04

Feb 2015My Chinese Classroom vs. Our Chinese Classroom

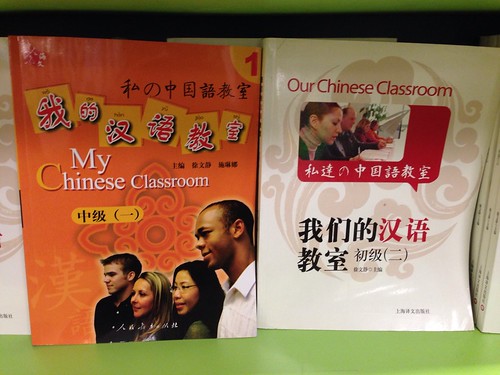

The Chinese textbook My Chinese Classroom has been around since at least 2005; I once reviewed it on this site, in fact. I was amused, then, to see a new textbook, Our Chinese Classroom (《我们的汉语教室》) on the shelf of a local book store, right next to My Chinese Classroom (《我的汉语教室》).

Upon closer inspection, the main editor is the same (徐文静), but the publishers are different.

I’m curious: is this the next generation of the series, with a rather unimaginative title evolution, or is this a new project for a new publisher that blatantly rips off the old one?

I didn’t have time to check this out today, but I will examine later. (If anyone knows the inside scoop, let me know!)

27

Jan 2015Kaiser’s “Dude System” of Tones

Let’s face it, learning the tones of Mandarin Chinese is a challenging endeavor, and the stereotypical “mā má mǎ mà” example isn’t super helpful. Of all the alternate systems to help learners develop a feeling for the tones, my favorite is the “dude system,” originally developed by Kaiser Kuo for The Beijinger. He recently reposted it in Quora, and I’ve gotten his permission to share it here (with a little audio addition of my own):

The Dude System:

1. First Tone: Dūde, the disapproving tone, as to the clumsy roommate who’s just knocked over your three-foot Graphix and gotten bong water all over your Poli Sci 142 reader: “Dude, I can’t believe you spilled my bong again!”

2. Second Tone: Dúde?, in the concerned but creeped-out way you might address the roommate you discover sitting naked and cross-legged in the dark, chanting “Nam-myoho-renge-kyo” and sounding a little brass bell.

3. Third Tone: Duǔde, scornfully, as if your roommate has asked to borrow 50 dollars so his sensei can align his chakras: “Yeah right, dude.”

4. Fourth Tone: Dùde!, as if you are exclaiming in triumph to your roommate when coming home from class having gotten a date with mega-babe Elena from your macroeconomics class.

In case you don’t get it and need to hear it, here’s an MP3 I made: dude1234.mp3. (It adheres more to Kaiser’s descriptions above than to the exact Chinese pronunciation.)

[Originally posted on Quora.]15

Jan 2015Practicing Chinese Tone Changes

Wow, looks like I started off the year with a two-week blogging break! I’m not finished blogging, by any means, but I’ve been busy finishing off AllSet Learning’s new products, dealing with a sick household, and preparing for a new baby (due next week!).

The AllSet Learning Store now has 8 downloadable products, and the latest 3 products are entirely related to tone changes. Tone change rules (referred to in linguistics as “tone sandhi,” or 变调规则 in Chinese pedagogy) are an important concept for learners to master, but you’re never ready for it right after you just learned pinyin and the four tones. Tone change rules need to be addressed sometime in the “elementary” period, and when exactly the learner is ready is going to vary a bit from person to person. You know a learner is ready when she starts truly acquiring individual tones and noticing on her own that what Chinese people say doesn’t always match the tones on the pinyin.

Unfortunately, textbooks tend to force learners to memorize these rules too early, before learners really have a strong concept of the tones in the first place. To give a specific example: New Practical Chinese Reader 1, Lesson 1 covers the sounds of pinyin (pp. 5-6), followed immediately by the four tones (p. 6), followed immediately by “third tone sandhi” (p. 7). Yikes!

