02

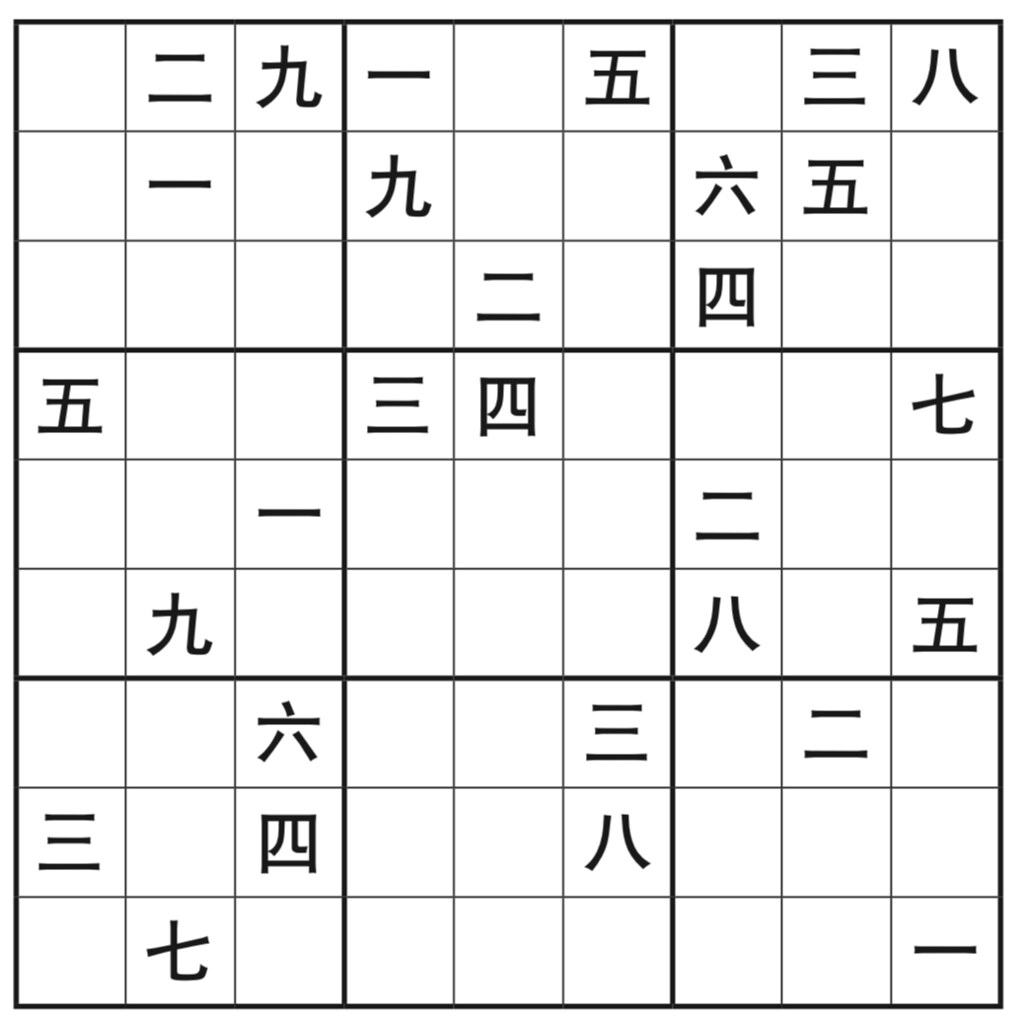

Nov 2021Chinese Number Sudoku

Every now and then I came across an idea that is brilliant in its simplicity. This is one of them: Chinese number sudoku!

So it’s just sudoku (数独 = sudoku = shùdú), but using the Chinese characters numbers 1-9: 一、二、三、四、五、六、七、八、九.

If you want to improve your handwriting in Chinese, it can be hard to come up with a way that isn’t mind-numbingly boring. Well, if you like sudoku, this should do the trick.

(Technically you could do this with any set of 10 characters; they don’t even need to be numbers. I imagine it’s very difficult mentally, to pull off, though, if they’re not in a very clear sequence.)

Anyway, these images come from the book Chinese Sudoku by Earnshaw Books (posted with permission), and it’s also on Amazon.

27

Oct 2021Boozy Latte Brings the Bad Pun

Saw this ad in my neighborhood here in Shanghai:

I’m of the opinion that this quite a bad pun. My Chinese friends and co-workers agreed. The text that the ad copy sounds kinda like is;

我就爱这样

In other words, “i just love this.” The ad also “subtly” communicates with the “酒” that there’s alcohol in there, while broadcasting that they’re going after the “young” demographic as well.

The thing is, this latte drink contains no alcohol… it’s just 酒香 (alcohol-scented). Maybe that’s kinda like the fake rum in rum raisin ice cream? I dunno.

I’m not buying any of this on any level! (Oh, and this is the same robot coffee that I’ve blogged about before.)

21

Oct 2021When a Window is a Door

What’s the old saying? “When God shuts a door, He opens a window?” Not sure if that applies here, but this is the “door” of a small clothing shop here in Shanghai:

That’s right, you step on the little footstool and climb in through the window. There is no other door that customers have access to.

Shops like this used to have their storefronts on the street, spilling out onto the sidewalk. These were the charming little local shopping options that China is known for. But in recent years, the government has been closing many shops like that, and even bricking up patios that used to be used to (technically illegally) sell stuff.

But bricking up a storefront doesn’t always mean that you can’t sell stuff at all. As you can see.

P.S. This is not a new phenomenon. I just haven’t commented on it before, and happened to snap this photo the other day.

14

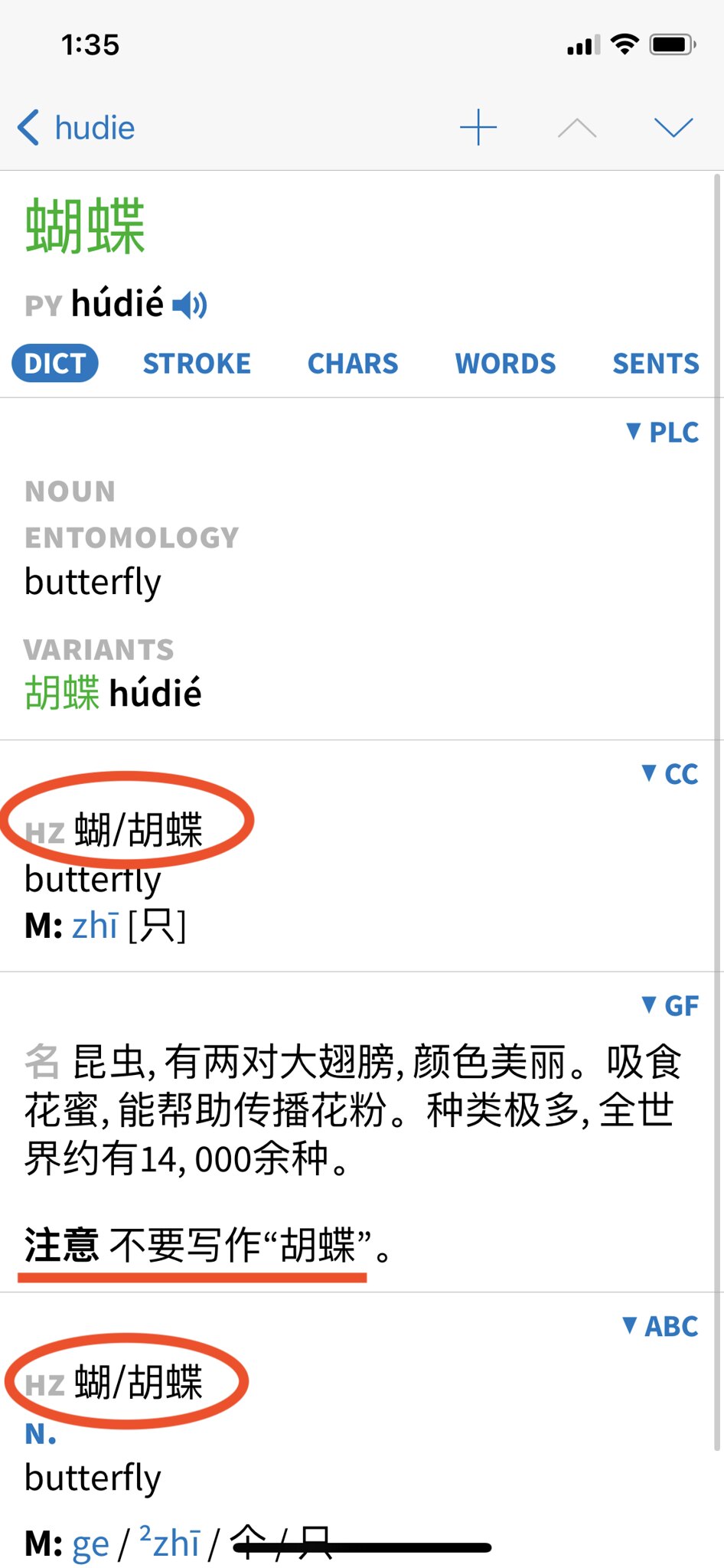

Oct 2021Bickering Butterflies in Pleco

Most learners of Chinese know about Pleco, the popular Chinese dictionary. One of its great features (especially for long-term serious learners of Chinese) is that you can have multiple dictionaries within Pleco. This can provide wider coverage and a lot more depth. But every now and then, this feature can potentially be the source of confusion.

