02

Jun 2015The Chairman’s Bao

Since my job at AllSet Learning is to create personalized Chinese courses for clients, I’m always on the lookout for good new sources of study material. The most interesting and promising one I’ve found lately is called The Chairman’s Bao (主席日报). More than simply a collection of interesting articles in Chinese, the site describes itself as “the 1st ever online Chinese simplified newspaper dedicated to those learning Mandarin.” This is because each article has been written (simply) to conform to a specific HSK level. The lowest level on the site is currently HSK 3, the highest HSK 6+.

This is pretty awesome, considering that many learners despair of ever being able to read an actual newspaper until their overall levels are somewhere around “advanced.” I myself put off reading newspaper articles until I was almost ready for my graduate-level studies in Chinese. Some learners feel that browser extensions provide the reading help needed, but it’s still very easy to get discouraged if you’re looking up every other word in an article.

Essentially, this is a news-themed application of the graded reader idea. While the articles themselves are not long enough to be considered true extensive reading exercises, it’s still a refreshing take on the “study the news in Chinese” idea, and it makes news far more accessible to more learners than ever before.

Here are some of my observations about the service:

– It’s free! It might not remain that way, so check it out while you still can. It’s currently not even necessary to create an account to read articles and listen to audio, unless you want to save vocabulary words.

– You’ll need an account to use the built-in dictionary. The dictionary isn’t of the “mouse-over” variety, though; you actually have to select text with your cursor. This means that if you incorrectly parse a word, the dictionary is of little help. The good news, though, is that you can also use a popup dictionary extension on the site (which could also provide grammar links), and there will be no conflict with the built-in dictionary. Hopefully the built-in dictionary will improve over time. (If you use the built-in dictionary, though, you have the added advantage of being able to save words to your account on the site.)

– The articles are pretty well-chosen. While you may not be interested in everything, you can undoubtedly find some articles that interest you, and at your level.

– The articles’ audio recordings are clear, although sometimes the person reading seems less than enthusiastic. Considering that it’s provided for free, though, it’s quite good most of the time (no robot voices!).

– The site doesn’t tell you how many articles are on the site, but there are clearly a lot.

Because I had a number of questions about The Chairman’s Bao, I got in touch and actually met with one of the co-founders, Thomas Reid, who is also Chief of Staff. He was also gracious enough to do a mini-interview about the service:

John: How many total articles are on the site? Do you have a breakdown by level?

Tom: As of [May 28th], there are 254 articles that have been published on the site (HSK3: 60, HSK4: 68, HSK5: 73, HSK6/6+: 53). I’m afraid that there is no way to get these numbers on the site itself, however you can sort the articles by level and scroll down right until the first articles published from our launch in January. All articles are available to view.

John: What is your new article publication schedule? Do you have a breakdown by level?

Tom: We aim to publish 2-3 new articles a day. This was being achieved until recently when 2 of our staff left. As such we can only publish 1-2 per day. I am currently recruiting new writers and we will soon be back up to our original quota. As for the level breakdown, I try and keep it as even as possible with the number of articles being written and the days they are uploaded and published. However there are a lot of factors that can affect the timeline here, particularly the strict editing procedure. Sometimes in order to guarantee an article’s quality according to a certain level, modifications need to be made. This can slow down the time it takes for the article to be published.

John: How do you choose what articles to do, and who does it?

Tom: Myself and my partners [CEO] Matt Carter and [CMO] Sean McGibney choose the stories. We are constantly browsing news not just from within China but all over the globe to find our stories. The main focus is on China, but we will, of course, try to include major events and interesting developments from around the world.

John: How do you level your articles, and who does the work?

Tom: Once we have found the news, we add it to a shared folder and assign it an HSK level before sending it to the writers. We judge this on the content of the article. We need to look at what words must be used in order to tell the story in its most basic form. These words are a good indication of a suitable level. If they are relatively simple, then the writers can build sentences around them for low levels. More complex words will, of course, require high levels. The writers then write the articles and submit them to the site. The editors then check the articles to ensure a good style and verify the academic quality. Finally, audio is added and the article is published.

John: Do you have any cool new features planned that you can share?

