or about “history” being “his story.”

Lots of interesting ideas here, and Brendan is spot on. And although “Chinese speakers believe a lot of things about their own writing system, many of them untrue,” that doesn’t mean you shouldn’t learn much of what Chinese speakers believe about their language (and writing system). In fact, you kind of have to. That’s culture. It’s like learning about all the ways that “America” is “the land of the free,” even if you don’t believe that the U.S. is that great bastion of liberty. What a people believes about its country is important.

Still, you don’t take everything at face value. Brendan’s point might be a “there is no spoon” moment for you, though, if you’re ready for it.

The key point here is that no bit of language, either spoken or written, has a meaning that people haven’t given it. (For more information on where meaning comes from, read up on semiotics and semantics.) Furthermore, spoken language is primary. Written language is a technology employed by a society. Sure, it’s a special technology with special properties and all kinds of cultural power, but it’s not the language itself, nor is it inherently meaningful in itself. Chinese characters do not hold any meaning that people do not give them.

If all this sounds obvious, that’s great, but if you pay attention, you may notice that Chinese characters do sometimes seem to take on mystical qualities in Chinese culture.

I’m not trying to get overly philosophical or quibble over irrelevant details. The question for me is: what does this mean for the learner of Chinese? Here are a few points:

- You don’t have to know the full origins of every character you learn. Sure, they are sometimes helpful for memorization, and if that’s the case, great.

- It’s worth noting how many non-language-oriented native speakers, fully fluent and literate, have no interest in character origins, and have forgotten most of what they once knew about that stuff. And yet they are still fully fluent and literate in Chinese.

- Since character meanings are neither inherent nor absolute, it’s not bad to sometimes make up your own little stories to help you remember characters. The key is consistency (so as not to confuse yourself), not factual accuracy.

- Still, because characters are such an important part of Chinese culture, it’s not a good idea to make up your own stories that run counter to the standard ones that virtually every Chinese person knows, like the meanings of the most basic pictographic (人, 日, 木, etc.) or the simple or compound ideographic (上, 明, 好, etc.) ones. For the more complicated ones that most native speakers couldn’t explain, your own story mnemonics are safe to use.

This is a complicated issue with tons of cultural baggage, I realize. I’m happy to discuss in the comments!

01

Jun 2017Hey What?

I saw this tea place in the Jing’an area and felt like “Hey Tea” was sort of an odd name:

True, odd English names aren’t so odd in China, I know. But then I realized that this other shop was just around the corner:

Yeah, the original “Hey Jude” pun doesn’t exactly carry over for any random drink.

(More Beatles puns here. This post is for Pete!)

UPDATE: Tom in the comments points out that Hey Tea is a big chain from Guangdong, so it looks like my theory is off.

24

May 2017The Challenge of Implied Grammar Structures

I remember struggling with the unspoken “ifs” of the Chinese language. Sometimes what’s said is meant to be understood as a hypothetical, but there’s no “if” word to be found. You just have to get used to it, and it can be quite bewildering at first.

It was somewhat gratifying, then, to see my daughter struggling just a little bit with this same issue. She’s five and a half now, and fully fluent in Chinese for her age, but she’s still in the process of acquiring Chinese grammar. (See my previous post on grammar points learned by age 2.)

The context was that my daughter had done an especially good job of getting up early and getting ready for school quickly. The conversation with her mom went something like this:

Mom: 你每天都这样就好了!

5yo: 你这是反话!

You could translate the exchange like this:

Mom: If only you did this every day!

5yo: You’re being sarcastic!

This translation into English totally fails to reveal the source of the misunderstanding because I had to add in the unspoken “if,” absent from the Chinese original. The full sentence including the 如果 “if” would would have been:

Mom: 如果你每天都这样就好了!

Because my daughter didn’t understand that there was an unspoken “if” in the sentence, she assumed her mom was being sarcastic, since she was quite clear on the fact that she doesn’t always do a good job of getting ready for school quickly.

In actuality, the 就好了 part of the sentence wouldn’t really make sense without a 如果, so there’s essentially only one possible interpretation of the original sentence. It takes kids a while to figure out the intricacies of these grammar patterns, though!