Check out this Pleco entry for “butterfly” (蝴蝶):

Confused? It’s like the dictionaries are arguing amongst themselves.

PLC: It’s 蝴蝶.

CC: Actually, both 蝴蝶 and 胡蝶 are OK.

GF: DO NOT WRITE 胡蝶!!!

ABC: Whatevs. You can write 蝴蝶 or 胡蝶.

My Chinese co-workers say that 胡蝶 can be a woman’s name, but not a butterfly. Not sure what the source of contention is here. (If you know, feel free to share in the comments!)

08

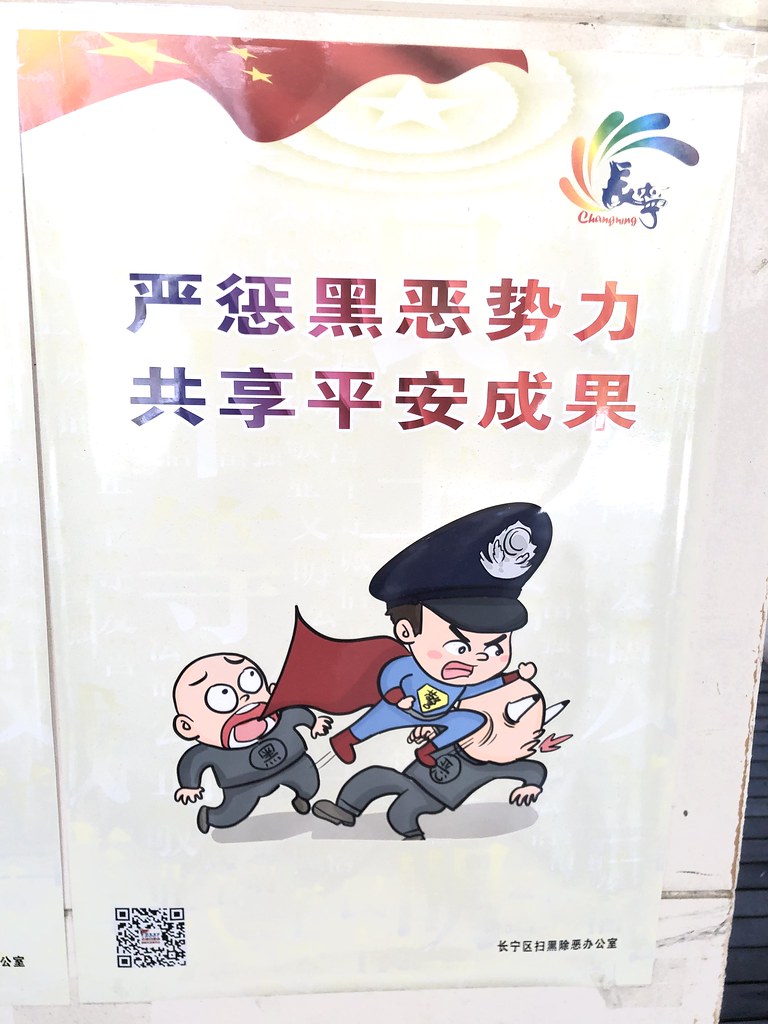

Oct 2021The Fruits of Peace: IN YOUR FACE!

This propaganda poster cracks me up every time I see it around Shanghai:

The Chinese reads:

严惩黑恶势力 (Yánchéng hēi‘è shìlì) Severely punish evil power

共享平安成果 (Gòngxiǎng píng’ān chéngguǒ) Share the fruits of peace

OK, so I’m not really trying to make that propaganda sound less ridiculous in English, but look at that picture. That’s “super police” (his chest has a 警 in it for 警察, “police”). This is “sharing the fruits of peace”?

I have to chuckle, wondering if the copy writer had any clue what the illustration would be like.

28

Sep 2021The Garlic Hangover

After a Saturday night of delicious Mongolian hot pot (涮羊肉) particularly heavy on the garlic, I had that familiar feeling when I woke up in the morning: my whole mouth reeked of garlic, and even my tongue itself felt and tasted like a marinated chunk of garlicky meat. This stubborn garlic imprint took over 24 hours to fade. (And yes, I brushed my teeth. Multiple times. That gave me minty garlic breath.)

The thought came to me: this is a garlic hangover. But I was not the first one to come up with this term… it’s already in Urban Dictionary.

How common are these garlic hangovers for my garlic-loving friends in other countries? I don’t know, but in China it’s especially common when you eat hot pot (火锅) or the variation of hot pot known as Mongolian hot pot (涮羊肉). It’s because you “mix your own sauce,” and you’re given free reign to liberally dump the minced garlic (蒜泥) into your sauce bowl. And liberally dump I do!

Here’s what the minced garlic looks like (but usually there’s more of it):

Then when you mix your sauce, it might look something like this (although mine is typically more of a brown/red spicy color):

So then you’re dousing meat and veggies in that sauce all meal. And if you’re anything like me, you’ll need to whip up another bowl of sauce halfway through the meal.

Finally, for those unclear, I’ll share a picture of Mongolian hot pot (the bundt cake of hot pots):

(Note the sauces hiding “innocently” in the back. Don’t be fooled!)

16

Sep 2021Movie Titles in Chinese: Translations or Labels?

I enjoy examining the translations of brand names, book titles, and movie titles. They’re important for many reasons, so quite a bit of thought should have gone into their selection. Indeed, many translations of this kind are brilliant and well worth studying. One glaring exception, though, are the names of many Hollywood movies released in Mainland China.

I’ve mentioned before that American animated films in China have some of the “laziest translations ever,” blatantly overusing the words 总动员 and 疯狂. In this article I want to talk about another phenomenon: 玩家 (literally, “player”). This one is not nearly as overused, but it’s conspicuous for several reasons.

Free Guy: 失控玩家

The movie title I’m focused on here is the Chinese translation of the new Ryan Reynolds movie, Free Guy. In Chinese, the name is 失控玩家, which is literally something like “player out of control.” (WARNING: my analysis may involve very mild spoilers (but nothing that spoils the ending.)

If you know anything about this movie, you know that it’s about an NPC (non-playable character) in an online game who becomes self-aware and “goes rogue.”

Here’s the thing: an NPC is, by definition, not a player. A character that is non-playable is not a player. That’s kind of the point, and this point does drive the plot in some places. So while “失控NPC” (“out of control NPC”) would be appropriate, 失控玩家 is not. This may seem like nitpicking, but it’s not a minor issue if you’re a professional tasked with titling the movie. It’s almost as if the “translators” for the movie title never watched the movie and just took a guess as to what it was about. (?!?!)

Now there are “players” in the story that play an important role in the plot. But these players are not 失控玩家. The only other character in the story that could be said to 失控 (lose control) would be the founders of businesses or games that lose control of their “creations” during the story. But in those roles, they’re not “players” either.

Interestingly, the Taiwanese name for the movie is different but essentially makes the same error:

脱稿, in this case, means “to go off script.” So, again… it’s the NPC going off script, not a player.

Why the 玩家?

So the question is: why force the use of 玩家? What’s the end here?

It does make me think of another movie that was fairly popular at the Chinese box office in recent years. Ready Player One‘s Chinese “translation” is 头号玩家.

Although not as severe, this movie title has its own translation accuracy issues. First of all, 头号玩家 means “number one” in the sense of “best.” So it doesn’t mean “Player #1”; it means “the best player.” The text “ready player 1,” which displayed on the screen before player 1’s turn to play a game, may not be as familiar to a Chinese audience, since many Chinese kids grew up playing on pirated gaming systems that were in other languages, and modern gaming systems don’t tend to use the “take turns playing” mechanic anymore. So there may be no way to translate “ready player one” that would be familiar to a Chinese audience like “ready player one” is to a video game-loving American audience. Given that context, the translation choice makes more sense.

Crucially, though, the word “player” is in there. 玩家.

A co-worker pointed out to me that around the same time, a Chinese movie called 幕后玩家 (literally, “player behind the scenes”).

Related? Uncertain.

Movie Title Keywords as Labels?

So this got me thinking about the “translation trends” we’re seeing here in China. Could it be that rather than just being “lazy” or bad,” the higher-ups in charge of the translation selection are opting for purely functional titles that don’t consider translation fidelity a priority? The idea is that when you add in 总动员 or 疯狂, you’re communicating to the market very clearly: this movie is a cartoon for kids. When you include 玩家, maybe it’s something like, this is an action movie related to video games?

It seems incredibly patronizing to the Chinese audience. This audience is clearly sophisticated enough to learn what a movie is about and make a decision on whether to buy a ticket or not, without the aid of a “movie title keyword,” right?? One would think so.