Tom: We are currently designing the App for both iPhone and android. This has already started and will be finished in time for the next academic year.

I’m not going to do a full review including the vocabulary manager; I don’t use that myself. But there’s definitely a dearth of good study material out there, and it’s great to The Chairman’s Bao breaking new ground and addressing head-on one of the issues that has plagued us for so long: we want to read something interesting.

Check it out and spread the word!

27

May 2015Schrodinger’s Douchebag (Chinese version)

Original Schrodinger’s douchebag:

One who makes douchebag statements, particularly sexist, racist or otherwise bigoted ones, then decides whether they were “just joking” or dead serious based on whether other people in the group approve or not.

(In case you’re not clear on the original original reference, it’s to Schrodinger’s cat.)

Here’s the Schrodinger’s Douchebag, Chinese version (as presented on Quora by user Feifei Wang):

Schrodinger’s Douchebag, Chinese version

[…] Almost every time someone (White or Chinese Americans alike) ask me something about China, it’s always bad or weird: do Chinese people eat dogs? do Chinese people pee at street? are Chinese people still can’t afford this and that? do you have internet? Is it true that you really can’t get on facebook or google? What about Tibet and/or Taiwan? Do Chinese people killing infant baby girls because of one child policy? Just how corrupt is Chinese government?

From time to time, I think people get off on [asking purely negative questions about China]. People enjoy the feeling of superiority, that no matter how bad his personal life is, at least he’s better than someone. And they disguise that (intentionally or unintentionally) with a fake curiosity.

I call this Schrodinger’s douchebag – Chinese version: Someone would ask an offensive question about China and then decide whether they’re “just curious” or dead serious based on whether other people in the group approve or not.

Are there people how are really, genuinely curious about a certain bad aspect of Chinese culture? Sure there are. But the same kind of genuinely curious people are also interested in the good things about China as well. If someone comes to you asking only the bad things, you can just make an excuse and politely walk away from the conversation. People like this don’t deserve your time. They can rot in their ignorant and racist bigotry for all I care.

Of course, douchebaggery about China isn’t limited to those with little working knowledge of China. I had a conversation with a friend recently about the frequent representations of “the Chinese” as “the other” by even the Old China Hand expats often labeled as “experts” that should know better. I’ve been accused myself, in the past, about this act of carelessly “othering” when talking about China.

Does that mean that we can’t talk about cultural differences or point out problems for fear of offending people (not that!) and being politically incorrect? Of course not! (It had better not.) All it means is that we’re all better off and have a better chance of actually being heard by thoughtful individuals if we try to apply just a little discernment and dial down the blanket statements. (Hint: generalizations that start with “Chinese people” are worth investigating.) If something feels a little too “they’re not like us,” try a more sensitive treatment of the topic. At the very least, you’ll likely get fewer racists agreeing with you in your comment section (how embarrassing!).

20

May 20154 Reasons I Want the Outlier Dictionary of Chinese Characters

There’s a new Kickstarter project related to learning Chinese definitely worthy of more attention: the Outlier Dictionary of Chinese Characters. I’ve had the pleasure of multiple Skype calls with John and Ash of Outlier Linguistic Solutions, and this project is no joke. They’re out to build something I’ve wished has existed for quite a while, and they’ve got the skills and dedication to make it happen.

The Kickstarter page is packed with explanation, so I won’t rehash the same information you can check out on your own. But I will tell you what’s interesting about this project to me.

- It integrates with Pleco. Pleco is already my favorite dictionary, largely because it contains so many different dictionaries. It would be annoying if the Outlier Dictionary were a separate app, and building an app from scratch is a huge drain on resources. So I think this was a smart way to launch the dictionary.

- The Outlier founders are learners turned experts (check out this profile). Sure, no one knows Chinese better than the Chinese, but the perspective of a foreigner that has the passion to devote years and years of his life to it is hugely valuable. They have put a lot of thought into the difference between how native speakers learn Chinese and how foreigners learn Chinese, they’ve deconstructed the process, and they’ve come up with a better way for foreigners to learn characters. We learners need this!