Mastering Chinese tones is a long-term endeavor, which starts with learning what the four tones sound like and how to produce them. This foundation is essential before moving on to tone changes. Even after learning all the rules as an elementary learner, it’s going to take quite some time to be able to consistently apply those tone change rules in whole sentences, so most intermediate learners will benefit from more challenging tone change exercises.

With all this in mind, AllSet Learning has created the exercises that learners need at various stages. Our new products are:

– A2 Tone Changes

– B1 Tone Changes

– B1 Tone Changes for Third Tones

Feel free to ask questions about the products. Our versioning system makes it easy to update the products and add features.

I’ll be addressing some of the complexities of tone changes in future posts.

31

Dec 2014“Open” IP in China

An interesting article hit Hacker News the other day, relating to the Chinese model for innovation among hardware startups: From Gongkai to Open Source. The article uses the Chinese words gongkai (公开), meaning “open,” and kaiyuan (开源), meaning “open source.”

Here’s how it starts:

Photo by Ars Electronica on Flickr

> About a year and a half ago, I wrote about a $12 “Gongkai” cell phone… that I stumbled across in the markets of Shenzhen, China. My most striking impression was that Chinese entrepreneurs had relatively unfettered access to cutting-edge technology, enabling start-ups to innovate while bootstrapping. Meanwhile, Western entrepreneurs often find themselves trapped in a spiderweb of IP frameworks, spending more money on lawyers than on tooling. Further investigation taught me that the Chinese have a parallel system of traditions and ethics around sharing IP, which lead me to coin the term “gongkai”. This is deliberately not the Chinese word for “Open Source”, because that word (kaiyuan) refers to openness in a Western-style IP framework, which this not. Gongkai is more a reference to the fact that copyrighted documents, sometimes labeled “confidential” and “proprietary”, are made known to the public and shared overtly, but not necessarily according to the letter of the law. However, this copying isn’t a one-way flow of value, as it would be in the case of copied movies or music. Rather, these documents are the knowledge base needed to build a phone using the copyright owner’s chips, and as such, this sharing of documents helps to promote the sales of their chips. There is ultimately, if you will, a quid-pro-quo between the copyright holders and the copiers.

> This fuzzy, gray relationship between companies and entrepreneurs is just one manifestation of a much broader cultural gap between the East and the West. The West has a “broadcast” view of IP and ownership: good ideas and innovation are credited to a clearly specified set of authors or inventors, and society pays them a royalty for their initiative and good works. China has a “network” view of IP and ownership: the far-sight necessary to create good ideas and innovations is attained by standing on the shoulders of others, and as such there is a network of people who trade these ideas as favors among each other. In a system with such a loose attitude toward IP, sharing with the network is necessary as tomorrow it could be your friend standing on your shoulders, and you’ll be looking to them for favors. This is unlike the West, where rule of law enables IP to be amassed over a long period of time, creating impenetrable monopoly positions. It’s good for the guys on top, but tough for the upstarts.

Very interesting stuff. Read the whole article on bunniestudios.com.

29

Dec 2014Kaiser on North Korea and China

Kaiser Kuo answered a question on the relationship between China and Korea which included an analogy that was too good to pass up (I love a good analogy):

Question:

> What impression does the average Chinese person have of North Korea?

> Is it similar to the rest of the world or do they have a different view considering the relation of their government with North Korea?

Photo by ~~Yuna~~ on Flickr

Kaiser’s Answer:

> I’m not sure about the “average” Chinese person, but nearly all the Chinese people I know feel a range of emotions toward North Korea that would include embarrassment, shame, pity, contempt, and outright hostility. It’s like a nasty dog that was already a family pet long before you were born: once upon a time, it wasn’t so crazy and bitey, and actually helped scare off would-be burglars and you were even kind of proud of what a tough little sonofabitch he was. Now he’s always barking, straining at the leash, trying to bite the neighbors (and ruining your relations with them), shitting all over the place, and costing you too much to feed.