10

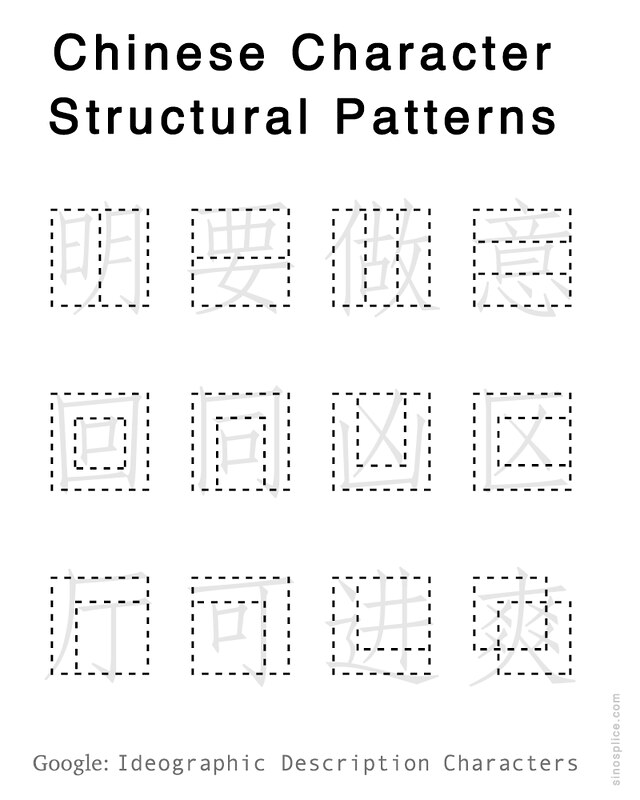

May 2017Learn the Structural Patterns of Chinese Characters

It’s hard to succinctly explain what I mean by this title, because “character structure” and “character composition” are pretty much always used to mean “the character components that make up a character” (or, to use the more outdated term, “radicals”). But the character components would be the content. The limited number of spatial configurations in which those components routinely combine are the “character structure patterns” I’m talking about in this post.

Take a look at this:

If that’s not clear enough, let me break it down for you.

First of all, these “structural patterns” of Chinese characters are referred to as “Ideographic Description Characters” in the IT world, and each one actually has its own Unicode character! So you can copy and paste them just like other text (provided you have Unicode support), and even Google them. (Pro tip: Baidu them. Baidu Baike (Baidu’s Wikipedia) has lots of examples of each type.)

Here are those 12 Unicode characters:

⿰, ⿱, ⿲, ⿳, ⿴, ⿵, ⿶, ⿷, ⿸, ⿹, ⿺, ⿻

The patterns ⿰ and ⿱ (and sometimes a combination of those two, one embedded in the other) make up the most characters. Here are some simple examples of characters that use the more common structural patterns:

- ⿰: 明、昨、休、没、给

- ⿱: 名、要、想

- ⿲: 做

- ⿴: 四、国、回、困、田

- ⿵: 同、网、向

- ⿸: 广、病

- ⿺: 进、运、远、近

My advice is:

- If you’re learning characters, learn these patterns. There aren’t that many, and they’re useful. It’s also good to dispel the notion that character components can be combined in an infinite number of ways. It’s a lot to absorb, for sure, but it’s not an infinite number of options you’re dealing with.

- If you’re teaching characters, teach these patterns (or at least point them out) as you teach the character components. Everyone teaches components, but it’s nice to add a little structure to the teaching of structure. Confirm the growing, amorphous familiarity your students are acquiring, and give it a definite form.

- If you’re building a website or app, include these patterns. It’s not going to be useful to look up characters in this way, but if done right, it could be a great way to explore a character set, and self-directed exploration is one of the best ways to learn.