- The dictionary is academically rigorous. Unlike most dictionaries, it doesn’t hold the legendary 说文解字 (Shuowen Jiezi) as the ultimate infallible reference. In fact, research into mistakes made by the Shuowen are part of the dictionary. This is amazing!

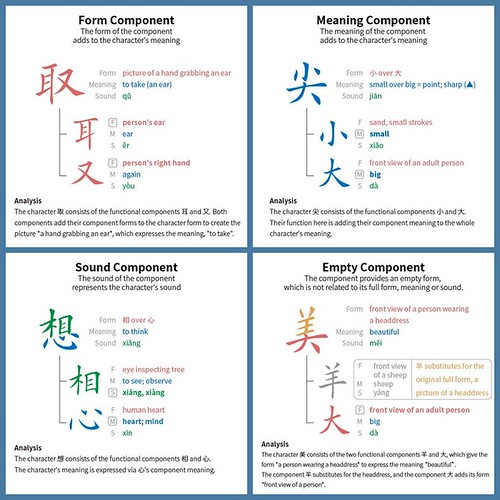

- The approach taken to Chinese character structure is new and necessary. I’ve complained about certain products claiming that radicals are a revolutionary way to learn characters. They’re not. In fact, the term “radical” itself is outmoded and confusing, because it’s tied to outdated dead-tree character dictionaries. So the Outlier Dictionary rightly ditches the term “radical” in favor of “functional component,” and it doesn’t stop there. Check out this breakdown:

OK, but is it too geeky?

One of the concerns I expressed to the Outlier team was that they were building a dictionary for academics that didn’t really serve the practical needs of the average learner. They fervently assured me this was not the case; they are building a dictionary that enables a strong understanding of the system of functional components behind characters, while also enabling curious learners to go as deep as they want in their character studies. This is exactly how it should be done, so I can’t wait to get my hands on this dictionary. I also plan to keep working with the Outlier team and deepen my involvement in their project. I know that clients of AllSet Learning could really use what Outlier is developing.

I’m embedding a demo video at the bottom, but there is a ton of information on the Kickstart page, so check it out!

Outlier Linguistic Solutions — Demo Walkthrough from Outlier Linguistic Solutions on Vimeo.

14

May 2015Far and Near, Black Eyes, and Gu Cheng

Former AllSet Learning intern Parry recently shared this Chinese poem with me. It amazed me with its simplicity. This is a poem that even an elementary learner can get.

The poem [via Baidu Baike]:

> 远和近

你,

一会看我,

一会看云。

我觉得,

你看我时很远,

你看云时很近。

——顾城

Here it is in pinyin:

> Yuǎn hé Jìn

> Nǐ,

> yīhuī kàn wǒ,

> yīhuī kàn yún.

> Wǒ juéde,

> nǐ kàn wǒ shí hěn yuǎn,

> nǐ kàn yún shí hěn jìn.

——Gù Chéng

And in English translation [also via Baidu Baike]:

> Far and Near

> You,

> you look at me one moment

> and at clouds the next.

> I feel

> when you’re looking at me, you’re far away,

> but when you’re looking at the clouds, how could we be nearer!

> translated by Gordon T. Osing and De-An Wu Swihart.

The only potentially challenging aspects for a learner (armed with a dictionary tool) are:

1. Use of 一会 (also written as 一会儿), meaning “for a moment,” which is often pronounced “yíhuì” or “yíhuìer” (make sure that you know your tone change rules!)

2. Use of 时 (shí), a more formal equivalent of 的时候 (de shíhou)

I’m going to have to look into Gu Cheng more. He also has this great 2-line poem (taken from the Wikipedia article just linked to), which is basically at the intermediate level:

> 黑夜给了我黑色的眼睛

> 我却用它寻找光明

Pinyin:

> Hēiyè gěi le wǒ hēisè de yǎnjing

> Wǒ què yòng tā xúnzhǎo guāngmíng

English translation:

> The dark night gave me black eyes,

> I use them nonetheless seeking for the light.

There are a few words in there that would definitely need to be looked up by an intermediate learner, but the only challenging grammatical point is the use of 却 (què).

It’s so great to have material like this accessible to learners.

12

May 2015“C” is for “Women”

Here’s a little puzzle for you. Why is this women’s restroom labeled with the letter “C”?

