23

Sep 2011China Daily Show is great

Maybe I don’t read the right blogs, but it seems like China Daily Show isn’t getting nearly as much attention as it deserves. This China-centric Onion-style “news” site is hilarious. It describes itself like this:

> China Daily Show is not affiliated with China Daily or The Daily Show and is intended for humorous purposes only. All events, characters, names and places featured are products of the authors’ imaginations, or are used fictitiously.

Here are some recent headlines to get you started:

– 80% of Chinese cuisine ‘shanzhai’: expert

– WHO downgrades Chinese culture to “cult,” urges strong caution

– Thousands of men now straight after gay website blocked in China

– Biden completes “Man of the People” tour by becoming Beijing cabbie

– Tibet, Xinjiang vital to keep China chicken-shaped: WikiLeaks

– Chinese skipper snares, eats mermaid

– Beggar not actually an erhu player: Erhu player

21

Sep 2011My Favorite Shanghai Busker

There are a lot of buskers in Shanghai. I’m not sure how most people feel about them. I certainly don’t mind the blind guys playing erhu, or the guitarists in the park. But rarely do I actually really like their performances. I enjoy hearing this guy every time I catch him on the stairs of Exit 2 at the Zhongshan Park Line 2 subway station:

He plays piano music on his boombox, and then accompanies it on his (amplified) violin. It sounds really good! I’ve heard mostly classical pieces by him. He’s playing Pachelbel’s Canon here.

His sign reads:

妻乳腺癌

儿上大学

功德无量

谢谢

In English, it’s something like:

Wife has breast cancer

Son in college

Your kindness will be rewarded

Thank you

Note: I took liberties with the 功德无量 line, which comes from Buddhism, and is translated as “boundless beneficence” in the ABC dictionary.

15

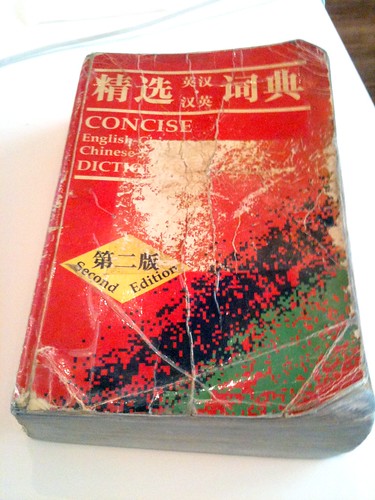

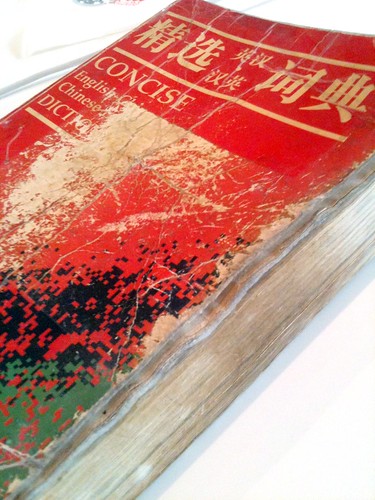

Sep 2011Ode to a Paper Dictionary

The Oxford Concise English-Chinese Chinese-English Dictionary is a solid dictionary. It’s a great compromise between “comprehensive” and “portable,” and it’s the one I had with me in my early days in Hangzhou, when I had to look up every other word that I heard. I started with the “handy pocket-sized” version, but I quickly realized that even though it was half the size, it was still a little brick of paper I had to slug around, and the characters were just way too small at that size. So I used the medium-size brick of paper comfortably for years.

I still have that dictionary, although it’s showing its age. Over the years, I have had to use packing tape to reinforce its edges and spine, but at least I managed to do that before it started totally falling apart. Here’s what it looks like now:

Slightly worn, you might say.

When I used this dictionary regularly, I used to highlight words, phrases, and sentences that popped out at me as being useful or somehow study-worthy. What’s great is that I can still browse the dictionary now and see what I once highlighted. Sure, nothing is dated; there is no metadata. But it’s enlightening and amusing to flip through this paper record of my progress.

A little sample:

– 避免 to avoid

– 关心 be concerned about

– 关于 about; on; with regard to; concerning

– 上当 be taken in

– 下流 obscene; dirty

– 大海捞针 look for a needle in a haystack [I’m pretty sure I never ever had a chance to use this, even if I managed to memorize it briefly]

You get the idea.