See the question for the full answer (all two paragraphs of it).

Update: Kaiser’s response on Twitter:

@sinosplice Ha! Glad you liked that. A couple more containing extended metaphors: http://t.co/woPOZGs10t and http://t.co/2zey7vePwI

— Kaiser Kuo (@KaiserKuo) December 29, 2014

23

Dec 2014Shallow Deep

Apparently 浅深 (literally, “shallow deep”) is a bathhouse in Shanghai. I’ve only ever seen it from the outside; I just like the design of the sign.

Light posting these days as I’m down with a bad cold and Christmas sneaks up on me!

12

Dec 2014“Double 12”: China’s Cyber Monday

Today is December 12, AKA 双十二, literally, “double twelve” in Chinese. It’s a day when Taobao (淘宝) and JD.com (京东) offer huge discounts online (and this year, Taobao is really pushing its AliPay mobile phone payments, sort of similar to Apple Pay, but using barcodes on users’ phone screens instead of NFC). So today is kind of like China’s Cyber Monday.

12-12 is clearly riffing on 双十一 (“double eleven”), a modern Chinese holiday that was once known as “Singles Day” (光棍节) but has since been largely co-opted by online retailers and remolded as China’s Black Friday.

At first I was kind of amazed that this 12-12 holiday even “took.” It’s just such blatant commercialism to follow up a 11-11 shopping holiday with a 12-12 shopping holiday. But so far, as long as the discounts keep coming, no one seems to mind. What’s next, co-opting 1-1 (元旦节)? I have to say, 双一 certainly doesn’t have the same ring to it.

Some screenshots for today’s sales from the aforementioned sites:

I’m not buying anything. I’m having my own little Buy Nothing Day. (不消费日 in Chinese, but make no mistake: this is not a familiar concept in China, and people find it pretty ridiculous.)

09

Dec 20149 Polite Phrases for the Subway

The following photo was snapped in a subway. It’s a public service announcement (or “propaganda poster,” if you prefer) that reminds passengers to be polite. I thought it was kind of interesting to take note of what expressions were chosen to illustrate politeness.

Here are the words, with pinyin and English translations, and a few observations of my own:

-

请: please

This clearly polite word is nevertheless just a little awkward for foreigners trying to speak polite Chinese, because it’s not nearly as ubiquitous as “please” is in English.

-

没关系: it doesn’t matter

The nice response to “I’m sorry.”

-

同志: comrade

This word is a bit old-fashioned. It’s also modern slang for a gay person.

-

您请坐: please sit

您 is the polite form of 你, plus you have the 请 in there. You might say this if you were being super polite to an elderly passenger while giving up your seat. (您 is also more common in northern China.)

-

谢谢: thank you

Can’t go wrong with “thank you!”

-

您好: hello

您 is the polite form of 你, so this is the politer form of 你好. (It also poses a translation problem… Maybe you come close if you use “hi” for 你好 and “hello” for 您好? The difference is still bigger in Chinese, though.) The expression 您好 also reminds me of customer service reps.

-

不客气: you’re welcome

Literally, “don’t be polite.”

-

再见: goodbye

I never really thought of this as polite, exactly, but I guess it’s better than taking leave without a word?

-

对不起: I’m sorry

Of course.

05

Dec 2014Is This Pun Illegal?

This pun:

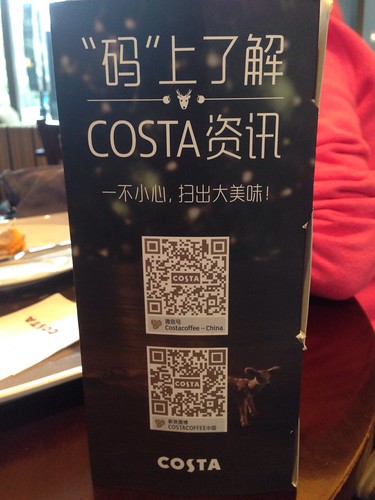

The punny text reads:

> “码”上了解

[punning on 马上, “right away,” using the character 码, which refers to “code,” in this case, the QR code]

It’s been widely reported that Beijing is banning wordplay in attempt at pun control. This seems ridiculous, especially considering the Chinese penchant for giving the reader zero credit, and always putting the punned character in quotations marks (see above example).

