18

Apr 2017Going “Gaga” In Ads

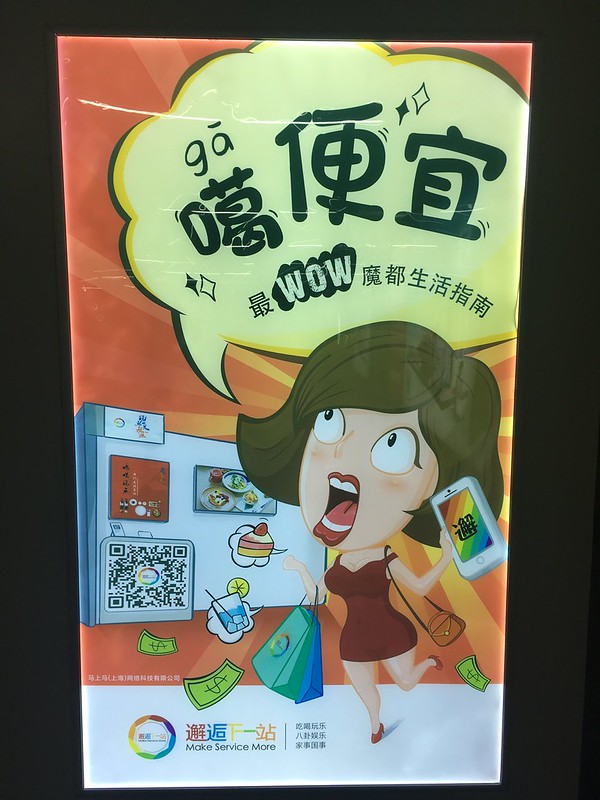

There’s a word 嘎 (“ga”) in Shanghainese (and other Wu fangyan) that just means “really” or “very.” Because it’s not standard Mandarin, you don’t see it written a whole lot, but I noticed it in two different ads in Shanghai recently (and one even has pinyin!):

噶便宜 – really cheap

Also, extra points for:

最WOW – “WOW-est”

嘎实惠 – really a good deal

(And yes, if you want to try using this adverb, you are quite likely to amuse your Chinese friends.)

UPDATE: Commenter Lin and reader Danny point out something I glossed over in the original post: the first ad uses the character 噶, and the second ad uses 嘎. Both are “gā” in this context. So what’s the difference? Well, the short answer is that since this is not a standard word (both characters can be found in the authoritative 现代汉语词典 dictionary, but neither list this meaning), there is no “officially correct” character for it. In my experience, however, 嘎 is more widely used, and it’s also the one my computer’s pinyin input prompts first.

11

Apr 2017Xiamen (take 2)

I don’t write about places I visit much these days… I’m a grumpy old man now, and it’s all “been there, done that!” I feel that Xiamen is worth a special mention, though. I’ve now been there twice, and I really enjoyed it both times, especially the small island called Gulangyu (鼓浪屿).

The reasons I like Gulangyu are not really typical ones, though. First a few pictures, then the explanation…

2016

2017

Thoughts on Gulangyu

OK, first let me get a few things out of the way… I’m not a big fan of Chinese seafood (we have a bad history), and I don’t find any of the food on Gulangyu particularly good. So reasons for liking Gulangyu have nothing to do with food.

The main reasons:

- The island is just fun to explore… Lots of little twisting roads, interesting architecture, tunnels, beaches, little mountains. It’s a fun place. (Reminds me a little bit of Lijiang in this way, but obviously it’s a very different setting.)

- The place is pretty packed with tourists during the day (all clamoring to sample not-great seafood), but at night the place has a special charm. It’s fun to walk around after dark. The roads are well-lit, and surveillance cameras are everywhere (it’s a little disconcerting, honestly), so the place feels quite safe.

- No cars are allowed on the island, nor are scooters. You barely see any bicycles, even. Honestly, this might be a huge part of why I like the place so much… it’s hard to say how much this influences my feelings.

- The weather is great. The first time I went around Chinese New Year in 2016, and I just went again around the beginning of April this year. Very comfy (unlike Shanghai in winter and early spring).

- Lots of little independent shops and restaurants. No Starbucks on Gulangyu. Yes, there is a McDonalds and a KFC,

but there aren’t so many chains, compared to some places, and the little hotels, teahouses, cafes, and restuarants all feel quite distinct (shout out to “Jia Nan D Lounge” (迦南D Lounge)… cool bar, and super friendly staff!).

So, Gulangyu in Xiamen: worth a leisurely visit, in my humble opinion.

31

Mar 2017Germs in China: Immunity Training Ground?

I got through this winter without getting sick (not more than a few sniffles, anyway), UNTIL two weeks ago, when spring arrived and I got hit by a horrible cough, condemning me to long coughing fits every morning and evening for over two weeks. It was the kind of cough that I thought was “getting better” every day, until evening hit. It was bad, but not bad enough that made me go see a doctor. And it’s now finally almost faded away, about 15 days since it started. (You’ll notice I haven’t been blogging for this same time period.)

But this got me thinking about my own immune system in relation to China. After 16.6 years in China, has my immune system been “trained” at all? I don’t think there’s any way to definitively answer this question, but I’ve got a few thoughts, and I’m hoping others might share their experiences.

Growing up in Florida, I was a pretty healthy kid, especially once I got into my teens. My mom was fond of saying, “you rarely get sick, but when you get sick, you get really sick.” I barely remember getting sick at all in college, including the year I studied in Japan. After that I came to China.