But the point of this post is not to recommend a great dictionary. I used that dictionary every day for a very important period in my life, and it facilitated all sorts of conversations on a regular basis (yes, I was one of those annoying students that would occasionally put a conversation on hold if there was a word I felt I just really needed to know right away). And yet, I don’t recommend that dictionary much at all. Nowadays I regularly recommend Pleco (and sometimes Wenlin) to AllSet Learning clients, but not paper dictionaries.

Why? Well, there are a number of reasons…

– Most people don’t want to carry around a heavy book, but they take their cell phones everywhere

– Most people find looking up words in a paper dictionary quite a hassle

– Electronic dictionaries are so fast, and with one more touch you’ve saved the word as well for later reference

I remember when I first came to China, lots of people were using mini hand-held electronic dictionaries. They were great, except that (1) they rarely provided pinyin for English-Chinese lookups, and (2) they had short dictionary entries with very few sample sentences. Well, those days are over. The day has finally arrived, and entries are now bursting with information, while internet connectivity offers potentially limitless sample sentences.

So why am I still a little sad? Well, there’s definitely something to be said for idly flipping through those pages made of paper. I’m not sure why dictionary serendipity of the eyes-to-paper variety feels more special than dictionary serendipity of the search-and-related-data variety, but it does. And looking at that old battered paper dictionary, its mere existence does feel meaningful. I beat the crap out of that thing with my learning, and then did just enough work to keep it on life support. And now I neglect it, relegating it to a bathroom book, while computer-based dictionaries serve my daily needs.

We had some good times, paper dictionary. It’s not you, it’s me. But relationships change.

13

Sep 2011On Moon Cake Economics

Happy Mid-Autumn Festival, a day late. I managed to get out of eating moon cakes this year. (Whew! My moon cake eating contest days are behind me…)

Photos of Shanghai residents lining up to buy moon cakes (月饼), rain or shine (but always with umbrellas), from Jing’an Temple in the month leading up to Mid-Autumn Festival:

I’m not going to say much on economics, but this whole “moon cake economy” thing strikes me as quite interesting. While in a taxi the other night, a guest on a radio talk show made some interesting points:

1. The value of moon cake coupons has exceeded the value of the moon cakes themselves.

2. Some people eat moon cakes, but a lot of people just pass them around, gifting and regifting. (The actual quote was: “买的不吃,吃的不买,” literally, “those who buy them, don’t eat them, and those who eat them don’t buy them.”)

3. As the moon cake economy evolves, more and more products are being used as substitutes, such as ice cream moon cakes, soft mochi moon cakes, non-traditional cake as moon cakes, etc.

It’ll be interesting to see where this tradition goes in the next ten years. Will the Chinese try hard to preserve it as is, or will they morph into into something else?

Related links:

– Mooncake becomes the fruitcake of China – L.A. Times, 2011

– Mooncake economics – Global Times, 2011

– A black market for mooncakes in China – Marketplace, 2010

07

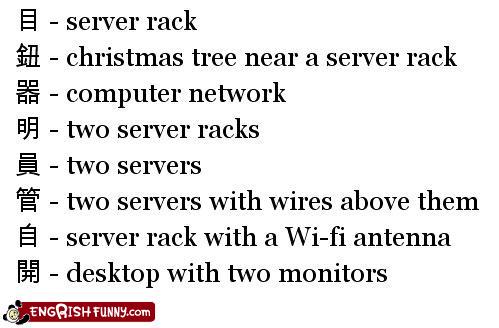

Sep 2011Chinese Characters for Servers

My friend Juan recently brought this amusing use of Chinese characters to my attention:

The characters used are:

– 目: mù

– 鈕 (simplified: 钮): niǔ

– 器: qì

– 明: míng

– 員 (simplified: 员): yuán

– 管: guǎn

– 自: zì

– 開 (simplified: 开): kāi

01

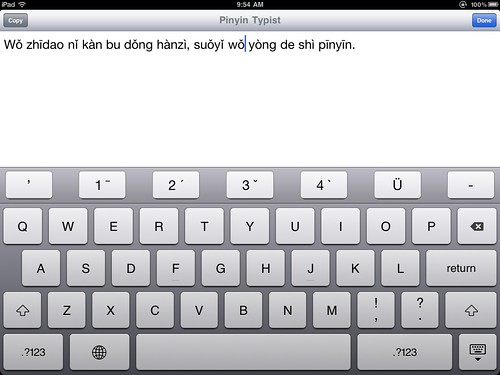

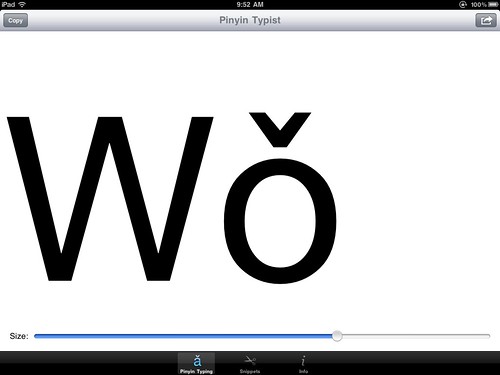

Sep 2011Pinyin Typist for iPhone, iPad

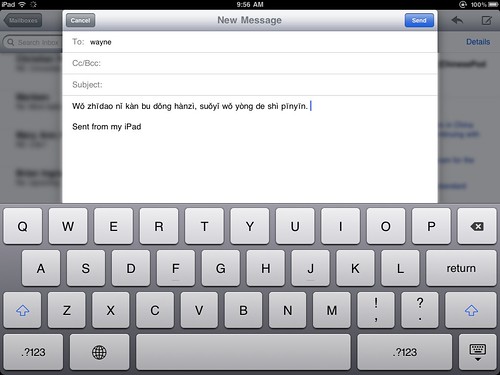

Pinyin Typist is an app for the iPhone and the iPad which allows for easy pinyin input with proper tone marks. Note that it is not an input method; you can’t use this app to switch between English and pinyin input like you can with Apple’s built-in language input support. But it turns out that Pinyin Typist works even better as an app rather than an input method.

In the screenshots below, I’ve used the iPad version of the app. Note that you can adjust size of the pinyin text (larger text makes pinyin tone marks much easier to make out). Pinyin tone input works pretty much as expected; just type out a syllable, then hit a number to add the tone mark. You can be pretty sure that tone marks are implemented correctly, because even Mark Swofford (of pinyin.info) has given it the nod. I have found no problems with it.

In case it’s not entirely clear, the way to use this app is to open Pinyin Typist, type pinyin with tone marks, then hit the app’s handy “Copy” button, switch to another app (like the “Mail” app pictured above), and paste in the pinyin.

[Update: clarification from the developer] Actually, in Pinyin Typist you can also directly email the text in its Pinyin Typing tab view, and you can also directly email the title and text of a saved snippet from its Snippets tab view, without leaving the app and switching to another one. (The button that reveals those direct emailing commands is the one on the top right.)

I find switching apps to type pinyin and copy it over is actually a good way to do it, simply because I don’t use pinyin very often. Yes, I do use it occasionally, and for those occasions this app is very handy. But if the pinyin were an actual input method, it would be pretty annoying to have to cycle through it every time I wanted to switch between English and Chinese input (which is often). I had to remove Chinese handwriting input because pinyin input is almost always faster to input, and having the extra input method there in the way was just too annoying.

The one problem I have found with the app is that because I’m actually typing in English mode, iOS’s autocorrect (damn you, autocorrect!) sometimes “corrects” a pinyin syllable. This isn’t a problem when there’s a tone mark on the syllable, but it’s sometimes a problem when the syllable has a neutral tone. For example, when I typed “zhīdao” above, iOS originally correct it to “zhīSao” (no idea why). It’s a fairly minor issue, though.

The app is not free (it’s currently $2.99), which raised in interesting question for me: how important is it to be able to type pinyin on iOS? I’ll admit that I use pinyin a lot more on my regular computer than on my iPhone or iPad. I do need to frequently provide pinyin for AllSet Learning clients, but not via my iPhone or iPad. It seems like this app would be especially useful for a Chinese teacher who frequently texts students, or who sends a lot of email on an iPad or iPhone.