Here’s another clue: the men’s room is labeled with the letter “W”.

It took me a few minutes to work this out, but eventually I solved it. It’s like this:

1. Men’s and women’s rooms in China, when the traditional “男” for “men” and “女” for “women” are abandoned for a more international feel, are often labeled simply with a letter “M” for “men” and a letter “W” for “women”.

2. Someone noticed this, but only remembered the “W” (and not what it stood for).

3. That same person knew that restrooms in China are often called “WC” (there’s even a hand gesture for it), and assumed that that’s where the “W” came from.

4. The letters “W” and “C” were arbitrarily assigned to the men’s and women’s rooms.

It makes me wonder if all the international quirkiness around us in China has a similarly comprehensible explanation.

07

May 2015Roofies, Counterfeit Money, and Firearms

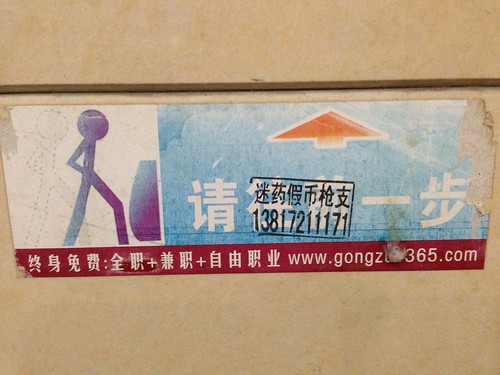

I’m used to seeing ads for fake IDs everywhere in China (sometimes as a stamp, sometimes just written in permanent black marker, nothing more than the word 办证 and a phone number), but I was surprised by this ad. I encountered it in a public restroom near Mogan Shan (莫干山):

The ad is the black stamp on the “step closer to the urinal” PSA, and it’s selling three things:

– 迷药 (something like roofies)

– 假币 (counterfeit money)

– 枪支 (firearms)

All of these, obviously, are highly illegal in China. I’m not sure how such a brazen method of advertising illegal goods can be pulled off (even outside the big city).

01

May 2015May Day Word Play

Today is May 1st, China’s International Workers’ Day holiday. Yesterday I saw this amusing little joke, posted by a former student, “Monica.” The humor is based on transliteration. First the joke, then I’ll follow up with a translation and explanation.

> 小时侯上学,把“English”读为

> “应给利息”的同学当了银行行长,

> 读为“阴沟里洗”的成了小菜贩子,

> 读为“因果联系”的成了哲学家,

> 读为“硬改历史”的成了政治家,

> 读为“英国里去”的成了海外华侨。

> 而我,不小心读成了“应该累死”,

> 结果成了一名光荣的劳动者……工作辛苦了,

> 提前祝大家五一节快乐!

Translation:

> When I was in primary school, the kids that pronounced the word “English”

> as “yīng gěi lìxī” became bankers,

> as “yīngōu lǐ xǐ” became vegetable vendors,

> as “yīn-guǒ liánxì” became philosophers,

> as “yìng gǎi lìshǐ” became politicians,

> as “Yīngguó lǐ qù” became overseas Chinese.

> As for me, I accidentally pronounced it “yīnggāi lèisǐ,”

> and as a result became a glorious laborer….

> You’ve all been working hard; I wish you an early May 1st Labor Day!

For this to make sense, you have to read each individual character that makes up each transliteration (phonetic approximations of the word “English”). Here’s a quick gloss:

Photo by IamNotUnique

– 应给利息: “should, give, interest”

– 阴沟里洗: “sewer, in, wash”

– 因果联系: “cause-effect, connection”

– 硬改历史: “hard/insist on, change, history”

– 英国里去: “England, in, go”

– 应该累死: “should, dead-tired”

(The “washing in the sewer” one refers to washing vegetables in less-than-clean water, rather than bathing, I think.)

Chinese people with limited English ability really do pronounce the word “English” as something like “ying-ge-li-xi,” which makes the joke all the better.

A note to learners: please remember that pinyin “x” should not be pronounced like English “sh.”