It’s worth noting that plenty of movie title translations in China don’t follow this trend, such as all of the Marvel movies. But the Marvel brand can sell tickets on its own. The “movie title keyword” approach seems to be a card that’s played when a one-off movie with no connection to known franchises appears.

Will this bank of “movie title translation keywords” continue to grow? Time will tell.

12

Sep 2021Migrating to a New Webhost

No time for blogging this past week, as I’ve been busy migrating my websites away from Webfaction. I’ve really enjoyed using that webhost over the years, but they’ve since been acquired by the vile behemoth GoDaddy.

So now I’m migrating to a new little upstart company very much like the old Webfaction called Opalstack. Seems like a great company so far.

This is my last post out of Webfaction. Blogging to resume shortly from Opalstack…

02

Sep 2021Key Word of the Month: jianfu

I’m hearing the word 减负 (jiǎn fù) nonstop these days. Of course, it’s largely because I’m a parent with two kids in the Shanghai primary school system, but it’s still a big topic with huge implications for all of Chinese society.

减负 (jiǎn fù) is actually short for 减轻负担 (jiǎnqīng fùdān), literally, “lighten the burden.” It refers to students’ burden of schoolwork. You sometimes hear the term 双减 (shuāng jiǎn), literally, “double reduction,” because recent policies reduce both students’ homework and their after-school extra-curricular studies.

Major Changes in Education

Last month a new law suddenly greatly limited what extra-curricular classes in math, Chinese, and English were allowed to be offered by private companies. These topics are now to be covered solely by the school system.

Yesterday the school semester started, and elementary students’ homework has been drastically reduced, supposedly to 30 minutes or less. First and second graders should have no homework at all.

Is this possible? Is this even China??

Already I’m seeing some interesting responses:

- My daughter came home yesterday with instructions from her teacher for the parents, telling us to be sure to fill out “0-30 minutes” as the amount of homework she did in the official questionnaire all parents have to do daily through WeChat.

- On day one of the new semester, there is already talk in the classroom about students not having to take final exams this semester, if they get high enough grades. But can they even get high enough grades with so little homework? Is there subtle hinting going on here?

Why?

It would be nice if the only reason this was being done was the well-being of the students. But of course there are other motivations.

The main motivation I keep hearing is to encourage the population to have more children. Simply changing from a One Child Policy to a Two Child Policy (and then a Three Child Policy) does not achieve the desired results anywhere near quickly enough, and the population is aging rapidly. More has to be done to reduce the social momentum of the One Child Policy.

The cost of education is one of the major reasons it’s so expensive to raise a child in China, but if all the extracurricular class costs are cut out, the financial burden on parents is drastically reduced. At the same time, the parents’ burden to hound their children every day, all evening to finish homework is also drastically reduced.

Of course there are other theories… theories which some parents I talk to have labeled “conspiracy theories.” Stuff like reducing dependence on outside sources of education also reduces exposure to non-Chinese, non-party-approved channels of information. It’s a step closer to total control of the education system (and thus the minds of the new generation). Crazy?? Hmmm…

25

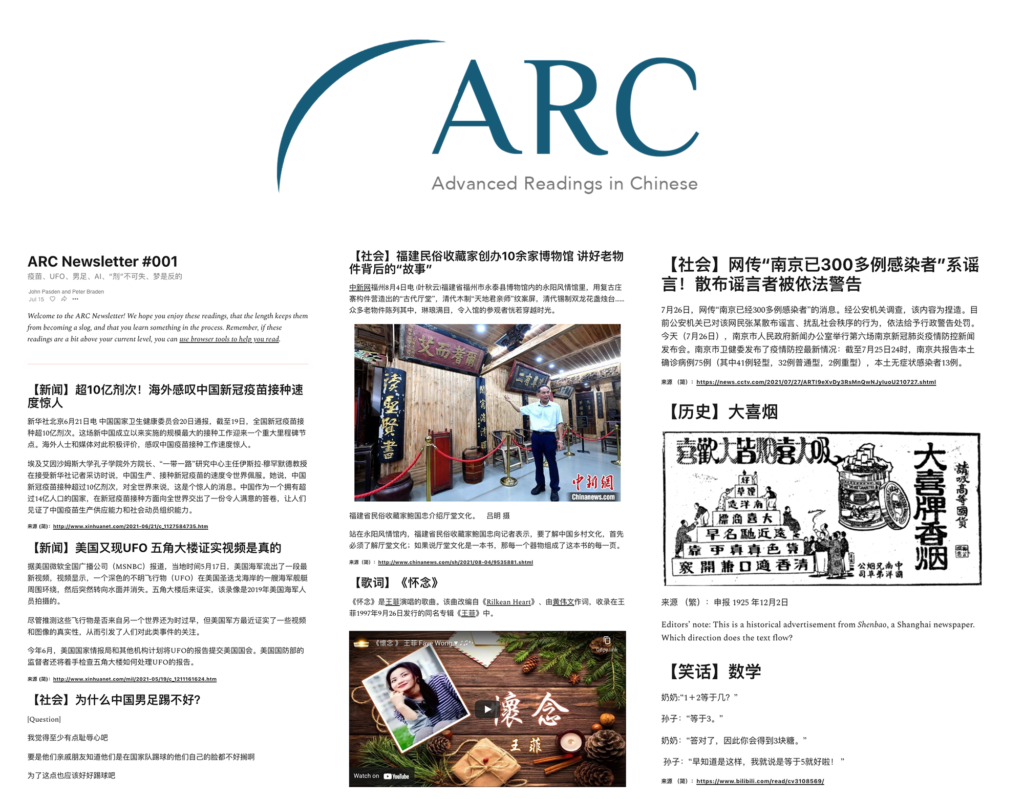

Aug 2021Just Launched ARC (Advanced Readings in Chinese)

Here’s a quick summary from the AllSet Learning blog post:

Each newsletter consists of roughly 5 short pieces (excerpts of longer articles, which are cited and linked). The 5 pieces typically consist of:

- a news item

- a “social trends” item (less time-sensitive, more focused on modern China and “the buzz” currently en vogue)

- a visual piece

- an alternative piece related to art, poetry, music, propaganda, or something else

- a joke

(If this stuff reminds you a little bit of Reader’s Digest, or the Chinese version 读者 (Dúzhě), you’re not crazy! There was definitely some inspiration drawn from those.)

Advanced learners, head on over to the Substack ARC newsletter page and check it out!

18

Aug 2021Emergency Toilets (Guilin)

Spotted this sign in Guilin:

This is not Chinglish. This is not bad translation. This has got to just be someone’s idea of a joke.

What the Chinese actually says is:

应急避难所 (yìngjí bìnànsuǒ) emergency shelter / place of refuge in an emergency

I feel a little bad for the foreigner sprinting for a toilet like the guy on the sign, and unable to find one in time…

(It is kind of funny, though!)

13

Aug 2021The Storefront Brainstorming Gimmick

I snapped this photo in Shanghai under a light rail line:

So it’s an empty storefront with the following text plastered across it:

失业了! [Lost my job!]

租了个店! [Rented a storefront!]

不知道做什么! [Don’t know what to do!]

你们想吃啥! [What do you guys want to eat?]

留言告诉我! [Leave me a comment and tell me!]

一经采纳,红包奖励! [If your idea is used, cash reward!]

快扫码上车,挺急的! [Get on board quick, it’s urgent!]

给我扫! [Scan me!]

迷茫 [Perplexed]

It’s fairly obvious that it’s not a random person’s idea; it’s a company’s promotional gimmick.

I didn’t scan the QR code, but it’s fun to see stuff like this.

11

Aug 2021The Chinese Government’s Forgettable COVID Slogans

The Chinese government has been big on slogans for quite a while, and when it goes all out, you see those things everywhere. Perhaps it is starting to feel like the “era of slogans” is over, but these red banners no longer feel as effective as they once did.

I noticed this one the other day next to a bus stop here in Shanghai:

It’s hard to translate (I know, the second one is laughably bad), but it would be something like this:

坚持“防疫三件套”、“防护五还要”

(Jiānchí “fángyì sān jiàn tào”, “fánghù wǔ háiyào”)

Persist in the “set of three virus preventions” and the “five protective ‘still gotta'”

When I asked Chinese friends and co-workers about the slogan, no one could name the “set of three virus preventions” or the “still gotta” things you’re supposed to do, but they could guess.

When I asked about the effectiveness of such a slogan, I got a very noncommittal, “well, it rhymes….”

防疫三件套 (fángyì sān jiàn tào)

I found these on a government website:

The word 套 means “set.” The idea is that these three measures form a core set.

- 佩戴口罩 [wear a face mask]

- 社交距离 [social distancing]

- 个人卫生 [personal hygiene]

(Kind of funny that they used the WeChat app icon for #2!)

防护五还要 (fánghù wǔ háiyào)

I found these on the same government website:

So the idea behind the 还要s is that you still need to do these things (even though you’ve been doing them for almost two years now).

Here’s the Chinese text, to which I’ll add a few simple notes:

- 口罩还要继续戴 [masks]

- 社交距离还要留 [social distancing]

- 咳嗽喷嚏还要遮 [cover mouth when coughing or sneezing]

- 双手还要经常洗 [wash hands]

- 窗户还要尽量开 [open windows]

Note that each line always uses the exact same number of characters. That’s a slogan thing.