I raised this issue with the developer of the app, Wayne. He’s also very interested in learning more about how potential users will use his app. As a result, he volunteered to provide 5 free copies of Pinyin Typist for Sinosplice commenters who leave an insightful comment below and explain why the app will be useful to them on their iPhone, iPad, or iPod Touch. (If you have other comments about the price, you can leave those too, but be nice.) The developer will choose the 5 winners from the comments himself, and I’ll provide him with the email addresses so that he can award the app to the 5 winners (so be sure to use your real email addresses; the blog will never publicly display them).

Update: The developer has chosen the 5 winning commenters; you should be hearing from him shortly!

29

Aug 2011The Four Great Ugly Women of China

Recently ChinesePod was preparing to do a podcast on some of the “Four Greats” (四大) of China [more info in Chinese]. If you’re not familiar with any of these, you might want to listen to the podcast (it’s free). Otherwise, a quick sum-up of some of the most famous ones will suffice:

- 四大发明 (the Four Great Inventions of Ancient China)

- the compass

- paper

- gunpowder

- printing

- 四大名著 (the Four Great Classic Literary Works)

- 红楼梦 (Dream of the Red Chamber)

- 西游记 (Journey to the West)

- 三国演义 (Romance of the Three Kingdoms)

- 水浒传 (Water Margin)

- 四大美女 (the Four Great Beauties)

- 西施 (Xi Shi)

- 王昭君 (Wang Zhaojun)

- 貂蝉 (Diao Chan)

- 杨玉环 (Yang Yuhan, AKA Yang Guifei)

The funny thing is that in addition to the “Four Great Beauties” (of ancient China), there are also “Four Great Ugly Women” (who don’t seem to have their own Wikipedia page):

- 四大丑女 (the Four Great Ugly Women)

- 嫫母 (Mo Mu)

- 钟离春 (Zhong Lichun)

- 孟光 (Meng Guang)

- 阮氏 (Ruan Shi)

I talked to a ChinesePod co-worker about these famous ugly women. The conversation went something like this:

> Me: So these women were so ugly that they went down in the history books just for that? Isn’t that kind of mean?

> Her: Well, they weren’t just ugly. They also had great talent.

> Me: Well, why not just call them “the four great women of talent” then?

> Her: Well, they were also ugly.

Point taken. Cultural lesson learned!

26

Aug 2011Shanghai Internships for Learning Chinese

Today marks the end of the summer internships at AllSet Learning. We had our first intern, Donna, last summer. That was when the company was just starting out. Since we now have quite a few more clients and a whole team of teachers, there were a lot more interesting tasks for this summer’s interns, Lucas and Hugh. And their internships were pretty cool, directly related to learning Chinese.

Some of the things the AllSet Learning interns got to do:

– Take demo lessons to help evaluate different teachers’ teaching methods

– Play with “Chinese character building blocks” (a children’s educational toy set), experimenting with Chinese character constructions

– Provide feedback on various types of learning materials, from comics to Communist Party doctrine to iPad apps

– Help research and compile Chinese grammar information

– Test the effect of regular tone pair drills

– Participate in game-like components of teacher training sessions

– Play Settlers of Catan (and explain it in Chinese)

– Eat 东北菜 (pictured above)

One of the things I personally gained from having the interns around the office was a reminder of the very specific early challenges learners of Chinese face. But I also saw firsthand how the new generation of learners is coming to China much better prepared and knowledgeable. One of my interns, Hugh, even has an excellent blog on learning Chinese called East Asia Student. I’ve mentioned it before, but the days of coming to China clueless and expecting to have opportunities thrown at you really are winding down (or at least moving to China’s smaller cities).

Anyway, if you’re a bright young mind looking for an internship that offers the opportunity to learn Chinese, we’ve got them at AllSet Learning.

And finally, a sincere thank you to Lucas and Hugh for their hard work this summer. You guys were great!

23

Aug 2011The Rare Chinese Font

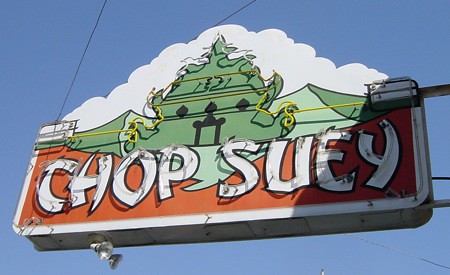

You know “the Chinese font“? The one that just screams Oriental, because it looks like it’s made out of bamboo pieces (?), mystically arranged by a wispy-bearded kung fu master?