David Moser’s quote on the issue:

> It could just be a small group of people, or even one person, who are conservative, humorless, priggish and arbitrarily purist, so that everyone has to fall in line. But I wonder if this is not a preemptive move, an excuse to crack down for supposed ‘linguistic purity reasons’ on the cute language people use to crack jokes about the leadership or policies. It sounds too convenient.

I’ll be watching to see if punning in advertising stops…

03

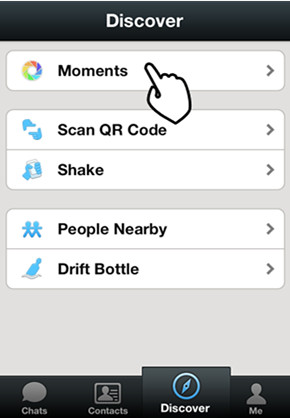

Dec 2014The Appeal of WeChat’s Moments

Dan Grover recently posted an in-depth overview of Chinese Mobile App UI Trends. Here’s an excerpt that talks about WeChat’s “Moments” that I especially liked:

> When I first saw it, it seemed as if someone hastily duct-taped an ersatz Facebook news feed to the app and slapped the Picassa icon on it. But as I’ve used it, I’ve found it a surprisingly original and subversive feature. In fact, it’s everything Facebook’s news feed isn’t:

> No filtering — Every one of your friends’ posts is here, with no filtering or re-ordering. If one of your friends is annoying, you can take them off the feed, but it’s an all-or-nothing deal.

> More intimate — When you like or comment on a friend’s post, only they and any mutual friends can see it – not all of both parties’ friends, as on Facebook. This means that only the author of a post has an accurate idea how many people liked or commented on their post. This lowers’ users inhibitions in engaging with their friends’ posts.

> No companies/news — When you follow a company or news site’s official account, they push their updates in a separate area, not on your news feed. Though a friend can re-post content from these accounts to Moments, it takes some deliberate action.

> No auto-posts — Third-party apps can post to Moments, but only if the user initiates it, gets switched into WeChat, and manually confirms the post, each time.

> No games — Tencent makes boatloads of money off of Zynga-style social media games. However, they’ve had the good sense to relegate this activity to a “Game Center” section of the app that can be safely ignored.

> No photo filters – Though many types of content can be posted to Moments, it’s biased towards photos. Moments also actively eschews Instagram-style filters, in an attempt to make posts fast, spontaneous, and raw.

> As a result of these design decisions, and the way it’s sewn into the parent app, people here are addicted to checking this feed, more than any other. To switch between messaging to checking the feed, to commenting and engaging, and back is a swift and fluid movement that people perform countless times each day.

There’s a lot more in the full article. Check it out.

25

Nov 2014Better Non-comprehension: Getting Beyond “ting bu dong”

A while back I was having a conversation with my friend Ben about the challenges he faced learning Chinese. He said that one of the problems was that whenever he didn’t understand even part of something that was said, the whole conversation would shut down pretty fast. I asked him for some more details on these types of encounters, and pretty quickly it came out that he was using the phrase 听不懂 (tīng bù dǒng, “I don’t understand”) exclusively, anytime he had trouble following what was said.

Big problem! While 听不懂 is a useful phrase that any beginner needs to learn, it can’t help in all situations. In short, Ben’s strategies for communication were long overdue for an upgrade. His Chinese was good enough to go beyond just 听不懂; he really needed to start communicating his non-comprehension better. What he was communicating with that 听不懂 was essentially, “I don’t understand anything you are saying,” when in fact it was only part of what was said that gave him trouble.