Masks and Social Distancing

I’ve noticed in Shanghai that people are very good about wearing masks, but not so good about social distancing. Clearly the government is trying to enforce both of these (both of these appear in both lists above), with social distancing officially encouraged by marks for where to stand when waiting in line, etc., but these social distancing queues seem largely ignored, with a few exceptions.

It definitely feels like the government’s best tool for enforcing social distancing is simply forcibly shutting down social activities, such as classes, meetings, etc. (Church services have once again been canceled in Shanghai, since last week.)

04

Aug 2021Back to Yangshuo

It’s hard to believe that it’s been 19 years since I was last in Yangshuo (near Guilin). I spent 4 days there with fellow English teachers from Hangzhou Wilson and Simon. We paid 100 RMB per night for our hotel.

This time was a family trip. I was there all last week. Our hotel room was a bit more expensive (although still reasonable), and definitely nicer. It was a very different travel experience, and due to the time lapse, you could say it was a wholly different destination. I recognized literally one place from my previous visit in 2002. It was a bridge.

One thing that was consistent is that this time, too, the trip was all about outdoor activity and natural scenery. We explored two different caves, hiked to an amazing waterfall for a cool swim, spent an afternoon scrambling over rocks on a river trek, and just non-stop enjoyed that gorgeous Guangxi mountain scenery you see everywhere you go. Recommended (still, after 19 years)!

Also, if you’re looking for a guide for hiking, caving, or rock climbing, 蓝天攀岩 was quite good, and reasonably priced. We found them on Taobao.

I won’t share my family photos, but you can see the pics from 2002 on Flickr (and the mountains haven’t changed).

16

Jul 2021Chef’s Hat Characterplay

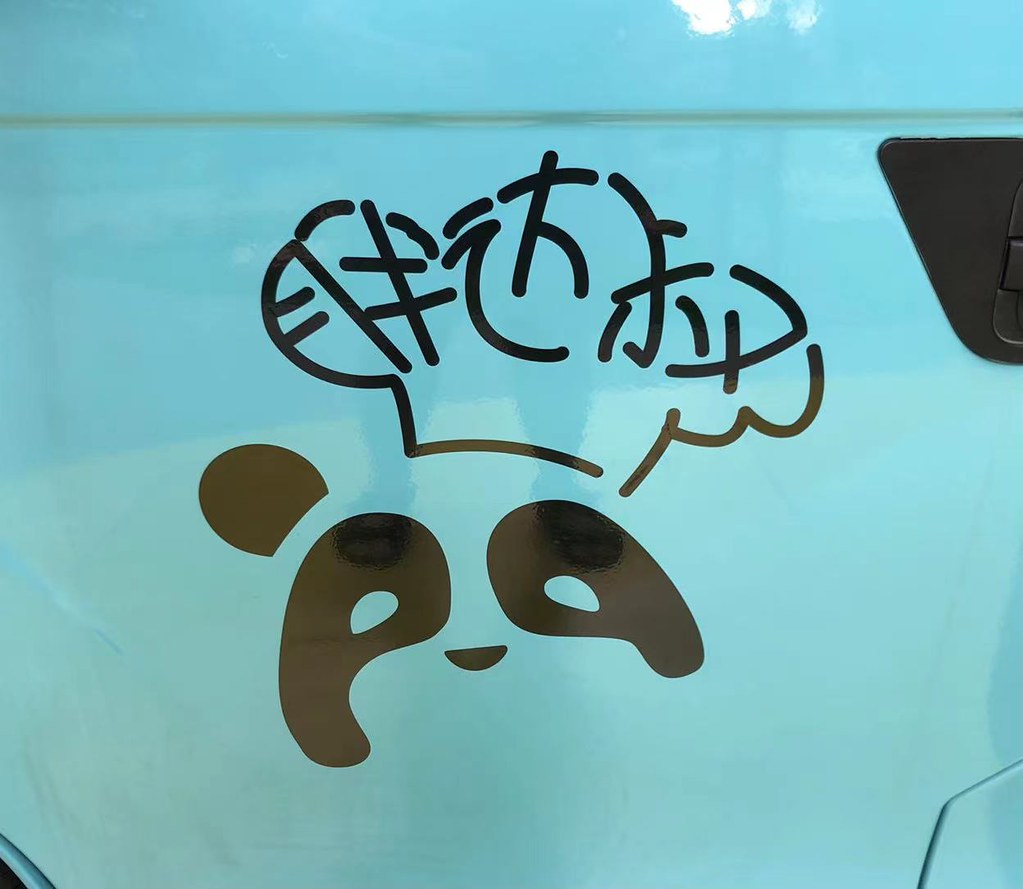

I took this photo here in Shanghai:

Check out that logo:

Believe it or not, there are three characters in there! You might need to be advanced to make them out. Can you read them?

I let my coworkers (native speakers of Chinese, and also Chinese teachers) see this logo, and of course they could read it when they focused on it, but it took them a full second to make out those characters.

SPOILER ALERT!

The answer is below:

胖达叔 (Pàngdá Shū)

Uncle Panda

Notes:

- 胖达 (pàngdá) is just a phonetic representation of “panda” in Chinese, and uses the word “fat” (胖) so that it feels both semantically appropriate and cute.

- 叔叔 (shūshu) means “uncle,” but is sometimes shortened to one character, as in this case. (I wouldn’t recommend trying it on your own, though, with people you’re trying to be respectful toward! Stick with 叔叔 for those people.)

Since this logo uses actual characters, it perhaps doesn’t fit my usual definition of “characterplay” (where new characters are created), but close enough! For more characterplay (much of it easier), see the Sinosplice characterplay tag archive page.