In case you don’t know what I’m talking about, let me remind you:

Well, the above font is one that, in my experience, you’ll be hard-pressed to find in mainland China, especially in Chinese. (Anyone out there have a different experience?) Most typed Chinese here is in one of about 4 fonts, and “Oriental” isn’t one of them. This shouldn’t come as a surprise, I suppose; the Chinese just have no reason to parody themselves.

There’s a place on the way to the AllSet office in Shanghai that actually uses the “Oriental” font, though, in Chinese. This is a rare find. Here it is:

That’s a dry cleaner’s window. The “Oriental font” is in the middle. It says, 八折价, which means “80% of the original price.”

Mystical indeed.

19

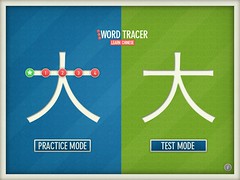

Aug 2011Word Tracer Apps for Sinosplice Readers

A while back when I wrote my Learning to Write Chinese Characters on the iPad post, I reviewed an iPad app called Word Tracer. Word Tracer is going strong, and now comes in both iPad and iPhone flavors. In addition, the developer has added some additional functionality to the app in a recent update, allowing for Chinese writing practice that isn’t strictly “tracing.”

Anyway, to thank me for the review, the developer has offered me a number of free copies of the app (iPad or iPhone) to distribute to Sinosplice readers. If you’re interested in getting a free copy of this app, simply leave a comment here (with your real email) or send me an email explaining why you think that the iPad (or iPhone) makes the most sense to you as a way to practice writing Chinese. I’ll award the best ones in the first 48 hours with a free copy of Word Tracer. (Be serious in your replies; I’m very interested in learning something from this!)

Update: Thanks to all of you who commented and emailed me! The response was really pretty good, and I regret that there are too many of you for everyone to get a free copy of the app. I do appreciate the responses, though, and those selected will receive an email shortly. I’m closing comments on this blog post now.

16

Aug 2011The Three De Song

Learners of Chinese confront the “de triple threat” of Chinese structural particles pretty early on. You see, there are three different characters to write what sounds exactly the same to the ear. The three characters are 的, 得, and 地, each pronounced “de” (neutral tone) when serving as a structural particle.

If you’re just trying to improve your listening and speaking, you don’t really need to worry about this issue. If you’re working on your writing, however, you’re going to want to get it straight. I found the following (simplified) approach helpful:

- …的 + Noun

- Verb + 得…

- …地 + Verb

OK, yes, it leaves out a lot of special cases, and the aforementioned “Verb” in “Verb + 得” can also be an adjective. But they’re nice rules of thumb if you’re looking for something a bit simpler.

But here’s the interesting thing: because the issue of the three de’s is one concerning writing and not speaking, Chinese native speakers themselves have to learn these rules, and can sometimes get tripped up. Some people who don’t need to write for a living might even just “opt out” of the whole issue and use 的 exclusively.

But because Chinese children have to learn to use the proper “de” in school, there is actually a children’s song about the three de’s! [source]

> 《的地得》 儿歌

> 左边白,右边勺,名词跟在后面跑。

美丽的花儿绽笑脸,青青的草儿弯下腰,

清清的河水向东流,蓝蓝的天上白云飘,

暖暖的风儿轻轻吹,绿绿的树叶把头摇,

小小的鱼儿水中游,红红的太阳当空照,

> 左边土,右边也,地字站在动词前,

认真地做操不马虎,专心地上课不大意,

大声地朗读不害羞,从容地走路不着急,

痛快地玩耍来放松,用心地思考解难题,

勤奋地学习要积极,辛勤地劳动花力气,

> 左边两人就使得,形容词前要用得,

兔子兔子跑得快,乌龟乌龟爬得慢,

青青竹子长得快,参天大树长得慢,

清晨锻炼起得早,加班加点睡得晚,

欢乐时光过得快,考试题目出得难。

I find the explanation of 得 a bit suspect. It “comes before adjectives”? Kinda misleading (but then again, so is “after verbs”).

I tried to find an online video of this song, and instead found a very similar but different song also about the three de’s:

The amusing thing about this video is that in at least one place, the subtitles get the “de” wrong. (Can you find it?)