22

Apr 2015Holla as “Ni Hao”

I was amused by this translation of 你好 (“hello”) as “holla“:

I’ve been annoyed in the past by how 你好 is almost exclusively translated as “hello” when “hi” or “hey” would serve better in many contexts. In fact, long ago, when I taught English in Hangzhou, I forced my students to stop using “hello” all the time and start using “hi” and “hey” to be more natural in informal situations.

Still, “holla??” Seems like a translator was bored and trying to amuse himself.

Although this does raise another interesting question: how would one most faithfully translate “holla” into Chinese (dialect allowed)?

16

Apr 2015Chinese Gothic

There are tons of gated communities on the outskirts of Shanghai, each offering its own brand of opulence, and frequently with a western aesthetic. One example of this is 马德里洋房, or “Madrid Western Houses.” I can barely make out the English name in the image below, but I think maybe it reads “Palacio de Madrid”? Considering that most Chinese don’t read Spanish, this name is pushing for new heights in pretentiousness.

Rather than apartments, or 公寓 (where most Chinese live), this community offers stand-alone houses with small yards. These are generally referred to as 别墅 in Chinese (a word frequently translated as “villa” in English, but which is often used in Chinese marketing speak to make clear that these are not apartments).

What’s interesting about 马德里洋房 is the Chinese font it uses in its name, which is based on a medieval gothic style:

Sorry the image quality isn’t too good; this is the best I could dig up. Has anyone out there seen any other medieval gothic Chinese?

14

Apr 2015What Linguistic Diversity Feels Like

We often think of “linguistic diversity” referring to the existence of minority languages in an area. But it can also refer to the varying dialects of a region, which in China would include topolects, AKA 方言. When you throw various forms of language together in a single geographical area, they don’t stay distinct; they bleed into each other in interesting ways.

Here are a few anecdotes about that, and what we’re potentially losing when a large region’s language becomes one shade of plain vanilla.

Beijing to Hangzhou

I learned the basics of Mandarin in Hangzhou, where not so many people speak “standard Chinese.” I had to constantly check dictionaries to make sure I was learning the proper pronunciation of new words, because the pinyin sounds “ch/sh/zh” were always being pronounced as “c/s/z”, as southern Chinese tend to do. This was annoying it times, but it didn’t bother me too much, because it was simply the way things were.

Fast forward a few years. I witnessed students of Mandarin visiting Hangzhou from Beijing, absolutely livid because no one in Hangzhou spoke “proper Chinese,” and they couldn’t understand anything. They were used to extremely standard Mandarin, with a bit of Beijing dialect for flavor, but not this.

The whole thing was amusing to me, because not only could I easily understand what they could not, but when I visited Beijing, the locals were so easy to understand that it was surreal, as if every word that came out of every Beijinger’s mouth was a recording from a textbook dialog.

(Note: Americans, when visiting the UK for the first time, may have a similar experience to these students of Chinese in Beijing.)

Fading Tolerance for the Nonstandard

When we had our second baby, we hired a yuesao (post-natal caregiver, 月嫂). We call her Zhang Ayi. Zhang Ayi is great, but she’s from Jiangsu, and she has an accent that can be hard for me to understand.

At first I was thinking, “my Chinese must be worse than I thought,” because after all these years in China, a little accent shouldn’t throw me off too much. It made me feel better, then, to know that my wife (a Shanghai native) also has trouble understanding Zhang Ayi, and fairly often. Zhang Ayi manages to speak in a way that sounds standard, but you just can’t understand it. (As a non-native speaker, it really makes me doubt my listening comprehension!) It’s a different flavor of “nonstandard” than I’m used to, but it affects even a native speaker’s comprehension.

The interesting thing is that my wife’s parents (one from Shanghai, one from Hubei) have no trouble understanding anything Zhang Ayi says. Their generation grew up in a China with wildly heterogenous Mandarin spoken (remember Mao’s Mandarin?), and they just have a much, much higher tolerance for strong accents. This tolerance is fading fast in the younger generations.

Mute Shanghainese

It’s been widely reported that Shanghainese (上海话) is dying. A lot of Shanghainese parents are taking great pains to use Shanghainese with their children to make sure that this cultural heritage does not die out.