09

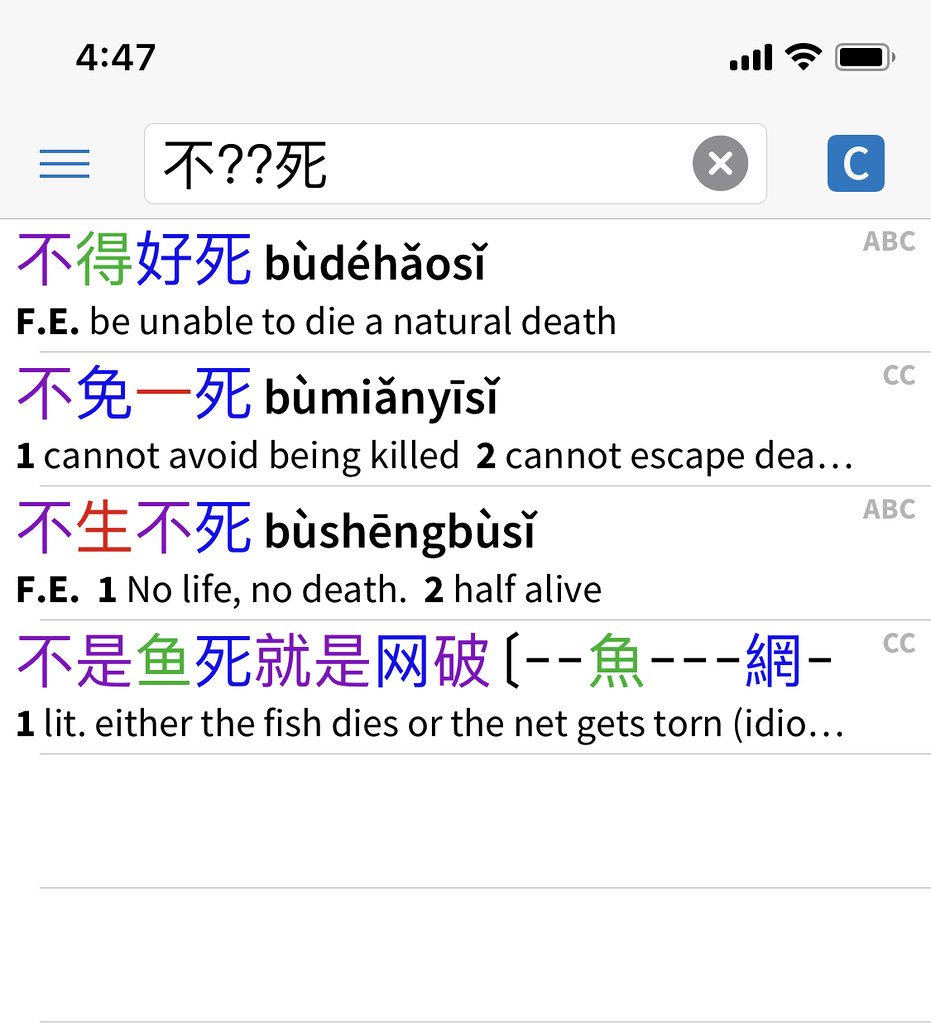

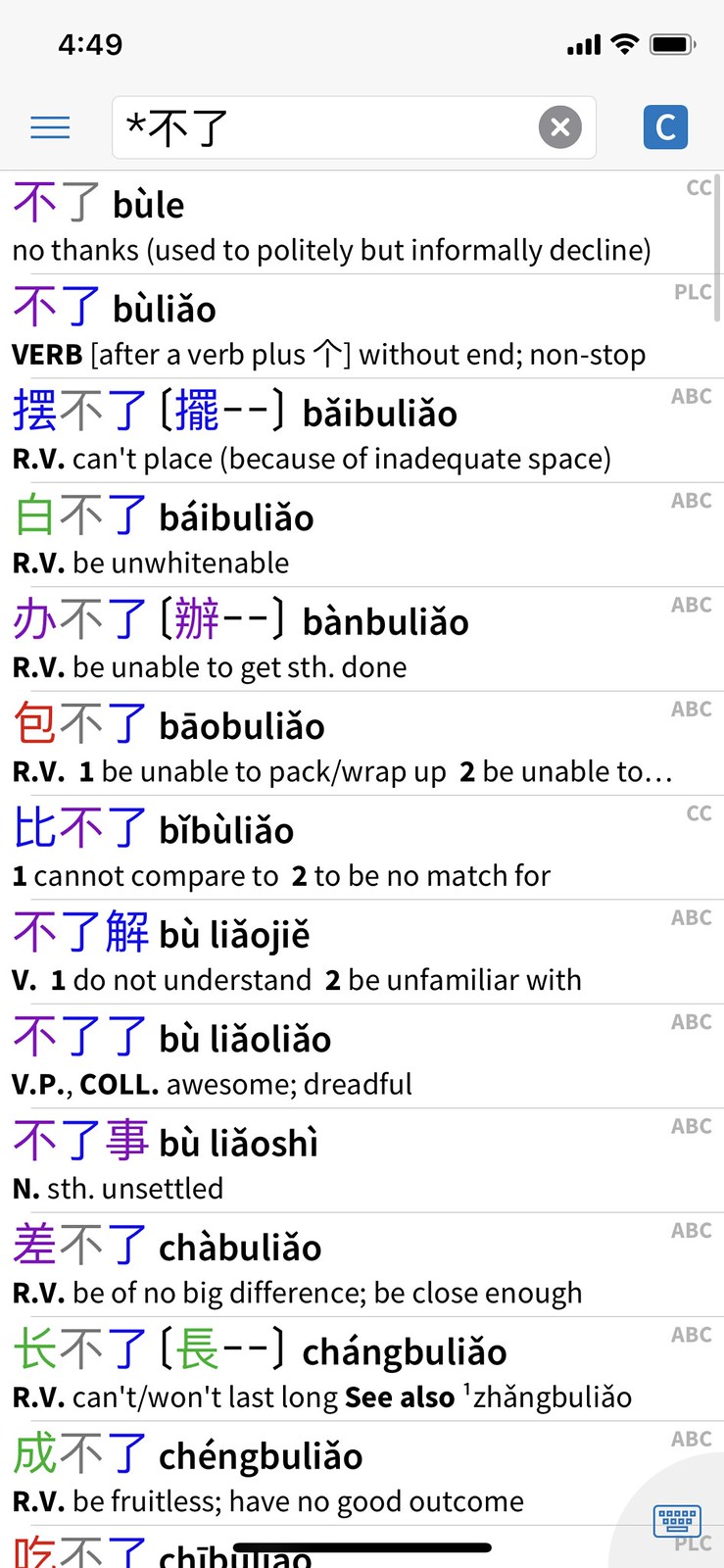

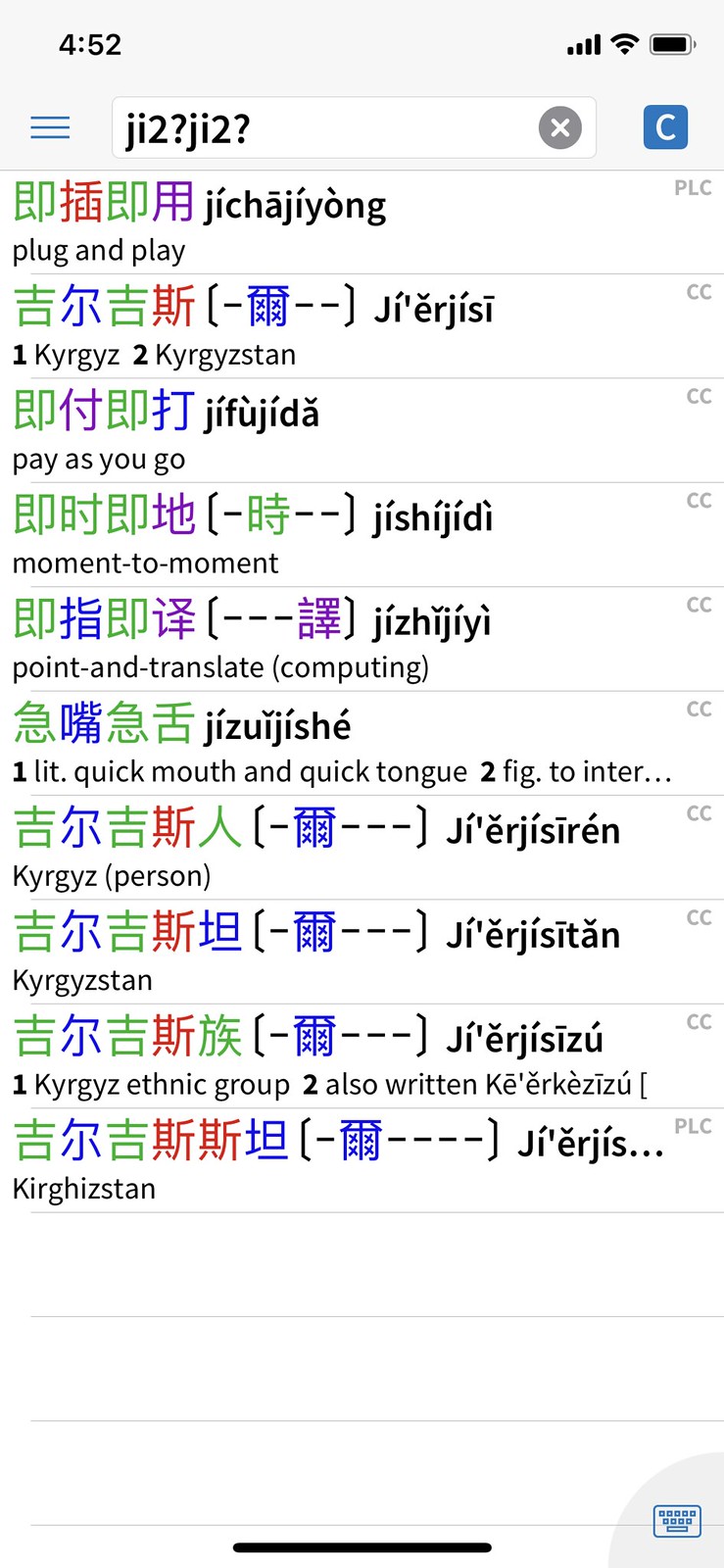

Jul 2021Searching Pleco Dictionary Entries with Wildcards

Wildcard search is one of Pleco’s super useful features that a lot of people don’t know about. I want to share not only how to do it, but also some actual use cases (otherwise you might never remember to use it when the time comes).

Pleco’s Wildcard Characters

In case you’re not aware, “wildcard characters” in computing are characters that can stand for anything, kind of like variables. They’re frequently used in search. It’s like how the joker can be used to substitute for any card in many card games.

When you’re searching a dictionary in Pleco, there are two wildcard characters you can use:

- “

*” (asterisk: can match any number of Chinese characters, including zero) - “

?” (“at” sign: will match exactly one Chinese character, and not zero)

If this isn’t clear enough, the examples below should clear everything up. (Otherwise, you can check out Pleco’s own documentation.)

Use Case 1: What was that 成语??

Most chengyu (成语) are 4 characters. Eventually you’ll find yourself having to learn a lot of them, and recalling just the right one when you need it can be difficult. This is the perfect scenario for the “?” wildcard character, when you know there are 4 characters in the entry you’re looking for.

Here are some examples:

(That last one showed up in the search results because the search term matched exactly a part of a longer entry. This is kind of rare in longer search terms, and it’s not a problem.)

Use Case 2: Gimme more like that!

Another great use case is discovering patterns and using those to learn new words and phrases. For example, numbers in chengyu. You might learn 一心一意 and then want to find more examples of “一……一……”. Perfect! Just search: “一?一?“. Results:

In this case, you’d want to use the character 一 and not the pinyin “yi.” You can see the difference:

Another good example is the 丢三落四 pattern: “……三……四”. Search: “?三?四“. Results:

This way of searching is not just for chengyu, of course. Maybe you just learned the result complement ~不了. Since there are tons of examples of this pattern in Pleco, both as entries and in examples sentences, the search “*不了” turns up quite a lot:

You might also try searching for the complement in one-character and two-character verb combos separately, by doing the searches “?不了” and “??不了” separately.

Use Case 3: “jì ~ jì ~”

This one relates directly to my recent article titled Shanghai Urges Residents to Get Vaccinated… via Megaphone! (audio). In that one, I mentioned that the speakers in two of the audio files mispronounce the word 即 as “jì” (fourth tone) when it should be “jí” (second tone).