My first year in Hangzhou, I had the obligatory newbie food poisoning incident and it was really bad, which ended with me getting an IV in a hospital (as so many illnesses in China tend to). And then as time went on, I would get colds more frequently in China than I had before. I still get hit by the “China germs sucker punch.”

I would expect, after moving to a new environment with a fairly dense population, swimming with a whole new world of germs, to get sick a bit more often than before. And I think this is what has happened, leading up to gradual new “China immunity” layer in my body’s defenses. And over a decade later, I feel that I do get fewer colds, provided that I don’t get too behind on my sleep. But I don’t feel at all confident anymore saying things like “I rarely get sick” now that I live in China.

All this leads me to a few questions I’ve been thinking about:

- Do most expats from the USA (or other relatively sparsely populated western countries) get sick more frequently after moving to China?

- Are most long-term expats able to build up a stronger immunity to Chinese germs?

- Does a long stay in China lead to a permanently stronger immune system in other countries?

- Do Chinese immigrants to the USA get sick less often in the USA than they used to in China?

It would be hard to answer these questions through research, and I realize there are quite a few variables involved (I’m no longer in my twenties, for example) but I’m interested in hearing my readers’ anecdotal evidence. So how about it: in your experience, is China an immunity training ground, or does it simply have its way with you until you’ve had enough?

15

Mar 2017JD.com Brings Some Diversity to Spring Advertising

I’m not saying it never happens, but I see black women prominently featured in Chinese ads seldom enough that I notice when it happens. These ads from the Shanghai Metro are by JD.com (京东), which is a Chinese company, not just a foreign company doing business in China.

There’s also one ad with pale (half-?)Asian girl, and one with random perky white dude:

The ads all read:

是你让春天来

That means, “it’s you that made the spring come.” Not the most inspired slogan, but easy for Chinese learners!

07

Mar 2017Recruiting Talent

The character here is 聘 (as in 招聘, referring to “recruiting for a job,” in other words, “now hiring”), with a little 才 thrown in for flavor:

That’s not the adverb 才, but rather the one in the word 人才, referring to “talent.”

P.S. On a related note, my company AllSet Learning is currently looking for new academic interns. You can see what past interns have done here.

02

Mar 2017The English that Feels Weird in Your Chinese

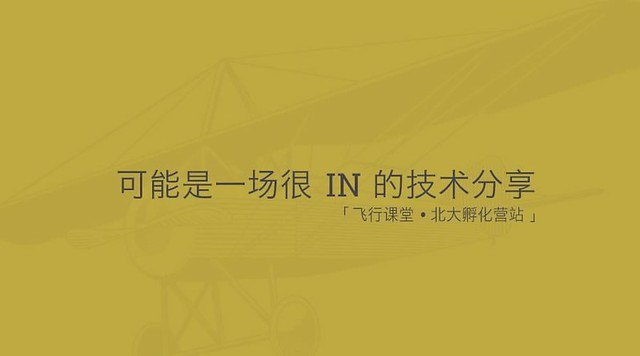

Anyone that has studied Chinese for a while and made it to at least the intermediate level will notice that certain English words are used. Sometimes it’s words that seem cool or trendy to use in English, like “Starbucks” or “Doctor Strange.” Other times it’s English acronyms that are just easy to keep in English rather than translating into Chinese, such as “FBI” or “NBA” or “MBA.” And still other times, it’s “false acronyms” with Chinese characteristics such as “PPT” (for Powerpoint presentations) or “APP” (for “app”).

I’m not talking about any of those. These are all fairly easy to pick up and incorporate into one’s daily conversations. I’m talking about another kind, while not difficult at all to understand, made me cringe a little at first. And now, even though I’m quite used to them, I can’t really stomach using them in my own speech. But these are words that I hear even people that don’t speak much English using.

Some examples!

- make sense: most notably, the phrase “不make sense.” (I recall Jenny used to use this on ChinesePod occasionally, but she’s not the only Chinese person to use this English phrase in Chinese!)

- man: this means “manly,” as in “很man“

- fashion: this means “fashionable,” as in “很fashion“

- in: used as an adjective to describe fads or trends, as in “很in“

- out: used to describe what’s NOT cool, but this time as either an adjective or as a verb: “太out了” or “你out了“

- OK: although sometimes this word feels just like it does in English, there’s something about the phrase “也OK” instead of “也可以” that always feels odd to me

- high (often written as “嗨“): I’ve never heard this used in the “drug high” sense; it’s always in the “natural high” sense, as in “玩得很high” for “have/had a blast”

- get: this seems to be a synonym for 懂, as in “只有你能get我“

- down: a verb, short for “download”

Here are some examples collected from the web. Many of them seem to be from Taiwanese sources.

To be clear, this is not just regular “Chinglish,” where English gets randomly mixed in with Chinese. These are words that seem to have snuck into common usage among young people (maybe first in Taiwan?), even when those people don’t speak much English, and don’t necessarily even have an international education.

Do these usages feel weird coming out of your own mouth? Or can you use them naturally?

What other examples can you share?

28

Feb 2017Terrible Product Name “and” Characterplay

My love of characterplay aside, “and” has to be one of the worst English product names I’ve ever seen. It’s a faithful translation of its Chinese product name, 和 (meaning “and”), but that doesn’t make it any better.