The problem is that a dialect/topolect is not merely a family issue; it’s a community issue. And what’s happening with these families is that their children do indeed comprehend Shanghainese, and can usually say a few words and phrases, but they essentially do not speak it. Only standard Chinese is allowed in schools, and that makes it “weird” for Shanghainese kids to talk to each other in anything other than standard Chinese. Shanghainese does not feel necessary or useful to the children.

What’s even worse, even if a Shanghainese parent goes the extra mile and insists that only Shanghainese is spoken in the home, raising her own child to be 100% fluent in Shanghainese, her child will likely be the member of a society where no one else of his generation actually speaks Shanghainese. And one fluent speaker can’t keep Shanghainese going.

02

Apr 2015The Chinese Pronunciation Wiki

For years, I’ve had a few sections on Sinosplice for pronunciation:

– Pronunciation of Mandarin Chinese: Setting the Record Straight

– The Process of Learning Tones

– Mandarin Chinese Tone Pair Drills

(Notably absent: tone change rules)

I’ve also blogged about pronunciation many times, but I didn’t feel like a blog is the best way to organize all this information, and these days I’m putting most of my time into growing AllSet Learning rather than reorganizing Sinosplice.

The Chinese Grammar Wiki has turned out to be a hugely successful experiment, and in about three years has become the internet’s favorite reference for Chinese grammar issues online. Our work is by no means finished there; the Chinese Grammar Wiki continues to grow.

But it’s now time to bring a bunch of scattered information together in the same way we did for grammar, but this time for pronunciation. We’ve started the Chinese Pronunciation Wiki, and it’s still in its early days, but the foundation is strong.

One of the key concepts behind the site which I believe is missing in many current courses and resources with regards to pronunciation is a clear idea of what to focus on, when. Remember: mastery of Chinese pronunciation is a long-term endeavor. Take it step by step.

We’re doing a soft launch of the site this week, and will do a more public launch next week. I’d love to get some early feedback.

A few notes on what we’ve got so far:

– We aim to keep beginner explanations simple, without resorting to linguistic jargon. Full linguistic description for those who want it is part of the longer-term plan.

– Many pages still need to be fleshed out, but for now, the pinyin chart, pinyin quick start guide, tone change rules, and erhua pages are already quite useful

– I’m interested to hear what higher-level learners and native speakers think about our page on Chinese accents (which can be quite a hurdle for learners)

– Images/illustrations are coming

– I have tons of ideas for higher-level pronunciation topics, but we have to cover the basics first

Thank you for your support of the Chinese Pronunciation Wiki, everybody! There will be more news and an official announcement next week.

24

Mar 2015I’m in an Abusive Relationship with Shanghai

Sometimes I feel like I’m in an abusive relationship with Shanghai.

Sure, I love Shanghai, but there are times I wonder if we should be together. Like the times in the winter when I walk outside and I can smell the air (it smells kind of like gunpowder). Or this past winter, when I got a cold that lasted for two months (my worst colds usually last about a week), and my whole family got sick repeatedly (still not better yet).

But then the weather gets nice, and the sky turns blue again, and it’s easy to forget those offenses, or at least put them out of my mind. I remember what made me love Shanghai in the first place, and almost start to believe that cities can change. At least I can be happy now… spring is here. Best to just enjoy it while I can.

17

Mar 2015Being Bilingual Changes Children’s Perception

I recently read a fascinating article called How bilingualism affects children’s beliefs, which details some findings from researchers in developmental psychology at Concordia University in Montreal.

The idea behind the experiment is to see what qualities kids see as innate. Is the language that a person speaks innate, or is it learned? Is the sound that an animal makes innate, or is it learned?

The implications could be quite profound. I quote the final four paragraphs here:

> “Both monolinguals and second language learners showed some errors in their thinking, but each group made different kinds of mistakes. Monolinguals were more likely to think that everything is innate, while bilinguals were more likely to think that everything is learned,” says Byers-Heinlein.

> “Children’s systematic errors are really interesting to psychologists, because they help us understand the process of development. Our results provide a striking demonstration that everyday experience in one domain — language learning — can alter children’s beliefs about a wide range of domains, reducing children’s essentialist biases.”

> The study has important social implications because adults who hold stronger essentialist beliefs are more likely to endorse stereotypes and prejudiced attitudes.