But how could I be sure? If there’s one thing that learning Chinese all of these years has taught me, it’s that humility is always warranted. So before I can be too sure about a statement like that, I search dictionaries and check with native speakers, too. Below is how I used wildcards to check Pleco for the pattern.

First, if I’m lazy, I might just search for “ji*ji*” (no quotes). This does not yield good results:

Then, I might reason that searching for 4-character patterns makes more sense. So I search this: “ji?ji?” (no quotes). Results:

Again, not great. Lots of noise. Well, I can also mix in pinyin with tones to get more precise. I can search for both “ji2?ji2?” and “ji4?ji4?“. This gets me:

Finally, if I suspect that 即 (second tone) and 既 (fourth tone) are the most likely candidates, I can search specifically for those: “即?即?” and “既?既?” (I’ll spare you those screenshots). Those results, combined with with native speaker feedback, allowed me to be confident in my assertion that the speakers meant “jí” (即, second tone), even though they said “jì” (fourth tone).

Experiment! It’s easy and a fun way to discover new words, since no one flips through paper dictionaries anymore….

01

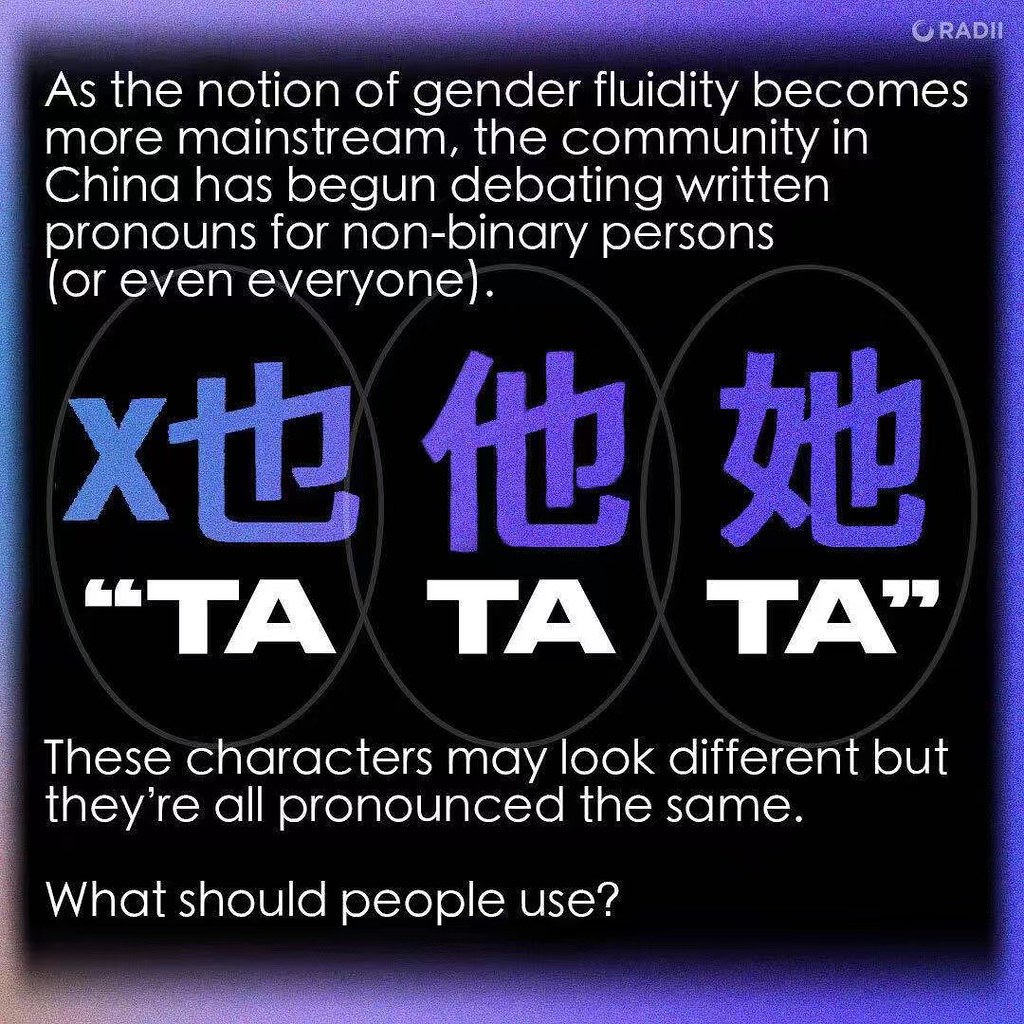

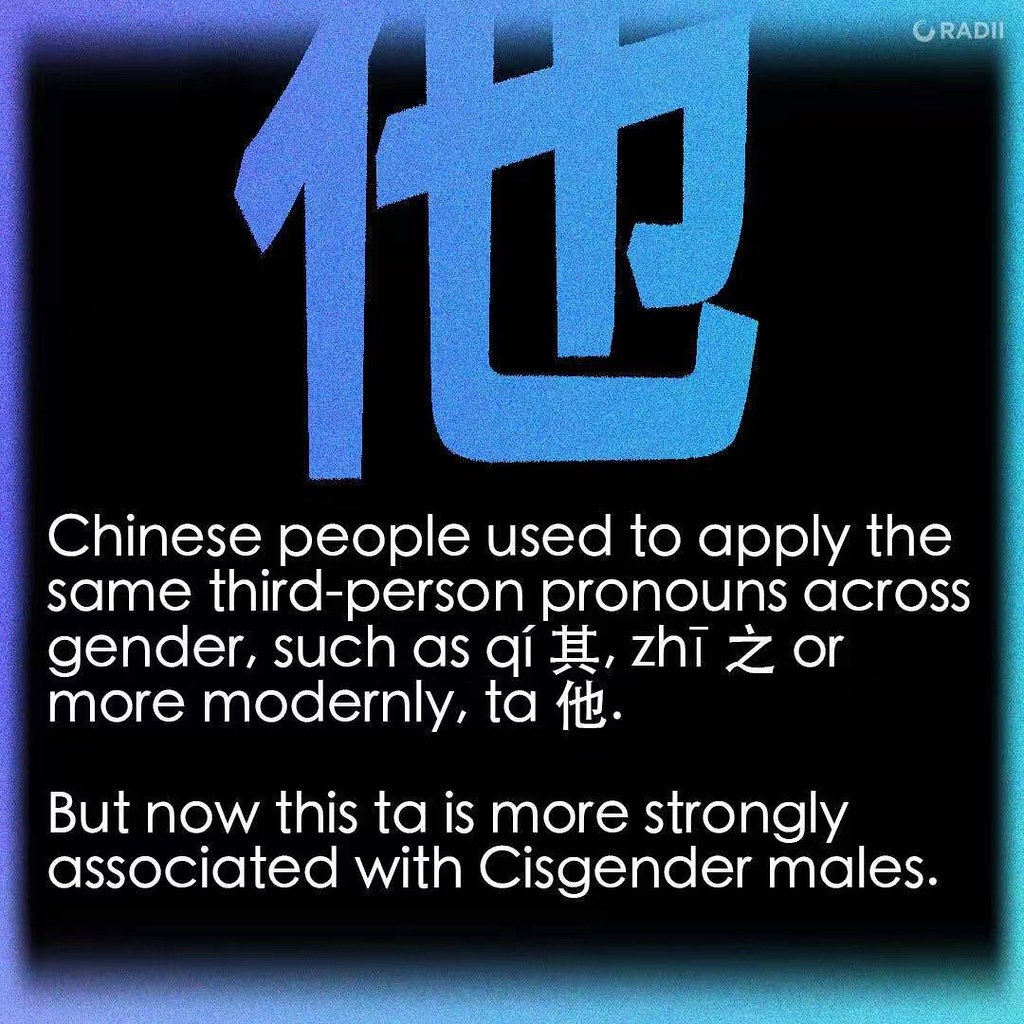

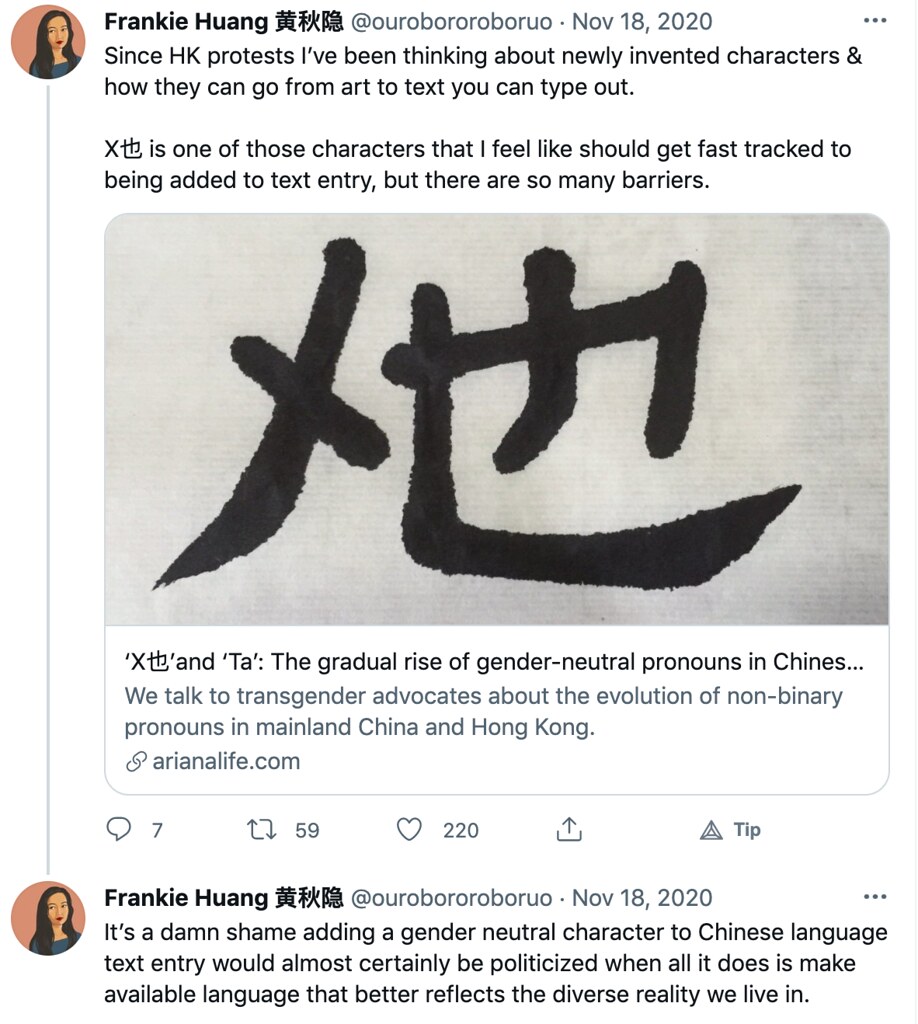

Jul 2021Gender-Neutral Pronoun Options for Chinese Characters

I’m not going to write much here about Chinese pronouns 他 / 她 / TA (all “tā”), because the images below sum everything up nicely. (If you want more detail, be sure to click through to the full article).

Via Radii:

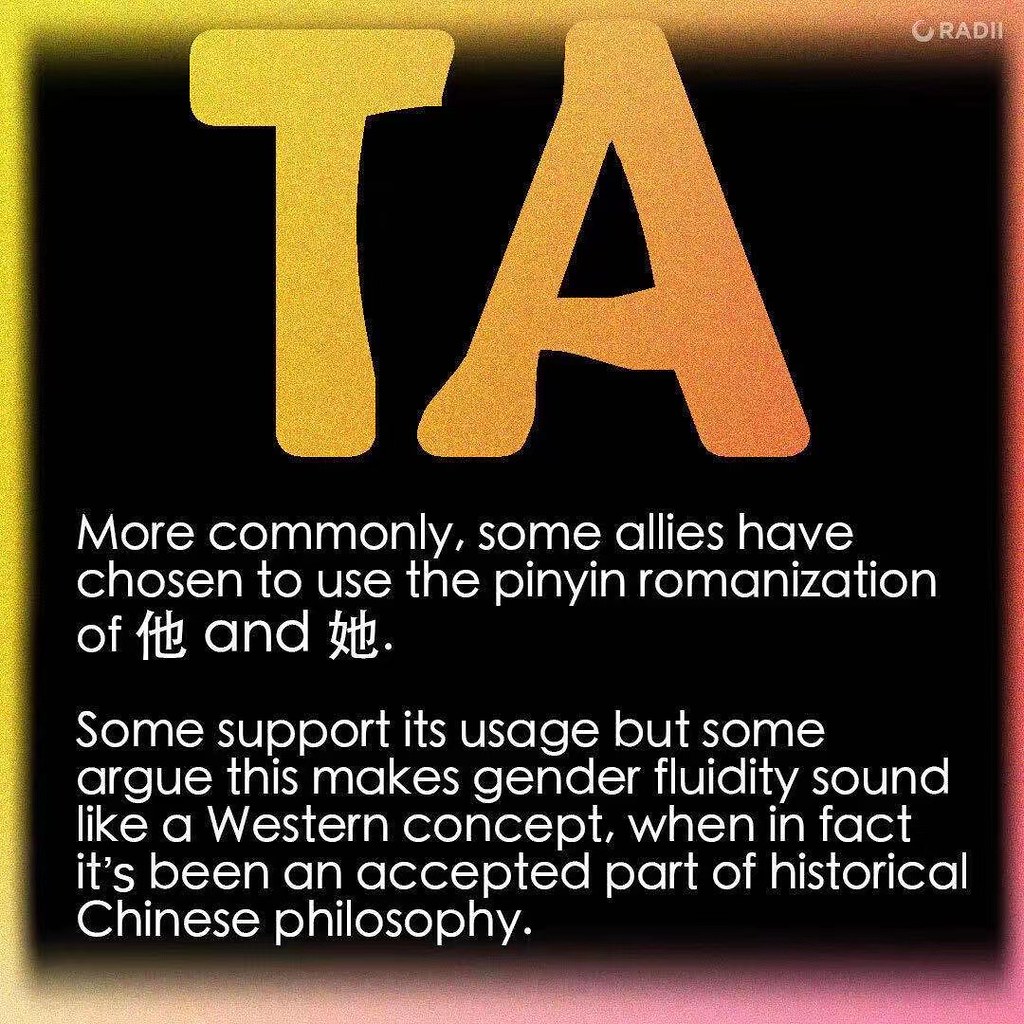

For uses of TA “in the wild,” see this article: TA: Pinyin with a Purpose.

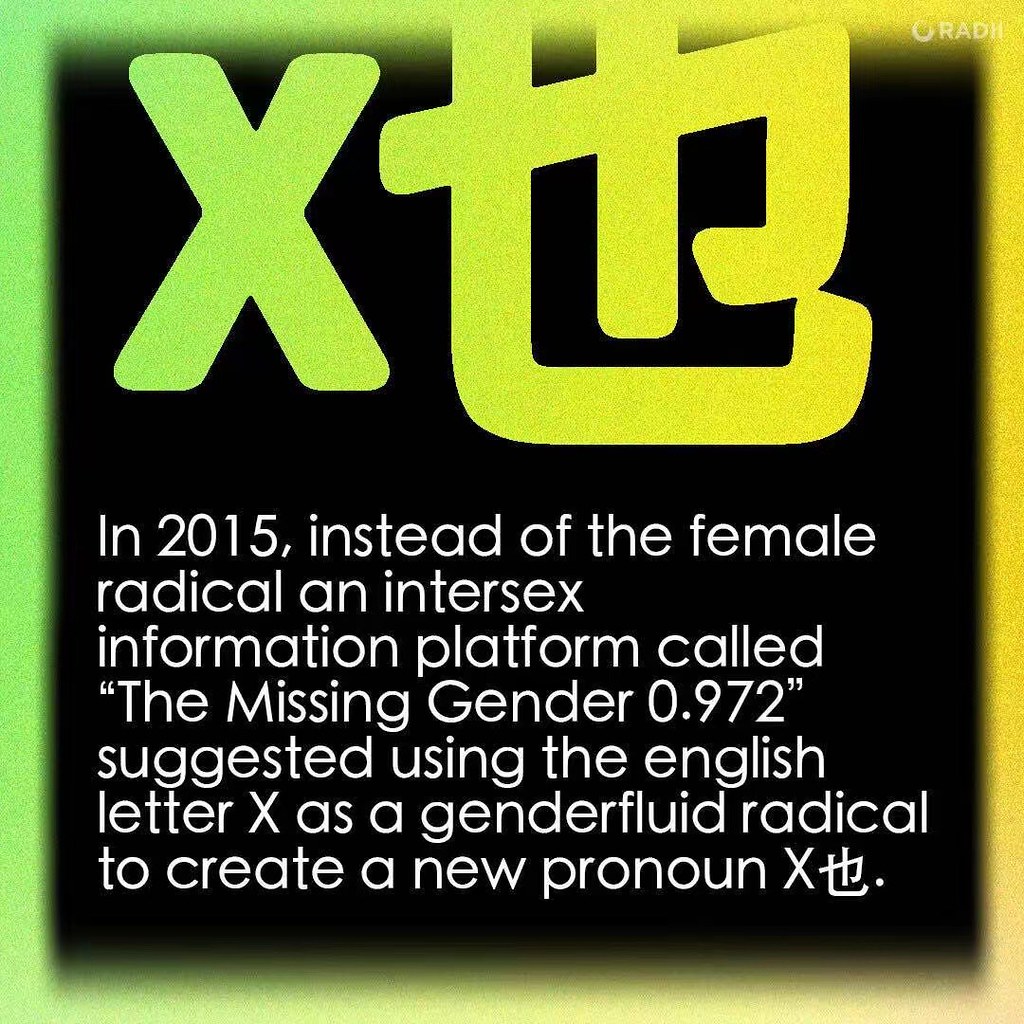

I’m definitely not a fan of inserting the “X” into a Chinese character. It just breaks the natural aesthetic when done with an English X.