03

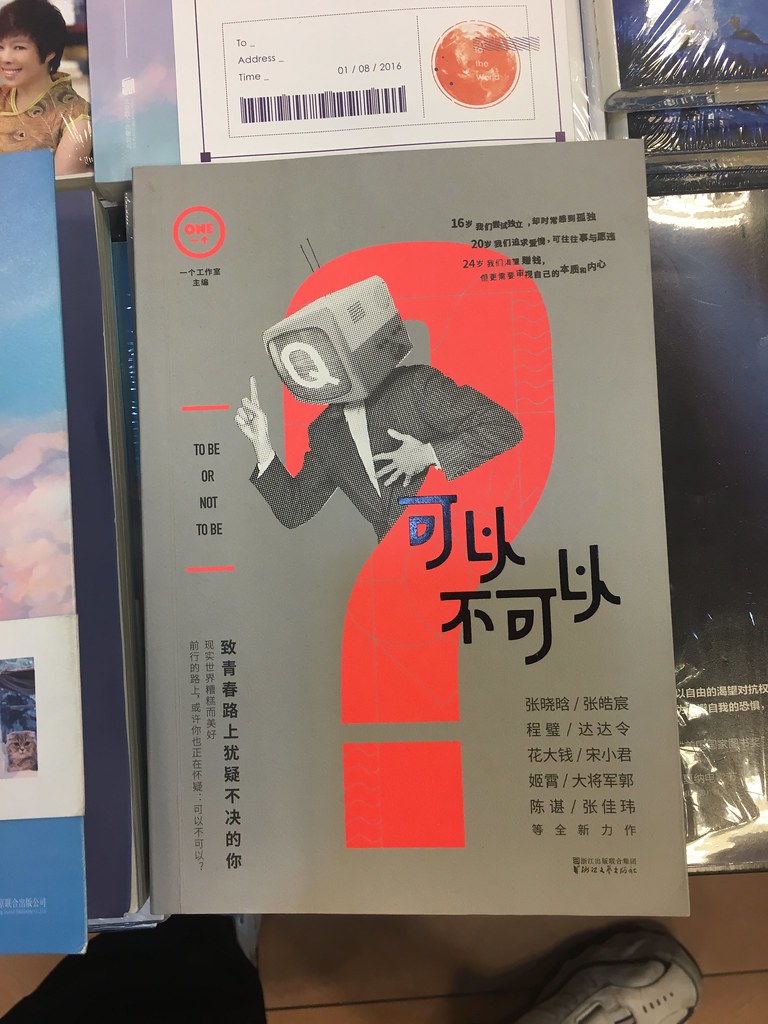

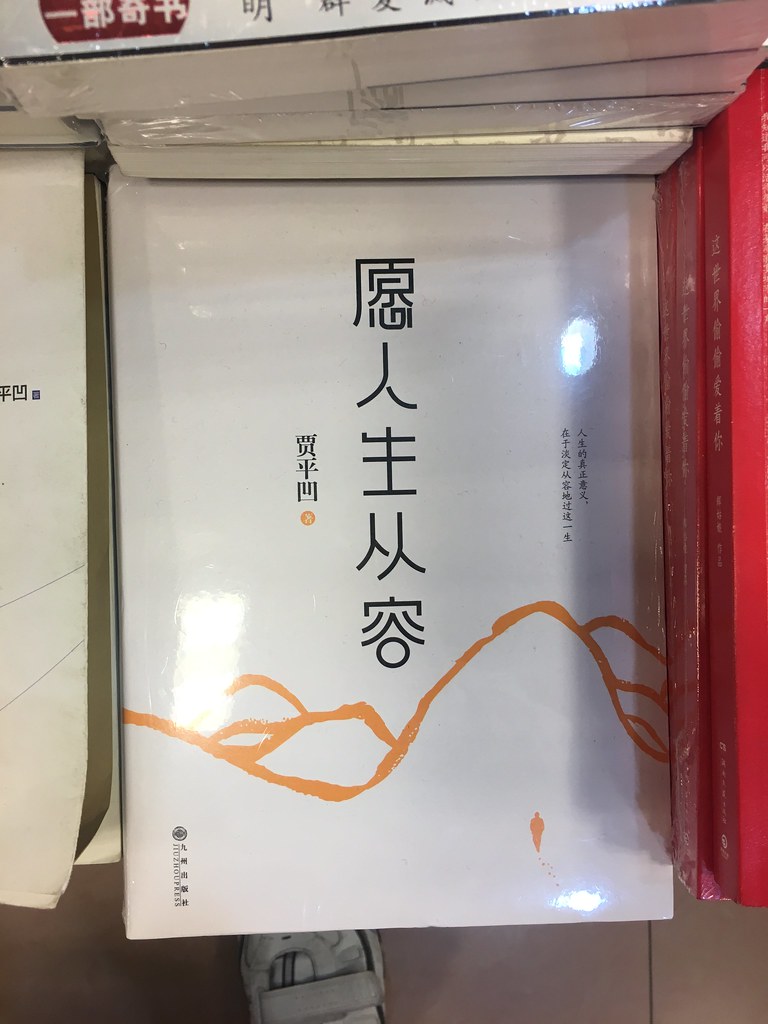

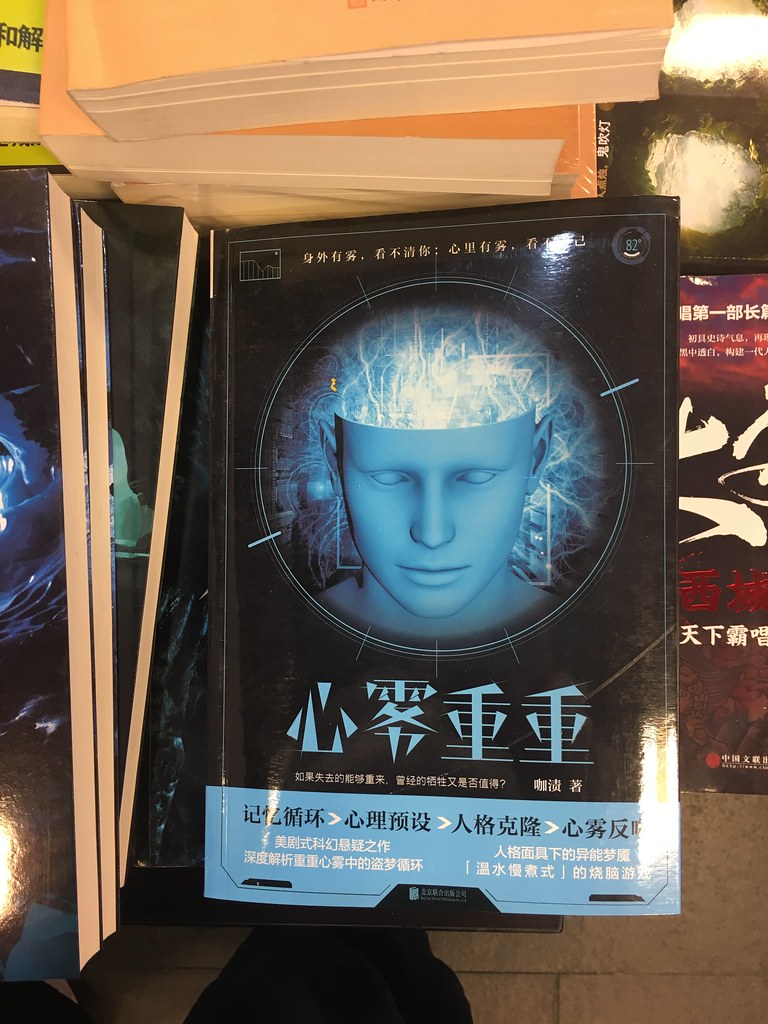

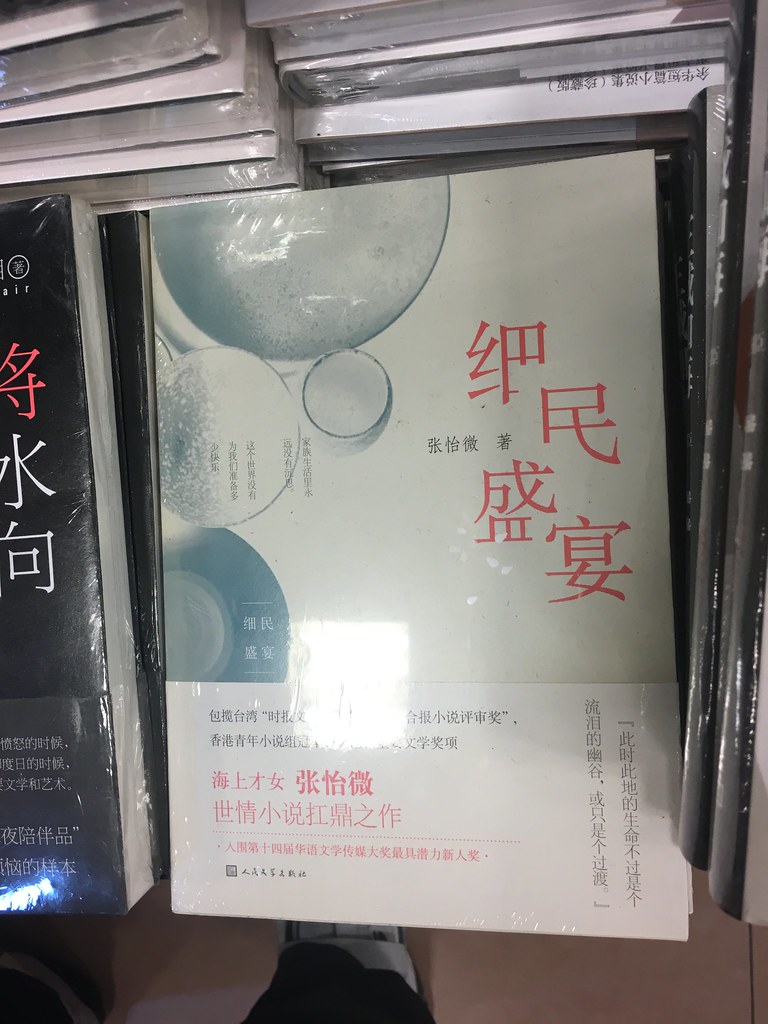

May 2017Cool Custom Fonts for Chinese Book Covers

It’s a lot of work to create a new font in Chinese. Instead of English’s 26 capital letters, 26 lower-case letters, 10 numbers and a smattering of symbols, you have literally thousands of Chinese characters you need for even a basic font. But if you just need a special font for a logo or a book cover, it makes sense to put the design work into just the Chinese characters you need. And if you look at enough Chinese book covers, you discover some cool custom fonts!

Here are some covers with custom Chinese fonts which I discovered on a recent trip to the book store (Chinese title in text below each photo):