Some shots from the Shanghai Metro:

22

Feb 2017Ofo Rental Bikes Are Getting OWNED

I’ve recently commented on how the sudden rise of app-driven bike rental services in Shanghai is fairly staggering. From a casual look around the downtown area, it’s clear that Mobike and Ofo are currently the top dogs, and Ofo seems to be doing all right with its “cheaper” business model, despite its late entrance to the market. But I’ve recently learned that Ofo’s service has some pretty glaring flaws when compared to Mobike.

How Mobike and Ofo Differ

Both services use apps, but Mobike’s bicycles are more high-tech, and that makes a big difference. Mobike bikes have tracking devices embedded, and the bike locks are unlocked remotely through the network. Ofo bikes use simple combination locks that you can request the code for through the app.

So the Mobike service works like this:

- Use the app to find bikes near you

- Unlock a particular bike by scanning its QR code with the app

- (The bike’s lock automatically unlocks after a few seconds)

- Use the bike

- Park the bike and manually lock it

- Mobike’s services are informed the ride is over, and the bike’s location is made available to other users through the app

…and the Ofo service works like this:

- Find a bike yourself (no tracking devices)

- Send the bike’s ID number to Ofo via the app

- Receive the combination to the mechanical lock

- Unlock the bike with the combination

- Use the bike

- Park the bike and manually lock it

(Note: I don’t use Ofo myself, but I’ve spoken with people who do. Ofo bikes also have QR codes on their bikes, but they’re for the purpose of advertising the app, not unlocking the bikes. The Mobike QR codes serve both purposes.)

It seems like the Ofo system is fairly straightforward and would save a lot of money, right? Oh, but it has problems…

Ofo’s Locking Problem

Because Ofo uses combination locks, none of the bike locks are truly locked unless the last user changed the combination after closing the lock. And, it turns out, a lot of people don’t. A good number of Ofo bikes on the street are actually unlocked, if you just press the button on the lock.

When I first heard this, I was skeptical, but the very first bike I tried was unlocked. Later, I checked a sample of 20 bikes in the Jing’an area, and 4 were unlocked. So, 1 in 5. That’s a lot!

As it turns out, this isn’t Ofo’s worst problem, though…

People Are Publicly Stealing Ofo’s Bikes

Ofo bikes are locked with combination locks, and those combinations don’t change. So if you save the combination and can find the same bike again, you can use it for free. The only thing keeping you from using the same bike again is the sheer number of bikes out there and the other people using them. And the way that other people use the bikes is to request the combination through the app. But what if they couldn’t get the combination for “your” bike? To get the combination, other users need to read the bike’s ID number. But if this number is missing or unreadable, no one else can get the combination.

So this is how people are “owning” Ofo bikes. They’re getting the combination to a particular bike, and then scratching off or otherwise removing the bike’s ID number. I did a bit of hunting for “owned” Ofo bikes parked on the street, and did find a few. Logically, though, the “owned” bikes are probably going to be parked in less public places. I really wonder how many Ofo bikes have disappeared off the street.

I also wonder if this aspect of the “cheap bike” strategy has already been taken into account. Ofo has ample funding, after all. How many bikes can Ofo afford to lose and yet still have lower costs than Mobike, with its fancy high-tech bikes? Or, how many Ofo bikes need to be stolen before people realize that it’s easier (and not at all expensive) to just leave the bikes in the system? How long does it take before “owning” a ripped-off Ofo bike is uncool and/or shameful? Hard to say… and there are a lot of people in Shanghai!

Strange Competitive Practices

The other day near Jing’an Temple I snapped this shot of a few guys slowly escorting a “cargo tricycle” full of Mobike bicycles. The strange thing was the two of them were riding Ofo bikes!

I was in a hurry, so I didn’t even try to ask them any questions, but the guys were wearing clothes which read 特勤, which is probably short for 特殊勤务, something like “special forces” (a division of the police).

At least one Chinese person I showed these pictures to thought the uniforms looked fake, but who knows?

Ofo in Chinese Is “O-F-O”

Just a final note on the Chinese names of these two companies:

- Mobike: 摩拜单车

- Ofo: O-F-O

Yes, Ofo in Chinese is spelled out, just like the word “app” is spelled out in Chinese as “A-P-P.”

16

Feb 2017Subvocalization While Reading Chinese

According to Wikipedia, subvocalization refers to “the internal speech typically made when reading.” It’s that “voice in your head” (you) pronouncing every word mentally. Subvocalization is normal, and is not generally considered a problem, unless you’re trying to learn to speed read. In that case. subvocalization is generally regarded as something that slows a reader down.

I found this section of Wikipedia quite interesting:

Advocates of speed reading generally claim that subvocalization places extra burden on the cognitive resources, thus, slowing the reading down. Speed reading courses often prescribe lengthy practices to eliminate subvocalizing when reading… [but] for competent readers, subvocalizing to some extent even at scanning rates is normal.

Typically, subvocalizing is an inherent part of reading and understanding a word. Micro-muscle tests suggest that full and permanent elimination of subvocalizing is impossible. This may originate in the way people learn to read by associating the sight of words with their spoken sounds…. At the slower reading rates (100-300 words per minute), subvocalizing may improve comprehension.

The Case of Chinese

OK, but now what about for Chinese? Chinese characters are not as directly tied to a phonetic system (like an alphabet), right? Plus Chinese kids learn characters by writing them over and over rather than by reading them aloud, right?