There are “more Chinese” ways of doing it, though (via Twitter, also via Radii, via Arianalife):

(So if you ever see the text “X也,” now you know what it refers to.)

Here’s a more creative attempt at a new pronoun character:

The 无 (wú) on the left side, of course, means “none” or “does not have.”

So it seems that we currently have these three gender-neutral Chinese pronoun options, each of which require two characters to type:

- TA (tā)

- X也 (tā)

- 无也 (tā)

Finally, if you’d like to see the “god pronoun” (closely related to these) be sure to check out this article: Respectful Characters.

16

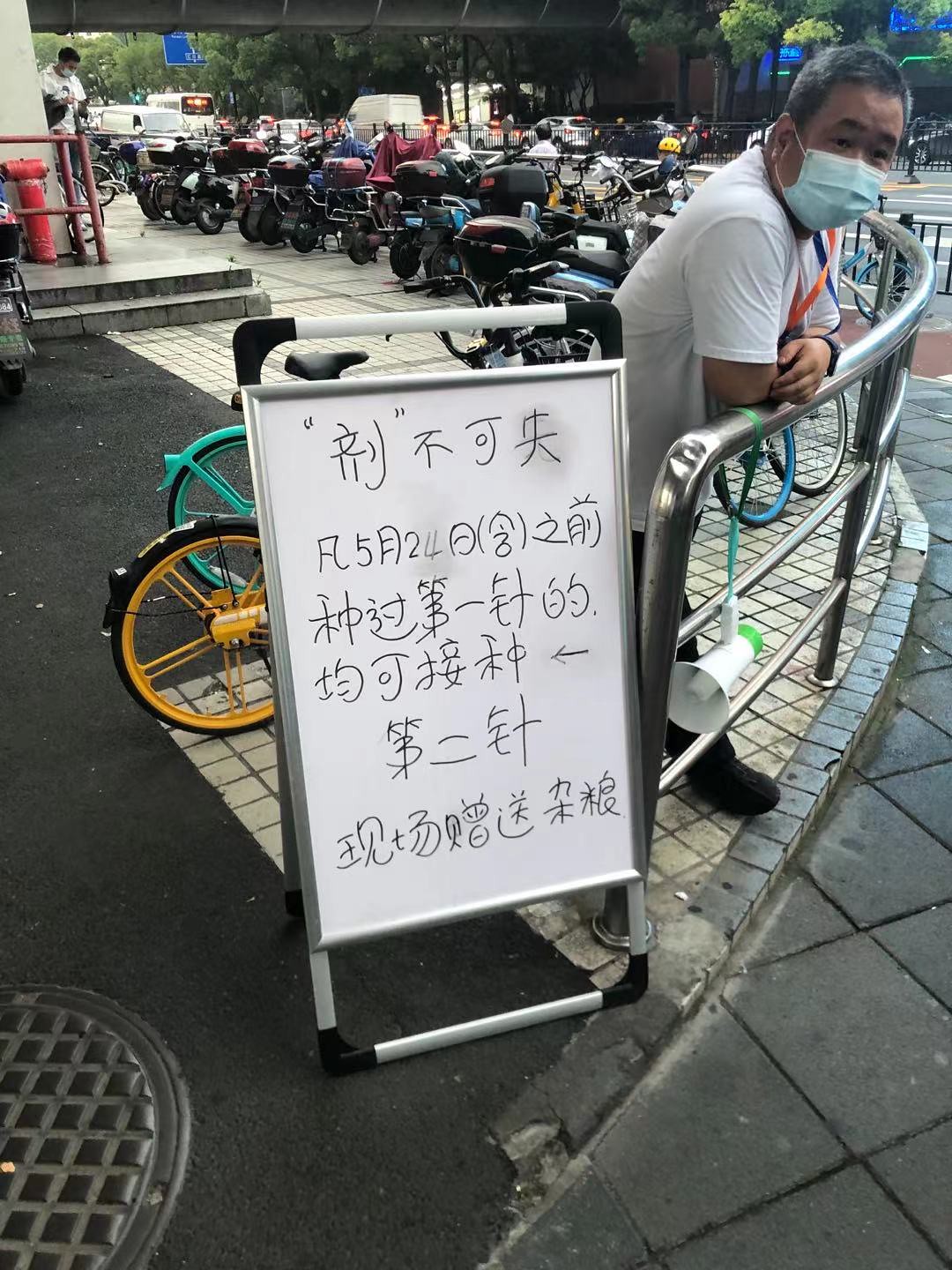

Jun 2021Shanghai Urges Residents to Get Vaccinated… via Megaphone! (audio)

Recently every time I go out on the street, my ears are affronted by recorded audio messages played on loop via megaphone. They’re super annoying, but they’re for a good cause: urging any unvaccinated residents to hurry up and just do it (and also get a prize!).

Over the past few weeks I have recorded the following audio on my phone, so it’s not super high quality, but have a listen if you’re curious (transcripts and translations will follow). This audio is notable because it’s clearly recorded by non-professionals, so some interesting pronunciation issues creep in.

Please note that this stuff is not easy to understand. “Loudspeaker” recordings are among the most difficult to understand in any language, so these are no exception… plus they’re about vaccinations, which is not exactly a softball topic! (Please excuse my rough translations!) AND, on top of everything else, most of them also include a pronunciation curveball or two.

Here we goooo…

打疫苗,送油或酸奶,即到即打。

[Get vaccinated. Free vegetable oil or yogurt. No wait.]

Linguistically, this one is interesting because the guy clearly says “jì dào jì dǎ” (即 pronounced as 4th tone), but the word 即 (which he definitely means) should be pronounced “jí” (2nd tone). It’s one of those “pronunciation variants” (possibly due to the speaker’s regional accent) where although it’s not really standard, native speakers have no trouble understanding.

今天疫苗接种第一针最后一天,欲打从速。

[Today is the last day for your first vaccination shot. Don’t delay.]

We have another “pronunciation variant” here. The speaker pronounces 接种 as “jiēzhǒng”, but it’s officially “jiēzhòng.” (You hear both.)

This one sounds like it’s dropping a chengyu on us, but it’s using a recognizable 4-character phrase as a template: “欲 + [one-character verb] + 从速”. It just means “if you want to [that verb], ASAP.” It’s often used in sales, for “limited time offers.”

打疫苗啦,打疫苗啦!布丁酒店旁有疫苗接种点,现场接种第二针有好礼相送,大家快来接种吧。

[Get your vaccination, get your vaccination! Vaccination location next to the Pudding Hotel. Get a prize on the spot for your second shot. Everyone come get inoculated!]

This time the speaker pronounces 接种 as “jiēzhòng.”

This one is kind of funny to native speakers, because the tone the girl uses sounds like she’s announcing a two-for-one sale at the supermarket, but it’s about vaccinations.

And yes, 布丁酒店 literally means “Pudding Hotel.” It’s the name of the hotel where they’re doing the vaccinations. (Don’t ask me!)

5月24日及之前接种第一针的可以打第二针啦!今天打有赠奖礼品哦,就在前方蓝色大巴。

[Anyone who had their first shot before May 24th can get their second shot! If you get your vaccination today, receive a free gift at the blue bus ahead.]

There’s the same “pronunciation variant” again. The speaker pronounces 接种 as “jiēzhǒng”, but it’s officially “jiēzhòng.” (You hear both.)

Sorry, this one is the hardest to understand, since people around me were talking. And yes, there was a bus there, parked on the sidewalk, full of “gifts.”

If you look in the above two photos, you can find the megaphone.

11

Jun 2021Atlas Shrugged: the Ice Cream Bar

OK, when I saw this “Atlas Shrugged” ice cream bar at a local convenience store, I just had to buy it.

Any mention of Atlas Shrugged always takes me back to freshman year of high school in the IB program. I felt confident in my English abilities at first… until I saw one of my classmates, Ted, reading one of the thickest paperbacks I had ever seen. It was Atlas Shrugged. At this point I had never even heard of Ayn Rand, and had no clue while my fellow 14-year-old classmate would want to read such a book. (I still don’t! Ha…)

But I digress.

The Chinese name is: 阿特拉斯耸耸肩, which is the official title of the translated Chinese novel. (Literally, something like “Atlas gave a shrug.”)

How was it? Ummm… absolutely terrible. Couldn’t finish it. It claims that the flavor is “lemon powder with sea salt,” but it came across more like “fake cheesecake with caramel shell.”

Ayn Rand would not approve. I highly suspect Ted wouldn’t either.

P.S. Yeah, unmistakeable “Junk Food Review” vibes here… I still need to fix up those old pages.

04

Jun 2021Cell Phone Locker (Enterprise Edition)

I saw this in a hair salon here in Shanghai:

The text reads:

手机保管箱 (shǒujī bǎoguǎnxiāng)

Cell Phone Storage Box

The employees at the salon are allowed to use their phones while they’re waiting for a task, but as soon as they’re given one (washing hair, cutting hair, etc.) they have to stick their phones in here for “safe keeping” while they do their work. This is the first time I’ve seen this system in a hair salon.

I know a household or two that could use one of these!