05

Aug 2011Continent Names and Region Names in Chinese

Although not actually very complicated, the names of continents and world regions can trip up a student of Chinese. It’s not the continent names that are hard, it’s that knowing the continent names can lead one to incorrect inferences about the names of various world regions. An AllSet Learning client (this is for you, Stavros!) recently reminded me of this fact. I struggled with this myself not so long ago. Because no one ever took the time to lay it out for me, it took me forever to piece it together on my own.

Basically, the way it works in Chinese is like this:

1. If it’s a continent, it ends with the suffix –洲. (You can think of 洲 as representing the meaning “the continent of….”)

2. If it’s not a whole continent you’re talking about, drop the 洲.

So that means, for example, that “Western Europe” is not ×西欧洲, because it wouldn’t make sense to say “the continent of Western Europe.” Drop the 洲, and you get 西欧, the correct way to say “Western Europe.” It’s as easy as that. (I say “easy,” but I know I said ×西欧洲 quite a few times before anyone ever told me, “we never say that; just say 西欧.”)

These examples below should help drive the point home:

- 亚洲 – Asia

- 东亚 – East Asia

- 东南亚 – Southeast Asia

- 中东 – the Middle East

- 欧洲 – Europe

- 北欧 – Northern Europe

- 西欧 – Western Europe

- 东欧 – Eastern Europe

- 非洲 – Africa

- 北非 – Northern Africa

- 南非 – South Africa (the country)

- 西非 – West Africa

- 东非 – East Africa

- 澳洲 – Australia

- 南极洲 – Antarctica (literally, “South Pole Continent”)

- 北美洲 – North America

- 南美洲 – South America

A couple final complications…

1. You don’t often divide either Antarctica or Australia into regions in Chinese

2. You can also say 美洲, which means something like “the Americas”

3. Because 北美洲 and 南美洲 already have cardinal directions built into their names, it’s awkward to try to use the short form (like ×东北美 or something).

So the world region names are actually pretty simple, no 洲ke…

03

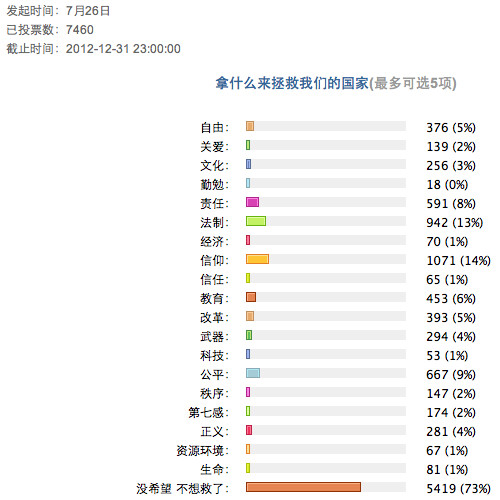

Aug 2011What can save this country?

In the wake of China’s recent bullet train disaster, I came across this poll on 开心网 (kaixin001.com):

Transcription:

拿什么来拯救我们的国家? (最多可选5项)

- 自由

- 关爱

- 文化

- 勤勉

- 责任

- 法制

- 经济

- 信仰

- 信任

- 教育

- 改革

- 武器

- 科技

- 公平

- 秩序

- 第七感

- 正义

- 资源环境

- 生命

- 没希望 不想救了

Translation:

What can save our country? (choose no more than 5)

- freedom

- love

- culture

- diligence

- responsibility

- law

- economics

- faith

- education

- reform

- weapons

- technology

- fairness

- order

- the 7th sense

- justice

- natural resources

- life

- there’s no hope; don’t want to save it

In case you missed it in the original image, 73% of respondents (over 5000 in total), most of whom are young people, chose the final answer.

It’s not an easy time to be Chinese.

27

Jul 2011Thoughts on an American Job Applicant on Chinese TV

I’ve mentioned before that I occasionally indulge in the Chinese dating show 非诚勿扰. There’s another one of these reality TV-type Chinese shows that I watch from time to time called 非你莫属 (English name: “Only You”). On this show, each entrant is a job applicant given a chance to explain the type of job he’s looking for and interview with a panel of 12 bosses right there on camera. If all goes well, the bosses make offers to the applicant, and details of salary are discussed right on the show. Finally, the applicant is given a chance to accept the final offers or decline them and leave the stage.