Well, not really. Here’s what research has to say (I added bold to certain parts):

…Reading English and reading Chinese have more in common than has been appreciated when it comes to phonological processes. The text experiments suggest that readers in both systems rely on phonological processes during the comprehension of written text. The lexical experiments show differences just where it is expected: Evidence for early (“prelexical”) phonology in English but not in Chinese, but evidence for still-early (“lexical”) phonology in Chinese. The time course of activation appears to be slightly different in the two cases. Thus, the similarity between Chinese and English readers is shown not in their dependence on a visual route, but in their use of phonology as quickly as allowed by the writing system.

So it’s not that Chinese readers don’t subvocalize; it just kicks in later, because it takes for time for readers to amass the knowledge of written Chinese needed. Interesting!

Obviously, you can dive a lot deeper into the research on subvocalization, reading comprehension, and cognitive differences between writing systems. (Please feel free to share links to relevant studies in the comments.) For my purposes, though, one important point is clear: there’s no need to exoticize reading Chinese any more than necessary. Yes, learning a bunch of characters is a hurdle, but you don’t really need to worry too much beyond that.

Subvocalizing in Chinese

First of all, we should remember that subvocalization is not “bad,” and it’s not something that native Chinese readers don’t do (some kind of “laowai problem”). But that doesn’t mean that there’s no danger of over-reliance on subvocalization when learning to read Chinese.

I personally have experienced what I consider a serious impediment to my reading fluency. I found that when I would read Chinese a text, I was reading it aloud very deliberately in my head (subvocalizing). The problem was that I had obsessed over correct tones for so long that I just couldn’t stop. This slowed me down even more than normal subvocalization would be expected to do. So even when I was just reading for purely informational purposes, my brain was insisting that I had to pronounce every tone of every word (in my head) exactly right. I knew this was slowing me down a lot, but I couldn’t stop! The “tone police” in my head were out of control.

I did eventually get over this bad habit, and the result was much more rapid reading speed, as well as the ability to truly scan a text for meaning quickly. How did I do it?

Two Cures for Subvocalization

My solution was “the firehose.” I forced myself to read a lot. I read long Chinese texts for which I knew the words, but wasn’t sure of the tones for all the words. In some cases, I may not have even been sure of all the exact readings of all the characters in those words. But I could still comprehend the general meaning of the texts, which was all I needed.

So the steps were:

- Find a relatively long text which had information I needed (make the reading meaningful)

- Don’t allow myself to look up words (no popup pinyin plugin allowed!)

- Force myself to read at a high speed, disallowing my brain from obsessing over uncertain readings

This worked, but I had to do it a lot, and to be honest, it was a little painful. Unlearning a habit is not easy, and if I’m not careful, I still find my brain dutifully reading aloud every single tone in my mind. But with just a little willpower, I can keep subvocalization in check when I need to, and greatly increase my reading speed.

The second solution is extensive reading. It’s a gentler version of the method described above. The idea is that if you know that you already know all the words (with correct tones) in a text, then forcing yourself to read it without focusing on the correct tones should be easier. No anxiety. You can let go and just read.

But here’s the key: you can’t just read a text first to identify all the words you don’t know, add the pinyin, and consider them “learned.” That’s not going to allow you to let go of subvocalization for unfamiliar texts. So you need to find reading material which is unfamiliar, and yet entirely composed of familiar words. This is what graded readers can help with.

Share Your Subvocalization Battle Tales

I’d be very interested to hear about any readers’ struggles with subvocalization when learning to read Chinese. Actually, any foreign language… it’s all relevant.

14

Feb 2017Crazy Circus Chinese Characters

I’m always on the lookout for interesting, creative use of Chinese characters, and that includes cool and weird Chinese fonts. Well, the characters at the bottom of this poster really caught me by surprise, because I didn’t even realize they were characters at first:

If you’re struggling to make anything out, note that English at the bottom right: “Crazy Circus City.” Big clue.

OK, here’s what it reads:

疯狂马戏城

Literally, “crazy (疯狂) circus (马戏) city (城).”

(Don’t worry if you still find it hard to read even after you know what it says, and even if you know the characters. It’s really hard to read!)

For some reason the traditional form of 马 is used, though: 馬. My Chinese teacher back in college always told me that mixing simplified and traditional characters was a big no-no. It’s just too… crazy.

If the whole thing had been in traditional characters, it would have read:

瘋狂馬戲城

01

Feb 2017Happy Year of the Rooster

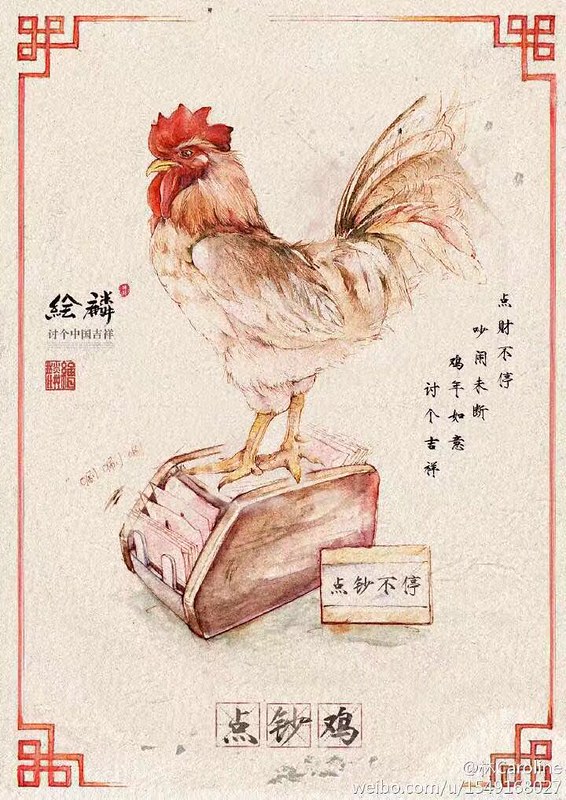

Happy Year of the Rooster/Cock/Chicken! Just as the English word “cock” has multiple meanings, the Chinese word 鸡 (“chicken”) does as well. By itself, it can mean “prostitute,” but the same sound “jī” is also part of the Chinese word for, well, “cock.” I guess I’m friends with a bunch of upstanding Chinese folk, because I didn’t see the many puns I feel I could have for this year’s barrage of Chinese New Year greetings.