> “Our finding that bilingualism reduces essentialist beliefs raises the possibility that early second language education could be used to promote the acceptance of human social and physical diversity,” says Byers-Heinlein.

I’ve often wondered what would happen to racism in the world if every child born was interracial. The next best thing? If every child is multilingual.

I hope more research is done in this field.

11

Mar 2015The long quest for a fuller explanation of 和 (he)

When I first started learning Chinese in 1998, I learned the word 和 (hé) as a way to express “and.” However, it was an “and” with limitations; it was not to be used to connect sentences or clauses. For example, none of these sentences could be expressed with 和:

– Today we’re going to learn how to hold the pen and learn the stroke order for one character.

– You get a new job, and and I’ll stop living in the treehouse.

– He ran into the street and got hit by a garbage truck.

So the way I learned 和 was as a way of connecting nouns and noun phrases. Not verbs. Different from English, but not too tough, right?

The only problem was that after moving to China in 2000, from time to time I would encounter examples of what were clearly verbs being linked by 和. It didn’t happen often, but often enough to bug me. Worst yet, although some Chinese teachers had told me to only use 和 to connect nouns, others told me 和 could be used to connect verbs too. This conflicting advice was frustrating, and in the end I decided to ignore the non-noun uses of 和 because you don’t need to use 和 for verbs; there are other ways to link verbs.

Fast forward to this year.

The Chinese Grammar Wiki has a beginner-level article on 和 that until very recently stated that 和 is used to connect nouns and noun phrases but not verbs. Then someone on Reddit politely called us out on it with a very good counter-example.

Now that I have a team of Chinese teachers at AllSet Learning, I can have one of my lead teachers properly research the issue. She didn’t find much, and did extensive examination of 和 in use in various corpora. Then we also discussed the issue with a group at a recent teacher training session.

The result is that we now have a new page on advanced uses of 和. It’s still good to start with the basic uses, but more advanced learners can jump into the other messy details.

The bad news is that the issue of when you can and can’t use 和 with verbs is still quite murky. The wiki page needs more examples and more references. (If anyone knows of any research papers or books that touch on this issue, please share! See the Chinese Grammar Wiki page for more details.)

But the good news is that it’s really great to see the Chinese Grammar Wiki expanding in this way, through feedback and the dedication of AllSet Learning’s academic team. It’s not every day you get to see a free resource like this blossom, and it’s even more gratifying to be part of it.

03

Mar 2015Sad Newspaper Recycling Man

Way back in 2008 or so I used to ride the subway regularly to get to “the factory,” the original ChinesePod office. Every day as I got off the subway and exited the station, I’d see these “newspaper recycling people.” They were typically elderly, and they stood by the subway turnstiles, near the garbage cans, busily collecting the used newspapers of all the passengers that were already finished consuming their daily paper-based commute reading. The “newspaper recycling people” accumulated quite a stack of papers every morning.

I don’t ride the subway as much these days, but I noticed recently that these “newspaper recycling people” are still there, but they’re a lot less busy than before. They collect far fewer newspapers these days. I snapped a photo of one, tucking his meager bounty into his bag:

Who needs a newspaper when you have the (censored) sum of the world’s knowledge and entertainment in the palm of your hand? Hopefully these enterprising older people can find a new way to make a few extra kuai.

27

Feb 2015“Correction Brother” is Hilarious

Over the CNY holiday a video of a Shandong guy trying to make a phone call with his in-vehicle voice dial went viral, and it is hilarious:

The guy has an accent, so his tones are a little off, but you can definitely make out the number he’s trying to dial with the help of the subtitles.

The part that reads “X死,” while not polite, is actually not obscene; it’s a Shandong slang term “xie 死” which means the same as “打死” (beat someone to death).

Anyway, this guy has been nicknamed 纠正哥, “Correction Brother,” because he keeps trying to “correct” the system’s misunderstanding of his voice commands.

After the video went viral, he was later interviewed by a reporter:

New information learned from this video:

1. The band-aid on 纠正哥‘s head is because his friend (owner of the number that keeps getting repeated in the first video) cracked him over the head with his phone when he started getting non-stop phone calls after the original video went viral.