This show is appealing for a number of reasons. There is quite a range of applicants, from young kids with no experience, to senior citizens, to the destitute and desperate, to the physically abnormal. Quite a few of the applicants just plain don’t have much to offer. The “bosses,” who are on the show to promote their own companies, can also say some interesting things. Perhaps one of the most compelling aspects to me is seeing what kind of job offers are made on the show, and what salaries the applicants will accept.

After watching this show for a while, I was surprised to see recently that there was a young American applicant. Unlike 非诚勿扰 (the dating show), which has had quite a few foreigners on the show, I’d never seen it on this show. The applicant was a 25-year-old white American male named Nathan (Chinese name: 尚德). Having lived in Beijing for a while, Nathan spoke pretty solid Chinese, and had no major issues communicating on the show. But the bosses’ reactions to Nathan were not quite what I expected.

Before I go on, some links are in order:

* A Sohu TV link to the video (the segment discussed here is 01:06-16:05)

* A Google Docs link to the Chinese transcript (01:06-16:05)

24

Jul 20112011 Update for Sinosplice

The Sinosplice blog has recently undergone a few minor upgrades, including:

1. Vastly improved search. (It was terrible before. I myself used to use Google to find content on my own site.)

2. Social sharing icons. (I tried to avoid this for quite a while, but it’s a trend that won’t be ignored! My reward for waiting was being able to include G+ easily.)

3. Automated related post info. (I’ve been meaning to do this for a long time. Scroll down on a post or page to see related posts, NYTimes-style.)

4. iPhone optimization for cell phone viewing.

5. Tiny style tweaks.

Please let me know if anything doesn’t sem to be working right for you. You may need to clear your cache and/or reload the page a few times.

Thanks to Ryan from Dao by Design for once again doing a great job and being so easy to work with.

21

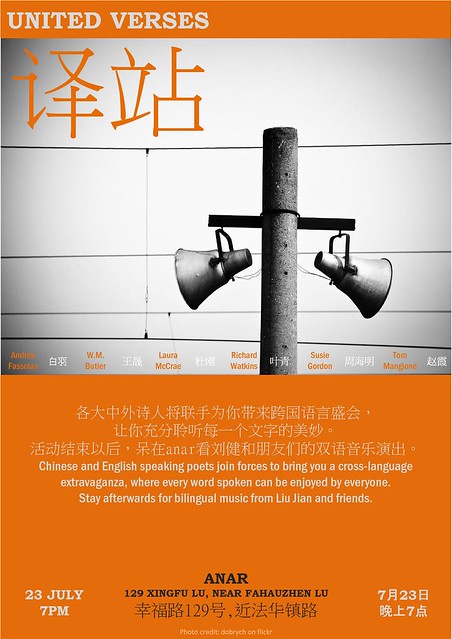

Jul 2011United Verses

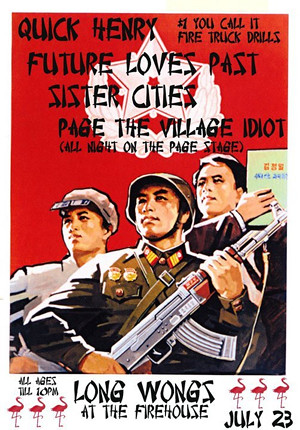

My friend Tom (mentioned once before here) has put together a really cool event which he’s calling “United Verses” (译站 in Chinese). The concept is basically a bilingual poetry reading event. Each Chinese poet will read his poems in Chinese, and then an English-speaking partner poet will read English translations of them. That English-speaking poet will later read his own poems, and his partner poet will read the Chinese translations.

This is a really cool cross-cultural activity, and I applaud Tom for putting it together. It took a lot of work to coordinate translators behind the scenes, because the poets themselves aren’t usually the translators. Additional translators are needed, both native Chinese speakers and native English speakers.

I participated as a translator myself (as did one of my AllSet Learning clients), and I found it a really interesting and rewarding experience. Not only do you get to discuss the meaning behind the poem with the original poet, but then you also get to discuss your translation into English with an English-speaking poet. This isn’t just basic off-the-cuff translation, and the resulting translations are quite solid.

Unfortunately I won’t be able to be at the event myself, because I’ll be out of town. I leave you with a photo of “my poet,” 叶青, a very interesting Shanghainese man, pictured here in his study.