Here’s one tame pun I did see this year:

So the original word is 点钞机, “money counting machine.” Substituting 鸡 (“chicken”) for 机 (“machine”) doesn’t change the sound at all, but 点钞鸡 falls right in line with the Chinese proclivity for wishing financial success in the New Year. And you can totally imagine a money counting rooster.

26

Jan 2017Happy New Year Teeth

Chinese New Year is just around the corner, and I bring you this pun/characterplay combo. Unfortunately, neither is particularly clever, but at least it’s not hard to understand!

The large text of the ad reads:

新年好呀

This basically just means “happy New Year,” but the 呀 on the end is a modal particle you hear a lot in Shanghai. It adds a tone of playfulness, possibly childishness.

The pun is on 好牙, which refers to “good teeth.” (The two-character word for “tooth” or “teeth” is 牙齿). And since it’s an ad for dental services, the pun on good teeth is quite appropriate.

But do you see where the 口 component of 呀 (the modal particle) is actually a tooth? That’s the characterplay aspect. But the weird thing is that if you take away the 口, what’s left actually does literally mean “tooth.”

Anyway, 新年好!

24

Jan 2017Shanghai’s Mobike Mania Invites Competition

I noticed at the end of 2016 that Mobike seemed to be really taking off in Shanghai. But when I came back from Florida in January, it was a whole ‘nother story… Not only were there more orange Mobike bikes on the streets than ever, but yellow (Didi-backed) competitor Ofo was suddenly seriously competing, and even baby blue 小鸣单车 was upping its game. I’ve been seeing so many rows of Mobikes on the sidewalks of Jing’an District that I’m guessing there now must be nightly redistribution efforts going on to properly seed the city center. Now that the Uber war is over, this seems to be the new battlefront.

A few shots I snapped last week:

And one photo I downloaded on WeChat (not sure who to credit), which was labeled “#VCfunding“:

18

Jan 2017SmartShanghai Interview

I just recently did an interview with SmartShanghai: [10-Year Club]: John Pasden of Sinosplice and AllSet Learning. It also has a tagline: A trip down memory lane with long-time Shanghai-based language specialist John Pasden. Dude speaks Chinese with the intensity of 1000 exploding Da Shans. That “exploding Da Shans” line cracks me up for many reasons.

Long-time readers of this blog will probably appreciate this answer I gave:

SmSh: I know you get this a lot — speaking specifically to your job, what are some tips for people trying to learn Chinese?

JP: You have to get out of your comfort zone. I know a lot of people that get out of their work “expat bubble” and talk to Chinese friends, but they’re only talking to Chinese people with pretty decent English. Not enough discomfort! Try talking to your ayi about her kids, or ask the fruit stand guy how much he pays for rent, or try to convince the guard in your apartment complex to stop smoking. You may think your Chinese isn’t good enough, but you’re not giving yourself enough credit. Look up a few words or phrases in Pleco, and give it a shot. Those are the conversations that will NOT be comfortable at first. You will likely fail hard at some of them, but those people are not going to switch to English, and they’re likely to have more patience for your bad Chinese than you do. And if they laugh, just assume that it’s because you made their day by even trying to talk to them in Chinese.

The whole interview is on SmartShanghai.

11

Jan 201716 Sincere Answers to 16 Tiresome Questions about Life in China

I recently read an article titled 16 Things Expats in China are Tired of Hearing Back Home. My immediate reaction was: this is so on the money. I have definitely heard all of these. Having just spent 3 weeks in the States, I have very recently heard many of these.

But rather than simply sharing this list, I thought it might be useful to give my sincere answers to these questions, because none of them are really stupid questions. They’re just kind of hard to answer briefly. So I’ll answer, but occasionally take the easy way out by linking to old entries of mine.

So, without further ado, here we go…

1. “So what is China like?”

This is the most common and hardest one to answer. It would be interesting to see a bunch of different long-term expats answer this in 200 words or less. Or maybe in haiku form. Anyway, it’s a tough question because it’s way too broad. But I actually do get why people ask this, and I think the motivation is good, so I’ll attempt to answer (and you can also see what people say on Quora).

The one time I really tried to answer this question was in a blog post I wrote in 2006 called The Chaos Run. In that post, I described “a near-perpetual state of excitement.” This place really is seething with energy.

Obviously, living in China is not all fun and excitement. Expats complain about life here a lot, and don’t tend to stay too long. An apt description of life in China is that these are “interesting times.” Just as the supposed Chinese curse implies that “interesting” is not always positive, neither is life in China. “Interesting” is good food, amazing work opportunities, and great people, but it’s also food safety issues, pervasive pollution, and infuriating social interactions. How much of the good and the bad you end up with depends largely on where you live in China, what you do here, whether you’re here alone or with a family, what you expect to get out of your stay here, and a bunch of other factors. And, of course, there’s the element of luck and the undeniable role of your own attitude about the experience.