There’s a solution to this problem. It involves better communication on the part of the listener. When you don’t understand, you can communicate what you don’t understand better. Because sometimes the person talking is drunk, or old, or young, or suffering from a speech impediment, or mumbling, or even drugged! None of that is your fault (one would hope), but you do have to deal with it.

Here are some options for when you’re ready to go beyond 听不懂:

- 什么?我没听清楚。What? I didn’t hear clearly.

This one is good partly because it’s not the over-used 听不懂, which immediately clues the listener into the fact that you may, in fact, know more Chinese than just a handful of phrases from a phrasebook. Also, claiming that you didn’t hear clearly (whether true or not) kind of implies that if you had heard clearly, you may have understood. Give yourself a little credit. People frequently don’t speak clearly.

我没明白你的意思。 I didn’t understand what you mean.

Don’t be fooled; this is not the same as 听不懂. This sentence may be used by native speakers when they understood every word, but the sentence doesn’t make sense to them or the speaker’s meaning is unclear. So this one is perfect for those situations when you understood every word but don’t know what the person means. This is a really good one to add to your repertoire.- 你在说谁? Who are you talking about?

This one only makes sense if you’re reasonably sure the person is talking about somebody, but you’re not clear who. Obviously, this can really backfire if they weren’t talking about any person, but most things people say involve some person, so there’s a little room for error here.

- 你的意思是……So you mean…

Sometimes your best bet is to just guess what the person means. Don’t underestimate the usefulness of this strategy! I’ve seen beginners with 5% comprehension totally guess what a speaker means (and then articulate it in super basic Chinese), while an intermediate learner stands next to them with 60% comprehension, dumbfounded. The difference is paying attention to context. One of the advantages of guessing the speaker’s meaning (even when you don’t guess right) is that you’re kind of “showing your cards.” You’re giving the person an idea of your vocabulary and listening comprehension level. And sometimes the words you use are enough to help them modify what they said originally into a form you can understand.

There are a lot of others you could use too, and probably all of them are better than 听不懂. You just have to put yourself out there a little. Don’t shut people out with your non-comprehension. They’ll help you if you let them.

Update: Fiona Tian has created a useful video based on this blog post:

13

Nov 2014Zhongwen Extension for Chrome: Now with Grammar Links

I’ve been recommending the Zhongwen extension for Chrome for years already, and it’s also the one we recommend to users of the Chinese Grammar Wiki. Well, with the most recent update to the extension, that recommendation has gotten a lot stronger! The Zhongwen extension now makes it easy to look up words on the Chinese Grammar Wiki by keyword. For example, if you’re using the Zhongwen extension and mouse over “都,” you’ll notice that it has a grammar keyword entry. Press “G” to open that in a new tab, and you’ve got a list of all the grammar points on the wiki that use 都. Pretty useful!

While working with the extension developer, Christian Schiller, to add this new feature to Zhongwen, I also took the opportunity to do a short interview with him:

11

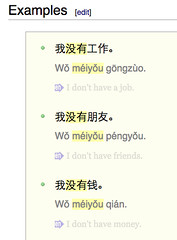

Nov 2014The Chinese Grammar Wiki: now with tons of Pinyin

The Chinese Grammar Wiki has been steadily growing over the years. In its early days, when tons of articles were “stubs,” and lots of grammar points still needed appropriate example sentences, we decided not to include pinyin for those sentences, and instead outsource that work to browser plugins. We recognized that once the page contents stabilized eventually, it would definitely be better to add both English translations and pinyin for all sentences, or at least the sentences at the lower levels.

Well, that time has come! All A1 (Beginner) and A2 (Elementary) grammar points on the Chinese Grammar Wiki now have both English translations and pinyin. Thanks to our tech team and volunteers for slowly but surely making this happen. The Chinese Grammar Wiki is now way more accessible to beginners as a result.