2. The friend gave the number and the phone to 纠正哥, which is why he has it, and you can see it getting non-stop calls at the end of the interview video.

3. 纠正哥 got mad because the interviewer guessed he was 45 years old, but he’s only 33.

Thanks to John Guise for bringing this video to my attention, and to Yu Cui for alerting me to the follow-up video and providing Shandong insider knowledge!

25

Feb 2015Linking Breaking Bad to Better Caul Saul through Chinese

Breaking Bad was an awesome drama. Better Call Saul is looking like it’s shaping up to be another great story. But if you’re not already familiar with both series, it’s far from obvious that the two are connected based on their titles alone. Not so with Chinese!

The Chinese titles of the two series are:

And in plain text:

– Breaking Bad 绝命毒师 (Juémìng Dúshī)

– Better Call Saul 绝命律师 (Juémìng Lǜshī)

The two differ by exactly one character!

绝命 (not a common word at all) according to my dictionary means “to kill oneself” (but here, while not entirely clear, must mean something like “at the end of one’s rope”), and 毒师 (also not at all a common word) would be something like “drug master” (which you could translate as “drug lord,” but “drug lord” is more commonly expressed in Mandarin as 毒枭). The word 毒师 was likely chosen because it’s similar to 老师, and Walter White begins the series as a chemistry teacher. Meanwhile, 律师 is actually a common word meaning “lawyer,” however. It seems to be just a fortuitous coincidence that the new series name can play off the old series name so neatly.

Now, you could definitely argue that neither is a good translation of the original English series title, but both “Breaking Bad” and “Better Caul Saul” would be extremely hard to translate well into Chinese. It does seem that keeping consistency of translation to link the two is a nice little added benefit when you can’t very faithfully translate the original titles anyway.

17

Feb 2015Chinese New Year Trumps All Holidays

This Wednesday, February 17, is Ash Wednesday, the Catholic holy day that kicks off Lent. In an interesting turn of events, the church in China made this announcement recently:

> Please also note that China Dioceses grant a dispensation from Fast & Abstinence on Feb. 18 this year because it is the eve of Chinese New Year. We are encouraged to offer acts of charity and other sacrifices instead on Ash Wednesday.

So when a holiday of firecracker-exploding, gut-busting Chinese merriment clashes with a holiday of fasting and quiet reflection, the Chinese holiday is ceded the victory. (Well, on its home turf, anyway.)

I noticed that this past Saturday, Valentine’s Day, there was far fewer promotions, flowers, and chocolates to be seen around Shanghai, compared with last year. I imagine it was because so many people were already preoccupied with trying to get home for the holiday, and most companies didn’t see the point into putting too many resources into selling to an audience that was paying little attention. (Hey, China has a backup Valentine’s Day anyway, so no big deal.)

Chinese New Year trumps all holidays.

Happy Year of the Sheep!

13

Feb 2015Chinese New Year Wishes by Dialect

Photo by Yang and Yun on Flickr

China Simplified‘s blog has a great post on variations of Chinese New Year wishes, all in different regional dialects (AKA fangyan): Spring Festival wishes from around China.

The post has embedded audio for 15 different greetings, covering fangyan from places like Henan, Sichuan, Shandong, Guangdong, Guizhou, Tianjin, Zhejiang and other places.

If you’ve every enjoyed Phonemica, you’ll enjoy this (and it will bring a smile to your Chinese friends’ faces as well).

Happy Chinese New Year! (It’s still 6 days away…)

10

Feb 2015Very Google Translate

These days it’s not uncommon for an English word to get thrown into a Chinese sentence, sometimes with a disregard for the original part of speech. A typical example is “很fashion” (“very fashion,” meaning, “very fashionable“).

One of things things we sometimes do with AllSet Learning clients is give them translation exercises where they have some English sentences, and they have to translate them into Chinese. We make sure that the sentences are practical and not random, so the exercise can be quite fruitful.

Occasionally, though, unwanted technology creeps into the “learning process,” and the teacher notices. This was a comment from one of our teachers on a client’s translation exercises:

> 有几句非常google translate。

“There were a few sentences that were very Google Translate.” Well said.