But it’s definitely interesting.

2. “Wow, that must have been a really long flight!”

Yeah, I typically fly 13-14 hours just to get to the States from Shanghai, and then another 3-5 hours in the air to get home to Florida. I have learned that flying into California is no good, because I always need two more flights to get to Florida, and adding in the layover time, that will nearly always results in a trip over 24 hours! (It usually takes me 20-22 hours to get home, though.)

3. “Can you speak Chinese?”

Yes. I knew some broken Chinese before even coming over in 2000, but I wasn’t even conversational, really.

And yes, I would say that learning Chinese is hard. But it’s worth it.

4. “So you must be really fluent in Chinese now.”

Fluent enough. You can read about how I learned Chinese here on this website.

I also run a company called AllSet Learning which helps move highly motivated individuals closer to fluency every day.

5. “What made you decide to go to China?”

I wanted to see the world and learn languages while I was young! I kind of got hung up on the first country I stopped in, though, and I’ve been here ever since. No regrets.

6. “I heard the pollution in China is really bad!”

It is very bad. Beijing and other northern cities are way worse than Shanghai, but it’s not great anywhere.

I am personally not bothered by it here in Shanghai on a daily basis. I’m not as sensitive as some people to the pollution, even if I’m breathing in potentially harmful air 24/7. I would not want to live in Beijing, however, mostly for this reason (it’s a very cool city otherwise).

7. “I heard that in China [insert widely reported misconception]. Is that true?”

I don’t really mind questions like this too much, because I frequently hear crazy things this way that I’ve never heard while living in China. And honestly, truth is stranger than fiction. I hear bizarre stories every day about what’s going on in China. (It’s “interesting” here, remember?)

Websites like Shanghaiist cover this aspect of life in China pretty well. If you want more serious China news, check out Sinocism.

8. “Can you use chopsticks?”

Yes.

I hear this question from Chinese people much more than from foreigners. Chinese people who don’t have much contact with foreigners are often surprised to see a foreigners using chopsticks. I usually inform them that it’s pretty easy to learn chopsticks, lots of foreigners can do it, and then I quickly change the subject.

9. “Do they have [insert foreign brand] over there?”

Some of the most common western brands you see everywhere are: Starbucks, KFC, Pizza Hut, McDonalds, Nike, Apple. This topic is too big for me, though. Here are a few articles on the topic:

- These are the 15 western brands Chinese people love the most

- Defying Tough Times, These Four Foreign Brands Are Successful in China

- Hurun Best of the Best Awards 2015

10. “Do you ever get culture shock over there?”

Not really. I do have my bad days in China, but that’s to be expected, right?

I’d say it’s probably a good idea to expect culture shock, but actually, the less you expect at all, the less shocked you are. I arrived in China as a wide-eyed 22-year-old full of wonder, and just took it all in.

11. “What do Chinese people think of [insert foreign brand/person/country]?”

The state may control the media in China, but it doesn’t control the opinions of individuals. Sure, you’ll meet lots of people that parrot the party line echoed in the media, but you’ll also meet lots of people with their own ideas.

So what I’m saying is: you’ll find all kinds of opinions on any topic. That’s why the Sinosplice tagline is “Try to understand China. Learn Chinese.” The more people you can talk to, the more you’ll be able to appreciate the diversity of opinions and ideas here in China.

12. “What does China think of Trump?”

Again, lots of opinions here. Many people think he’s an idiot, and many think he’s an accomplished businessman. I wrote about this a bit last year.

13. “Do you have a Chinese [wife/husband] yet?”

Yup. I’ve been married since 2007.

14. “So how much longer do you think you’ll stay over there?”

Most expats arrive in China without expectations to stay too long, and most only last a year or two. (The “interestingness” can get overpowering.) I was originally my plan to only stay 1-2 years as well, but eventually I decided to stay indefinitely.

I anticipate I’ll be spending some part of the year in China for the rest of my life, but I do plan to spend more and more time in the States, as I have started doing in recent years. I want my kids to spend more time with my parents, and to absorb some more American culture. Trips to the U.S. are also becoming increasingly important for my businesses, AllSet Learning and Mandarin Companion.

One common trend among expats in China is that once they have kids, they tend to leave so that they can put their kids in school in their home countries. (Even the Chinese who can afford it are trying to put their kids in school outside of China, and it’s becoming really common for high school, even, among families that can afford it.) My kids are 5 and 2 now, so there’s not a huge rush, but it is a factor too.

15. “When are you coming back for good?”

Once you marry into China, there’s no “coming back for good,” as far as I’m concerned.

16. “But really… are you ever coming back?!”

These questions are starting to sound like my mom.

14

Dec 2016NES Classic in Shanghai

How much would you pay for a little plastic box of Nintendo nostalgia? In the US, the NES Classic is going for around $200 on Amazon, while the Euro version is selling for around $230, and the Japanese version for $140 (which you better read Japanese for). I’m not sure how guaranteed the device is to be in stock, even at those prices, however.

So I was a little excited to find stacks of these things at a game shop in Shanghai on West Beijing Rd. (北京西路), near Jiaozhou Rd. (胶州路). The price for the Euro version is 900 RMB (about $130 at current exchange rates).