Oh, it also has lots more colorful images now! Not exactly vital to the learning experience, but not bad either.

If you’re learning Chinese and haven’t checked out the Chinese Grammar Wiki recently, please pay it another visit. If you like it, please help spread the word!

04

Nov 2014Cooking Your Way to Vocabulary

Brendan O’Kane writes on Quora in answer to the question, “What should I do in order to improve my Chinese vocabulary?“:

[…] Cooking shows are an absolutely awesome resource for studying any language, because:

They’re pretty focused in terms of spoken content. Sure, you get hosts who yammer on about how their grandmother used to make such-and-such a dish for holidays or whatever, but when you get right down to it, the core content — “this is a thing; this is how you make the thing” — is pretty predictable. Most of the discussion involves objects that are onscreen — usually being handled or pointed at — and actions that are being performed for you. If your hypothetical host says “把整头大蒜掰开,用刀切去根部的硬结,放入碗中倒入清水,” you don’t even have to know all of the words: he’ll be picking up the 大蒜 and 掰开’ing it right in front of you, then 切去’ing the 硬结 at the 根部 using his 刀, etc. At the end of it you’ll know how to cook a dish.

I like this idea, but I must admit I’ve never done it. There are a lot of highly-specific action verbs that might take years to master if you just learn them as you come across them, but cooking shows are one way to get exposed to a high number of them in a relatively short period of time.

Anyone out there tried this for Chinese? What are the good Chinese cooking shows?

28

Oct 2014Boaz’s Chinese Kids

Scrolling through Boaz Rottem’s China Flickr photos, I was struck by these great pictures of happy Chinese children. Enjoy!

See also: BoazImages.

21

Oct 2014Spartacus = Super Taka?

Here’s a restaurant on Fuzhou Road (福州路) in Shanghai:

So the Chinese name is 斯巴达克斯牛排, which includes a straightforward transliteration of the name “Spartacus,” which you can easily find on Baidu Baike and on Chinese Wikipedia, plus the word for “steak.” But somehow the English name of this restaurant is “Super Taka Steak.”

How does that work? I’d love to hear theories.

15

Oct 2014Chinese Teachers: Use Your Chinese Names!

Chinese teachers, please have your students call you by a Chinese name. You’re not helping them by calling yourself some easier-to-pronounce English name. I would have thought that this was obvious, but after all these years in the business, I can now see that it is not obvious to many otherwise well-meaning teachers. So I’ll spell it out here. (Please forward this to your Chinese teacher who doesn’t ask you to use a Chinese name in your interactions.)

So why should students of Chinese call their Chinese teachers of Chinese by a Chinese name? I’m glad you asked…

Using your actual Chinese name shows respect for the culture

My dad is one of those people that enjoys befriending recent immigrants in the United States. He likes to find out where they’re from, why they came to the U.S., etc. One of the things he always asks “Bob from Iran” or “Alice from China” or whoever is, “what’s your real name?” He does this not only out of curiosity, but also to show a genuine respect for their culture and interest in their identity. Most of the time immigrants are thankful for this gesture (even if he can’t always accurately reproduce the sounds that make up their names).

As a teacher, you get to decide how your students address you. But in Chinese culture, it’s a non-question; teachers are simply called “[Surname] Laoshi” by their students. As a teacher of Chinese, why would you not use this opportunity to start teaching your students about Chinese culture in an easy, practical way? Get the cultural respect going from lesson one. Students will be totally on board.

Using Chinese names is good practice

One of the main arguments for NOT using real Chinese names is that “my Chinese surname is too hard for foreigners.” OK, maybe your surname is hard for most foreigners, but your students have decided to learn Chinese. They probably already know it’s not easy. Even if your surname is particularly difficult to pronounce, it’s probably only one syllable. And it’s one syllable your students are going to be able to repeat over and over every lesson, and they’re eventually going to start getting it right.