I suppose it’s possible that not all of these are custom-designed characters (they might just be fonts I’m not aware of), but they’re still pretty cool!

25

Apr 2017The Cute “Mispronounced” Chinese Words Confounding Your Reading

I recently got this as part of an email from my Chinese bank, China Merchants Bank (CMB / 招商银行):

In case it’s not obvious, for the “cute” fangyan (方言) flavor, the normal word 那么 has been substituted with 辣么 (a non-word). The tone stays the same, but the “n” sound is swapped for an “l” sound, which is common in some fangyan/regional accents, such as the Hunan or Fujian accent.

This has been a trend lately, and you see it a lot, both on Chinese friends’ WeChat Moments as well as in advertising. Here are some others you might notice:

- 灰常 for 非常

- 童鞋 for 同学

- 盆友 for 朋友

- 先森 for 先生

- 菇凉 for 姑娘

- 歪果仁 for 外国人 (appropriately enough, this one intentionally butchers most of the original tones)

- 蓝瘦香菇 for 难受想哭 (this one was quite the meme for a while)

These types of usages are frequently lumped together with other forms of “netspeak” (网络语), but they do share the special feature of swapping a character (or two) to mimic a regional accent. (Have I missed any super common ones?)

These can be especially annoying for learners, because a lot of dictionaries don’t list these slangy words. It’s a great feeling when you start identifying them on your own, but to get to that point, you’re probably going to need to have more than a few conversations with speakers of non-standard Mandarin. The ad at the top of this article just goes to show that even if you try to be elitist and keep your ears “pure” with nothing but 100% standard Mandarin, the non-standard stuff will leak in through the intertubes…

![[Locomotive 1151, Texas & Pacific Railway Company]](https://farm9.staticflickr.com/8562/16269817201_8a737f5d55_c.jpg)