If you’re in Shanghai and want to seek out the shop, stay on the south side of the street east of Jiaozhou Rd, and look for a blue Playstation sign.

06

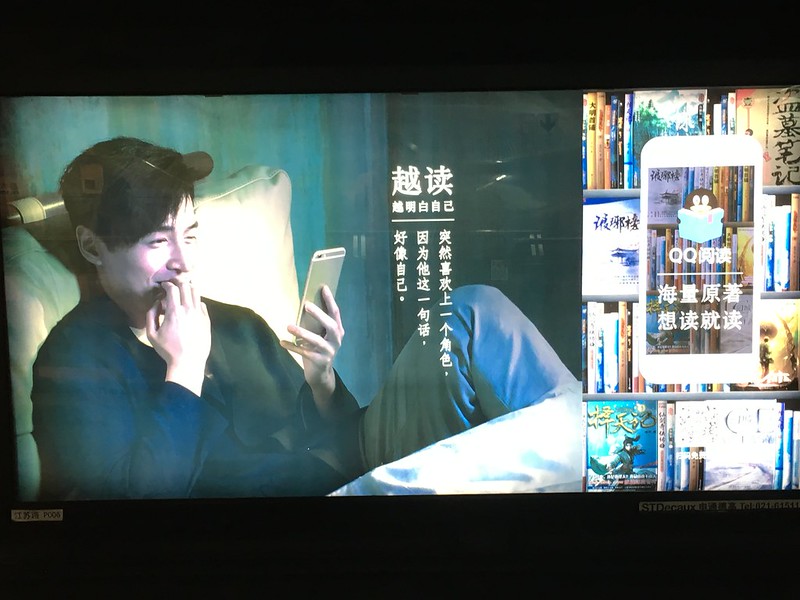

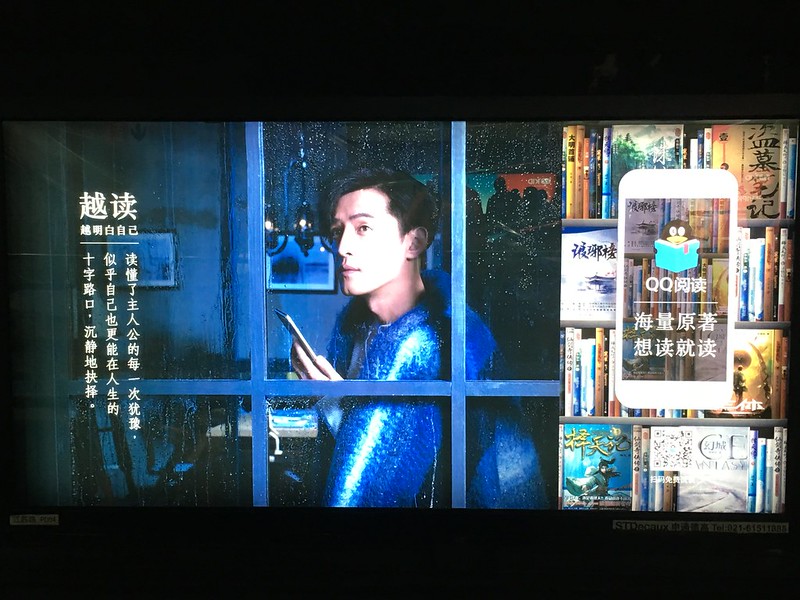

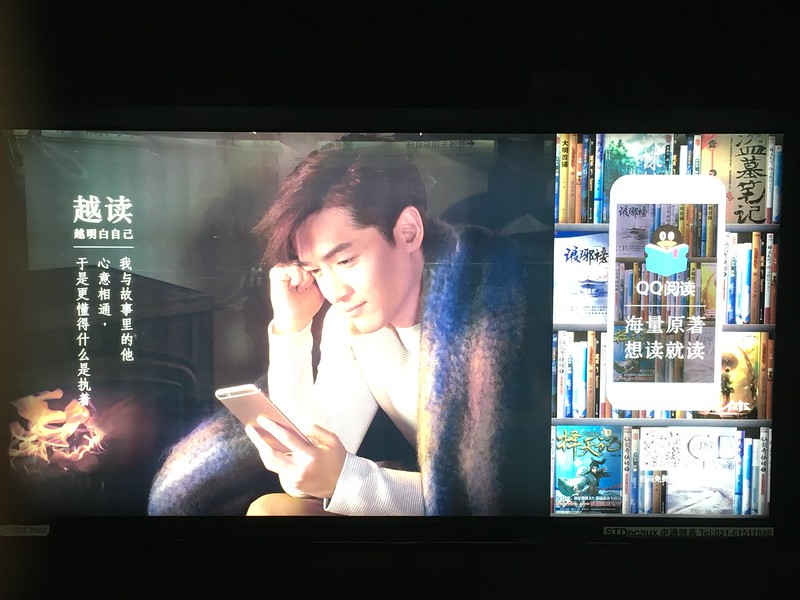

Dec 2016The more you read…

I like these subway ads for the QQ阅读 app:

The ads have been running for months already. The app is QQ阅读, an ebook reader app. 阅读 in Chinese can mean “to read” or “reading.”

The main line in the ad is:

越读,越明白自己。

The more you read, the more you understand yourself.

It’s a great usage of the 越……越…… (the more… the more…) grammar structure. But, in case you didn’t notice… it’s also a pun. It’s an ad for QQ阅读 (Yuèdú), and it starts with 越读 (Yuè dú).