Finally, the event details in plain text:

> United Verses (译站)

> July 23rd, Saturday 7pm (event starts around 8pm, but seats are limited)

> at Anar: 129 Xingfu Lu, near Fahuazhen Lu (幸福路129号,近法华镇路)

14

Jul 2011I miss Best Buy

The other day I went to Chinese electronics retail giant Suning (苏宁) to pick up a new USB drive. I’ve never been impressed by either Suning or Gome (国美), but my most recent visit made me wonder if with Best Buy’s recent closing, they’ve just kicked back and completely stopped trying altogether.

I was looking at Sandisk’s USB drives, eyeing the 8 GB one, and then I noticed an equally compact 16 GB version. I asked the price, which wasn’t listed. The exact same model 16 GB drive was quite a bit more than twice the price of the 8 GB model. Hoping against hope, I asked if this wasn’t a little strange (check here for an example of normal pricing on Amazon), and that if she might have gotten the price wrong. I forget what the salesperson said, exactly, but the message was clear: “I think you’re confusing me with someone who gives a damn.”

Anyway, I decided to go with the 8 GB version, but I forgot that I wasn’t at Best Buy anymore. I couldn’t take my selection to checkout, I had to take a special number to the far side of the store to make my payment in a carefully hidden location. But the amusing thing was that my order number was not printed out, or even handwritten on a standard form. No, it was scrawled on a random scrap of paper. Classy.

Anyway, I found the cashier in a desolate corner of the store and made my payment. (Apparently the number wasn’t made up, at least.) I located the original salesperson, wondering where my purchase was. She had cast it aside on a random shelf under some earphones. She retrieved it for me. I asked for a bag. Sorry, no bags.

So, walking towards the exit with my unbagged purchase, I wondered how I looked any different from a shoplifter just making off with an item plucked from the shelves. Many Chinese stores that use the “cashier all the way across the store and nowhere near the exit” system have a guard at the exit who checks for a receipt. At Suning, there were no guards, no employees in sight. Just a big wide swath of apathy pointing the way out.

Yeah, I must admit that I miss Best Buy. I still think “service” is a good idea.

12

Jul 2011Z-ZH Wordplay

I’m wondering if this ad would be as likely to be used in northern China:

The text of the ad is:

> 招租!找主!

The pinyin for the ad is:

> Zhāozū! Zhǎo zhǔ!

If you ignore both tones and the z/zh distinction (which a lot of southerners–especially elder southerners–do frequently), you get this:

> Zao zu! Zao zu!

The meaning of the ad is something like, “For rent! Seeking the right person!” (“主,” often meaning “host” or “owner” is a bit tricky to translate, because normally someone in a position to rent is not a “主,” but in this case that’s who it refers to: the appropriate party to do the renting.)

07

Jul 2011Transformers and… Milk?

With the movie Transformers 3 now out, Transformers are popping up in Chinese media more too. The other day I snapped these pictures of an ad campaign involving 舒化 milk. (Sorry the photos are blurry… I have yet to figure out the best way to consistently get clear photos of back-lit subway ads with my cell phone.)

OK, kids like Transformers, kids drink milk. Still, badass robots drinking milk? It seems kinda off. (Stop messing with my childhood memories!)

04

Jul 2011Please speak Mandarin (or laugh at me)

Quite a while ago I made a shirt which had 请讲普通话 (“Please speak (standard) Mandarin”) on the front, and started selling it on the Sinosplice store (through CafePress). The idea is that if you challenge the people around you to talk to you in Chinese, they probably will. It wasn’t until my last visit to the States in February that I was able to pick up my own “Please speak Mandarin” t-shirt, and not until the weather warmed up recently that I was actually able to see the effect.

The first time I used it was in a cafe, where the waiter insisted on talking to me in English, even though I initiated in Chinese. It was a classic language power struggle. I pointed to my shirt and asked him to 请讲普通话, which was incredibly awkward for me to do. He then got it, but clearly found it extremely difficult to not use English with a foreigner.

Later in the day, I caught several girls reading my shirt, laughing, and pointing it out to their friends. They didn’t talk to me.

So, it’s only been Day 1 of the experiment, but so far empirical evidence suggests that this shirt may be amusing to Chinese girls. (My wife, on the other hand, found it a little embarrassing.)

Related: Other Sinosplice original t-shirts