So don’t baby them. Let them struggle a little bit. It doesn’t matter if your surname is “Xu” or “Zhu” or “Jiang” or “Zhang” or “Yu.” They’ll get it eventually.

It’s a vote of confidence

So it’s a pretty safe bet that your students will not be pronouncing “Xu” correctly on day 1, and that’s OK. But when you tell them, “You don’t need to try to say ‘Xu.’ Just call me Vivian,” you’re casting a vote of no-confidence in their ability to learn correct pronunciation. That’s a terrible thing for a teacher to do.

Not only are you saying, “you can’t learn this,” but you’re also saying, “you can’t learn this, and I won’t even be able to teach you.” So it’s also a vote of no-confidence in yourself as a teacher!

Cast a vote of confidence in your students by telling them, “my name is a little tricky to pronounce, but don’t worry; you’ll get it eventually. Just keep trying.”

Have confidence in them from the first lesson, and they will keep trying. They need you to believe that they can learn to correctly pronounce your name.

Chinese names are hard to remember

This is totally true. Chinese names are hard for foreigners to remember. But you know what doesn’t help? Enabling learners to never even try to remember, and always copping out by using English names. That’s just lazy.

Chinese names are hard to remember in the beginning. But learners get better at it by learning more real Chinese names, and the process starts with you, the Chinese teacher. With each new Chinese person the learner meets, he learns a real Chinese name, and one by one, the names start to seem less insane. They become manageable.

Start your students down this road.

But what about Hong Kong?

One thing I’ve heard over the years is, “but in Hong Kong, Chinese people often use English names. It’s also a Chinese thing.” OK, yes, that’s true. But as a learner, I really don’t need help learning names like “Jacky” and “Coco.” What I need is more practice with the less familiar names… the ones starting with “Zhang” and “Wang” and “Hu.”

So Hong Kong-style English names are easy freebies that we sometimes get, but they’re certainly not the norm for everyone in mainland China, and they’re not an excuse to avoid Chinese names altogether.

Don’t be absurd

Lastly, let me leave you a counter-example. Imagine a blond-haired blue-eyed foreigner living in China and working as an English teacher. We’ll call him “Carl.” He teaches English, but he also knows Chinese, and uses it a little bit with beginners.

But here’s the thing: Carl has chosen “Zhang” (张) as his Chinese surname, and in his English classes he has all of his students call him Zhang Laoshi (张老师). It’s because “Carl” is hard to pronounce, and he just finds it easier.

Is that not absurd? Would the Chinese students not find this odd? Does it help the students to call Carl “Zhang Laoshi” in English class?

Chinese teachers, please have your students call you by a Chinese name. They’ll thank you later.

中文翻译:中文老师:请用你的中文名!

See also:

– Sinosplice Guide to Chinese Pronunciation

– AllSet Learning Pronunciation Packs

09

Oct 2014Analysis Paralysis in Chinese Studies

You’ve probably heard of analysis paralysis, but where does it come into Chinese studies? Studying a language is fairly straightforward, right? I’m referring not to being overly analytical about grammar, but rather about vocabulary. How can one be overly analytical about vocabulary? This is something that technology has made easy in recent years.

Most of my AllSet Learning clients use Pleco or Anki to review vocabulary. Both have built-in SRS flashcard functionality, so doing occasional reviews pretty much solves that problem, right? Well, maybe… SRS drawbacks aside, certain personality types like to take a more active role in the vocabulary categorization process. Yes, categorization. That’s the trap.

You see, when you save a word to your flashcard system, you can also categorize it. Where did this vocabulary come from? What type of vocabulary is it? How high priority is it? You can go as deep down this rabbit hole as you want. And you can spend a lot more time organizing and re-organizing your flashcards than actually reviewing them.