This is one of the least cringeworthy ads I’ve seen in Chinese marketing, I must say! (No, I haven’t tried the app.)

02

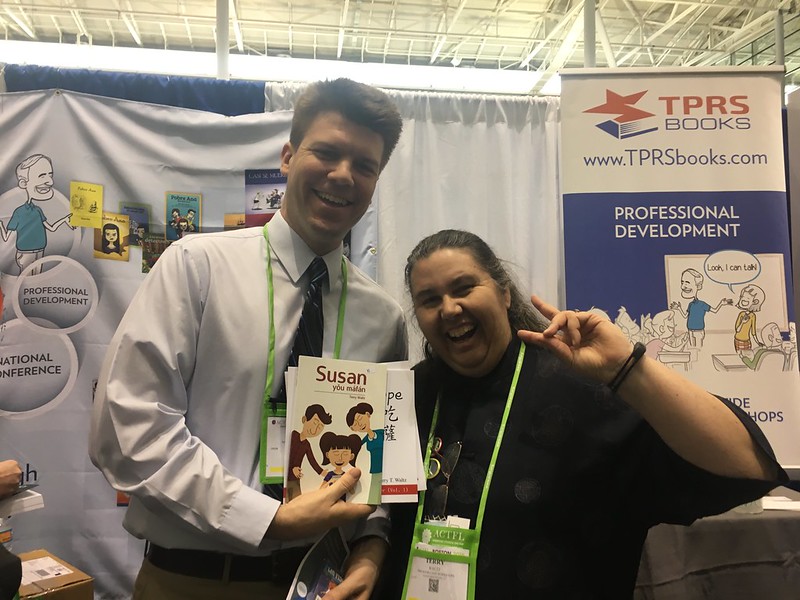

Dec 2016Back from ACTFL (2016)

I’ve been back from ACTFL for a while, but immediately upon returning I discovered that a bunch of my websites (all hosted on the same shared server) had been infested with malware. So I had that to deal with, in addition to a mountain of other pre-Christmas things.

The server was likely infected because an old WordPress install (that should have been deleted) was exploited. The best fix was a clean wipe: change passwords, export WordPress content via mySQL database dump, re-install WordPress, and re-import each website’s content. Fortunately, my web hosting service, WebFaction, was really helpful. They detected and alerted me of the malware in the first place, and provided useful guidance helping me clean it up. WebFaction is not the best service for anyone relatively clueless about tech, but if you can handle SSH and, like me, don’t mind Googling Linux commands occasionally to get stuff done, it’s really excellent.

But back to ACTFL… It was great to talk to the teachers I met there, and although I was there representing Mandarin Companion this time, I also met teachers familiar with Sinosplice, AllSet Learning, and ChinesePod. It was invaluable to get this rare face-to-face teacher feedback.

Here are my observations from the conference:

- I was last at ACTFL in 2008, when almost all Chinese teachers in attendance were university instructors, with a sprinkling of teachers from cutting-edge high schools. Now there are plenty of high schools, middle schools, and even primary schools represented. So one unexpected piece of positive feedback was that even middle schools can use Mandarin Companion’s graded readers, and the kids like them.

- In 2008, pretty much all Chinese teachers in attendance were ethnically Chinese. The only exception I can remember was my own Chinese teacher from undergrad at UF, Elinore Fresh (who was a bit of an anomaly, having grown up in mainland China). But now many of those non-Chinese kids that studied Chinese in college and got pretty good at it have become Chinese teachers themselves, and are also attending ACTFL. I’ve always been a proponent of the learner perspective in language pedagogy, so this is a fantastic trend to see. Chinese and non-Chinese teachers can accomplish so much more by collaborating.

- There’s a strong TPRS (Teaching Proficiency through Reading and Storytelling) faction at ACTFL, the lead proponent for its application to Chinese pedagogy being Dr. Terry Waltz. I got a chance to talk to her about her methods, as well as other practitioners such as Diane Neubauer, who contributes to a great blog dedicated to TPRS for Chinese called Ignite Chinese. It’s very encouraging to see classroom innovation in this space, and I am researching TPRS more.

- Boston is a pretty cool city. I regret that I didn’t have the time to check it out properly.

When I attended ACTFL in 2008, I met the guys behind Skritter, which went on to become a world-class service. I didn’t make any similar discoveries this time, but there’s no substitute for direct communication with all the teachers back in the USA working hard to prepare the next generation of kids for a world that needs Chinese language skills more than ever. I expect to be attending ACTFL pretty regularly in the coming years.

Now for some photos!

16

Nov 2016Headed to Boston for ACTFL

I’m now in Boston for the ACTFL convention. It’s a gathering of a bunch of professional language teachers from all over the U.S. The last time I was here was in 2008, representing ChinesePod. This year I’m representing Mandarin Companion. (We’ve got a new book out, by the way: Journey to the Center of the Earth.)

I’ll be connecting with a few people at the convention, and meeting up with my Chinese teacher buddies. I also get to visit my sister Amy and high school friend Steve. If you’re a Sinosplice reader and you’re at ACTFL, though, please seek out Mandarin Companion and come by and say hi!

15

Nov 2016Naughty Beer

Thanks to reader Lucas, who lives in 张家港 (north of Suzhou), for sharing this image:

The pun is pretty simple:

- 啤酒 (píjiǔ) beer

- 顽皮 (wánpí) naughty

So the 皮 was swapped for the 啤 (they sound identical), and “naughty beer” was born!