So typically when a client comes to me with “flashcard organization problems,” the way forward is pretty clear: it’s time for some serious vocab axing. The situation can be as bad as physical packrat (or even hoarder) tendencies, except with vocabulary data instead of old newspapers or whatever. In most cases, the learner is much better off chucking the majority of this carefully collected information. Usually the most exquisitely categorized lexical items are the least useful. Reducing everything to one “high priority” list is the way to go. This really is all you need, and you get back all that time you used to waste endlessly organizing words (without actually learning them).

For those that are seriously attached to their accumulated lexical data, technology offers a solution: you can back it up! Back up the data, dump it somewhere, and keep your active word list as simple, focused, and clutter-free as possible. (Chances are you’ll never go looking for that backup.)

If this problem sounds vaguely familiar, you may be thinking of the bookshelf problem. It’s amazing, isn’t it, how we humans can be motivated to do something related to learning a language, but actually pour the majority of our efforts into useless activities? The worst, part, of course, is that even a meticulously curated collection of lists which are somehow regularly reviewed don’t guarantee any kind of conversational ability. But then actually talking to people is a bit too random for the analytical brain to handle.

The solution is simple, though: less organizing, more talking. A more bare-bones vocabulary list will help you move in that direction. If you’re a vocabulary hoarder, I strongly urge you to reconsider your approach.

03

Oct 2014Improbable Wifi

I’d love to see a list of the most improbable places that have wifi in China. I had lunch at this little hole in the wall the other day, and snapped these pictures:

Unfortunately I didn’t notice the wifi until I was on the way out. I do wonder how good the wifi was.

30

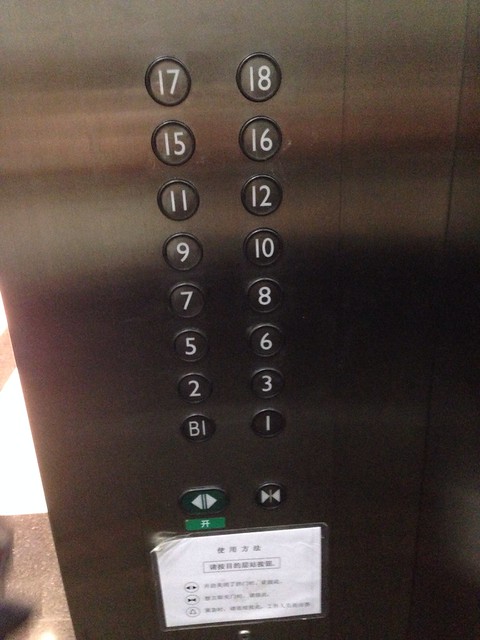

Sep 2014Missing Elevator Buttons

I recently read China Simplified’s book, Language Gymnastics. It’s a great entertaining introduction to the Chinese language which combines Chinese and foreign perspectives. The book included this passage in chapter 4, which is aptly titled “Sorry, There Is No Chapter Four“:

> Enter a Hong Kong residential tower elevator and you’ll often discover buttons for floors labeled 3A, 12A and 15B–no doubt alternative universes guarded by daemons and fairies. Other times the 1st floor is renamed the “ground floor” (following British conventions) and the 2nd floor is counted as the 1st floor, so then the 3rd becomes the 2nd and abracadabra! — the dreaded 4th floor becomes the less deadly 3rd floor right before our very eyes. Problem solved.

> Whenever a lift whizzes past the imaginary gaps between the 3rd and 5th floors or the double gap between the 12th and 15th floors, I’m taken by cleverness of it all. A property agent can show her clients a breathtaking flat on the “16th floor” without admitting it’s only 13 floors up. Sweet–higher rent and nobody dies. So depending on your perspective, apartment 4D at 1441 West 14th Street is either a deathtrap or the bargain of a lifetime. I say drop that cash and grab that key.

Chinese number superstitions are real, and not just in Hong Kong. I happened to encounter this elevator in Shanghai:

Yeah, quite a few numbers missing there. In this case, skipping so many floors also means that the penthouse becomes “18,” a number desirable for the “8.”